Longfellow Field: The Park that Bombs Bought

If any park in Minneapolis should be a “memorial” park, perhaps it should be Longfellow Field, because it was bought and built with war profits. It would be hard to explain it any other way. The neighborhood around present-day Longfellow Field is one of the few in the city that didn’t pay assessments to acquire and develop a neighborhood park. That’s because the park board paid for it with profits from WWI.

The story begins with the first Longfellow Field at East 28th St. between Minnehaha Avenue and 26th Avenue South. (There’s a Cub Store there now.) It was once one of the most popular playing fields in the city—and it is the largest playground the park board has ever sold.

The park board purchased the field in the upper right of this photo in 1911 and named it Longfellow Field. This photo, looking northwest, was taken from the top of Longfellow School at Lake St. and Minnehaha Ave. shortly before the land was purchased for a park. Minnehaha runs through the center of the photo and ends at E. 28th St. where the vast yards of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway begin. Minneapolis Steel and Machinery is on the left or west side of Minnehaha. (Charles Hibbard, Minnesota Historical Society)

The origins of that field as a Minneapolis park go back to 1910 when the park board’s first recreation director, Clifford Booth, recommended in his annual report that the city needed a playground somewhere between Riverside Park and Powderhorn Park.

Clifford Booth, shown here in 1910, was the first recreation director for Minneapolis parks and an unsung hero in park history.

It was the only addition he recommended to the playground sites he already supervised around the city.

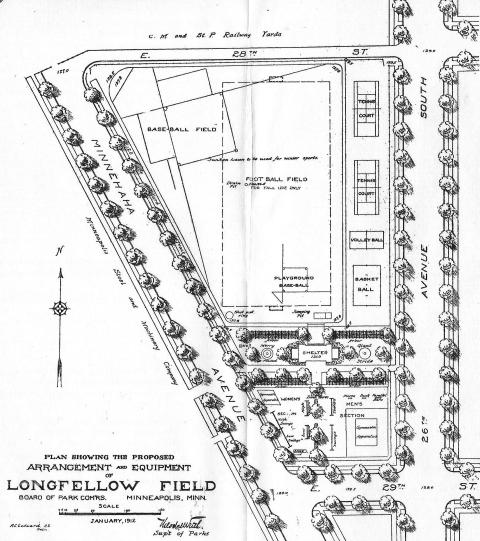

The following year, the park board found the perfect place within the area Booth suggested: an empty field just off Lake Street, about equidistant from Powderhorn and Riverside, a stones throw from Longfellow School, easily accessible by street car, and it was already used as a playing field. The park board purchased the 4-acre field in 1911 for just over $7,000 and spent another $8,000 to install football and baseball fields, tennis, volleyball and basketball courts, and playground equipment.

An architect was hired to create plans for a small shelter at the south end of the park, but when bids for the shelter came in at more than $10,000, double what park superintendent Theodore Wirth had estimated, the park board decided it couldn’t afford the shelter.

This plan for the development of Longfellow Field was published in the 1911 Annual Report of the park board. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

Despite the absence of a shelter, Wirth wrote in 1912 that Longfellow was one of the most active playfields in the city. Longfellow Field and North Commons were the venues for city football and baseball games for two years while the fields at The Parade were re-graded and seeded. The popularity of the field was attested to by the police report in the 1913 annual report of the park board, which claimed that additional police presence was necessary to control the crowds at football games at Longfellow Field and North Commons.

This Is Where the Intrigue Begins

I was surprised when I learned that the park board sold the park in 1917. The park board had never sold a park before. Why then—after 34 years of managing parks? And why this park? The park board’s explanation in the 1917 annual report was pretty weak, stating only that the field “became unavailable for a playground on account of the growth of manufacturing business in the vicinity.” The property was already on the edge of an industrial zone—see photo above—when it was purchased, so this was no revelation.

Longfellow School, on Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue, was built in 1886 and used until 1918. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The park board resolution on October 17, 1917 to sell the land provided a bit more explanation, but it still seemed less than forthcoming. It wasn’t just the growth of manufacturing business, the resolution claimed, it was also the school board’s decision to close Longfellow School and build a new school farther south. Moreover, the park board claimed that to make the playground useful it would be necessary to invest in improvements and a shelter. Given the other shortcomings of the site, the park board didn’t think it prudent to make those investments at that site.

So the park board declared that the site was no longer useful for a park, a legal requirement to get district court permission to sell the land, and it was sold for $35,000 to the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company.

At the time the park board decided to sell the field it also expressed its intention to find a “more suitable area” for a park and playground nearby in south Minneapolis. Less than two weeks after the sale was announced, the board designated land for a second Longfellow Field, the present park by that name, about a mile southeast in a much less populated neighborhood. The park board paid the $16,000 for the new land—not just four acres, but eight—and for initial improvements to the park from the proceeds of the earlier sale. It was a boon for property owners in the vicinity of the new Longfellow Field: a new park without property assessments to pay for it. The owners of three houses that had just been built across the street from the park must have been thrilled.

When I learned all of this a few years ago, I assumed that in the end the land deal was about the money—the opportunity to sell for $35,000 land the board had bought only six years earlier for $7,000. Even if you subtract the $8,000 spent on improvements, that was a nice return. And to keep that sum in context, remember that the park board shelved plans for a park shelter when bids exceeded estimates by $5,000. Thirty-five grand was a lot of money for a cash-strapped park board.

But the deal still puzzled me, especially because of the unusual way the transaction was introduced in park board records.

Park board proceedings, October 9, 1917, Petitions and Communications:

“From the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company —

Asking the Board to name a price at which it would sell the property included in the tract of park lands known as Longfellow Field.”

Talk about asking to be gouged! Who starts negotiations that way? Name a price? That seemed fishy. So did the speed of the deal. Two committees were asked to report back on the issue the following week, the first indication that someone was in a big hurry to get a deal done. The joint committees not only reported back a week later, they had come up with a price, $35,000, and had essentially concluded the deal. There hadn’t been time for much dickering over the number; the park board had a very motivated buyer. Moreover the board selected land to replace Longfellow Field only two weeks later. As decisive as early park leaders often were, this was unprecedented speed. Too much money. Too fast. Too little explanation.

Perhaps too little deduction on my part as well, but that’s where the matter stood for me the last few years until I decided recently to look into it a bit more as I was compiling a list of “lost parks” in Minneapolis. What I learned is that the decision to sell Longfellow Field had less to do with demographic shifts or manufacturing concentration in south Minneapolis than what was happening in the fields of France and the waters of the North Atlantic.

The United States Joins a World at War

For more than two years, the United States had stayed out of the Great War that embroiled much of the rest of the world. But in early 1917 Germany took the risk that a return to unrestricted submarine warfare and a blockade of Great Britain, including attacks on American ships, could bring about an end to the war before the United States could mobilize its army and economy to have a significant impact on the ground war in Europe. Germany knew that its actions would bring the U.S. into the war—and they did. The U.S. Congress declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917—and began to mobilize in earnest. Part of that mobilization was the enactment of the selective service, or draft, law in May 1917 to build an army. Another part was the procurement of weapons and equipment needed to fight a war.

Of course the manufacturing capacity for war couldn’t be built from scratch. Existing expertise, process and capacity had to be converted to war products. That meant beating plowshares into swords.

That’s where Minneapolis Steel and Machinery came in. In the fifteen years since its founding, Minneapolis Steel had become one of the leading suppliers of structural steel for bridges and buildings in the northwest. That was the “steel” part of the name. The “machinery” was represented most famously by Twin City tractors, but also by engines and parts it manufactured for other companies.

Doesn’t the logo for a line of products from the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company remind you of the logo of our favorite boys of summer? (Thanks to Tony Thompson at twincitytractors.tripod.com)

All I knew about Minneapolis Steel and Machinery was that in the 1920s it was one of the companies that merged to become Minneapolis-Moline and that it was notoriously anti-union. I didn’t know that it was an important military supplier, too.

The first evidence I found of the company’s production for war was a November 10, 1915 article in the Minneapolis Tribune that claimed the company would begin shipping machined six-inch artillery shell casings to Great Britain by January 1, 1916. The paper reported that the initial contract, expected to be only a trial order, was for almost $1.5 million.

Less than two weeks later, another Tribune report made it clear that the company’s involvement in the war was much broader. The paper reported on November 23 an order from Great Britain for 100 tractors from Bull Tractor, another Minneapolis company, for which Minneapolis Steel did the manufacturing and assembly. The tractors, still a relatively new invention, would be shipped from Great Britain to France and Russia to supplant farm horses drafted for war service or already killed in the war. Minneapolis Steel was also shipping 50 steam shovels to be used to dig trenches on the Russian front. Both orders were placed by the London distributor for both Minneapolis Steel and Machinery and Bull Tractor.

Shell orders must have continued for Minneapolis Steel and Machinery after the initial order in 1915, too, because on August 16, 1917 the Tribune reported a new order for the company. Under the headline, “Steel and Machinery Plant to Be Enlarged to Meet Uncle Sam’s Demand for Shells,” the paper reported,

“War orders just taken will necessitate a considerable enlargement of the buildings of the Minneapolis Steel & Machinery company. The company, after completing its shell contract with the British government last spring, decided not to accept any more shell orders, but the United States insisted and a large contract is the result.”

Artillery played an unprecedented role in a war in which both sides were dug into trenches. Blanket bombardments preceded most offensive actions. The result was a French countryside that resembled nothing earthly.

The report, which quoted Minneapolis Steel vice president George Gillette, continued that the company was also manufacturing steam hoists for ships and expected more contracts as the building program progressed. More contracts, unsolicited according to Gillette, did indeed materialize in the next month for carriages for 105 millimeter guns and steering engines for battleships. Those contracts reportedly required a doubling of the company’s manufacturing capacity. At that time government contracts accounted for 75 percent of the company’s output. By early 1918, the Tribune reported that Minneapolis Steel and Machinery had already been awarded $23 million in government contracts.

In the midst of this rash of new military contracts, Minneapolis Steel asked the park board to name its price for Longfellow Field. Even before the district court finished its hearings on the park board’s proposed sale, the company had obtained building permits for three new warehouses, two of them in the 2800 block of Minnehaha Ave., a short foul pop-up from home plate at the former Longfellow Field.

A Civic Duty

The spirit of the times suggests that while money may have been a factor in the park board’s prompt action, it likely was not the primary motivation for selling Longfellow Field. The park board probably viewed the sale as its civic and patriotic duty to assist the war effort—especially given the other valid reasons for moving the playground.

An example of the patriotic fervor generated by the war—to which park commissioners could not have been immune—was a dinner held at the Minneapolis Club, June 12, 1917, to raise funds for the American Red Cross, which was preparing field hospitals to treat wounded soldiers. (Did the army not have a medical or hospital corps?) The next morning the Tribune reported that in one hour the 200 business and civic leaders at the dinner pledged more than $360,000 to the Red Cross. That amount eclipsed the city’s previous one-evening fund-raising record of $336,000 for the building fund for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts a few years earlier.

The report is noteworthy especially for the accounts of the number of men present, among the wealthiest and most influential citizens of Minneapolis, who had sons and nephews on their way to France—so different from the wars of the last four decades.

“Almost every man who rose to name his contribution had a son already in France or on his way. So often did the donor, in making his contribution, add that his boy was wearing the khaki of the army or navy blue that Mr. Partridge (the emcee of the evening) called the roll to ascertain just how many present had sons or nephews in the service. Including two who announced that they themselves were entering the service, the total was 56—mostly sons.”

One of the two men present who was entering military service himself was introduced as Dr. Todd, son-in-law of J. L. Record, who was president of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery. Record pledged $10,000 to the Red Cross on behalf of his company that night.

Ernest G. Wold was one of two WWI pilots from Minneapolis who died in the air over France. The other was Cyrus Chamberlain. (Minnesota Historical Society)

Among others who pledged money were two bankers who had sons in the military aviation services, F. A. Chamberlain, chairman of First and Security National Bank, and Theodore Wold, governor of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank. Both men—and Chamberlain’s wife—were leaders in raising funds for the Red Cross and in selling Liberty Bonds. Their sons never came home. Ernest Wold and Cyrus Chamberlain died in the air over France in 1918. They were jointly honored by having Minneapolis’s airport named Wold-Chamberlain Field, a name that still stands. This was several years before the Minneapolis park board assumed control of building and operating the airport.

The Park Board During the War

Also making pledges at the Minneapolis Club dinner were park commissioners William H. Bovey and David P. Jones. Two other park commissioners who took active roles in the war effort were Leo Harris who resigned from his seat on the park board to enlist and Phelps Wyman who took a leave of absence from the park board to serve as a landscape architect for a group designing new towns for the workers needed at military factories and shipyards.

But it was the president of the park board in 1917 who had the most to lose—or prove—during those days of heated anti-German rhetoric. Francis Gross was the president of the German-American Bank in north Minneapolis. Gross had worked his way up from messenger to the presidency of the bank, which was said to be the largest “non-centrally located” bank in Minneapolis. The bank, founded in 1886, had been located on the corner of Plymouth Avenue and Washington Avenue North since 1905. Gross eventually served 33 years as a park commissioner between 1910 and 1949, earned the nickname “Mr. Park Board,” and had a Minneapolis golf course named for him. He must have been indefatigable, because his name pops up in association with many civic and financial endeavors.

Of all the park commissioners in Minneapolis history, Frank Gross is one of the most intriguing to me. If I could find some cache of lost journals of any of the city’s park commissioners since Charles Loring and William Folwell, I would most want to find those of Frank Gross. He’d be a great interview subject.

In the second year of the war, before the U. S. entry into the conflict, Gross was quoted in the Tribune expressing his view that Germany’s desire for peace was “sincere.” He urged the U. S. and other neutrals to push for peace. “I have no sympathy with the assertion that one side must be victor,” he said. “There can be a fair settlement now on nationality lines.”

Gross’s role in the war effort changed considerably after the U.S. entered the war. The tension of war in the U.S. was underscored when in March 1918, the German-American Bank officially changed its name to North American Bank. Gross asserted that the old name no longer represented the bank’s business or clients, adding “it is not good or desirable that the name of a foreign nationality be attached to an American institution.” In announcing the name change, Gross emphasized that his bank had been the first Minnesota bank to join the federal reserve system in 1915 “to do its part to establish a national banking system in our country so strong and efficient that it could meet any demand our country might make upon it.” (Tribune, March 8, 1918.) Gross’s implicit message: those demands could even include making war on the fatherland of the bank’s founders.

Only three weeks after Gross’s bank changed its name, he went on a speaking tour of towns outside Minneapolis that had large populations of German immigrants or descendants. The Tribune described his visit to Waconia on March 28, 1918. “In line with the belief of the state war savings and Liberty Loan committees that there is a distinct desire in German communities to have the war explained by persons of German birth or descent, Frank A. Gross, president of the North American bank, has spoken to several meetings composed entirely of Germans in the last few days,” the Tribune’s report began. Gross told of how he had circulated among the estimated crowd of 300 people of German descent, mostly farmers, before he spoke and found a “feeling that anyone of German birth or German descent is not wanted as a citizen of this country.”

He ascribed the feeling to the manner in which “overzealous orators” had attacked the German people, “not distinguishing between German imperialism, against which we are making war, and the German people.” Gross said that he then told the people of Waconia they “certainly were wanted as American citizens, but that the citizenship carried with it the responsibility of 100 per cent loyalty to this nation.” Gross said he also dispelled the notion that this was a “rich man’s war,” asking if they thought the “rich would send their boys to war just so their fathers could make a little more money.”

Family experience: My father, who grew up in a small town in rural Minnesota, recounts that his older brother and sister, born before WWI, spoke primarily German before they went to school, but my father and another sister, born after WWI, were never taught German.

Gross later was a prominent speaker at meetings promoting the purchase of Liberty bonds, especially in predominantly German communities such as New Ulm, Hutchinson and Glencoe, and he spoke at “Americanization” meetings—scheduled in Minneapolis neighborhoods with large “foreign elements” according to the Tribune—about “Patriotism.” He shared the podium at one such meeting in north Minneapolis with Rabbi S. M. Deinard whose subject was “The Obligation of the New Generation to the Old” and Mr. E. Avin of the Talmud Torah who gave a patriotic address in Yiddish. Gross also became an instructor, along with future Minneapolis mayor Wallace Nye, at a school for Minneapolis draftees before they were sent off to military camps.

The park board’s annual reports written while Gross was president of the board in 1917 and 1918 reveal very little of the impact of war on parks other than brief references to the heavy burden of taxes and contributions to welfare organizations and the lack of funds for park maintenance. From Gross’s other activities, however, as well as those of other park commissioners, it is apparent that the board would have had a strong sense of patriotic obligation to do what it could to assist the war effort. And that certainly extended to providing expansion space for one of Minneapolis’s largest military suppliers. So the original Longfellow Field became a casualty of war—and the neighborhood surrounding the new Longfellow Field acquired a park without having to pay property assessments.

The Last Link

One connection remains between the descendants of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery and Minneapolis parks. Minneapolis Steel and Machinery built Bull tractors, but the engines were supplied by another local company, the Toro Motor Company. Bull, Toro, get it? One contemporary newspaper account (November 17, 1918), describes Toro as a subsidiary of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery, but the website of The Toro Company today does not claim that connection. (The Toro website does claim the company produced steam steering engines for ships during WWI, however, a product that newspaper reports in 1917 attributed to Minneapolis Steel and Machinery.) Regardless of legal relationship, the two companies were closely connected and Toro is the sole survivor of the Bull, Minneapolis Steel, and Toro tractor trio.

Toro later focused its efforts on lawn-care products, famously lawn mowers, and still specializes in turf management products mostly for parks, athletic fields and golf courses. Each year in recent times, Toro and its employees, along with the Minnesota Twins Community Fund, have donated the materials, expertise and labor to rehabilitate or upgrade a baseball field in a Minneapolis park. These little gems of ball parks now exist in several Minneapolis parks, from Stewart Park to Creekview Park. Thank you, Toro. I don’t know specific park board needs now, but wouldn’t it be appropriate if Toro helped put in a fabulous field at Longfellow Park in honor of the connection long ago?

I’ll leave the final word on WWI in Minneapolis to a preacher.

“I rejoice that I am no longer needed as a partner in the grim business of killing.”

— Rev. Elmer H. Johnson, pastor of Morningside Congregational church who had worked for 11 months at the artillery shell factory of Minneapolis Steel to augment his church salary. (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, December 22, 1918)

David C. Smith

NOTE: Bob Wolff of The Toro Company provides additional details on that company in a “Comment” on the David C. Smith page. (May 31, 2012). In a separate note, Bob said he’d also look into finding photos of the first Toro turf management products used in Minneapolis parks. Stay tuned.

© David C. Smith

[…] 1914 map as a park—Longfellow Field—was a few years later absorbed into the industrial area, an interesting story in itself. All of that gave way to parking lots, big-box stores, and other sprawling structures in the waning […]

[…] also re-published the story of how today’s Longfellow Field , the second property with that name, was created when the first Longfellow Field was sold to a […]

Beautifully written piece, David. Thank you for your well researched and interesting blog, it’s very appreciated.

Thank you, Julieann. I’m glad you enjoy it.

[…] April, in an article about the original Longfellow Field and its sale to a munitions maker during WWI, I […]

[…] Off to War. Wirth wrote in the 1917 annual report that the depletion of the engineering force had made some park work impossible. Four of fifteen employees in the engineering department had entered active military service that year and four others had left for other employment. Even engineer A. C. Godward had volunteered for national service, Wirth wrote, and if he was accepted, he would request a leave of absence. The following year, after the U.S. finally entered the war, and more of the engineering staff enlisted, Wirth wrote that Godward was supervising surveying and map reading courses at the University of Minnesota for Students Army Training Camp leaving the park engineering staff with only one man, a junior draftsman. Wirth also wrote, not coincidentally, that the park board spent less on park improvements in 1918 — about $73,000 — than in any year since 1907. No wonder the 1918 annual report presented only three park plans, by far the fewest of Wirth’s 30-year tenure, except at the depth of the Great Depression. The lack of other projects and plans, and the engineering staff to create and execute them, may also explain Wirth’s focus on the river banks above the falls that year. He had many fewer demands on his time than he was accustomed to. Two park commissioners — Leo Harris and Phelps Wyman — also served their country during WWI. More of their story is told here. […]

[…] 1917 for $35,000. That’s only the beginning of the story. Read the rest and see more photos here. The playground at the first, “lost” Longfellow Field in 1912. (Minneapolis Collection, […]

[…] Bob Wolff from Toro provided three great old photos of Toro products at work in Minneapolis parks. (See previous stories here and here.) […]

[…] one day I might find a use for it. Well I already wrote the post I should have put it in — Longfellow Field – about the connection between Minneapolis Steel and Machinery and Toro and mentioned […]

[…] during World War I in a recent post have pointed to another factor that may have reinforced the willingness of the park board to sell the first Longfellow Field to Minneapolis Steel and Machinery as the company expanded to fulfill military contracts: Theodore […]

Surprising and interestng, as usual David. Thanks!

Thanks for reading, Andrea. Glad you liked it.