Archive for the ‘Dr. Martin Luther King Park’ Tag

100 Years Ago: Altered Electoral Map and Shorelines

What has changed in 100 years? A few times on this site, I have looked back 100 years at park history. I’ll expand my scope this year because of extraordinary political developments. Politics first, then parks.

The national electoral map flipped. The electoral map of the 1916 Presidential contest is astonishing. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, won a close re-election against Republican candidate Charles Hughes, a Supreme Court Justice. Compare red and blue states below to today. Nearly inverted. The Northeast, Upper Midwest and Far West — well, Oregon — voted alike. Republican. And lost.

The 1916 electoral map was nearly opposite of the 2016 electoral map in terms of party preference. Unlike 2016, President Wilson won both the popular vote and the electoral vote, but his electoral-vote margin was smaller than Donald Trump’s. If the total of votes cast in 1916, fewer than 19 million, seems impossibly low even for the population at that time, keep in mind that only men could vote. (Source: Wikipedia)

While Minnesota’s electoral votes were cast for the Republican — although Hughes received only 392 more votes than Wilson out of nearly 400,000 cast — Minneapolis elected Thomas Van Lear as its mayor, the only Socialist to hold that office in city history. One hundred years later, Minneapolis politics are again dominated by left-of-center politicians.

The population of Minneapolis in 1916 and 2016 was about the same: now a little over 400,000, then a little under. Minneapolis population peaked in mid-500,000s in mid-1950s and dropped into mid-300,000s in late 20th Century. One hundred years ago, however, Minneapolis suburbs were very sparsely populated.

The world 100 years ago was a violent and unstable place. World War I was in its bloody, muddy depths, although the U.S. had not yet entered the war, and Russia was on the verge of revolution. Now people are killed indiscriminately by trucks, guns, and bombs. People worldwide debated then how to address the excesses of capitalists, oligarchs and despots unencumbered by morality. We still do.

One notable change? Many Americans campaigned in 1916 to put women in voting booths, in 2016 to put a woman in the Oval Office.

Continuing Park Growth: North and South

How about progress in parks? The Minneapolis park board added significantly to its playground holdings in 1916 and 1917 as public demand for facilities and fields for active recreation increased. In North Minneapolis, Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park was expanded and land for Folwell Park was acquired. In South Minneapolis, Nicollet (Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.) Park and Chicago Avenue (Phelps) Park were purchased and land for Cedar Avenue Park was donated. In 1917, the first Longfellow Field was sold to Minneapolis Steel and steps were initiated to replace it at its present location.

One particular recreational activity was in park headlines in 1916 for the very first time. A nine-hole course was opened that year at Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park, the first public golf course in Minneapolis. Golf was free and greens weren’t green, they were made of sand. In less than ten years, the park board operated four 18-hole courses (Glenwood [Wirth], Columbia, Armour [Gross], and Meadowbrook) and was preparing to add a fifth at Lake Hiawatha.

The Grand Rounds were nearly completed conceptually, when first plans for St. Anthony Boulevard from Camden Bridge on the Mississippi River to the Ramsey County line on East Hennepin Avenue were presented in 1916. Park Superintendent Theodore Wirth also suggested that the banks of the Mississippi River above St. Anthony Falls might be made more attractive with shore parks and plantings, even if the railroads maintained ownership of the land. One hundred years later we’re still working on that, but have made some progress including the continuing purchase by the Park Board of riverfront lots as they have become available.These have been the only notable additions to park acreage in many years.

One important result of the increasing demand for playground space in Minneapolis one hundred years ago was the passage by the Minnesota legislature in 1917 of a bill that enabled the park board to increase property tax collections by 50%. In 2016, the Park Board and the City Council reached an important agreement on funding to maintain and improve neighborhood parks.

Altered Shorelines

In a city blessed with water and public waterfronts, however, some of the most significant issues facing the Minneapolis park board in 1917 involved shorelines — beyond beautifying polluted river banks.

The most contentious issue was an extension of Lake Calhoun, a South Bay, south on Xerxes Avenue to 43rd Street. Residents of southwest Minneapolis wanted that marshy area either filled or dredged — dry land or lake. There was no parkway at that time around the west and south shore of Lake Calhoun from Lake Street and Dean Parkway to William Berry Parkway. As a part of plans to construct a parkway along that shoreline, the park board in 1916 approved extending Lake Calhoun and putting a drive around a new South Bay as well.

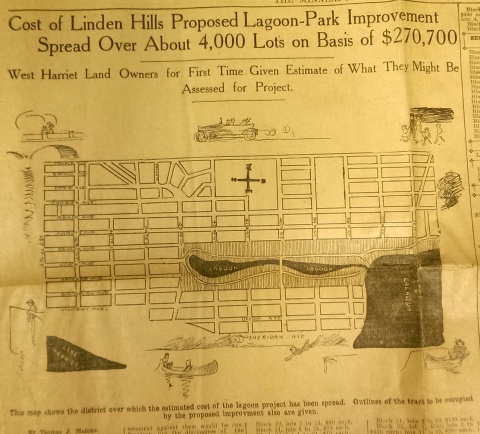

This drawing from a 1915 newspaper article shows the initial concept of a South Bay and outlines how it would be paid for. (Source: Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, June 20, 1915)

The challenge, of course was how to pay for it. The park board’s plan to assess property owners in the area for the expensive improvements was met with furiuos opposition and lawsuits. Many property owners thought that assessments they were already paying for acquisitions and improvements over the years at Lake Calhoun, Lake Harriet and William Berry Park were too heavy. The courts eventually decided in favor of the park board’s right to assess for those improvements, but by then estimated costs for the project had increased and become prohibitive and the South Bay scheme was abandoned.

Instead land for Linden Hills Park was acquired in 1919 and the surrounding wet land was drained into Lake Calhoun in the early 1920s. Dredged material from the lake was used to create a better-defined shoreline on the southwestern and northwestern shores of the lake in 1923 in preparation for the construction of the parkway.

Flowage Rights on the Mississippi River and a Canal to Brownie Lake

Minneapolis parks also lost land to water in 1916. The federal government claimed 27.6 acres of land in the Mississippi River gorge for flowage rights for the reservoir that would be created by a new dam to be built near Minnehaha Creek. Those acres, on the banks of the river and several islands in the river, would be submerged behind what became Lock and Dam No. 1 or the Ford Dam. In exchange for the land to be flooded, the park board did acquire some additional land on the bluffs overlooking the dam.

The other alteration in water courses was the dredging of a navigable channel between Cedar Lake and Brownie Lake, which completed the “linking of the lakes” that was begun with the connection of Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun in 1911. The land lost to the channel was negligible and probably balanced by a slight drop in water level in Brownie Lake. (A five-foot drop in Cedar Lake was caused by the opening of the Kenilworth Lagoon to Lake of the Isles in 1913.)

Another potential loss of water from Minneapolis parks may have occurred in 1917. William Washburn’s Fair Oaks estate at one time had a pond. I don’t know when that pond was filled. The estate became park board property upon the death of Mrs. Washburn in 1915. Perhaps in 1917 when the stables and greenhouses on the southwest corner of the property were demolished, the south end of the estate was graded and the pond was filled. Theodore Wirth’s suggestion for the park, presented in 1917, included an amphitheater in part of the park where the pond had once been.

The Dredge Report

The year 1917 marked the end of the most ambitious dredging project in Minneapolis parks — in fact the biggest single project ever undertaken by the park board until then, according to Theodore Wirth. The four-year project moved more than 2.5 million cubic yards of earth and reduced the lake from 300 shallow acres to 200 acres with a uniform depth of 15 feet.

That wasn’t the end of work at Lake Nokomis, however. The park surrounding the lake, especially the playing fields northwest of the lake couldn’t be graded for another five years, after the dredge fill had settled.

Dredging may again be an issue in 2017 if the Park Board succeeds in raising funds for a new park on the river in northeast Minneapolis. Dredges would carve a new island out of land where an old man-made island once existed next to the Plymouth Avenue Bridge. But that may be a long time off — and could go the way of South Bay.

Park Buzz

One other development in 1917 had more to do with standing water than was probably understood at the time. The Park Board joined with the Real Estate Board in a war on mosquitoes. However, after spending $100 on the project and realizing they would have to spend considerably more to achieve results, park commissioners terminated the project. It was not the first or last battle won by mosquitoes in Minneapolis.

As we look again at new calendars, it’s always worth taking a glance backward to see how we got here. For me, it is much easier to follow the course of events in Minneapolis park history than in American political history.

David C. Smith

Comments: I am not interested in comments of a partisan political nature here, so save those for your favorite political sites.

You Think a Dog Park Was Controversial?

After holding public hearings and receiving “various communications objecting to it,” on April 20, 1960, the Minneapolis park board rescinded an agreement with Minneapolis Civil Defense to build a “demonstration atomic bomb fallout protective shelter” in Nicollet Park. The board granted permission to build the demonstration fallout shelter at The Parade instead. Was it ever built? I don’t know.

This 1960 instructional booklet included plans for a fallout shelter, presumably similar to the one Minneapolis Civil Defense wanted to build at The Parade. This image is from authentichistory.com. The booklet is also available for sale on e-Bay at the time of this posting–if you’re still worried, or think it would do any good.

In 1968 Nicollet Park was renamed Dr. Martin Luther King Park. The park was the focus of bitter debate over the past year. The issue was whether converting a small portion of the park into an off-leash dog park would desecrate the memory of Dr. King. The dog park was not built.

During the 1960 meeting at which the board approved the fallout shelter, it also granted permission to the Twin City Walk for Peace Committee to hold an open air meeting at The Parade at the conclusion of a “peace walk.”

As a point of reference, Stanley Kubrick’s classic film of the atomic-bomb age, Dr. Strangelove, was released in 1964.

David C. Smith

Dr. Martin Luther King Park: The Naming of a Park

The Minneapolis neighborhoods near Dr. Martin Luther King Park have become embroiled in an argument over the name of the park and whether that name confers special meaning on park land. At issue is whether designating a portion of the park as a dog park, where dogs could be off leash, would desecrate the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Here are the facts as recorded from the Proceedings of the Board of Park Commissioners, January 1st to December 31st For Year 1968:

April 17: Under the heading “Petitions and Communications.” Minneapolis NAACP requests Nicollet Field be renamed “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Park.” The board referred the request to the Planning Committee.

June 19: Also under “Petitions and Communications.” The Southside Activities Council expresses unanimous support for renaming Nicollet Field, “Martin Luther King. Jr. Memorial Park.”

October 9: After amending the park board’s Policy Statement to permit parks to be named after “persons of other than local significance” when “appropriate and desirable,” the board voted to change the name of Nicollet Field to “Dr. Martin Luther King Park.”

There is no explanation for the inconsistency of the use of Dr., Jr. or Memorial in the various proposals and the final resolution. But there has been no consistency in the use of Dr. or Jr. in general usage then or now.

I was curious about the origin of the park board’s Policy Statement on the naming of parks. I did find an entry in the Proceedings for May 2, 1934 that I believe established the board’s policy.

A bit of background: The park board had nearly completed the construction of a park across the street from the new post office downtown in 1934. It was a park the park board did not want to build, but was convinced to build by the City Council. The U.S. Postal Service wanted a new post office in Minneapolis, but was reluctant to build one without a proper approach or environment. The USPS wanted a park. The City Council finally persuaded the park board to go along. The park board did so reluctantly, especially given the colossal failure of The Gateway park only a couple blocks west.

So the park board had a new park, with a grand new statue — the Pioneers Statue, which was moved for a second time last summer to B. F. Nelson Park. All the park needed was a name. Everyone had suggestions, but three names seemed to generate the most interest.

Lafayette Park. May 20, 1934 would be the centennial of Lafayette’s death and some thought the park should be named for him and dedicated on that date.

Roald Amundsen Park. This was the choice of the Norwegian community. Amundsen, a Norwegian explorer, was the first to reach the South Pole in 1912 and had died in 1928 while on a rescue mission in the Arctic.

General Pulaski Park. The Polish community proposed naming the park for Kazimierz Pulaski the Polish soldier of the Revolutionary War who was credited with creating the first American cavalry unit. An effort to rename Bottineau Field for Pulaski had failed the year before.

Perhaps not wishing to offend any nationality, the Special Committee on Nomenclature offered a new policy for the park board on May 2, 1934. The statement noted that the City Council and the Board of Education had chosen to name streets and schools to perpetuate the names of Presidents, explorers of local and international fame, and artists, writers and scientists of world-wide importance, “all of which your committee believes to be commendable.”

“However, some official body should lay particular emphasis on perpetuating legendary and place names of local significance and the names of those of our own citizens who from time to time have played important parts in the molding of our city — its physical structure, its artistic and spiritual background.

“Our parks are admirably suited for such a purpose, and such a purpose most admirably furthers the work of this Board in instilling in the minds of the youth who frequent our parks the ideals of useful citizenship…Here is something intimate — some one of us has achieved honor — our fathers knew him — we know his descendants. We too might achieve such honor by leading exemplary and highly useful lives.”

So, the committee recommended that “your honorable Board restrict the names to those commemorating men and women of local civic achievement and historical importance and legendary and place names of local significance…”

The statement was adopted and apparently still in place in 1968. At the meeting after the policy was adopted (May 16, 1934), the same committee recommended the name “Pioneers Square” for the new park that until then had been referred to simply as “Post Office Square” or the more Orwellian “Block 20.”

It was this policy that the park board had to amend in October 1968 to be able to rename Nicollet Park, Dr. Martin Luther King Park.

By the way, Nicollet Park was not named directly for the French cartographer Joseph Nicollet. It was named for the avenue named for him, which formed the park’s western border.

David C. Smith

Comments (10)

Comments (10)