Archive for the ‘Wold Chamberlain Field’ Tag

Baseballs at War

Once in awhile I come across a little gem of info that I don’t know what to do with because it’s not about Minneapolis parks, but is too interesting to let slip back under the covers of history. So this…

From the Minneapolis Tribune, Thursday, February 7, 1918, dateline New York, in its entirety:

Baseball To Follow The Flag In France

There is a probability baseball will be played extensively by the troops in France this spring. The Y.M.C.A. war work council has awarded a contract for 59,760 baseballs, probably one of the largest orders ever placed. Special preparation has to be made in packing these balls so they will not be affected by dampness. Special cases are made for the purpose.

I looked to see if I could find an image of a 1918 baseball online that I could post here and I found two noteworthy images.

The first was a 1918 baseball for sale at the time of this writing on eBay. The names of soldiers, complete with rank are printed on the ball. I don’t know if this was one of the balls sent to France by the “Y”, but it was clearly well-used. I love the red and blue stitching. I wonder if it was so tightly wound—or juiced—that it could leave a ball yard at an exit velocity of well over 100 mph as they do at Target Field these days. Doubtful.

This 1918 baseball signed by soldiers, complete with ranks, is for sale on eBay by showpiecessports. The linked page above includes seven more photos of the ball. Thanks to showpiecessports for permission to use their image.

I also found another image at the National Baseball Hall of Fame that tells more of the story of baseball and WWI. This photo suggests that the ball used by the soldiers was the same—red and blue stitching—as that used by Major League Baseball. One notable change in the game since 1918 is immediately obvious: game balls weren’t discarded then after they had hit the dirt once!

One panel of the ball reads, “Season ending on Labor Day on Account of War.” The other, “Last ball used in game at Navin Field. Hit by Jack Collins off Bobby Veach. Caught by Davy Jones.” For Bobby Veach, who led the American League in RBI that year as an outfielder, this was the only pitching appearance of his 14-year career. Thanks to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for permission to publish this image. (Milo Stewart, Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

The excellent article that accompanies this photo tells of how baseball players were viewed as potential soldiers in the Great War. Quite different from WWII. The full story of the game and the season from which this ball was saved—101 years ago this month—is fascinating. A little of everything: Star Spangled Banner, Ty Cobb, rifle drills, the Boston Red Sox winning a World Series before Big Papi, and more.

With all those YMCA baseballs going to France in 1918, I’m surprised the French didn’t pick up any interest in the game, but they seem not to have. I suppose when part of your country is reduced to sticks and mud and cemeteries, you don’t have much time to think about new sports played on fields of grass.

The American monument to soldiers–some of whom may have played with those YMCA baseballs–who died near Chateau Thierry in WWI. Not many miles from this sobering, beautiful monument is where Ernest Wold and Cyrus Chamberlain, two young men from Minneapolis, died as aviators in the war. The Minneapolis airport, owned by the Minneapolis park board from 1926-1943, was named Wold-Chamberlain Field in their honor. (Photo: David C. Smith)

Baseball and war brings to mind the mistaken perception that baseball was spread in the other direction, to Japan, by American soldiers after WWII. Baseball was popular in Japan decades before then.

The University of Chicago’s baseball team played the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis in August 1910 on their way to the West Coast for a trip to Japan to play Japanese university teams. The next spring a team from Japan’s Waseda University—which had hosted the U of Chicago team—played two games against the Gopher nine at Northrup Field and Nicollet Park, losing 3-2 in 15 innings and 8-2.

The Tribune reported that the Chicago team—and a University of Wisconsin team in 1909—had been treated as “national guests” of Japan and noted that special arrangements were being made to entertain the Waseda University team “so they will feel they are the guests of the Twin Cities as well as the university.”

I have not found any similar stories about teams from the Sorbonne in Paris looking for games with local nines.

The Minneapolis park board did not create its first baseball field until 1908. Before then, sports fields were not viewed by many people as legitimate uses of public park land.

I wonder if we’ve sent any baseballs or baseball fields to Afghanistan? You’d think we might have after nearly two decades of war there. On the other hand we’ve had military bases in Germany for more than 70 years and only Max Kepler to show for it baseball-wise. Taking nothing away from Kepler; I hope he’s healthy for the Twins in the play-offs.

David Carpentier Smith

“The Yard” — or Downtown East Commons: A Caution from Minneapolis Park History

Hurrying to create a park in “The Yard” (since renamed the “Commons”) between downtown and the new Vikings stadium could result in disaster, if the history of Minneapolis parks provides any lessons. The greatest land-use mistakes in Minneapolis park history came from creating parks for purposes other than the relaxation, recreation, entertainment or edification of its citizens. Creating grounds for a pleasant stroll to a stadium eight days a year isn’t reason enough to make “The Yard” work as a park. Planning for those two blocks has to go well beyond landscaping only for the benefit of surrounding property owners, too.

An Expensive Failure: The Gateway

On four notable occasions, the park board has created parks largely for other than “park” reasons. The first, and still most-disastrous, was the creation of The Gateway in 1913 at the junction of Hennepin and Nicollet Avenues just west of old Bridge Square approaching the Hennepin Avenue Bridge. The triangular park was created to be an attractive “gateway” from the railroad station into downtown. The welcome intended for visitors, or travellers returning home, was clear from the words carved in stone on the pavilion at The Gateway:

“More than her arms, the city opens its heart to you.”

That slogan must have sounded less smarmy to 1913 ears than it does to mine. Parks, as well as slogans perhaps, were still on experimental footing in the “new” cities of the American west and The Gateway was the first venture of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners into downtown Minneapolis.

The buildings razed to make room for the park reportedly housed 27 saloons, which for many park advocates was reason enough to create the park. But neither open heart nor closed saloons were enough to make the park successful.

The Gateway 1918 at the intersection of Nicollet Avenue (left) and Hennepin Avenue (right). The Mississippi River and Hennepin Avenue Bridge are behind the photographer, Charles P. Gibson. (Minnesota Historical Society)

By 1923, the park board was spending more than 5% of its annual citywide operating budget on the park, mostly on park police patrols, because, in addition to the city’s arms, the park board had opened toilets – er, “comfort stations” – in The Gateway’s pavilion. The park quickly became a favorite hangout for lumbermen between jobs, as well as the unemployed, indigent or inebriated. What was supposed to get rid of ugliness and beautify the city, became an eyesore itself.

This infamous 1937 photo may overstate the case, but it does suggest one typical use of the park. Notice however that there are no nappers across the street, on the block that holds the pavilion and fountain. (Minneapolis Star Journal, Minnesota Historical Society)

Despite an attractive pavilion and a fountain donated by Edmund Phelps (now in Lyndale Park near the Rose Garden), the park served too few constituents (or at least some the city thought undesirable) and little park purpose beyond decoration. The park was controversial even when it was built, with such thoughtful park observers as former park commissioners William Folwell and Charles Loring opposing the park. Loring’s wife owned some property condemned for the park, but nonetheless he predicted correctly that it would become a home for indigent men. (See Florence Barton Loring’s reflective response here.) The pavilion was closed and leveled in 1953 and the fountain was removed to Lyndale Park in 1963, when the old Gateway ceased to exist. (For the rest of The Gateway story go here, then click on “Parks, Lakes, Trails…”, then “Gateway” in the index.)

Fenced. Desolate. Doomed. The Gateway in July 1954 after demolition of the pavilion, looking toward the river from Washington Avenue. (Minneapolis Star Journal Tribune, Minnesota Historical Society)

The Gateway was by far the most expensive park built during the first thirty years of the Minneapolis park board’s existence. The total cost was nearly one million dollars, more than had been paid to acquire Lake Harriet, Lake Calhoun and Lake of the Isles – plus parks and parkways along both sides of the Mississippi River – combined!

A Huge Success: Wold-Chamberlain Field

The next time the park board was asked to build something for the city turned out quite differently. When Minneapolis needed an airport, the park board was the only municipal entity that could legally own land outside city limits. Therefore, it fell to the park board in 1928 to own and operate the municipal airport on the site of the old motor speedway next to the Fort Snelling military reservation. The park board operated and developed Wold-Chamberlain Field, built it into a respectable airport, and turned it over in the mid-1940s to the newly created Metropolitan Airport Commission. Chalk one up to collaboration among city, park, civic and business interests. The goals, however, were clear, unambiguous and limited – and in the 1920s the airplane was still little more than a curiosity. Few people anticipated the future importance of flying machines and places to land them.

Wold-Chamberlain Field, Minneapolis’s airport, 1941. The passenger terminal is lower right. Owned and developed by the Minneapolis park board, 1926-1943. One of the only success stories when the park board was asked to develop something other than a “park.” (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

A Second Downtown Disaster: Pioneer Square

The next effort at collaboration was much less successful. Like The Gateway, it was downtown. Another cautionary tale. The U.S. government wanted to build a new post office in downtown Minneapolis in 1932, but asked that a proper setting be provided for the building on the west bank of the river just above St. Anthony Falls – a stone’s throw from The Gateway, which was already admittedly a failure as a park. In the grip of Depression, however, the city needed the jobs and the federal money that would be spent, despite what seem to have been the obvious warnings of The Gateway experience.

Dedication of Pioneer Statue in Pioneer Square in front of the post office, 1936. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

The city asked the park board to build a post office park, but the park board demurred until the city agreed to finance most of the land acquisition instead of having the park board assess property owners. Enough money was left after land acquisition, demolition and improvement to commission a sculpture for the park, which depicted pioneers. Despite the sculpture (now in B.F. Nelson Park) and the attraction of a new, immense post office, Pioneer Square soon followed the path of The Gateway. According to Charles Doell, park superintendent in the 1950s, after the snow melted at the end of the winter of 1953, maintenance crews picked up 70 bushel baskets of empty wine and whiskey bottles from The Gateway. One Monday morning in the summer of 1953, crews picked up 62 empty wine and whiskey bottles from the grass at Pioneers Square. (Charles E. Doell Papers, Hennepin History Museum). Further proof that you can’t just plop green space down in a city and expect it to serve some vague “beautifying” or “park” purpose – even with some dressing up. Pioneer Square also fell to urban renewal in the 1960s. (Read more about Pioneer Square and other “lost” Minneapolis parks here.)

A Drainage Ditch

The fourth instance of the park board acquiring a park for non-park reasons occurred in the far north of the city. The low land around Shingle Creek north of Webber Park often flooded, so was unusable for development. Due to a critical housing shortage for returning soldiers and sailors and their new families after World War II, the city asked the park board to acquire Shingle Creek – from Webber Park to the northern city limit — and lower the creek bed to drain the neighborhood so homes could be built there. The park board very reluctantly complied with the city’s request, even though the park board had higher priorities elsewhere. The effort succeeded in creating new housing lots, but has contributed little to the overall park experience in the city. Creekview Park is certainly a positive in the neighborhood despite its location only a few blocks from Bohannon Park, but Shingle Creek, in places, still resembles what you’d expect of County Ditch Thirteen. (I think Shingle Creek could and should be made a more valuable park resource.)

The Yard. Somewhat off topic, history suggests the advisability of a different name than “The Yard.” It’s kinda folksy and cute, but Minneapolis has twice tried “The (Something)” and both were trouble. (Try writing about them or describing them and you’ll see.) The Gateway and The Parade, both official names, were inevitably shortened to Gateway and Parade. Those two words were distinctive enough to stand alone without creating confusion, at times, but “Yard” isn’t. Whose Yard? Not to mention connotations of prison and the Hennepin County Jail overlooking it. The name may have served Vikings or Wells Fargo or Ryan or Rybak’s marketing efforts, I don’t know its origin, making the place sound homey, as if it was “our” space, personal space, but it has severe limitations for daily usage.

Of these four cases of park building for non-park reasons, the two parks created downtown, The Gateway and Pioneer Square, stand out as dismal and expensive failures. They were built strictly to provide a more attractive setting for other activities and buildings. I’m afraid that is all that the Downtown East Park or “The Yard” is now. And if that is where the discussion remains, it will fail as a park and become an eyesore, a headache or both. Who will go there, why will they go there, what will they do there? What use will be made of the space, what traditions will be shaped there, what memories will be recorded there? If the answer doesn’t involve more than eight Sundays a year, it is the wrong answer. And this is not Chicago, New York, Palo Alto or Cambridge, Mass. It is Minneapolis, which already has parks, lakes, river, streams – and history. Don’t give us someone else’s park and expect it to work.

David C. Smith

© 2014, David C. Smith

A Racetrack Before It Became a Park — and an Airport

Not many people would recognize this Minneapolis park property, which lies outside city limits and was acquired in 1928, twelve years after this photo was taken. There is some uncertainty about how much of this property is still technically owned by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board, but the property is administered by another agency.

This is the famous Twin City Motor Speedway, or Snelling Speedway, in 1916, the second year of its three-year life. The speedway was named informally for its location adjacent to Fort Snelling. The infield of the two-mile concrete track was later used as a landing field for airplanes — and eventually became Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport. The Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners acquired the land in 1928 to develop it as an airport for the city. The task fell to the park board because it was the only agency of Minneapolis city government that could own land outside of city limits. (The law that permitted the park board to own land outside city limits was passed by the Minnesota legislature in 1885 to permit the park board to purchase land in Golden Valley for part of what eventually became Glenwood (Wirth) Park .) The park board built and ran the airport from 1928 until the Metropolitan Airports Commission was created in 1943, at which time the park board turned over administration of the airport. The park board had spent a significant percentage of its meager resources in those years developing the airport.

The enormous grandstands pictured left and center were built in 1915 to hold 100,000 people. The problem was that far, far fewer attended the few races held there. The first major race in 1915, a 500-mile race patterned after the Indianapolis 500, was widely promoted by the newspapers for weeks. The weekend of the race — the first weekend in September, just before the State Fair opened — the Minneapolis Tribune wrote that hotel rooms were impossible to find in the Twin Cities; hoteliers were referring unaccommodated visitors to private homes for a place to sleep. It was said to be the busiest weekend in the history of Minneapolis hotels with guests arriving from around the country. The Twin City Rapid Transit Company built a special spur track to the speedway to transport the crowds.

Unfortunately for the promoters, drivers, and the legions of workers who constructed the track and were not paid, attendance was much smaller than hoped. Society columns in the Tribune covered the rich and famous who attended the races and trumpeted this “innovation in divertisement” for the social elite, but the paper reported race attendance at only 28,000.

The 1915 race was a disappointment in every respect. The banked concrete track, heralded as the fastest and safest track in the world, was in fact extremely rough. The cars vibrated to pieces and the drivers didn’t fare much better. The champion Italian driver, Dario Resta, was reported to have denounced the roughness of the track “vociferously” after his first test drive during race week. If you know any Italian curse words, you could probably translate the “vociferously”. He was prescient, because his car didn’t survive much more than 100 miles on race day. But potential race fans didn’t know that ahead of time.

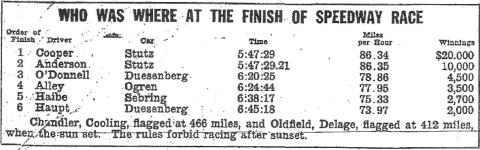

Neither could they have imagined the snoozefest that the race became. It only takes a glance at the race results to understand how tedious the day must have been for spectators. With only twenty cars starting the race and most of them falling apart or dropping out for mechanical reasons early on — having a “mechanician” riding along, the second person visible in the cars, didn’t prevent mechanical failures — there wasn’t much action despite the nail-biting finish of the race, which was won by 1/5 of a second. The Tribune, which had promoted the race so breathlessly, could hardly contain its excitement proclaiming in its headline Sept. 5, 1914, “Cooper Wins Closest Finish in History.”

An exciting finish didn’t make up for the rest of the race. The slow pace of the race, only 86 mph, dragged it out for nearly six hours, and the third place car was more than a half-hour behind the leaders. The Tribune blamed the pace on the fact that the cars of so many of the “most daring” drivers — “speed demons” — were incapacitated. Those drivers included the famous Italians Resta and Ralph De Palma and the American “Wild” Bob Burman. Picture only eight cars spread over a two-mile track, none of them travelling much faster, and some not as fast as, ordinary traffic on 35W and think of what you’d be doing to amuse yourself as a spectator. As stirring as the finish must have been with Cooper and Anderson pushing their matching Stutzes to the finish (the Stutz company dropped racing the next year anyway), most of the barely awake spectators headed for the exits before O’Donnell’s Duesenberg, manufactured in Minneapolis, came anywhere near the finish lap in third place.

Chandler and the great Barney Oldfield were still on the track — with no one in the stands and the sun about to set — plodding along more than an hour from finishing when they were mercifully flagged off the track in the dusk. The most notable thing about the Oldfield performance was that his relief driver — the drivers took breaks during the race — was the later World War I flying ace, Eddie Rickenbacker.

It’s no wonder that the Tribune concluded the next day, in a heroic effort at understatement:

“The crowd could not be called enthusiastic, the length of the grind and the heat probably preventing continuous hilarity.”

Prospective ticket buyers probably didn’t imagine the downside of what was then endurance racing. The greater problem was the cost of the tickets. Ticket prices were widely acknowledged as being much too high — the lowest ticket price was $2 and that didn’t include a seat, which cost another $2.50, the equivalent of what the park board paid workers for an 8-hour workday then.

(For more detail on the 1915 race, go here. Noel Allard reconstructs the race, and the era in racing.)

Lower Prices, More Hilarity

The speedway’s promoters realized that they had to reduce prices as well as the tedium of a 500-mile race the next year. For the 1916 Fourth of July race, admission to the bleachers was cut to $1.00 and prices for seats in the grandstand began at $2.00. In hopes of more hilarity, even if not continuous, the race was shortened to 150 miles. A full day of racing was also to feature races of 50, 20 and 10 miles.

The roster of drivers was much the same as 1915: Resta chose to race in Omaha and Burman had crashed and died two months earlier in a California race. Oldfield returned, but only in capacity of referee, while his former relief driver, “Rick” Rickenbacker, had his own car to drive. (I’m no expert on race cars of the era, but it’s possible that Rickenbacker’s white Maxwell is on the far left in the photo above.) St. Paul’s own Tommy Milton, known then for his success at state fair races, but who would win two Indy 500s in the 1920s, entered in a Duesenberg. The Tribune predicted the largest race crowd in Minnesota history.

It was not to be. While I haven’t found an attendance figure for the race, there couldn’t have been many fans buying tickets because the total gate was only $8,000. We know that because at the time the flag was supposed to drop on the first race, the promoters had not yet posted the $20,000 in prize money for the races and the drivers, obviously noting the sparse crowd, refused to race until the prize money was in trustworthy hands. After a two-hour delay that caused the 50-, 20-, and 10-mile races to be scrubbed, the promoter turned over the entire gate receipts of about $8,000 and wrote a $12,000 personal check to cover the rest of the prize money for the 150-mile race. And off they went down the stilll-rough concrete track, bouncing like the promoter’s check.

Ralph De Palma won the race by a 12-minute margin in a time of just under an hour and a half, or an average speed of a bit over 91 mph. He was one of only seven finishers, with Tom Milton finishing fourth.

By 1930 the Minneapolis park board had begun the transformation of the old speedway into an airport, but a segment of the old 2-mile oval still remained. The Mendota Bridge is upper right. Note the NWA hangar among the airport buildings. The landing strip was not on the old concrete race track, which was too rough. Airplanes landed on the grass in the infield of the old race track. (J. E. Quigley, Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

That was essentially the end of the Twin City Motor Speedway. Within two days the speedway had declared bankruptcy and never recovered. The speedway that cost more than $800,000 to build went into foreclosure in August of 1916. The owner of the Indianapolis Speedway, who was also a stockholder in the Twin City Motor Speedway, declined to purchase the track. By the spring of 1917 the track property was already being mentioned as a possible site for an airfield or training ground for the navy aviation corps. Both Dunwoody Institute and the University of Minnesota had proposed to begin training military aviators and a site was needed.

A group of race car drivers led by Louis Chevrolet — yes, that Chevrolet — organized a final race at the track in 1917, which the Tribune called a “revival” race. The patient was too far gone to be resuscitated, despite a victory by Ira Vail in the 100-mile race at the much-improved average speed of more than 96 mph. Less than three months later the Tribune reported that the receiver for the bankrupt speedway had rented a portion of the grounds to a hog farmer who was fattening 500 pigs by feeding them Fort Snelling garbage. The speedway was finished, but the land was about to be given over to the service of a whole different kind of speed — and eventually the Minneapolis park board.

David C. Smith

© 2013 David C . Smith

Bombers Over Lake Nokomis

My favorite photo of Lake Nokomis was taken in 1932. The true subject of the photo was a squadron of Martin bombers visiting Wold-Chamberlain Field from Langley Field, Virginia, but beneath them is a fascinating scene of park developments.

The Martin Bomber was the first American airplane built specifically to carry bombs. First built during WWI, the biplane version of the bomber was replaced by a monoplane version designed in 1932. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The photographer isn’t listed in the Minnesota Historical Society’s database, but it may have been taken by J. E. Quigley Aerial Photography. Quigley produced most of the other aerial photos of Minneapolis from that era.

The bare ground at the left wingtip of the middle plane is the Hiawatha Golf Course under construction. The course didn’t open until 1934. Dredging in Lake Hiawatha had just been completed in 1931.

It doesn’t show up well at this size, but the Nokomis Beach is packed (beneath the front airplane). You can see the diving towers in the lake.

Also note how barren the Nokomis lakeshore is. It had been created from lake dredgings only 15 years earlier.

Four years after dredging was completed at Lake Nokomis and the dredge fill had settled, the park board cleared and graded the land. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

The dredge fill settled for four years before it was cleared of brush and willows that had grown up in the intervening years and the land was graded for athletic fields. The huge piles of brush in the background were burned. Of course the land was graded by horse teams. Even with that much time for the dredge fill to settle before it was graded, the playing fields continued to settle and were re-graded in the 1930s as a WPA project.

Even after ten years of tree growth, the lake shore doesn’t look very shaded in the 1932 photo.

The Cedar Avenue Bridge at the bottom of the aerial photo was the subject of great debate at the park board, Minneapolis City Council, the Hennepin County Board and Village Council of Richfield in the 1910s. Park superintendent Theodore Wirth’s plan for the improvement of Lake Nokomis in the 1912 annual report included rerouting Cedar Avenue around the southwest corner of the lake to eliminate a “very unsightly” wooden bridge over the edge of lake at the time. Even though the park board owned all the shores of the lake and the lake bed, the south end of the lake was then in Richfield, which is why the county and Richfield were involved in decisions on the bridge. Despite the park board position that building a bridge would be more expensive and less attractive, it was built—and paid for with Minneapolis bond funds—partly due to opposition by Richfield landowners to plans to reroute Cedar. By 1926 that line of opposition would have been partially removed when Minneapolis annexed about a mile-wide strip of Richfield that placed all of Lake Nokomis inside Minneapolis city limits.

David C. Smith

Longfellow Field: The Park that Bombs Bought

If any park in Minneapolis should be a “memorial” park, perhaps it should be Longfellow Field, because it was bought and built with war profits. It would be hard to explain it any other way. The neighborhood around present-day Longfellow Field is one of the few in the city that didn’t pay assessments to acquire and develop a neighborhood park. That’s because the park board paid for it with profits from WWI.

The story begins with the first Longfellow Field at East 28th St. between Minnehaha Avenue and 26th Avenue South. (There’s a Cub Store there now.) It was once one of the most popular playing fields in the city—and it is the largest playground the park board has ever sold.

The park board purchased the field in the upper right of this photo in 1911 and named it Longfellow Field. This photo, looking northwest, was taken from the top of Longfellow School at Lake St. and Minnehaha Ave. shortly before the land was purchased for a park. Minnehaha runs through the center of the photo and ends at E. 28th St. where the vast yards of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway begin. Minneapolis Steel and Machinery is on the left or west side of Minnehaha. (Charles Hibbard, Minnesota Historical Society)

The origins of that field as a Minneapolis park go back to 1910 when the park board’s first recreation director, Clifford Booth, recommended in his annual report that the city needed a playground somewhere between Riverside Park and Powderhorn Park.

Clifford Booth, shown here in 1910, was the first recreation director for Minneapolis parks and an unsung hero in park history.

It was the only addition he recommended to the playground sites he already supervised around the city.

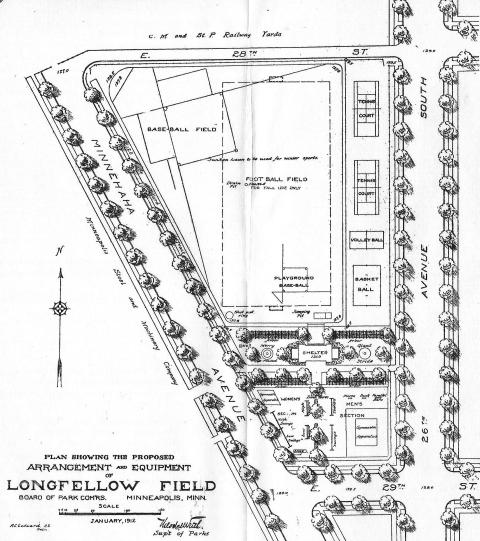

The following year, the park board found the perfect place within the area Booth suggested: an empty field just off Lake Street, about equidistant from Powderhorn and Riverside, a stones throw from Longfellow School, easily accessible by street car, and it was already used as a playing field. The park board purchased the 4-acre field in 1911 for just over $7,000 and spent another $8,000 to install football and baseball fields, tennis, volleyball and basketball courts, and playground equipment.

An architect was hired to create plans for a small shelter at the south end of the park, but when bids for the shelter came in at more than $10,000, double what park superintendent Theodore Wirth had estimated, the park board decided it couldn’t afford the shelter.

This plan for the development of Longfellow Field was published in the 1911 Annual Report of the park board. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

Despite the absence of a shelter, Wirth wrote in 1912 that Longfellow was one of the most active playfields in the city. Longfellow Field and North Commons were the venues for city football and baseball games for two years while the fields at The Parade were re-graded and seeded. The popularity of the field was attested to by the police report in the 1913 annual report of the park board, which claimed that additional police presence was necessary to control the crowds at football games at Longfellow Field and North Commons.

This Is Where the Intrigue Begins

I was surprised when I learned that the park board sold the park in 1917. The park board had never sold a park before. Why then—after 34 years of managing parks? And why this park? The park board’s explanation in the 1917 annual report was pretty weak, stating only that the field “became unavailable for a playground on account of the growth of manufacturing business in the vicinity.” The property was already on the edge of an industrial zone—see photo above—when it was purchased, so this was no revelation.

Longfellow School, on Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue, was built in 1886 and used until 1918. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The park board resolution on October 17, 1917 to sell the land provided a bit more explanation, but it still seemed less than forthcoming. It wasn’t just the growth of manufacturing business, the resolution claimed, it was also the school board’s decision to close Longfellow School and build a new school farther south. Moreover, the park board claimed that to make the playground useful it would be necessary to invest in improvements and a shelter. Given the other shortcomings of the site, the park board didn’t think it prudent to make those investments at that site.

So the park board declared that the site was no longer useful for a park, a legal requirement to get district court permission to sell the land, and it was sold for $35,000 to the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company.

At the time the park board decided to sell the field it also expressed its intention to find a “more suitable area” for a park and playground nearby in south Minneapolis. Less than two weeks after the sale was announced, the board designated land for a second Longfellow Field, the present park by that name, about a mile southeast in a much less populated neighborhood. The park board paid the $16,000 for the new land—not just four acres, but eight—and for initial improvements to the park from the proceeds of the earlier sale. It was a boon for property owners in the vicinity of the new Longfellow Field: a new park without property assessments to pay for it. The owners of three houses that had just been built across the street from the park must have been thrilled.

When I learned all of this a few years ago, I assumed that in the end the land deal was about the money—the opportunity to sell for $35,000 land the board had bought only six years earlier for $7,000. Even if you subtract the $8,000 spent on improvements, that was a nice return. And to keep that sum in context, remember that the park board shelved plans for a park shelter when bids exceeded estimates by $5,000. Thirty-five grand was a lot of money for a cash-strapped park board.

But the deal still puzzled me, especially because of the unusual way the transaction was introduced in park board records.

Park board proceedings, October 9, 1917, Petitions and Communications:

“From the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company —

Asking the Board to name a price at which it would sell the property included in the tract of park lands known as Longfellow Field.”

Talk about asking to be gouged! Who starts negotiations that way? Name a price? That seemed fishy. So did the speed of the deal. Two committees were asked to report back on the issue the following week, the first indication that someone was in a big hurry to get a deal done. The joint committees not only reported back a week later, they had come up with a price, $35,000, and had essentially concluded the deal. There hadn’t been time for much dickering over the number; the park board had a very motivated buyer. Moreover the board selected land to replace Longfellow Field only two weeks later. As decisive as early park leaders often were, this was unprecedented speed. Too much money. Too fast. Too little explanation.

Perhaps too little deduction on my part as well, but that’s where the matter stood for me the last few years until I decided recently to look into it a bit more as I was compiling a list of “lost parks” in Minneapolis. What I learned is that the decision to sell Longfellow Field had less to do with demographic shifts or manufacturing concentration in south Minneapolis than what was happening in the fields of France and the waters of the North Atlantic.

The United States Joins a World at War

For more than two years, the United States had stayed out of the Great War that embroiled much of the rest of the world. But in early 1917 Germany took the risk that a return to unrestricted submarine warfare and a blockade of Great Britain, including attacks on American ships, could bring about an end to the war before the United States could mobilize its army and economy to have a significant impact on the ground war in Europe. Germany knew that its actions would bring the U.S. into the war—and they did. The U.S. Congress declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917—and began to mobilize in earnest. Part of that mobilization was the enactment of the selective service, or draft, law in May 1917 to build an army. Another part was the procurement of weapons and equipment needed to fight a war.

Of course the manufacturing capacity for war couldn’t be built from scratch. Existing expertise, process and capacity had to be converted to war products. That meant beating plowshares into swords.

That’s where Minneapolis Steel and Machinery came in. In the fifteen years since its founding, Minneapolis Steel had become one of the leading suppliers of structural steel for bridges and buildings in the northwest. That was the “steel” part of the name. The “machinery” was represented most famously by Twin City tractors, but also by engines and parts it manufactured for other companies.

Doesn’t the logo for a line of products from the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company remind you of the logo of our favorite boys of summer? (Thanks to Tony Thompson at twincitytractors.tripod.com)

All I knew about Minneapolis Steel and Machinery was that in the 1920s it was one of the companies that merged to become Minneapolis-Moline and that it was notoriously anti-union. I didn’t know that it was an important military supplier, too.

The first evidence I found of the company’s production for war was a November 10, 1915 article in the Minneapolis Tribune that claimed the company would begin shipping machined six-inch artillery shell casings to Great Britain by January 1, 1916. The paper reported that the initial contract, expected to be only a trial order, was for almost $1.5 million.

Less than two weeks later, another Tribune report made it clear that the company’s involvement in the war was much broader. The paper reported on November 23 an order from Great Britain for 100 tractors from Bull Tractor, another Minneapolis company, for which Minneapolis Steel did the manufacturing and assembly. The tractors, still a relatively new invention, would be shipped from Great Britain to France and Russia to supplant farm horses drafted for war service or already killed in the war. Minneapolis Steel was also shipping 50 steam shovels to be used to dig trenches on the Russian front. Both orders were placed by the London distributor for both Minneapolis Steel and Machinery and Bull Tractor.

Shell orders must have continued for Minneapolis Steel and Machinery after the initial order in 1915, too, because on August 16, 1917 the Tribune reported a new order for the company. Under the headline, “Steel and Machinery Plant to Be Enlarged to Meet Uncle Sam’s Demand for Shells,” the paper reported,

“War orders just taken will necessitate a considerable enlargement of the buildings of the Minneapolis Steel & Machinery company. The company, after completing its shell contract with the British government last spring, decided not to accept any more shell orders, but the United States insisted and a large contract is the result.”

Artillery played an unprecedented role in a war in which both sides were dug into trenches. Blanket bombardments preceded most offensive actions. The result was a French countryside that resembled nothing earthly.

The report, which quoted Minneapolis Steel vice president George Gillette, continued that the company was also manufacturing steam hoists for ships and expected more contracts as the building program progressed. More contracts, unsolicited according to Gillette, did indeed materialize in the next month for carriages for 105 millimeter guns and steering engines for battleships. Those contracts reportedly required a doubling of the company’s manufacturing capacity. At that time government contracts accounted for 75 percent of the company’s output. By early 1918, the Tribune reported that Minneapolis Steel and Machinery had already been awarded $23 million in government contracts.

In the midst of this rash of new military contracts, Minneapolis Steel asked the park board to name its price for Longfellow Field. Even before the district court finished its hearings on the park board’s proposed sale, the company had obtained building permits for three new warehouses, two of them in the 2800 block of Minnehaha Ave., a short foul pop-up from home plate at the former Longfellow Field.

A Civic Duty

The spirit of the times suggests that while money may have been a factor in the park board’s prompt action, it likely was not the primary motivation for selling Longfellow Field. The park board probably viewed the sale as its civic and patriotic duty to assist the war effort—especially given the other valid reasons for moving the playground.

An example of the patriotic fervor generated by the war—to which park commissioners could not have been immune—was a dinner held at the Minneapolis Club, June 12, 1917, to raise funds for the American Red Cross, which was preparing field hospitals to treat wounded soldiers. (Did the army not have a medical or hospital corps?) The next morning the Tribune reported that in one hour the 200 business and civic leaders at the dinner pledged more than $360,000 to the Red Cross. That amount eclipsed the city’s previous one-evening fund-raising record of $336,000 for the building fund for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts a few years earlier.

The report is noteworthy especially for the accounts of the number of men present, among the wealthiest and most influential citizens of Minneapolis, who had sons and nephews on their way to France—so different from the wars of the last four decades.

“Almost every man who rose to name his contribution had a son already in France or on his way. So often did the donor, in making his contribution, add that his boy was wearing the khaki of the army or navy blue that Mr. Partridge (the emcee of the evening) called the roll to ascertain just how many present had sons or nephews in the service. Including two who announced that they themselves were entering the service, the total was 56—mostly sons.”

One of the two men present who was entering military service himself was introduced as Dr. Todd, son-in-law of J. L. Record, who was president of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery. Record pledged $10,000 to the Red Cross on behalf of his company that night.

Ernest G. Wold was one of two WWI pilots from Minneapolis who died in the air over France. The other was Cyrus Chamberlain. (Minnesota Historical Society)

Among others who pledged money were two bankers who had sons in the military aviation services, F. A. Chamberlain, chairman of First and Security National Bank, and Theodore Wold, governor of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank. Both men—and Chamberlain’s wife—were leaders in raising funds for the Red Cross and in selling Liberty Bonds. Their sons never came home. Ernest Wold and Cyrus Chamberlain died in the air over France in 1918. They were jointly honored by having Minneapolis’s airport named Wold-Chamberlain Field, a name that still stands. This was several years before the Minneapolis park board assumed control of building and operating the airport.

The Park Board During the War

Also making pledges at the Minneapolis Club dinner were park commissioners William H. Bovey and David P. Jones. Two other park commissioners who took active roles in the war effort were Leo Harris who resigned from his seat on the park board to enlist and Phelps Wyman who took a leave of absence from the park board to serve as a landscape architect for a group designing new towns for the workers needed at military factories and shipyards.

But it was the president of the park board in 1917 who had the most to lose—or prove—during those days of heated anti-German rhetoric. Francis Gross was the president of the German-American Bank in north Minneapolis. Gross had worked his way up from messenger to the presidency of the bank, which was said to be the largest “non-centrally located” bank in Minneapolis. The bank, founded in 1886, had been located on the corner of Plymouth Avenue and Washington Avenue North since 1905. Gross eventually served 33 years as a park commissioner between 1910 and 1949, earned the nickname “Mr. Park Board,” and had a Minneapolis golf course named for him. He must have been indefatigable, because his name pops up in association with many civic and financial endeavors.

Of all the park commissioners in Minneapolis history, Frank Gross is one of the most intriguing to me. If I could find some cache of lost journals of any of the city’s park commissioners since Charles Loring and William Folwell, I would most want to find those of Frank Gross. He’d be a great interview subject.

In the second year of the war, before the U. S. entry into the conflict, Gross was quoted in the Tribune expressing his view that Germany’s desire for peace was “sincere.” He urged the U. S. and other neutrals to push for peace. “I have no sympathy with the assertion that one side must be victor,” he said. “There can be a fair settlement now on nationality lines.”

Gross’s role in the war effort changed considerably after the U.S. entered the war. The tension of war in the U.S. was underscored when in March 1918, the German-American Bank officially changed its name to North American Bank. Gross asserted that the old name no longer represented the bank’s business or clients, adding “it is not good or desirable that the name of a foreign nationality be attached to an American institution.” In announcing the name change, Gross emphasized that his bank had been the first Minnesota bank to join the federal reserve system in 1915 “to do its part to establish a national banking system in our country so strong and efficient that it could meet any demand our country might make upon it.” (Tribune, March 8, 1918.) Gross’s implicit message: those demands could even include making war on the fatherland of the bank’s founders.

Only three weeks after Gross’s bank changed its name, he went on a speaking tour of towns outside Minneapolis that had large populations of German immigrants or descendants. The Tribune described his visit to Waconia on March 28, 1918. “In line with the belief of the state war savings and Liberty Loan committees that there is a distinct desire in German communities to have the war explained by persons of German birth or descent, Frank A. Gross, president of the North American bank, has spoken to several meetings composed entirely of Germans in the last few days,” the Tribune’s report began. Gross told of how he had circulated among the estimated crowd of 300 people of German descent, mostly farmers, before he spoke and found a “feeling that anyone of German birth or German descent is not wanted as a citizen of this country.”

He ascribed the feeling to the manner in which “overzealous orators” had attacked the German people, “not distinguishing between German imperialism, against which we are making war, and the German people.” Gross said that he then told the people of Waconia they “certainly were wanted as American citizens, but that the citizenship carried with it the responsibility of 100 per cent loyalty to this nation.” Gross said he also dispelled the notion that this was a “rich man’s war,” asking if they thought the “rich would send their boys to war just so their fathers could make a little more money.”

Family experience: My father, who grew up in a small town in rural Minnesota, recounts that his older brother and sister, born before WWI, spoke primarily German before they went to school, but my father and another sister, born after WWI, were never taught German.

Gross later was a prominent speaker at meetings promoting the purchase of Liberty bonds, especially in predominantly German communities such as New Ulm, Hutchinson and Glencoe, and he spoke at “Americanization” meetings—scheduled in Minneapolis neighborhoods with large “foreign elements” according to the Tribune—about “Patriotism.” He shared the podium at one such meeting in north Minneapolis with Rabbi S. M. Deinard whose subject was “The Obligation of the New Generation to the Old” and Mr. E. Avin of the Talmud Torah who gave a patriotic address in Yiddish. Gross also became an instructor, along with future Minneapolis mayor Wallace Nye, at a school for Minneapolis draftees before they were sent off to military camps.

The park board’s annual reports written while Gross was president of the board in 1917 and 1918 reveal very little of the impact of war on parks other than brief references to the heavy burden of taxes and contributions to welfare organizations and the lack of funds for park maintenance. From Gross’s other activities, however, as well as those of other park commissioners, it is apparent that the board would have had a strong sense of patriotic obligation to do what it could to assist the war effort. And that certainly extended to providing expansion space for one of Minneapolis’s largest military suppliers. So the original Longfellow Field became a casualty of war—and the neighborhood surrounding the new Longfellow Field acquired a park without having to pay property assessments.

The Last Link

One connection remains between the descendants of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery and Minneapolis parks. Minneapolis Steel and Machinery built Bull tractors, but the engines were supplied by another local company, the Toro Motor Company. Bull, Toro, get it? One contemporary newspaper account (November 17, 1918), describes Toro as a subsidiary of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery, but the website of The Toro Company today does not claim that connection. (The Toro website does claim the company produced steam steering engines for ships during WWI, however, a product that newspaper reports in 1917 attributed to Minneapolis Steel and Machinery.) Regardless of legal relationship, the two companies were closely connected and Toro is the sole survivor of the Bull, Minneapolis Steel, and Toro tractor trio.

Toro later focused its efforts on lawn-care products, famously lawn mowers, and still specializes in turf management products mostly for parks, athletic fields and golf courses. Each year in recent times, Toro and its employees, along with the Minnesota Twins Community Fund, have donated the materials, expertise and labor to rehabilitate or upgrade a baseball field in a Minneapolis park. These little gems of ball parks now exist in several Minneapolis parks, from Stewart Park to Creekview Park. Thank you, Toro. I don’t know specific park board needs now, but wouldn’t it be appropriate if Toro helped put in a fabulous field at Longfellow Park in honor of the connection long ago?

I’ll leave the final word on WWI in Minneapolis to a preacher.

“I rejoice that I am no longer needed as a partner in the grim business of killing.”

— Rev. Elmer H. Johnson, pastor of Morningside Congregational church who had worked for 11 months at the artillery shell factory of Minneapolis Steel to augment his church salary. (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, December 22, 1918)

David C. Smith

NOTE: Bob Wolff of The Toro Company provides additional details on that company in a “Comment” on the David C. Smith page. (May 31, 2012). In a separate note, Bob said he’d also look into finding photos of the first Toro turf management products used in Minneapolis parks. Stay tuned.

© David C. Smith

Leave a comment

Leave a comment