The Myth of Bassett’s Creek

I heard again recently the old complaint that north Minneapolis would be a different place if Bassett’s Creek had gotten the same treatment as Minnehaha Creek. Another story of neglect. Another myth.

You can find extensive information on the history of Bassett’s Creek online: a thorough account of the archeology of the area surrounding Bassett’s Creek near the Mississippi River by Scott Anfinson at From Site to Story — must reading for anyone who has even a passing interest in Mississippi River history; a more recent account of the region in a very good article by Meleah Maynard in City Pages in 2000; and, the creek’s greatest advocate, Dave Stack, provides info on the creek at the Friends of Bassett Creek , as well as updates on a Yahoo group site. Follow the links from the “Friends” site for more detailed information from the city and other sources.

What none of those provided to my satisfaction, however, was perspective on Bassett’s Creek itself after European settlement. A search of Minneapolis Tribune articles and Minneapolis City Council Proceedings, added to other sources, provides a clearer picture of the degree of degradation of Bassett’s Creek — mostly in the context of discussions of the city’s water supply. This was several years before the creation of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners in 1883 — a time when Minnehaha Creek was still two miles outside of Minneapolis city limits. The region around the mouth of Bassett’s Creek was an economic powerhouse and an environmental disaster at a very early date — a mix that has never worked well for park acquisition and development.

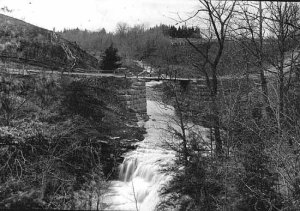

Idyllic Minnehaha Creek, still in rural surroundings around 1900, quite a different setting than Bassett’s Creek, which had already been partly covered over by then. (Minnesota Historical Society)

“A Lady Precipitated from Bassett’s Creek Bridge”

Anfinson provides many details of the industrial development of the area around the mouth of Bassett’s Creek from shortly after Joel Bean Bassett built his first farm at the junction of the river and the creek in 1852. By the time the Minneapolis Tribune came into existence in 1867, industry was already well established near the banks of the creek. A June 1867 article relates how the three-story North Star Shingle Mill had been erected earlier that year near the creek. The next March an article related the decision to build a new steam-powered linseed oil plant near the creek on Washington Avenue.

Even more informative is a June 27, 1868 story about an elderly woman who fell from a wagon off the First Street bridge over the creek. “A Lady Precipitated from Bassett’s Creek Bridge, a Distance of Thirty Feet,” was the actual headline. (I’m a little embarrassed that I laughed at the odd headline, which evoked an image of old ladies raining down on the city; sadly, her injuries were feared to be fatal.) But a bridge height of thirty feet? That’s no piddling creek — even if a headline writer may have exaggerated a bit. The article was written from the perspective that the bridge was worn out and dangerous and should have been replaced when the city council had considered the matter a year earlier.

By 1871 the Washington Avenue bridge over the creek had been replaced by the only large stone arch bridge in Minnesota, according to the Tribune. “It was built to last a century, and will stand that long unless torn away to give place to a superior structure,” a Minneapolis Tribune writer speculated on September 21, 1871, unable to foresee that the creek itself would disappear from the landscape in about two decades. The point of this citation is that the area was so developed that bridges over the creek were already being replaced, they were worn out, decaying, a dozen years before Minneapolis had a park board. But it gets worse.

“The mammoth sewer called Bassett’s Creek”

By 1876 Bassett’s Creek was a nuisance to many. In April, the City Council was petitioned to straighten Bassett’s Creek and sink it in a canal. The next month Mayor Ames wrote to the council urging the improvement of the city water works, which at that time took in city water from the Mississippi River below the mouth of Bassett’s Creek.

“The water supplied by the Water Works is unfit for domestic purposes. All the drains in the upper portion of the West Division of the city — and especially that mammoth sewer called Bassett’s Creek — empty into the river above the Water Works and the disease generating poison, somewhat diluted, is distributed to those of our citizens living along the water mains.”

— Mayor Albert Ames, in a letter dated May 24, 1876 cited in Proceedings of the City Council, March 21, 1877

City engineer Thomas Rosser used similar language later in 1876 referring to the “sewer known as Bassett’s Creek.” Professor S. F. Peckham, a chemistry professor hired to analyze city water samples, agreed in March 1877 that “Bassett’s Creek in its present condition is practically an open sewer.” The city council’s select committee on water supply went a step further, noting on March 17, 1877, that “local contamination [of the water supply] from city sewerage, especially from Bassett’s Creek, is such as to cause grave apprehensions of disease.”

In an editorial on October 18, 1882 the Minneapolis Tribune called the creek a “prolific source of filth and poison,” and surmised that “the suggestion that a solution of the difficulty might be found in turning the creek into a sewer, the outlet of which should be below the falls, is certainly worthy of consideration…the old bed of the stream could then be filled up.” About the same time the paper reported that developer Louis Menage proposed to straighten the creek across 20 acres of property he owned west of Washington Avenue so that he could build houses there.

By this time, of course, the prominent residents of the Bassett’s Creek area nearer the river had departed. Anfinson writes, “As the sawmills began to take over the nearby river front in the late 1860s, the noise and air pollution began to bother the homeowners south of Bassett’s Creek. Bassett moved to Nicollet Island in 1870.”

Bassett’s Creek was of no interest to anyone who wanted to create beautiful and healthful places of relaxation and revitalization by the time the park board was created in 1883. Even Horace Cleveland, one of the most effective proponents of preserving land for public use, and the most ardent supporter of securing the Mississippi River banks below St. Anthony Falls for a park before they could be spoiled by industry, saw little potential in Bassett’s Creek in the populated neighborhoods of north Minneapolis. In the important “suggestions” he made to the new park board in June, 1883, which created a blueprint for parks in Minneapolis that was followed for decades, Cleveland saw only possibilities to minimize the deleterious impact of a polluted Bassett’s Creek.

“The region traversed by Bassett’s creek is one which threatens danger to the health of the future city, and its proper treatment is a problem that demands early attention. No one has said anything to me in regard to it, and it was only as I have crossed it at one or two different points that I have had an opportunity to observe it. I venture to make only one suggestion in regard to it, which is that the risk of malaria from it will be greatly increased by the construction of causeways across it at the points where it is crossed by streets, as the valley between every two streets would thus be converted into a deep pit, impervious to the air, whereas if bridges are used, the winds would still have free passage up and down the valley.”

— Horace W. S. Cleveland, Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis, June 2, 1883

A year later, the Tribune noted in an article on a real estate boom in North Minneapolis that the “work of filling up Bassett’s Creek goes steadily on.”

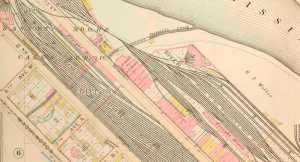

A straightened Bassett’s Creek as seen in 1892 plat map. Western Avenue, now Glenwood Avenue, crosses the center of the map, 6th Avenue North, Olson Memorial Highway, is at the top. (John R. Borchert Map Library.)

The creek has been straightened and buried under railroad yards in 1892 plat map. (John R. Borchert Map Library.)

Plans for straightening, channeling, or burying the creek continued. On December 30, 1888 the Tribune reported that a survey of Bassett’s Creek had been made by the city engineer from its mouth to the second crossing of Western Avenue (now Glenwood Avenue at about Dupont Avenue North). “It is proposed to straighten the creek and build a wall on each side seven feet high,” the paper reported

The result of those efforts is seen in these two segments of the 1892 Minneapolis plat map.

Park Planners Preferred Cheap, Pretty and Unused

As I’ve said and written on many occasions: the park board in Minneapolis — like park organizations nearly everywhere else — has always been opportunistic; it acquired land and developed parks and playgrounds when it could do so at little or no cost and when few people complained of economic injury due to parks. That’s why nearly all parks, in Minneapolis and elsewhere, are on land that had little or no economic worth or potential. In other words, parks are on land that was given away or could be purchased cheaply. It was land that had little value, because it had few other uses.

Theodore Wirth makes my point with his description in the park board’s 1906 annual report of land he recommended adding to Glenwood Park. He wanted to expand the park to include land that was “irresistably attractive with its wooded hills and dells and small woodland meadows of irregular outlines. For all other purposes this land is almost useless, for park purposes it is made to order.”

Park land had to be cheap; it also had to be scenic. Especially in the early days of park building. (In the 1900s, when creating playgrounds became an accepted role for park boards, more parkland was sought in developed areas.) That’s why the first national and state parks were established in the midst of breathtaking scenery like Yellowstone, Yosemite, Niagara Falls and Minnehaha Falls, instead of the cotton fields of Georgia or the corn fields of Illinois.

The rural setting of Minnehaha Creek, possibly at Penn Avenue, ca. 1890. (Minnesota Historical Society.)

The third thing to keep in mind about park acquisition a century and more ago was the laudable and visionary goal of preserving attractive features of the landscape. When there was still so much that was undeveloped to be preserved, park founders gave little thought to what needed to be reclaimed. By all three tests — cost, appeal and use — Minnehaha Creek topped Bassett’s Creek as worthy of park board attention. The land around Minnehaha was mostly donated and very charming. And it ended in a beautiful waterfall and a lovely secluded glen to the river, where a single mill had been abandoned years before. To suggest that the two creek valleys were treated differently for other reasons is a stretch.

Where Bassett’s Creek was cleaner and more attractive west of industrial north Minneapolis, it was protected, preserved and made part of the park system (when the land around it was donated to the park board or sold cheaply!) at Bryn Mawr, Glenwood (Wirth) Park and Bassett’s Creek Park. That a parkway was never built beside it is the topic for another post.

Would a clean, meandering Bassett’s Creek from Bryn Mawr through the post-industrial wasteland of near-near-north to the Mississippi be a wonderful amenity today? Would it enhance the appeal and value of more property in the core city? It would be amazing — and I applaud the efforts of people like Dave Stack to keep the issue alive. Reclaiming any of this buried creek will require many more years of extraordinary effort, creative thinking and gutsy investment. Perhaps it’s impossible. In any event, it’s likely to happen only after further investment and development along the Mississippi River itself — opportunists, remember — and the effort will not be advanced by uninformed claims of past neglect.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

[…] The Myth of Bassett’s Creek 2011 […]

I wonder if they chose not to save it because the flight. Since no one was their to advocate for a real clean up, and possibly because the area was very diverse, they chose to just cover it up instead of just deal with the mess they made and allowed to happen in the first place.

Thanks for your comment, Kristel. I wish people with your sensibilities and your organization’s mission had been around 150 years ago. We’ve now learned that remediation is much more expensive in time, money and health than protection and prevention. Fortunately our view of our relationship with the earth and its resources, and with each other, has improved since Bassett’s Creek was polluted, straightened, then buried. At that time, however, the primary diversity issue in North Minneapolis was whether someone had immigrated from New England or Northern Europe and which European languages they spoke in their homes and churches or synagogues. The demographics of the city have changed significantly since then, so diversity would have been understood differently then than now.

As for the “they” you refer to, I was writing of the actions taken specifically by the park board to preserve natural features of the landscape. I have not looked into what other components of city, county or state government or other organizations could or should have done to prevent or remediate damage to Bassett’s Creek.

David C. Smith

Wow David Smith – terrific research and a good forum on the subject of Bassett Creek. Hope you or someone equally motivated would do the same kind of research on Shingle Creek. I grew up 0n Webber Parkway across the street from Webber Park. Shingle Creek flowed through the park into a pond and then over a spillway at the far end. It continued in from of the old Library on its meandering way to the Mississippi. It was a great place t

then. In about 1960 all that was crudely changed and the creek was rerouted behind the park like a drainage ditch. Paradise lost!

Thanks for reading, Audie. You might be interested in reading the histories of Shingle Creek Park and Webber Park at minneapolisparks.org. Click on “Parks and Lakes” and go to either of those parks. On the park page click on the “History” tab. Those pages will provide more history of those properties as parks at least. I have not looked into the history of pre-park Shingle Creek as much as I have for Bassett’s Creek. That might be a good project one of these days.

I played at the creek in the mid-1950’s. At that time the area of the creek that is close to the parkway (north of the Chalet) had rocks that you could walk across. We would cross back and forth. My dad — who was born in 1906 — used to tell me that he and his buddies would walk or bike from 21st & Bryant to Bassett Creek north of the Chalet and swim in the area where the creek widens near the parkway and Golden Valley Road. Sweeney Lake also has a little falls (I don’t know if it’s natural) where it empties on the northeast end of the lake and winds around behind Courage Center, and I believe it must enter Bassett Creek back in that area.

Thanks for adding to our picture of the creek, Patty.

In the early 1960’s I grew up at 1717 York Ave N. Attended St. Margaret Mary. At the creek almost daily. I caught in the creek perch, bullheads, rock bass, small mouth bass, large mouth bass, crappies and sunnies. From the rocks north of the chalet to Sweeney Lake the creek was wonderful. Now??? Such a sin. Shame on you Minneapolis. Shame.

Thanks for your comment, Gary. Any suggestions for improvement?

OMG. Do you have a million dollars? Seriously, I am a lawyer not a hydrologist/environmental expert. I can give money. I can work. But you need experts to design a restoration of this asset. It is a muddy trench compared to what it was in the 60’s. The reality is we have polluted most of our lakes and streams. I think when it is gone, it is gone.

[…] Boom Island in what is now the Warehouse District. The creek got its name from Joel Bean Bassett, who built his first farm at the creek’s mouth in 1852. Within a generation of his arrival, mills and rail yards turned the creek into an […]

I lived at 1717 York Ave. N. in the 60’s. I fished the Bassett’s Creek every day I didn’t have sports after school. This area was by Wirth Park up to Sweeney Lake. I caught all species of fish. The water was clear and clean. There were waterfalls and rapids. I caught panfish, rock bass, largemouth and smallmouth bass, perch, bullheads.

After I graduated from college I discovered that the creek had been straightened and flattened. It was ruined. I would like to see photographs of it in those days if any is available.

Thanks for your comments, Gary. I don’t think I’ve ever seen pictures of that section of the creek in that era. Most of the images I’ve seen at the Park Board are from the 1930s when a WPA project focused on the creek downstream from Wirth Park. I’d be happy to post pictures of the creek if readers have any that are identifiable. By the way, some of the earliest pictures I’ve seen of what is now Wirth Park may soon be scanned and published, along with a few hundred more images, by Minnesota Digital Library. I’ll keep readers posted on the course of that potential project.

If memory serves this was before the golf course was established. The course ruined the creek. It was like being in Colorado. It was amazing. As a kid it never entered my mind to photograph it. Can you imagine catching rock bass, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, sunbird, crappies and perch in a pond at the head of a rapids that was maybe 300 years long? The rapids was full of large boulders that created smaller pools and falls. The timeframe was 1960 to 1967.

Your memory has betrayed you! The golf course at Wirth Park celebrates its centennial this year. The first nine holes opened in 1916 and another nine holes were added in 1919. But your memory may have a good excuse: the back nine holes of the course were extensively rearranged in 1968 and that might have caused some of the changes you noticed. I’m not a golfer, so I am not familiar with the layout of the course or the changes that were made at that time, but it seems a likely explanation. Any golfers want to weigh in on changes to the course at that time?

David –

Yes! You are correct. I remember now. The course was up near the chalet! We used the hills in winter for sledding! Well, I was 10 -15 years old then. Back then we saw no golfers near the creek, though. The course did not touch the creek except maybe near Glenwood Hills Hospital. But, yes, maybe on the south side. At some point the course overtook both banks, and the creek was never the same.

Do you remember the rapids as the creek approached the chalet? We should all gather and walk it. I would love to see photos!

Thank you for refreshing my 63 year old brain.

Thanks for the reminiscence, Gary. One of the reasons I started this site was to keep some memories alive. We have to remember before we can decide if we should preserve or improve. I would encourage anyone with pictures of the creek in the middle of the last century, wow that sounds like long ago, to contact me at my email, minneapolisparkhistory[at]q.com.

[…] blueprint for Minneapolis’s park system in 1883, made his first visit to Glenwood Spring near Bassett’s Creek in north Minneapolis in the spring of 1888. In a letter to the Minneapolis Tribune, published April […]

I’ve lived near bassett creek my whole life (25+yrs). when i was just a kid i used to play down by the creek with all the other neigborhood kids, back then the creek was alot cleener and nicer, it was an area where parents wouldnt have to worry about thier kids getting dirty or playing in a park or place occupied by drifting and the bleek dimness of sewage. now days, this is what it looks like and i would never allow or dream of my kids playing around or near such a prudent and neglected creek. Once in a while i still like to take a walk on the trails & parkways of theodore wirth and it looks nothing like it used to when i was a kid, the railroad bridges are deteriorating and the creek beneath is suffering from the dis-repair and the attempt to fix the bridge seems to be causing more damage than it seems, the creek flow has significantly slowed or has completely stopped all together near the area of these bridges im speaking of, the placement of irrigation tubes is completely wrong and too high for the water to flow through. I’m certain the creek will slowly return to its natural glory if this matter is resolved and the flow can continue down stream… i would like to establish and produce an effort to help this particular problem. anyone that has any details on who to contact or what process should be made to seek help and support for the issue. please let me know, i’d like to see the area that i have lived near my whole life flourish and retain its natural flow and beauty it once had. NB 2.26.13 (!NC)

Thanks for reading, Neil. I suggest you check out the links in the second paragraph of the post to find others who are trying to improve Bassett’s Creek. I wish you all well in that effort.

I also just discovered new comments by H. W. S. Cleveland on Bassett’s Creek environs that I will post soon.

(NOTE: I later wrote about those comments by Cleveland here.)

[…] The park board attempted to buy the east bank of the river gorge, downstream from the University, in the late 1880′s, as recommended by Cleveland, but the owners of the land challenged nearly all park board appraisals and the board abandoned the effort, at least for a time, leading to Cleveland’s complaint to Olmsted. He was referring at that time only to the splendid bluffs and unspoiled gorge ushering the wild river south below the falls. If Cleveland and the “best men” couldn’t “save” those picturesque, precipitous and largely unused bluffs, it should be no surprise that the park board had little interest in the river banks on the flat, unremarkable land above the falls, which was ideally suited for railroads and industry. (For a snapshot of the industrial west river bank, see an article on the area around the mouth of Bassett’s Creek.) […]

[…] Interesting thoughts from readers on city and park board treatment of Bassett’s Creek: […]