Minneapolis Elections: All the Results

I was recently asked about a website that provided complete election results for Minneapolis city offices from City Council to Park Board, Library board and more. I first mentioned it in a post in 2011 and it’s bigger and better than ever.

It’s Minnesota Election Trends Project, which was created by Neal Baxter in 2004. For political geeks and policy wonks, it’s priceless. You can find not only fascinating anecdotes about city elections but a list of every elected official and the results of every city referendum since “Mni” and “polis” were mashed together. The site has also expanded to cover elections in more municipalities in the state.

The site might be a good place to start if you’re curious about past park commissioners and their roles in the issues addressed in my last post. What did they stand for? What motivated them? The site will have all the names to get you started. If you find something interesting, send it to me as a comment here.

Even if you aren’t interested in historical research but have already finished the NYT crossword and don’t have the stomach for more doomscrolling, take a look.

David Carpentier Smith

The Minneapolis Park Board Has Never Been and Shouldn’t Be the Deed Police

Horrors! The Minneapolis Park Board bought 49 acres of land near Lake Hiawatha and Minnehaha Parkway for $1. How dare they? They should have known the donor, er… seller, was a real estate developer who inserted racial covenants on the deeds to the surrounding property that prohibited ownership or occupancy by non-whites. Let’s cancel that sale from 100 years ago!

I recently wrote a letter to the editor of the Minnesota StarTribune, published November 29, in which I praised the Mapping Prejudice Project which identifies racial covenants in property deeds. The project has examined property deeds in Hennepin County to identify those that contain racial covenants inserted between 1910 and 1955. The covenants prohibited ownership or even residence by Black people on those properties. The project identified more than 8,000 racial covenants in Minneapolis deeds and three times that many in suburban Hennepin County.

Writing racial covenants in deeds was a deplorable practice, especially by the developers and realtors who created those covenants, and deserves to be exposed. They should be called out and held to account. If their heirs or successors have an explanation, let’s hear it. I urged caution, however, in what we attribute to those covenants.

I am writing today to explain in greater length than an editorial page in a newspaper permits why I objected to some claims in the StarTribune column and in the sources cited in that piece.

I took issue with a column “The link between racial covenants and the development of Minneapolis parks” in the November 16 paper that argued “agreements between land developers and the Minneapolis Park Board created a network of exclusive whites-only neighborhoods with ample public land.” I saw no evidence in the column that supported the claim that the park board agreed with anyone to create such neighborhoods. I don’t believe there is any evidence, at least I haven’t seen any. The acceptance of free or cheap land for parks proves nothing.

The claim in the StarTribune column was based in part on a deceptive graphic presentation on the Mapping Prejudice website entitled “Greenspace, White Space: Real estate, racial segregation, and the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.” Much of the same material is presented in articles at Landscape and Urban Planning and Annals of the American Association of Geographers.

In those pieces the authors justly castigate realtors and developers, particularly Edmund Walton and Samuel Thorpe, for promoting whites-only enclaves. Walton and the company he created, led by Henry Scott after Walton’s death in 1919, was responsible for racial covenants primarily in developments near Cedar Lake and in the Longfellow neighborhood near West River Parkway. Thorpe promoted racial exclusivity in his projects across southern Minneapolis, especially in Shenandoah Terrace just north of Minnehaha Creek between Chicago Avenue and 12th Avenue South, and even more prominently in Edina, most notably in the Country Club neighborhood.

As I pointed out in my letter to the StarTribune, however, “Throughout the period when racial covenants were used by some developers and realtors, the park board was acquiring land for parks wherever it could as cheaply as possible — as it always had done.”

The Context

From the creation of the park board in 1883, park commissioners tried to preserve open spaces and features of the landscape that were then considered especially attractive and worthy of preservation. They were also trying to locate parks in every neighborhood in the city, another laudable goal. Should they have ignored neighborhoods with some houses built or sold by racists? What would the city look like now if the park board had exercised such discrimination then?

Free or nearly free parkland helped make Minneapolis the city it is today, with ample open space for anyone who chooses to live here. Much of Minneapolis’s waterfront — creeks, lakes, and river — for instance, was donated or bought very cheaply for parks. The same is true for parts of the celebrated Grand Rounds, the parkways for pedestrians, bicycles, and cars that nearly encircle the city. No doubt some donors hoped the creation of parks would make their other land in the vicinity more valuable. But whether it did or not was beyond the park board’s mission. The park board was created to provide parks throughout the city, not police real estate transactions. The demand for parks was great, the supply of money to buy them wasn’t.

Park proponents at the time certainly argued that the creation of parks would increase the value of surrounding land, which would in time pay for the acquisition through higher property tax receipts. It was no secret that people would want to live near a park and would pay more to do so. Nothing nefarious about it. Supply and demand. Better views, it has been said, are one of the only things that money can buy. And land speculation in Minneapolis was rampant in the 19th and early 20th Century — with or without parks.

It was widely understood when the park board was created that the acquisition in the 1850s of the country’s most famous urban park, Central Park in New York, had increased surrounding property values so much that property tax revenue did pay for the park. The challenge for a younger city like Minneapolis was to acquire land for parks before it got too expensive, but also to provide parks near where people lived. Naturally, that meant acquiring land near more crowded neighborhoods first, which the park board did in the twenty-seven years before the first deed with a racial covenant. And they did so for the most part, Logan Park was an exception, without taking people’s homes.

Did some speculators or investors make money from giving land to the park board? Without a doubt — likely including some park commissioners, some of whom were in the real estate business. But did we all get a more livable city in return? I think we did. Should we care if someone made a few bucks by giving most of Lake Harriet, the Mississippi River banks, Minnehaha Creek, or many other acres of land to the people of Minneapolis, to us? More than 100 years later, we collectively still own that land and we get to argue over how to use it even as the city has become dramatically more diverse over the last century.

Admirable Objective

The exposure of racial covenants (some covenants in the 1910s also banned sale to Jews) takes on added importance today as some people insist on white-washing American history, refusing to acknowledge anything that is less than admirable in our nation’s past.

That effort is sad especially because what is most laudable in our history are efforts to overcome the errors, to correct the mistakes, to right the wrongs of those who came before us while maintaining the best of what they imagined.

The continuing struggle to expand their vision and ensure rights for all people, to bring “all are created equal” into the present day where it applies to every man, woman and child regardless of differences is what we should be most proud of. How can we be proud of that fight and the progress we have made if we can’t admit why the battles had to be fought. And still need fighting.

I appreciate that the intentions of the authors of pieces with which I disagree in part likely have the objective of getting us to match our actions with our lofty words. But the demand to acknowledge history, even its shameful moments, requires us to assess with clear eyes and some depth of understanding, context, and nuance the events of the past. I believe claims such as those made in the StarTribune, as well as some on Mapping Prejudice’s own website, fail that test.

A Fuller Picture

Mapping Prejudice identified more than 8,000 deeds in Minneapolis that contained racial covenants. What the project doesn’t tell us is what percentage of deeds that represents. A square mile in the most “gridlike” residential neighborhoods in north and south Minneapolis hold over 3,000 parcels of land. (That’s 8 blocks north-south by 16 blocks east-west, assuming 24-30 lots per block.) Minneapolis’s total land area is about 54 square miles. I won’t attempt to guess how much of that land is categorized as residential for the purposes of the mapping endeavor.

Complicating the calculations is that, to my eye (I haven’t counted), in the map that Mapping Prejudice has published it appears that perhaps nearly half of the covenanted deeds within Minneapolis city limits are located south of 54th Street on the southern border of the city. That’s an issue because the section of Minneapolis from 54th Street to 62nd Street (roughly the Crosstown Highway) was annexed from Richfield in 1927. A random sampling of the properties that had racial covenants in those areas suggest that many of them predated the annexation, which hardly implicates the Minneapolis Park Board in colluding to favor whites-only neighborhoods. Perhaps Mapping Prejudice has a breakdown of those numbers; it would be useful. If my observations are accurate, that would reduce the share of covenanted deeds in the rest of the city, perhaps considerably.

While even one racial covenant is deplorable, their frequency may be useful in understanding the scope of the problem, particularly when indicting decades of park planning and acquisition as racist or claiming problems are or were systemic or structural. The question “How common?” matters because it gets to the issue of whether people cherry-pick data to buttress an argument. Is confirmation bias at work? Are researchers looking only for data or anecdotes that confirm their biases and ignoring what doesn’t?

These are my biases: I admire the efforts and foresight of park proponents over a century-and-a-half who helped to create a park system that makes life better in this city; I believe their overall contributions to our lives are praiseworthy; I don’t believe all of them were greedy profiteers; I believe they could have done some things better. I try not to let those biases interfere with my writing about parks, but they may creep in.

The StarTribune column and Mapping Prejudice site claim that “three-fourths” of the parks created between 1910 and 1955, were in neighborhoods with racial covenants. The parameter they establish is a park within a half mile of a property with a racial covenant in the deed is in what they call a racial-covenant neighborhood. A racial covenant anywhere within a square mile around a park, therefore, would doom that park to the scorned heap of parks allegedly created to entrench white supremacy — or provide green space exclusively for white people.

By that measure, one per square mile, just 54 racial covenants could be enough to condemn every park in Minneapolis. What lends a bit of irony to the “half mile” measure is that the park boards of that time were trying to meet a goal of having a neighborhood park within a half mile of every residence in the city because a half mile was judged about the farthest a mother could walk with two young children to play in a park. (Yes, it was a different time.) There was no effort to determine if that hypothetical mother of two was worthy of having a park to walk to.

In the two journal articles I cited, the authors use a different measure of racially restricted neighborhoods. Those studies define a “racial covenant neighborhood” as one in which one property within roughly a city block (0.1 mi.) has a racial covenant in a deed. If one racist nut lived near a park and put a covenant in their deed does that mean the park board entered into “agreements” to create green space for exclusively white neighborhoods? And that park would get lumped together with any other park with a racist nut within a stone’s throw of it (if it were Shohei Ohtani making the throw).

To adjust for the narrower definition of a racial covenant neighborhood in the journal articles, the authors opt for a different claim: not that three-fourths of new parks were in such a neighborhood, but three-fourths of new park acreage was in a “racial covenant neighborhood.” A big difference, but equally misleading.

The journal article cited in the StarTribune column claims that park acreage acquired within city limits in the racial covenant years was 1,163 acres of which 846 were in a “racial covenant neighborhood.” Those numbers overstate the impact of large acquisitions like 234 acres at Lake Hiawatha, which was abutted at the time of acquisition on the southeast corner by a Thorpe Realty development that included racial covenants.

Samuel Thorpe’s company began development of that property after the park board had already spent considerable effort defining the shores of nearby Lake Nokomis. The park board had dredged the lake to make it deeper and to fill the lowland around the lake to make it usable as recreation space. (MaryLynn Pulscher’s description is “land dry enough to drive on and water deep enough to sail on.”) The park board waited years for that muck to dry and settle before creating playing fields, a beach and parkway west of the lake. That’s when Thorpe sold the park board 49 acres of land to the east along Minnehaha Creek for a buck.

The change in measurement from the number of parks to park acreage maintains the appearance of racist acquisition even as the definition of a racial covenant neighborhood is narrowed to a less ludicrous distance than half a mile. Because by the measure of a covenant within a city block of a park, the park board created many more parks in those 45 years in neighborhoods that were not racially restricted than those that were. So we get park acreage as a measure instead, which looks worse — but on closer examination doesn’t hold up either.

To understand the distortion of the acreage measurement, compare Lake Hiawatha’s 234 acres, for instance, with Sumner Park, a 4.5-acre park in north Minneapolis that was acquired in 1915 at the request of Associated Jewish Charities. Sumner was not in a racial covenant neighborhood. It would take more than 50 Sumners to balance one Lake Hiawatha by the acreage measure cited. And the park board couldn’t have created fifty Sumner Parks without knocking down considerable existing housing around the city, which it didn’t have to do at Lake Hiawatha.

The Lake Hiawatha land was acquired in 1922 for the specific purpose of creating a golf course in south Minneapolis. It was one of the only undeveloped sites in the southern half of the city that was big enough for a golf course, and as a wetland it wasn’t good for much else in the eyes of urban residents 100 years ago, and therefore more affordable. (For more on the acquisition of Minnehaha Creek see Accept When Offered: A Brief History of Minnehaha Parkway.) North Minneapolis already had two popular golf courses, Wirth and Columbia, and Gross and Meadowbrook would be added before the course at Hiawatha was completed nine years later, so the park board was eager to extend what many residents considered a benefit to the southern half of the city.

Different land-use choices might be made today than in the 1920s, but to attribute racist motives to creating that park and lake is a stretch. Ironically, for those of the racist-park-board ideology, that golf course became a favorite of Black golfers in the city. And the land is currently being considered for a major overhaul to meet contemporary demands — which of course wouldn’t be possible if the land weren’t already owned by us.

It’s also worth noting that in the 1920s the park board also acquired all of Minnehaha Creek west of Lake Harriet to ensure the people of Minneapolis, us again, owned the entire creek bed from Edina to the Mississippi River. That acquisition of nearly 1.5 miles of creek was tainted too by the racial-covenant measure, primarily by 16 lots south of the creek in the 5200 block between Morgan and Logan Avenues. The covenants were in deeds granted by Thomas J. Magee who apparently subdivided that block in the late 1920s. That cluster and one lot across the creek contain the only creek-adjacent lots with racial covenants for the approximately three miles of creek from Edina to Portland Avenue.

Another case is St. Anthony Parkway from the Mississippi River to the eastern border of Minneapolis, including Deming Heights. That parkway’s 103 acres are tainted by a couple dozen lots with racial covenants on its far eastern end three miles of parkway from the river. Those covenants did not exist when the parkway was created and the park board never exercised any control over those lots. Nor should it have, in my view.

More acreage. Shingle Creek Parkway and Creekview Park, nearly sixty acres in north Minneapolis with covenanted property (developed by Girard Investment Company) only on its southern end near Webber Park. The park board reluctantly acquired the land in 1948 during the post-war housing boom only at the insistence of the City of Minneapolis. The city wanted the park board to acquire Shingle Creek and lower the bed of the creek to help drain the surrounding wet neighborhood so more housing could be built there as the city was bursting its seams. Very few new lots developed on either side of the creek carried racial covenants.

There were, however, racial covenants on deeds on the east side of nearby Bohannon Park which was deeded to the park board in 1935 by the city after it closed the workhouse on that site. A free park. Again, no signs of collaboration with racist developers to create whites-only neighborhoods, just another inexpensive neighborhood park for the majority of families whose property deeds did not contain racial covenants.

There were many more reasons for the park board to acquire park land than creating white enclaves. As the city’s population soared past 500,000 in the 1940s and housing was being built out to the city limits, the park board found a new method of acquiring land for parks: scouring the State of Minnesota’s list of land forfeited by delinquent taxpayers. Keep in mind that this followed nearly two decades of painful depression and then World War II. Nearly free land from the state list helped acquire all or portions of Bossen, Perkins Hill, Northeast, McRae, Hi-View and Peavey Parks. Both Bossen’s forty acres and McRae’s eight were supposedly tainted by racial covenants in the neighborhood.

The land between Bossen and Lake Nokomis to the northwest has one of the greatest concentrations of racial covenants in the city and once again some of those covenants predate the annexation of that land by Minneapolis. (A sampling of those properties finds four “grantors” names repeated many times: George and Sophia Pahl, Fred and Mabel Genevieve Cummings, Martin and Annie Nelson, and Arne G. and Sigrid Bogen. The A.G. Bogen Company also developed much of the land east of Pearl Park and Diamond Lake and recorded nearly 300 lots with racial covenants there.) On the other side of Bossen Field from those developments, however, the land north and east of the park all the way to Minnehaha Park is largely free of racial covenants; there are 24 parcels with racial covenants in 1.3 square miles. Most of them written by two couples, the Addys (7) and the Bogens (9).

As for McRae Park, reportedly a garbage site when acquired, whether it was imagined as green space for white people or not, it became a vital amenity serving Black neighbors too, as is evident from photos I posted several years ago here. (Be sure to read the comments, too.)

Schools and Playgrounds

Another way to reduce the cost of parks and maximize their usage, long championed by some park commissioners, was working with the school board to develop a park and school together. That was done in former Richfield locations at Armatage and Kenny in the late 1940s and early 1950s where many nearby lots had racial covenants, an undetermined portion of them also dating prior to becoming part of Minneapolis. The park board and school board also collaborated at Keewaydin and Hiawatha schools, and at Holmes Park and Cleveland Park to create playgrounds for schools, none of which were in racial covenant neighborhoods.

Another joint school/park project was at Waite Park in the northeast corner of the city. A housing development by Dickenson and Gillespie, Inc. north and east of the school and park attached racial covenants to deeds in 1947, a few months after the park and school boards acquired land. (The same outfit sold properties with racial covenants along Lake Nokomis Parkway west of the lake.) South and west of Waite Park there is not another property in all northeast Minneapolis, more than six square miles, with a racial covenant according to the Mapping Prejudice map. Should the park board not have collaborated with the school board to develop the Waite Park property, partly as a school playground, because of the covenants put on adjacent property?

In none of those locations, however, except perhaps Kenny Park, did the parcels with racial covenants outnumber those without racial covenants. Did the owners of those parcels not deserve schools or playgrounds because some other lots carried racial covenants? Should the park board have been deed police before or after it acquired land?

There is also the question of individual knowledge or acceptance of those perfidious covenants. I learned from a friend whose father died recently that when he went to sell the old family home he discovered that the deed included a racial covenant. He was appalled and quickly had that covenant removed from the deed. Little did he know or imagine that he grew up in a home that by itself could have damned the entire neighborhood as a “racial covenant neighborhood” according to some measures.

Was his father a racist? He didn’t think so. Were his neighbors? Who knows? Racists live among us. People who can’t accept differences live among us. People who want to paint everyone with broad brush strokes live among us too — as some are wont to do with park commissioners of a century ago.

Were some of those park commissioners racist? I would expect that some were. The challenge is to identify them. It’s easy to claim “institutional” racism because it absolves everyone, both accuser and accused. If injustices are “institutional” both everyone and no one is guilty, depending on the whims of the accusers and accused. It makes for lazy history.

In addition to accepting free or nearly free land for parks that are part of the alleged green space for whites only, the park board also accepted free or mostly free land during those years for Dorilus Morrison Park (the site of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts), Clinton Field, Stewart Park, Cedar Avenue Field, and Currie Park.

Disproportionate Claims

One entry on the Mapping Prejudice site claims: “Park acquisitions during this era were disproportionately in south Minneapolis, particularly along Minnehaha Creek, in the Nokomis neighborhood, and in the neighborhoods along the west bank of the Mississippi, parts of the city most densely blanketed with covenants.”

That is simply not true. Disproportionately? Compared to what? Minnehaha Creek I’ve already mentioned. In the area along the west bank of the Mississippi (the west riverbanks were acquired in 1902 after decades of trying) where Edmund Walton’s Seven Oaks Company inserted racial covenants in some the city’s highest concentrations, the park board made only three acquisitions in the 45 years that racial covenants existed: Brackett Park, Longfellow Park, and Seven Oaks Oval.

Seven Oaks Oval, which the developer gave to the park board, is a sink hole of two acres that has never been developed and probably didn’t attract many buyers to the neighborhood. It is shown as platted as a park in a 1903 map, long before racial covenants. As I have noted elsewhere, the park board has probably spent less money on Seven Oaks than any other park in the city.

Longfellow Park was a replacement for a park that was sold to the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company in 1917 during World War I (read more here) as the neighborhood became more industrial and after the school board had closed the adjacent Longfellow School. The new site was as close as the park board could come to replacing the surrendered land near East 28th Street and Minnehaha Avenue. It was on two undeveloped blocks that contained no houses in a thinly settled section of the city. The park board considered adding a third block, but because three houses had already been built on that block it’s assessed valuation was too high for the park board’s budget.

Brackett Field was in a section of the city that had some covenanted lots (a minority of property in the neighborhood, however) deeded mostly by Mary Greer east of the park and the Seven Oaks Company south and west of the park. A few lots with covenants were sold before the park was acquired but most were sold after park acquisition.

The park board acquired land on the margins of the city precisely because that’s where the city was growing and those sections did not have playgrounds yet. Minneapolis was overflowing and neighborhoods were expanding onto the last unbuilt land. The population of Minneapolis grew from 301,408 in 1910 to 521,718 in 1950. By contrast, the most populous suburb in 1950 was St. Louis Park at 22,644, triple what it was only a decade earlier. Minneapolis’s Black population increased from 2,592 in 1910 to 6,807 in 1950, or from 0.9% to 1.3% of the total population. (In 2020, 18.9% of Minneapolis’s population was Black.)

Not Much Happened for Nearly Two Decades

I noted earlier that the park board acquired some tax-forfeited land in the 1940s following the Great Depression and World War II. When considering the relationship of parks and racial covenants it’s worth noting that from the beginning of the Depression in 1929 until well after the war in the Pacific finally ended, the park board acquired very little land and didn’t pay for most of it. From 1930 until 1947, the park board added only six parks: Hiawatha School Playground was acquired from the school board; Bohannon Park was turned over by the city; the swamp of Todd Park was donated by the developer; Northeast Park was acquired largely through tax forfeiture; and Currie Park was purchased mostly with a cash donation for that purpose. The only acquisition the park board paid for was part of Bassett’s Creek Park, and that purchase in 1934 was to take advantage of a donation of thirteen acres of Bassett’s Creek a few years earlier by Arthur Fruen, a former park commissioner, adjacent to the mill he owned. The acquisition connected Bryn Mawr Meadows Park to Theodore Wirth Park (still named Glenwood Park then) along Bassett’s Creek and gave the park board ownership of all of that creek within city limits that’s above ground. {Read more about Bassett’s Creek here.)

By the “racial covenant neighborhood” measurement, two lots with racial covenants in their deeds a block west of Bassett’s Creek Park in the Bryn Mawr neighborhood, executed three and four years after the park was acquired in 1934, condemned all 60 acres of that park to the list of parks allegedly created for exclusively white neighborhoods.

The “racial covenant neighborhood” status of Bryn Mawr Meadows, which was acquired in 1910 isn’t quite clear as the western tip of that fifty-acre park is about 500 feet, just under a tenth of a mile, from the eastern tip of one lot in a development of about 60 lots west of Penn Avenue that Frank M. Groves and Hazel O. Groves attached racial covenants to 28 years later — not really a good example of the park board creating green space for a white enclave but perhaps classified as such for arguments sake.

Park acquisition isn’t the only thing that ground to a halt through part of the 1930s and 1940s. Especially during the war, there was almost no new residential construction. Both labor and materials for building were scarce. The result was a pent-up demand after the war for houses, schools and parks which led in part to the park and school collaborations in the late 1940s in the far south and north of the city.

Further complicating analysis of park acquisition during the time of racial covenants was a state law called the Elwell Law which permitted the park board to assess neighborhood property for the cost of acquiring and developing parks, if the neighborhood agreed to those assessments.

At the time it was viewed as a way to put decision-making in the hands of the people. In retrospect, however, it became evident that this method of park acquisition favored newer neighborhoods, wealthier neighborhoods, and neighborhoods with more single-family homes where people could afford assessments or where a park would increase the value of their property. Landlords of multi-unit buildings were not so keen to have a park developed nearby and have their costs increased.

Racial covenants on deeds did not always predict homeowners’ willingness to be assessed for parks, however. An example is the neighborhood around Kenny Park, part of the land annexed from Richfield, where many deeds contained racial covenants. That neighborhood declined to be assessed for a park in 1932, which delayed land acquisition as a joint project with the school board until 1948 and delayed any improvements until 1953.

From that perspective it doesn’t look like the park board provided an “exclusive whites-only neighborhoods with ample public land.” The people who bought property with racial covenants in the late 1920s had to wait more than two decades to get the parks the park board allegedly agreed to provide for their segregated neighborhood.

The park board formally ended the use of the Elwell Law in 1968, recognizing that acquiring park land should be a citywide responsibility, not dependent on a neighborhood’s willingness or ability to pay.

I have presented some examples of park acquisition issues that aren’t as simple as “racist or not” and don’t fit the narrative some researchers have created from Mapping Prejudice data. Those narratives contain little if any evidence to support claims that the park board participated actively or even passively in creating “whites-only” neighborhoods or favoring them with parks. There is neither correlation nor causation to support claims of collusion. I find it impossible to discern a racist pattern in park board acquisitions during the racial covenant years.

It is also quite clear that racist behaviors limited where Black people could live during those years. “Stories” on the Mapping Prejudice website provides some examples, and I have read others, of individuals encountering viciously discriminatory behavior in neighborhoods across the city with or without racial covenants. (See especially Eric Roper’s “Ghost of a Chance” podcast.) Even Bob Williams, the first Black player for the Minneapolis Lakers in 1955 encountered hostility when he bought a house on Clinton Avenue in South Minneapolis, although initial reactions cooled when neighbors learned from the cover story in the Picture magazine of Minneapolis Sunday Tribune that he was an NBA player.)

People should be held to account for racist and bigoted behavior, for a failure to treat people fairly and respectfully as individuals. That goal is not achieved by making unsupported generalized claims that merely suppose people’s motivations — past, present, or future — or convict them of the crimes of others.

I have had the good fortune to have lived and traveled extensively in other countries and I often encountered people who had firm opinions of the United States and Americans. I know if I were abroad now, I would face questions about present US government policies on several fronts. I would protest that I disagree strenuously with many current policies and I would be met at times with a shrug, “Well, it’s your country.” That’s a broad brush I would not want to be painted with. Would those who stretch the data from a worthwhile project like Mapping Prejudice to the breaking point judge me guilty anyway?

David Carpentier Smith

Riverside Park Staircase

I received a question from Elliot about Riverside Park that I can’t answer. Maybe you can.

“There are two limestone structures to the left and right of the main staircase at Riverside Park. They’re pretty overgrown. They look staircase-like, but I wonder if they were cascades for water to go down? I looked but couldn’t find any old pictures. Do you know about these?”

Any thoughts?

Riverside Park was one of four neighborhood parks designated by the first Board of Park Commissioners when the Board was created by the Minnesota Legislature in 1883. They designated a new neighbornood park in each quadrant of the city. The others were Central (Loring) Park, Logan Park and Farview Park. In addition to the neighborhood parks, the board planned to acquire connecting parkways–thanks to H.W.S. Cleveland’s plans–as well as land around one of the distant lakes to the southwest. Before it was officially named, the Park Board refered to it as Sixth Ward Park.

The neighborhood near Riverside Park was the only one that already had a park at that time although it served mostly as a pasture. Murphy Square, which had been donated to the city as a park nearly 30 years earlier, stood only a half-mile to the west of Riverside Park.

You can read a brief history of Riverside Park at the Park Board’s website. Click on the “History” tab.

David Carpentier Smith

See You at the Superintendent’s House

A last-minute notice: Stop by the Superintendent’s House, often called the Wirth House, in Lyndale Farmstead Park today, May 17, and say hello. Park Superintendent Al Bangoura has once again opened the historic house where he lives (he pays rent!) to the public as a part of the Doors Open weekend. The historic home was built by the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners as a home and office for Superintendent Theodore Wirth in 1910.

I’ll be there along with Al and others who are knowledgeable about the house history, including some former residents. We’ll be there today only — no Sunday opening this year — from 10 am to 5 pm.

If you still don’t have your copy of City of Parks, or you need one for a gift, you can buy one there and I’ll sign it for you. All proceeds to the park board.

David Carpentier Smith

Forfeited Land, Creative Additions

I recently received a note from Etch Andrajack about his fond memories of growing up near Hi-View Park in Northeast Minneapolis and what an important part the park played in the lives of his family and friends. His note prompted me to revisit the history tab on the Park Board’s page about Hi-View Park at minneapolisparks.org. (Every park has a history tab. I wrote most of them in 2008, but they are updated by park board staff as new developments warrant.)

In reviewing Hi-View’s history I was reminded of a tool the park board used to create or expand several recreation parks that are likely remembered as fondly as Etch remembers Hi-View. Landowners who don’t pay their property taxes eventually may forfeit their land. That land can be sold by the state or managed for “public benefit.” The Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners, as the Park Board was once officially called, acquired the land for Hi-View Park–free–under the public benefit provisions. I’ve cited below a section of the history of Hi-View Park, which I wrote for the park board’s website, that mentions other park land acquired through tax forfeiture.

“Hi-View Park was acquired from the state in 1950. The state had acquired the property for non-payment of property taxes. The original park was 3.74 acres, but was expanded by 0.12 acres in 1961 at a cost of $4,900. The park board acquired the land at a time when it was looking to fill gaps in playgrounds identified in a 1944 study of park facilities. While the neighborhood around Hi-View was not on the list of neighborhoods needing playgrounds, the park board seized the opportunity to obtain free land from the state, when it discovered the land was on the state’s list of tax-forfeited properties. The undeveloped land had been used as a playing field by children in the neighborhood for years.

The first instances of the park board seeking land on state tax-forfeiture lists was in 1905 when it acquired several lots to expand Glenwood (Wirth) Park and in 1914, when it acquired Russell Triangle. With the acquisition of four lots to enlarge Peavey Park and the acquisition of Northeast Field partly from the state’s tax forfeiture list in 1941, the park board began looking to the state as a source of cheap land.

In a matter of a few years after World War II, the park board acquired nearly all of Bossen and Perkins Hill parks and portions of McRae and Kenny from the state for no cost. The park board also eventually acquired part of North Mississippi Park from the state. By the late 1940s, the park board routinely scanned lists of land the state had acquired for non-payment of taxes and spotted the Hi-View land on such a list.”

I mention the acquisition of tax-forfeited land because it underscores the many creative methods used to acquire the land that became a celebrated and heavily used park system. Some parks are used primarily by neighborhood kids, others by people from across the entire city, state and beyond.

The park system is the result, in the end, of dedicated, persistent, efficient, and creative public servants. And it is still operated, managed, and adapted to our ever-changing needs and desires by the same type of praise-worthy public servants to whom we all owe a debt of gratitude. At the very least some respect.

David C. Smith

Cloggy’s Hockey at Sibley Field

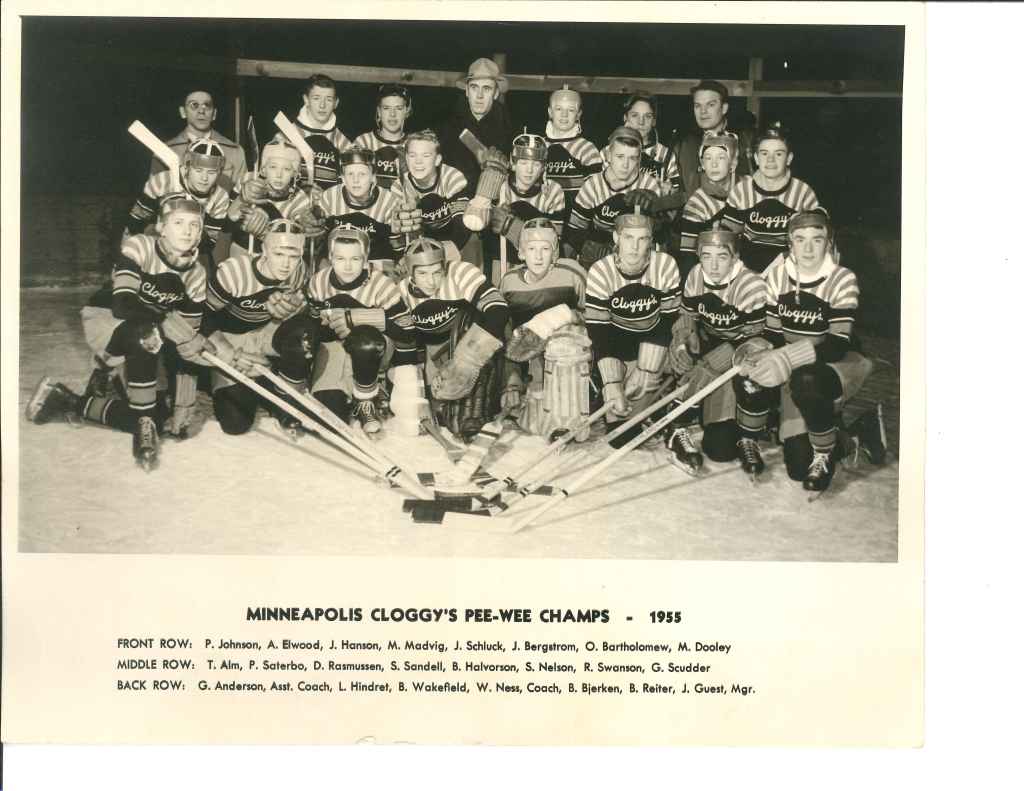

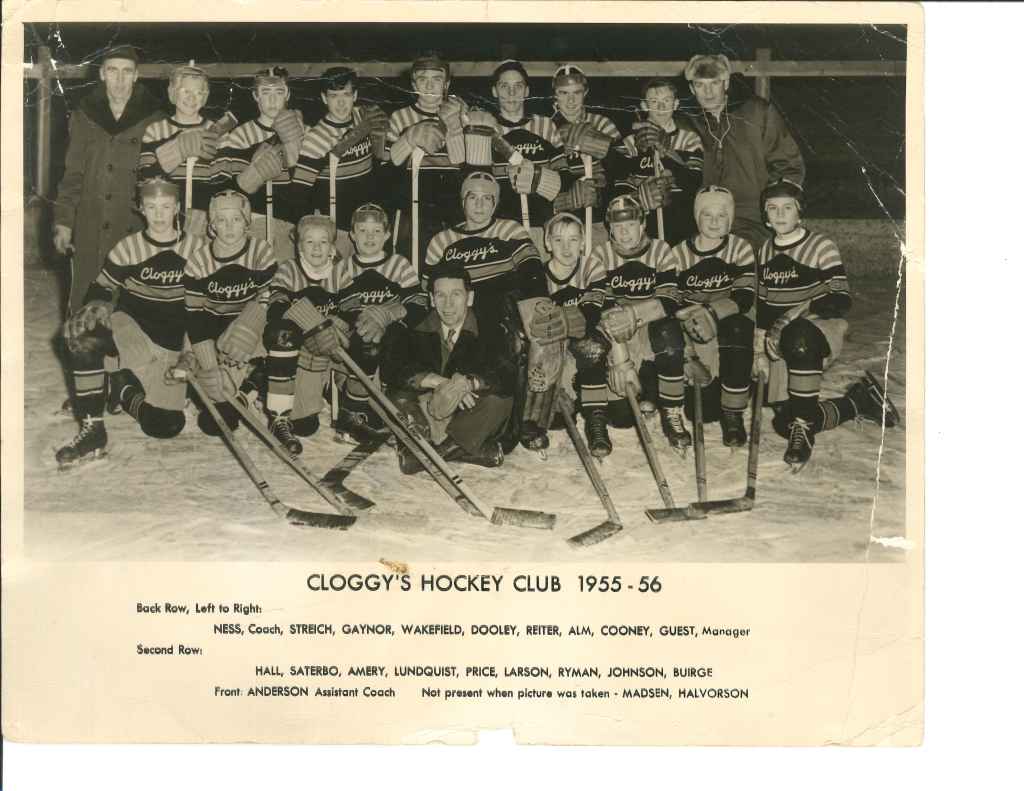

One of the most-commented on posts on this website was written nearly 15 years ago about Sibley Field, now renamed 40th Street Park. (Be sure to read the comments on that post.)

I can now add two excellent photos, with names, of more boys’ hockey teams sponsored by Cloggy’s Bar. I received a note this week from Ken Orum asking if I was interested in the photos that came from a collection from his grandparents James and Nettie Guest. James Guest appears in the photos as the manager of the teams. I presume these teams were based at Sibley Field too.

This was from a time when Minneapolis high schools produced excellent hockey teams, in part due to a vibrant playground hockey program. We don’t know the photographer or source of these images, but if anyone does, I’d be glad to provide further attribution.

Thanks to Ken Orum for providing the photos.

David C. Smith

The Fort Snelling All-Star Basketball Team

Today’s story is not about a Minneapolis park, but grew out of research into a basketball league run by the Minneapolis Park Board. Park league basketball, football and baseball games were for many years among the city’s leading sporting events.

—–

How a basketball team of Japanese Americans was assembled at Fort Snelling in the 1940s is a story of war, injustice, and patriotism. Why they were so good is beyond explanation.

Months before Pearl Harbor, the U.S. military knew conflict with Japan was possible and recognized that the U.S. would need people who could read and speak Japanese as an integral component of military intelligence. Where could the U.S. military find Japanese speakers? There were about 110,000 people of Japanese descent living along the west coast of the United States. So, in November 1941 the U.S. Army began to set up a Japanese language school at the Presidio in San Francisco. Barely a month later Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the U.S. and Japan were at war.

The plan to develop a corps of Japanese speakers and readers appeared prescient, but what followed made the job of military intelligence much harder. People of Japanese descent living on the West Coast were imprisoned. All of them. American citizens included. They were sent to ten hastily concocted prison camps that were deplorable in every respect — from concept to administration to location to construction. That meant of course that the hope to run a language school for Japanese American students in San Francisco was no longer possible. They had been scrubbed from the landscape.

The Army searched for another site for its language school. What it found was an abandoned Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps camp near Savage, Minnesota, a half-hour drive southwest of Minneapolis, and a governor, Harold Stassen, who was not afraid to have Americans of Japanese ancestry living and learning among his constituents. Minnesota did not have a history, as some western states did, of prejudice against Japanese. In fact, few Japanese had settled in Minnesota; the 1940 Census counted only 51 people of Japanese descent in the entire state.

Of course, that didn’t exempt those few from mistreatment in December 1941. Ed Yamazaki, who ran Ed’s Café on West Broadway in Minneapolis and lived in the leafy Linden Hills neighborhood was visited by police and agents of the Treasury department at work the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. They shut down his restaurant. He was allowed to open his restaurant again three days later, but his bank accounts were frozen and he was allowed to withdraw only $200 a month for living expenses. The same conditions were reported to have been imposed on a gift shop owner in St. Paul. These were apparently the only two businesses owned by persons of Japanese ancestry in the Twin Cities.

Perhaps someone feared that if they had spare cash laying around they’d send it to the Emperor. Yamazaki had lived in Minneapolis since 1914. His son had been a record-setting intermediate speed skater at Powderhorn Lake in Minneapolis before the war and was a U.S. Army Staff Sergeant at the time of Pearl Harbor. You couldn’t be more Minnesota than that. “We are sorry to see the war come,” Yamazaki said, “But what can we do? My family and I have no ties in Japan.”[1]

The Army’s task of developing Japanese language capabilities proved harder than initially imagined because the assumption that young men of Japanese ancestry would be able to speak their ancestral language was false. The Army was shocked to discover that only about 3% of the 3,000 Japanese-Americans already in the Army could speak their parents’ or grandparents’ language even a little bit. Despite that drawback, the Army still focused on the Japanese American community for students for the Japanese language program. Fortunately for the Army, although they and their families had been imprisoned because they were suspected, without evidence, of being potentially sympathetic to the enemy, many Japanese American men were American citizens and could be drafted into military service. Also fortunately for the Army, although their rights as American citizens had been suspended, thousands more Japanese Americans enlisted to fight for those rights for others.

The Military Intelligence Service Language School at Camp Savage opened in May 1942 but outgrew the outdated camp. In August 1944 the entire language school, about 1800 students at the time, was moved to Fort Snelling, a fort established in 1820 on a bluff at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers just south of Minneapolis. In all, 6,000 Japanese Americans went through the language school. (More than 30,000 Japanese-Americans served in the U.S. military during the war, including a division that fought with great distinction and suffered staggering casualties in Europe.)

The U.S. Army provided what recreational opportunities it could for the soldiers learning or perfecting Japanese language skills at the Fort, even though the demanding language courses of six to nine months duration left little time for recreation. Several sports were encouraged, basketball among them.

The Fort basketball players were good, so they entered a Fort “all-star” team in the top recreational basketball league run by the Minneapolis Park Board in January 1945. The highly competitive Park National league had for years featured the best basketball in the city, before the arrival of professional basketball and the Minneapolis Lakers. And even though the talent level had dropped during the war due to so many young men in military service, many excellent players still filled the rosters of the eight-team league. Especially big men. Players over 6’6” and those with bad knees, eyes or ears, even asthma, (maybe bone spurs) were exempted from service.

Many armed forces teams featured superb players during the war years and the Fort Snelling team was no exception. Still with a roster of men most of whom were well under six-feet tall — various newspaper articles calculated their average height at 5’6” — the success of the Fort Snelling team must have surprised local players and observers. All but two players on the team were of Japanese ancestry.

The leading scorer was Wataru Misaka. In a day when college basketball stars shined less brightly than today, Wat Misaka was a superstar. He would become even better known within a couple years. Misaka had starred for the University of Utah team that won the NCAA championship in March 1944 at Madison Square Garden and then defeated the National Invitational Tournament (NIT) champion, St. John’s University, on its home court in a playoff game to raise money for the Red Cross. Misaka and teammates won the hearts of New York City’s hard-core basketball fans in the process.

The day Misaka returned to Utah from New York to a hero’s welcome he also received his draft notice. Misaka had grown up in Ogden, Utah and like many other Japanese Americans in Utah, both in and out of internment camps, he ended up at the Fort Snelling language school. He was not the only player on that team with hoops cred.

Masaru Nishibayashi had played at Los Angeles Community College before he was imprisoned with his family at Denson, Arkansas. He was released from the camp to attend the University of Cincinnati where he played basketball for the Bearcats before entering the Army.[2] At 6’2” he was the tallest man on the team. He was also one of two players who played portions of the 1944-45 and 1945-46 seasons with the Fort Snelling team, because his language training was interrupted by attendance at Officer Candidate School in Georgia. He was one of the few Japanese Americans offered the chance to become an officer.

Another former college player on the 1945 team was John Oshida. He followed a most unusual path to Fort Snelling. He grew up in Berkeley, California where he was a star athlete. He was a freshman at the University of California when the war and imprisonment of Japanese Americans began, but he had a unique family connection.

When the Army began to put together a Japanese language program in San Francisco, one of the first hires as an instructor was a young man who had been born in the U.S. and graduated from Berkeley High School, but had returned to Japan for his college education at Meiji University in Tokyo. He, therefore, not only spoke and read Japanese as a native, but he was familiar with Japanese military terms and usage because, as all Japanese college students, he had been required to attend military training. He had worked most recently in the Japan pavilion at the Golden Gate International Exhibition. His name was Akira Oshida. He was John’s older brother.

When the MIS language school was established in Minnesota, Akira Oshida moved east to teach there and was able to get his brother out of the prison camp at Topaz, Utah and brought him to Minneapolis where he enrolled at Augsburg College in January 1944. John immediately joined the college basketball team, along with another Japanese American, Joe Seto, and became a starter for the Auggies.[3] Despite his unimposing wiry frame and wire-rimmed glasses, he had an immediate impact on Augsburg’s performance and created quite a stir in the state. A newspaper repeated a rumor, not true, that he had been a freshman basketball star at USC before the war. In the spring of 1944, he played doubles in tennis and shortstop and pitcher for the Auggies baseball team. He had pitched previously for the Post Office team at the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California in the summer of 1942. Tanforan was a horse racetrack near San Francisco where Japanese Americans lived in former horse stalls for several months until they were shipped to other prisons. Most were transferred to the bleak high-desert prison at Topaz, Utah.[4]

Sidebar: Ideals Never Lost

The Totalizer was a mimeographed newspaper produced at Tanforan Assembly Center by internees, many of them American citizens, who were held without rights or redress until they were shipped to one of ten prison camps. The editorial in the July 4, 1942 issue of the Totalizer contained these words: “The ideals which germinated in the birth of this nation as a free people are as valid today as they ever were. They still form the one bastion of man’s hope for a better world, unburdened of the weight of fascist tyranny. If we allow the apparent anomaly of our particular circumstances to tarnish our faith in the tenets of the democratic creed, we are divorcing ourselves from the current of humanity’s highest aspirations. In our observance of July Fourth, then, let us not speculate idly and fruitlessly on the special constraints and hardships—and, in many cases, the seeming injustices—which the fortunes of the present war have laid on us. Rather, let us turn our thoughts to the future, both of this country and of our place in it. It is our task to grow to a fuller faith in what democracy can and will mean to all men. To stop growing in this faith would be to abandon our most cogent claim to the right of sharing in the final fruits of a truly emancipated world.”

The sports columnist for the Augsburg College Echo, also a member of the basketball team, wrote, “Augsburg College as a whole, and specifically the basketball team, ran into some good luck this semester when Joe Seto and Johnny Oshida, two Japanese Americans from the West Coast, enrolled in Auggie Tech…Both of these likable fellas have proved their worth on the Augsburg basketball team.”

The Echo profiled Seto and Oshida as the first Nisei students to attend Augsburg. The profile noted that Oshida had a brother at Camp Savage as well as a sister in Hopkins. The writer encouraged students to talk with Oshida, “If you readers have any other questions about him, or his experience in the relocation camps, just ask him. He’s very willing to supply the answers.”[5]

Joe Seto became the sports columnist in the Echo the next school year and was also named honorable mention on the all-conference basketball team that year.

Another excellent player on the 1945 Fort Snelling team was John Okamoto. He was from the Seattle area where he was reported to have been an all-city high school basketball player at Broadway High School and was rumored, falsely, to have played for the University of California before the war. Okamoto, like Nishibayashi, played for the Fort Snelling team for two years because his post-language-school assignment was to the Fort Snelling HQ.

Only two of the 1945 Fort Snelling All Stars were not of Japanese ancestry. John Leddy was an especially valuable addition because he was six feet tall, providing a bit of height that the team lacked outside of Nishibayashi. Like Wat Misaka, he had the rare distinction of having played on an NCAA championship team, the 1942 Stanford team. While at Stanford he enrolled in an intensive Japanese language course and after joining the Army he was sent to an Army Japanese language program for officers at the University of Michigan for the 1943-44 academic year. Like many other military personnel enrolled in military courses at universities, he was eligible immediately to play basketball for Michigan. He earned honorable mention All-Big Ten that winter, along with teammates Elroy Hirsch, better known as future football Hall of Fame halfback “Crazylegs Hirsch” and Dave Strack who would later coach the great Michigan basketball teams of the 1960s.[6]

The other Caucasian contributor to the Fort Snelling team was Merle Gulick. Gulick had enrolled at DePaul to play basketball, where he would have been a teammate of George Mikan if he hadn’t been drafted into the Army. Gulick was from a famous family of missionaries to Japan and he had been born there and grew up speaking Japanese. He probably had a closer connection to Japan than most of his Nisei teammates. His great uncle was also the famous promoter of physical education in New York City, Luther Gulick. His father was the head of the new Japanese section of the OSS, wartime forerunner of the CIA, and after the war taught Japanese at the University of Chicago. While Leddy was often one of the top three scorers for the 1945 Fort Snelling team, along with Misaka and Oshida, Gulick was a less important contributor on the score board.

Little was known about Wat Misaka and his Fort Snelling team when it entered the top basketball league run by the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners in January 1945, least of all that they were studying Japanese in a secret military intelligence program. The purpose of their study — the entire Fort Snelling program — was not revealed until after Japan’s surrender and the war was over. The U.S. Army didn’t want Japan’s leaders to know that its written and spoken communications were being intercepted and understood. (Many American military communications in the Pacific truly were indecipherable as they were conducted by the famous Navajo code talkers.)

The clear favorite for the title of top amateur team in Minnesota in 1945 was a team sponsored by Ruff Bros., a chain of three grocery stores in Minneapolis. The captain of that team was Jerry Ruff, who had played college ball at St. John’s University in Minnesota. Led by former Gopher great, John Kundla, Ruff Bros. were undefeated in 1944 and many anticipated a similar performance in 1945 even without Kundla who had taken the coaching job at St. Thomas College in St. Paul. Ruff Bros. had won their first two games in the Park National season with ease, as had the Fort Snelling team.

When Ruff Bros. swamped the Citizens Club team 49-17 in the second week of play a Minneapolis Star sportswriter proclaimed that it “dispelled all doubt” that they were the team to beat in the city’s top league. But they would be beaten. A tight win by the soldiers over a team of Navy Flyers stationed at Wold-Chamberlain Airport set up a meeting between the two league leaders. The under-sized soldiers won easily, 46-35, snapping the “Ruffians” 26-game winning streak. Wat Misaka was the star, scoring 17 points. Throughout that season, the bigger the game, the more Misaka scored.

The Fort Snelling All Stars only lost a few games that season, one was to St. Mary’s College in Winona, which finished as runner-up in the forerunner of the Minnesota Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (MIAC). They also lost a rematch with Ruff Bros., which left the two teams in a tie for the city championship and set up a playoff for the title. Ruff Bros. won that playoff in a very close game. A three-point half-time lead was nursed into a 42-38 win. Ruff Bros. leading scorer that game was Gordy Flick, a 6’6” former Minneapolis South High School player who had also played at Drake University and for a couple of early pro teams in Wisconsin. The Fort Snelling All Stars, talented as they were, didn’t have answers for skilled players of that altitude.

News of the success of the Fort Snelling team spread to the prison camps. Prior to an Army tournament in Omaha, Nebraska, the Minidoka Irrigator, the newspaper of the Hunt, Idaho prison camp, where 10,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned, ran a story about the team. It was written by Pvt. Peter Ohtaki, a Fort Snelling language student who had been imprisoned previously at Minidoka.

During that season a group of Fort Snelling players travelled on furlough to visit families and friends at the Topaz, Utah prison. While there they played a team of Topaz all-stars. The Fort Snelling players won, but barely, 53-49, suggesting the popularity of basketball and the high skill level in the Japanese American general population. Johnny Oshida and Kenji Hosakawa led the Fort Snelling players in scoring that game.[7]

The following winter the Fort Snelling team was much more visible in the basketball community not only in Minnesota, but Wisconsin, perhaps because the war was over and the Japanese Army had been defeated. It is unclear whether the brass at Fort Snelling or the U.S. Army encouraged greater visibility for the Fort Snelling All-Stars, or if, with the war over, there was less academic pressure on the remaining Japanese language students at the Fort. Whatever the reason, the team embarked on a much more rigorous schedule in the 1945-46 season.

The Fort Snelling Bulletin, the Fort’s weekly newspaper, noted in December 1945 that the team would play a tough schedule on the road but was also entering the city park league again just so others at the Fort would have the opportunity to see them play in town. Except for Nishibayashi, who would only play in a few games before he departed Fort Snelling, and Johnny Okamoto, who would play the complete 1946 season, the entire team was new. Gone were the former college stars, but the Fort Snelling language program still put a very good team on the floor. Okamoto took over the scoring burden from Misaka, Oshida and Leddy. He was backed up by Dan Fukushima, Joe Kadowaki, and George Mizuno among others.

Fukushima was another kid from Berkeley who had reportedly played basketball at Fullerton Junior College. Mizuno was singled out in coverage of Fort Snelling games for his speed and his diminutive stature; he was listed as 5’5.” Kadowaki was called “Big Joe’ in the Fort Snelling Bulletin and described as “hefty, but speedy,” so “big” may not have implied “tall.” Before the war, Kadowaki played for Santa Ana Junior College. Kadowaki was one of the few Fort Snelling players who had served in the famous 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an all-Japanese American unit that had fought with distinction — and suffered one of the highest casualty rates of any American unit — in Italy and France.

The Fort Snelling team played its best game of the year, according to the Bulletin, in the opening round of the U.S. Army 7th Service Command annual tournament in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The Fort Snelling team defeated the tournament favorite from Fort Leavenworth. Fort Snelling lost its next game, however, knocked out of the tourney by the host team from Fort Warren, which was where the Army trained its Quartermaster Corps. Fort Warren featured a 6’6” center who played before and after the war for teams in the early National Basketball League and a 6’3” forward who would become a college star in Indiana after the war. They put the Fort Snelling team at a height deficit, once again, that it couldn’t overcome.

The 1945-46 team played fifty-one games and lost only ten. It split two games with Eau Claire Teachers College and lost in overtime to St. Cloud State College. Both college teams won their respective conferences, which won them invitations to the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball (NAIB) national tournament in Kansas City. St. Cloud was defeated in the second round by Indiana St., which wasn’t beaten until the national championship game.[8]

Those Fort Snelling losses, like most of their wins, were played on the road. On many weekends the team played four games, usually playing an afternoon and evening game on Sundays. They travelled from southern Minnesota to central Wisconsin to the Iron Range in northern Minnesota. The Fort Snelling team would take on local stars with the money raised from usually sold-out arenas going to some sponsoring charity. Receipts from Fort Snelling games went to everything from the local library fund in Cornell, Wisconsin to the American Red Cross and National Infantile Paralysis Foundation.

The team was nearly universally well-received by local crowds according to newspaper accounts. Of the dozens of articles in Minneapolis newspaper sports pages the team was never called Japanese American and was referred to even as Nisei only occasionally. The team was almost always called the “soldiers” from Fort Snelling. The same was not true for all smaller-town newspapers, which often wrote about the “Japanese American” or “Jap-American” team, although the term appears not to have been used with pejorative intent.

One of the few newspaper references to prejudicial treatment of Fort Snelling athletes came in an article from the Winona Daily News which, when reporting on a local baseball game featuring a team from Fort Snelling, noted that fans had shown “above average respect for the soldier nine. Only once did anyone remark about the nationality of the visitors and he was reported to be somewhat under the influence of liquor.”[9]

The Fort Snelling Bulletin, admittedly not an unbiased source, claimed that the Fort Snelling team was one of the “most popular” and “most respected” teams in the area. Most coverage of their games outside of Minneapolis referred to enthusiastic, over-flow crowds. Their overtime loss to St. Cloud State, for instance, was played before “a shrieking capacity crowd” which witnessed “one of the most exciting games ever played in St. Cloud” featuring the “sharpest shooting show” in years.[10]

A team of Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin all-stars lost to Fort Snelling when, trailing 63-59 with 30 seconds on the clock, the soldiers stole the ball three times and John Okamoto hit three long shots, the last one at the buzzer, to win 65-63. The Chippewa Falls coach told a Bulletin reporter, “You guys are like the Globe Trotters. You can win anytime you want to and stage a close finish to give the spectators a thrill.” He said he was glad the Fort Snelling team didn’t “pour it on” because the fans like to see “a close game with the home team in the running.”

Once again, the Fort Snelling team finished second in the top Minneapolis park league behind many of the players who had played for Ruffs along with several military veterans who had been wounded and discharged from service.

The Fort Snelling All Stars finished their season in mid-April of 1946 with two two-point wins in front of overflow crowds in Buhl and Crosby-Ironton, two basketball hotbeds on Minnesota’s Iron Range. That was not the end of basketball in the lives of the Japanese language students at Fort Snelling, however.

After serving as translator with the U.S. military administration in occupied Japan, Wat Misaka returned to the University of Utah for the 1946-47 season to complete his degree and his basketball eligibility. Utah once again made it to Madison Square Garden in the post-season, this time in the prestigious National Invitational Tournament (NIT). Utah defeated Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky Wildcats in a monumental upset — they were 11-point underdogs — in the championship game largely because Misaka held Kentucky’s leading scorer and All-American, Ralph Beard, to a single free throw, nearly twenty points below his average. One writer said being covered by Misaka was like “getting into a beehive.”

Misaka was so impressive, and so admired by New York basketball fans, that in the spring of 1947 the New York Knicks selected Misaka in the first round of the pro basketball draft.[11] Later that year, Misaka became the first non-white player in league history.[12] Misaka was cut by the Knicks several games into the season and many believed he wasn’t given a fair chance partly because of his ancestry. He toured for a time playing against the Harlem Globetrotters, but turned down an offer to join the Globetrotters from owner Abe Saperstein in order to return to school and get an engineering job.

Both John Oshida and John Okamoto remained prominent in Japanese American basketball circles. In the mid-1950s when a columnist for Shin Nichibei, a Los Angeles newspaper serving the Japanese American community, selected a Nisei basketball All Time Dream Team he picked Johnny Oshida as one of his guards.[13]

Oshida’s postwar prowess was highlighted in a report of a Japanese American basketball tournament in Chicago in 1949. The Chicago team beat Berkeley for the title, but high scoring honors in the game went to a Johnny Oshida of Berkeley with 17. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that most of the players in the tournament were veterans of the war.[14]

The leader of the champions from Chicago was Oshida’s former teammate at the Fort, John Okamoto. Okamoto became a prominent player and coach in Japanese American basketball circles in Chicago. He led his Chicago team in scoring in the 1954 Nisei North American tournament won by a Toronto team.

One of the leaders of the 1946 Fort Snelling team, Dan Fukushima, became a well-known high school basketball coach in the San Francisco Bay area after the war, a leader of the California Basketball Coaches Association, and 1973 National High School Basketball Coach of the Year while coaching at James Lick High School in San Jose. He had also been chosen as teacher of the year in the San Jose school system in 1967.[15]

A team of players with Japanese ancestry never entered the annual All-Nations Basketball Tournament at Pillsbury House in Minneapolis, but the soldiers team of 1946 came close. That prestigious tournament featured teams of different national heritages and was played every year from 1929 to 1959. The Fort team planned to enter the tournament representing Japan, but a scheduling conflict with an Army tournament prevented them from competing. Despite missing that tournament, the Japanese American players from the Fort had already established their basketball bona fides on the “Pill House” floor by their success over two seasons playing in the city’s top amateur league run by the Park Board.

The 1950 census revealed that more than 1,000 Minnesotans claimed Japanese ancestry, a twenty-fold increase over 1940. Evidently, some Japanese Americans who came to Minnesota to study or teach at Fort Snelling stayed after the war.

[1] Minneapolis Tribune, December 9 and 12, 1941.

[2] Manzanar Press, March 18, 1944. Manzanar was a prison camp in California — one of ten in the U.S. — where Japanese citizens were imprisoned from 1942-1945.

[3] Blickstad, Paul, Augsburg Echo, February 11, 1944.

[4] Tanforan Totalizer, July 4, 1942. Whoever wrote that is a better person than I.

[5] Augsburg Echo, March 24, 1944.

[6] Minneapolis Star, March 7, 1944.

[7] Minidoka Irrigator, February 17, 1945. Topaz Times, February 21 and 24, 1945.

[8] Fort Snelling Bulletin, April 12, 1946.

[9] Winona Daily Times, September 19, 1945.

[10] St. Cloud Times, January 29, 1946; Fort Snelling Bulletin, February 2, 1946.

[11] The Knicks at the time were in the Basketball Association of America (BAA), which the National Basketball Association (NBA) considers its predecessor and incorporates BAA history into its own.

[12] Transcending: The Wat Misaka Story, a documentary film by Bruce Alan Johnson and Christine Toy Johnson, 2008, ReImagined World Entertainment. The film tells the story of Misaka at the University of Utah and the New York Knicks but overlooks his time as a star for the Fort Snelling All-Stars on Minneapolis’s hardwood courts.

[13] Shin Nichibei, February 15, 1955.

[14] Chicago Daily Tribune, November 28, 1949.

[15] Los Angeles Times, August 1, 1987; Joel Franks, Crossing Sidelines, Crossing Cultures: Sport and Asian Pacific Americans,

David Carpentier Smith

Park Puzzlers: Wirth, Gross and Minnehaha

Metal objects have been found in three places which have puzzled people. What are they? Do they serve park purposes?

Michael Fleming asked a question I can’t answer. Maybe one of you can. He sends these two pictures of metal posts in Theodore Wirth Park across Golden Valley Road from the Golden Valley Fire Station near the intersection of Bonnie Lane.

If you know what these are, leave a comment.

I also found another marker on park land similar to the one described by Craig Johnson in a post a few years ago. This marker was found along the sidewalk on the west side of Gross National Golf Course in St. Anthony, presumably on another park boundary. Gross is one of three golf courses owned and operated by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board (MPRB) that are wholly or partly outside of Minneapolis city limits. The others are Wirth and Meadowbrook. A fourth golf course operated by the MPRB outside of city limits is on leased land at Fort Snelling. (The park board is the only Minneapolis government entity allowed to own land outside of city limits, which is also why the park board owned and developed the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport from 1926 until the Metropolitan Airports Commission was created by the legislature to operate the airport in 1943.)

Finally, Rene Rosengren sent another picture of old machinery near the dog park at Minnehaha.

Based on the information Rene provided, I am quite certain that this is on former Bureau of Mines land and not part of Minnehaha Park. I think it unlikely that this was left behind by limestone quarry work in the park and was part of Bureau of Mines project.

If you have other ideas or can identify these objects, we’d like to hear from you.

David Carpentier Smith

Minnehaha Rails

Rene Rosengren recently sent some photos of metal rails she found south of the Minnehaha Off Leash Dog Park just off the Minnehaha Trail. Any ideas what they are?

I’ve written about the limestone quarry at Minnehaha Park that was operated for just one year by the park board in 1907, but was reopened by the WPA from 1938-1942. I think these tracks are too far south to have been part of that quarry, but the narrow gauge suggests that they were part of a quarry or similar extraction enterprise.

I suspect the tracks were once a part of the Bureau of Mines Research Center on federal land that is now owned by the National Park Service as part of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area.

Rene and I would be happy to hear any thoughts on the narrow gauge tracks.

David Carpentier Smith

Big Island, Big Book

Just in time for the history buff on your gift list comes a big book: The History of Big Island, Lake Minnetonka. While the book is richly illustrated with historical photos and drawings, it is much more than a coffee-table book. It appears to be a labor of love by author Paul Maravelas: exhaustively researched, carefully written, and extensively footnoted.

Maravelas covers the entire recorded history of the island–and the lake–drawing from archaeological records, oral histories, journals, letters, newspapers, and official records. He takes the reader through the many purposes the island has served from maple sugar production and wild rice harvesting to farming to amusement park and campsite.

I especially appreciated chapters on what we know of the Dakota use of the island and, years later, the creation of an amusement park on the island and the role played by the streetcar line from Minneapolis. Of course, many of the names that fill accounts of Minneapolis park history pop up in the history of settlement and development at Lake Minnetonka and Big Island, too. As the source of Minnehaha Creek, Lake Minnetonka will always be off interest to many Minneapolitans, although the watershed isn’t the book’s focus.

I would expect everyone who lives at or near the lake would want this book in their library along with all of us city dwellers who appreciate local history and enjoy a good story.

The book is available from Minnetonka Press. Free shipping via USPS media mail is offered on the publisher’s website this month, which is a significant value as the book runs 470 pages and weighs 4 1/2 pounds. As I said: Big Island, Big Book.

David C. Smith

After Careful Consideration: Horace W. S. Cleveland Overlook

The man who first suggested putting Horace William Shaler Cleveland’s name on something in the Minneapolis park system was William Folwell, the president of the Minneapolis Park Board in 1895. Folwell noted in the annual report of that year that due to Cleveland’s advanced age, then 81, he was no longer able to assist in the development of park plans. Folwell then recommended, “In some proper way his name should be perpetuated in connection with our park system.”

Last week the Minneapolis Park Board acted on Folwell’s advice and named a river overlook near East 44th Street on West River Parkway the “Horace W. S. Cleveland Overlook.”

Cleveland was already 58 years old when he was invited to come to Minneapolis from Chicago to give a public lecture at the Pence Opera House on Bridge Square in 1872. He spoke on how to improve the city through landscaping. He was a big hit and his advice was sought in St. Paul and Minneapolis on how to improve the cities. He wrote an influential book based on his lectures, Landscape Architecture as Applied to the Wants of the West. That began his association as an influential advisor to both cities. When the Minnesota legislature created the Minneapolis Park Board in 1883, one of its first acts was to hire Cleveland to give his advice on what needed to be done.

He produced a report complete with a map, which he called Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis. His map showed a continuous parkway connecting Lake Harriet with Loring Park, then north to Farview Park, directly east past Logan Park in northeast Minneapolis, then south back to the Mississippi River Gorge near the University. His parkway continued on both sides of the river from Riverside Park out to Lake Street and then all the way back west to what is now Bde Maka Ska. It was the brilliant original imagining of what would become the Grand Rounds. It helped instill the notion that parks are not isolated parcels of land but form a part of a “system” that is integral to the quality of life and well-being in a city.

Cleveland had seen the struggles of older Eastern cities such as Boston and New York to create parks in already crowded urban areas. He had worked in the park system in Chicago and saw the same struggles to create open spaces in built environments. He had long argued in Minneapolis and St. Paul to create parks while undeveloped land could still be acquired at reasonable cost and features of natural beauty could still be preserved for public enjoyment. That we have such wonderful open spaces and preserved nature in our cities today owes much to Cleveland’s vision.

It is especially appropriate that an overlook of the river gorge be connected with Cleveland’s legacy. He had an affection and admiration for the beauty of the unique river gorge above all other of “nature’s gifts” to Minneapolis and St. Paul. He argued eloquently for the preservation of the natural riverbanks, calling the heavily wooded, still-unscarred river gorge a setting “worthy of so priceless a jewel” as the mighty river. Both St. Paul and Minneapolis heeded his advice.

The setting is still worthy of the jewel. Even though most of the color is gone from the wooded river banks, you might want to visit the Mississippi River overlook. Or at least cross over one of the river bridges and marvel at the beauty that has been preserved in part due to the vision and persistence of Horace William Shaler Cleveland, which is finally properly acknowledged.

David C. Smith

Between Wirth Par 3 Golf Course and Twin Lake: What’s the Story?

I recently received a question from a reader that I can’t answer, so I thought maybe someone else could. I am not a golfer and I have never explored the area west of the Wirth Par Three golf course. Here’s the question:

“I am wondering if you know any of the history about a seemingly out-of-place beautiful meadow/clearing just west of the 3rd hole of the Theodore Wirth Par 3 golf course. You cannot see it from the golf course but it’s easily accessible by the trails in the area.

Nestled in the meadow is a grass trail with remnants of an old asphalt trail in a tiny section, which makes me wonder if the area has an interesting “lost” history. A bit further west within those woods are remnants of an old wooden staircase built into the hillside leading down to Twin Lake. I speculate that over 50 years ago that it might have been a popular swimming area for Minneapolis residents.

Any information you may have on that meadow, as well as the history of the staircases down to the lake would be very intriguing.”

Thanks, Derek. If anyone can shed light on the landscape there and its history, please jump in. Any memories of the place?

Did you know that at it’s largest Theodore Wirth Park, previously Glenwood Park, was bigger than Central Park in New York? Park acreage was reduced when Highway 12, now I-394, cut off the southern part of the park. Part of the land south of the highway was sold to The Prudential Company for an office building in the 1950s. That was the largest ever loss of Minneapolis park land in one chunk, although the Ford Dam flooded many acres of park land along the river in the 1910s and freeway construction sliced off pieces of parkland in all parts of the city since the 1960s.

David C. Smith

Derek sent the following photos to illustrate the meadow and path. Thanks!

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment