“The Yard” — or Downtown East Commons: A Caution from Minneapolis Park History

Hurrying to create a park in “The Yard” (since renamed the “Commons”) between downtown and the new Vikings stadium could result in disaster, if the history of Minneapolis parks provides any lessons. The greatest land-use mistakes in Minneapolis park history came from creating parks for purposes other than the relaxation, recreation, entertainment or edification of its citizens. Creating grounds for a pleasant stroll to a stadium eight days a year isn’t reason enough to make “The Yard” work as a park. Planning for those two blocks has to go well beyond landscaping only for the benefit of surrounding property owners, too.

An Expensive Failure: The Gateway

On four notable occasions, the park board has created parks largely for other than “park” reasons. The first, and still most-disastrous, was the creation of The Gateway in 1913 at the junction of Hennepin and Nicollet Avenues just west of old Bridge Square approaching the Hennepin Avenue Bridge. The triangular park was created to be an attractive “gateway” from the railroad station into downtown. The welcome intended for visitors, or travellers returning home, was clear from the words carved in stone on the pavilion at The Gateway:

“More than her arms, the city opens its heart to you.”

That slogan must have sounded less smarmy to 1913 ears than it does to mine. Parks, as well as slogans perhaps, were still on experimental footing in the “new” cities of the American west and The Gateway was the first venture of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners into downtown Minneapolis.

The buildings razed to make room for the park reportedly housed 27 saloons, which for many park advocates was reason enough to create the park. But neither open heart nor closed saloons were enough to make the park successful.

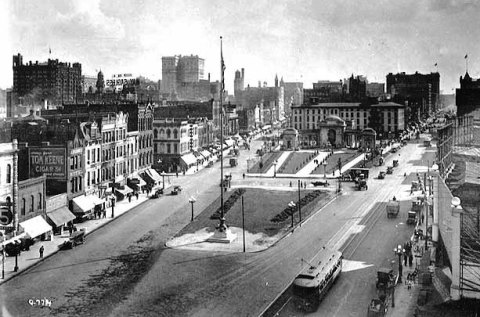

The Gateway 1918 at the intersection of Nicollet Avenue (left) and Hennepin Avenue (right). The Mississippi River and Hennepin Avenue Bridge are behind the photographer, Charles P. Gibson. (Minnesota Historical Society)

By 1923, the park board was spending more than 5% of its annual citywide operating budget on the park, mostly on park police patrols, because, in addition to the city’s arms, the park board had opened toilets – er, “comfort stations” – in The Gateway’s pavilion. The park quickly became a favorite hangout for lumbermen between jobs, as well as the unemployed, indigent or inebriated. What was supposed to get rid of ugliness and beautify the city, became an eyesore itself.

This infamous 1937 photo may overstate the case, but it does suggest one typical use of the park. Notice however that there are no nappers across the street, on the block that holds the pavilion and fountain. (Minneapolis Star Journal, Minnesota Historical Society)

Despite an attractive pavilion and a fountain donated by Edmund Phelps (now in Lyndale Park near the Rose Garden), the park served too few constituents (or at least some the city thought undesirable) and little park purpose beyond decoration. The park was controversial even when it was built, with such thoughtful park observers as former park commissioners William Folwell and Charles Loring opposing the park. Loring’s wife owned some property condemned for the park, but nonetheless he predicted correctly that it would become a home for indigent men. (See Florence Barton Loring’s reflective response here.) The pavilion was closed and leveled in 1953 and the fountain was removed to Lyndale Park in 1963, when the old Gateway ceased to exist. (For the rest of The Gateway story go here, then click on “Parks, Lakes, Trails…”, then “Gateway” in the index.)

Fenced. Desolate. Doomed. The Gateway in July 1954 after demolition of the pavilion, looking toward the river from Washington Avenue. (Minneapolis Star Journal Tribune, Minnesota Historical Society)

The Gateway was by far the most expensive park built during the first thirty years of the Minneapolis park board’s existence. The total cost was nearly one million dollars, more than had been paid to acquire Lake Harriet, Lake Calhoun and Lake of the Isles – plus parks and parkways along both sides of the Mississippi River – combined!

A Huge Success: Wold-Chamberlain Field

The next time the park board was asked to build something for the city turned out quite differently. When Minneapolis needed an airport, the park board was the only municipal entity that could legally own land outside city limits. Therefore, it fell to the park board in 1928 to own and operate the municipal airport on the site of the old motor speedway next to the Fort Snelling military reservation. The park board operated and developed Wold-Chamberlain Field, built it into a respectable airport, and turned it over in the mid-1940s to the newly created Metropolitan Airport Commission. Chalk one up to collaboration among city, park, civic and business interests. The goals, however, were clear, unambiguous and limited – and in the 1920s the airplane was still little more than a curiosity. Few people anticipated the future importance of flying machines and places to land them.

Wold-Chamberlain Field, Minneapolis’s airport, 1941. The passenger terminal is lower right. Owned and developed by the Minneapolis park board, 1926-1943. One of the only success stories when the park board was asked to develop something other than a “park.” (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

A Second Downtown Disaster: Pioneer Square

The next effort at collaboration was much less successful. Like The Gateway, it was downtown. Another cautionary tale. The U.S. government wanted to build a new post office in downtown Minneapolis in 1932, but asked that a proper setting be provided for the building on the west bank of the river just above St. Anthony Falls – a stone’s throw from The Gateway, which was already admittedly a failure as a park. In the grip of Depression, however, the city needed the jobs and the federal money that would be spent, despite what seem to have been the obvious warnings of The Gateway experience.

Dedication of Pioneer Statue in Pioneer Square in front of the post office, 1936. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

The city asked the park board to build a post office park, but the park board demurred until the city agreed to finance most of the land acquisition instead of having the park board assess property owners. Enough money was left after land acquisition, demolition and improvement to commission a sculpture for the park, which depicted pioneers. Despite the sculpture (now in B.F. Nelson Park) and the attraction of a new, immense post office, Pioneer Square soon followed the path of The Gateway. According to Charles Doell, park superintendent in the 1950s, after the snow melted at the end of the winter of 1953, maintenance crews picked up 70 bushel baskets of empty wine and whiskey bottles from The Gateway. One Monday morning in the summer of 1953, crews picked up 62 empty wine and whiskey bottles from the grass at Pioneers Square. (Charles E. Doell Papers, Hennepin History Museum). Further proof that you can’t just plop green space down in a city and expect it to serve some vague “beautifying” or “park” purpose – even with some dressing up. Pioneer Square also fell to urban renewal in the 1960s. (Read more about Pioneer Square and other “lost” Minneapolis parks here.)

A Drainage Ditch

The fourth instance of the park board acquiring a park for non-park reasons occurred in the far north of the city. The low land around Shingle Creek north of Webber Park often flooded, so was unusable for development. Due to a critical housing shortage for returning soldiers and sailors and their new families after World War II, the city asked the park board to acquire Shingle Creek – from Webber Park to the northern city limit — and lower the creek bed to drain the neighborhood so homes could be built there. The park board very reluctantly complied with the city’s request, even though the park board had higher priorities elsewhere. The effort succeeded in creating new housing lots, but has contributed little to the overall park experience in the city. Creekview Park is certainly a positive in the neighborhood despite its location only a few blocks from Bohannon Park, but Shingle Creek, in places, still resembles what you’d expect of County Ditch Thirteen. (I think Shingle Creek could and should be made a more valuable park resource.)

The Yard. Somewhat off topic, history suggests the advisability of a different name than “The Yard.” It’s kinda folksy and cute, but Minneapolis has twice tried “The (Something)” and both were trouble. (Try writing about them or describing them and you’ll see.) The Gateway and The Parade, both official names, were inevitably shortened to Gateway and Parade. Those two words were distinctive enough to stand alone without creating confusion, at times, but “Yard” isn’t. Whose Yard? Not to mention connotations of prison and the Hennepin County Jail overlooking it. The name may have served Vikings or Wells Fargo or Ryan or Rybak’s marketing efforts, I don’t know its origin, making the place sound homey, as if it was “our” space, personal space, but it has severe limitations for daily usage.

Of these four cases of park building for non-park reasons, the two parks created downtown, The Gateway and Pioneer Square, stand out as dismal and expensive failures. They were built strictly to provide a more attractive setting for other activities and buildings. I’m afraid that is all that the Downtown East Park or “The Yard” is now. And if that is where the discussion remains, it will fail as a park and become an eyesore, a headache or both. Who will go there, why will they go there, what will they do there? What use will be made of the space, what traditions will be shaped there, what memories will be recorded there? If the answer doesn’t involve more than eight Sundays a year, it is the wrong answer. And this is not Chicago, New York, Palo Alto or Cambridge, Mass. It is Minneapolis, which already has parks, lakes, river, streams – and history. Don’t give us someone else’s park and expect it to work.

David C. Smith

© 2014, David C. Smith

[…] The Commons. When I wrote about this donation of public land to the Minnesota Vikings — the park is reserved for private use about 20% of the time at essentially no cost — it was called The Yard. A short time after my post, the name was changed to The Commons. That makes me feel so much better about our city’s largesse to a private business to which we had already donated hundreds of millions. Oh, I almost forgot, we got the Super Bowl for it — with lots of events we couldn’t get into. So much fun. […]

[…] emerging debacle of The Yard prominent in the press (Strib and blogosphere), it is natural to overlook the fact that downtown Minneapolis just opened a brand new public […]

[…] emerging debacle of The Yard prominent in the press (Strib and blogosphere), it is natural to overlook the fact that downtown Minneapolis just opened a brand new public […]

[…] Here is the link to his article: www:https://minneapolisparkhistory.com/2014/07/06/the-yard-or-downtown-east-park-a-caution-from-minneapol… […]

[…] the rest here. News from […]

[…] planners create parks to go with a new Vikings stadium, the Minneapolis Park History blog looks at why some parks became community hubs and others earned bad reputations. (Thanks, […]

[…] planners create parks to go with a new Vikings stadium, the Minneapolis Park History blog looks at why some parks became community hubs and others earned bad reputations. (Thanks, […]

[…] planners create parks to go with a new Vikings stadium, the Minneapolis Park History blog looks at why some parks became community hubs and others earned bad reputations. (Thanks, […]

Thanks for another thoughtful and timely post David. History can be interesting AND relevant!

I’m afraid “The Yard” is unlikely to be a “park” as we commonly understand it or as Horace Cleveland or Charles Loring would have understood the term. Instead, the Yard looks to be shaping up as another of many recent examples of the blurring of public and private spaces that actually delivers predominantly public funding for mostly private benefit. It’s a new model!

What makes Minneapolis’s park system the envy of the world is that it was, for the most part, not developed with this cynical “public-private partnership” transactional approach. The lakes, the riverfront parks, the neighborhood parks were truly developed for the public. Private benefactors and boosters were mostly at arms length or further.

The MPRB is still doing this kind of publicly-spirited park acquisition and development, the Above the Falls parks along the Mississippi River in North and Northeast Minneapolis being the examples that first come to mind. That’s where I’d put my resources and try to leave a legacy if I were a city leader today.

I think you’re right, Whitney. I don’t see many Charles Lorings (and his wives Emily Crossman, then Florence Barton), Thomas Lowrys, Charles Reeves, Clinton Morrisons, or William and Caroline Kings stepping into the breech today. And it seems there are many people with far greater resources in Minneapolis today than even those people enjoyed in their time. I’m sure they had flaws, but I believe that they were motivated in great measure, at least as far as parks were concerned, by a sense of the public good.

I appreciate your comments on the River parks, too. Speaking of the river, this afternoon I visited for the first time the new monument at Sheridan Memorial Park overlooking the river. (Just upriver from Broadway in Northeast.) I was pleasantly surprised. I’ll write more of that visit very soon. I’d encourage everyone to visit and let us know what you think. I should add, in light of my comment above, that the memorial is built on land that was donated to the park board a few years ago by the Puzak family. It is a cherished gift in a grand tradition.

David, I know you’re writing from the parks perspective and this is an interesting slice of history, but I wonder if it’s too limiting to look at “the relaxation, recreation, entertainment or edification of its citizens” only through the parks (and therefore park board land) lens.

The city had a severe problem in the Gateway district that would have persisted there even if they’d built playgrounds, a band shell and ball fields. It failed to address the problem of out-of-work men returning to the city and collecting where the bars and rooming houses served them. The open space served them as well, but it’s not entirely a fault of the park.

We have a lot more examples of ill-advised plazas and parks intended as public spaces. Hennepin County’s parking lot roof, for example. Peavey Plaza, as a programmed public space. The drumlin landscaping outside the judicial building. You could argue that Victory Memorial Drive was a park without a recreational purpose, too, yet it seems pretty successful to me. Also the terraced “park” outside the prior Federal Reserve Building on Nicollet.

Then there’s “The Interchange,” with parklike pretensions.

I agree problems tend to arise when a special-purpose land use tries to masquerade as something for “the people.”

Hi Charlie. I appreciate your comments. The Gateway was never intended to address housing, employment or alchohol abuse problems. Nor is The Yard. In my view, parks can’t solve those problems. In this case, my position is that there are limits on what parks can do effectively and we have to exercise some care in what we expect of them. Calling The Yard a park and expecting it to help transform downtown, with all the limitations placed on it, may be unrealistic, or at least more difficult than it appears, just as we learned from The Gateway and Pioneer Square, and, as you point out, Peavey Plaza. We have to consider how people will use a space — and that has often been in different ways than was expected.

I disagree, however, on Victory Memorial Drive. Perhaps my definition of recreation is broader. The parkway system in Minneapolis, as envisaged by H.W.S. Cleveland, William Folwell and others, was an integral element of “recreation.” Tranquility, serenity, nature. In “longitudinal parks” that were within reach of more people than a single large park would be. Only about the time that The Gateway was conceived, did “recreation” begin to include ball games or almost any other activity that involved sweating.

One outcome of us paying for a new football stadium is that the city is acquiring two blocks of downtown land — with conditions. I think we should exercise some care in ensuring that those blocks of land contribute to rather than detract from the quality of life in Minneapolis. The park is being pitched as one benefit to the city of the stadium deal, and it is now up to us, through the park board, to ensure that it is, regardless of our views of the stadium itself.

That effort should not detract us from trying to solve other problems that “parks” alone cannot. I wanted the Wilfs to pay for their own stadium. Now, I want The Yard, or whatever it becomes, to be a benefit to the city.

My comment on Victory Memorial wasn’t clear. I do regard it and the other longitudinal parks as a success, but it could be argued (by a nonhistorian, anyway) that the stretch laid out there had a different primary purpose from other less grand parts of the Grand Rounds, as a memorial to the war dead.

I’m in sync with your main points. I intended to add that even well-designed parks can fail for reasons beyond their control. The Gateway may or may not have been fundamentally flawed as a park, but it never stood a chance to prove otherwise when the city didn’t adequately address the surrounding social ills.

Perhaps I’m just a harsher critic of park planners! A park plan that doesn’t take into account who will use a park, why they will use it, and how they will use it is fundamentally flawed in my view. Theodore Wirth, who designed The Gateway, had no conception of the park that neighborhood needed. If he had, he might have added a picnic shelter as a gathering or eating place protected from rain and snow, more benches for people to relax on, maybe even nap on, and more shade trees for protection from the elements, in addition to some statement of welcome to visitors. I’m riffing here. A play area of some kind for children may have been not only beneficial for children but may have tempered some of the deleterious behaviors of the transient element of the population. (In Wirth’s defense, he proposed acquiring much of nearby Nicollet Island as a park, which might have served that population more effectively.) The Gateway did end up symbolizing the city’s failures to address some social and economic problems, but I maintain that it was a standalone failure as a park, too.

I didn’t understand your reference to Victory Memorial Drive in that context, although I’ll try to think of a more appropriate example, because a parkway along the city’s western border in north Minneapolis had been imagined for 30 years by the time WWI came along and construction of the parkway was underway several years — moving north from Theodore Wirth Park, then Glenwood Park — before plans for the final section were converted to a memorial to fallen soldiers after the war.

This discussion is all timely for me and I hope the subject attracts more comments. I’m working on a novel in which a developer proposes privatizing a public park that has been languishing and used by the homeless, so maybe I’m looking too closely through the social lens!

I look forward to seeing that, Charlie — and I know well and respect greatly your passion for the subject. Please keep us posted on your progress and when we might expect a public reading.

Fascinating perspective. Thank you.

Thanks, John. It think this presents an interesting urban planning challenge as we wrestle with contemporary park management and financing realities, magnified in this case by our complex relationships with professional sports franchises. It is a true test of public-private collaboration and may help establish case studies, positive or negative, for the future. There are smart people on all sides of the issue whose talent for creative compromise and innovation will get a trial by fire. I hope all of them, public and private, recognize the full range of possibilities and dangers.

Bravo! David, for this timely post on the creation of “parks” for other purposes than recreational parks as Minneapolis knows them.

The situation only seems worse with “The Yard” when we take into account the newest figures: private (i.e., Vikings-related and Sports Authority-related) uses of “The Yard” will take up about 60 days a year. Two whole months when the general public cannot access this park.

Thanks Connie. My objection isn’t so much that the park may be used for private parties on some days, although some reported numbers seem excessive, but how that use may limit or restrict the “design” of the space. I would think that we pose nearly intractable problems to our landscape architects when we insist that any design must be essentially temporary or mobile in nature; that we must be able to knock it down August through January or erect the corporate football/circus tents around or among any permanent amenities for those months. If two blocks of “big top” tents have to be erected every fall, what alternative do landscape architects have but to leave at least the vast interior of those two blocks as flat, open space. No trees, no plants, no structures, not even benches? And certainly very limited variations in topogaphy. And even if it’s a glorious sward of green, won’t it be trampled to mud every fall if even one weekend brings rain — or snow?

It seems to me that given the challenges of the space and conflicting uses, we may need a little more time to work out an innovative design than we are being told is possible. In other words, let’s not spend our whole budget on a rushed plan. If we have to put the two blocks in grass for now, perhaps we have no choice. Then design a better space to our own timetable and with more thoughtful input. That doesn’t mean the challenge will be met easily, but at least we won’t have the costs of starting over — or knocking down a pavilion and finding another location for a fountain and a sculpture — or ignoring past mistakes.