Archive for the ‘Lake of the Isles’ Tag

Harry Perry Robinson Gets a Biography

One of the larger-than-life characters from Minneapolis history in the late 1800s has his own biography now and I just ordered my copy. I wrote about Englishman Perry Robinson in my story about the Makwa Club and in an earlier story about his best friend in Minneapolis, famous interior designer and park commissioner John Scott Bradstreet. (I have just reposted my article, one of my favorites, about Bradstreet and his proposed Japanese temple on an island in Lake of the Isles.)

Escape Artist: The Nine Lives of Harry Perry Robinson by Joseph McAleer is already out as an e-book and will be released in print October 1. You can order a copy from publisher Oxford University Press or Amazon or your favorite local book store (highly recommended).

I haven’t read it yet, but I know a good bit about Robinson and I had the opportunity to hear more stories about him from author Joe McAleer. Joe visited Minneapolis while researching the Robinson story and over a burger at Red Cow we had a chance to talk about the dynamic Englishman who adopted Minneapolis for awhile–and married the daughter of one of its leading citizens. And that’s barely a footnote in a story that includes American Presidents, English Kings (modern) and Egyptian Kings (ancient) and runs from the gold mines in the United States to the trenches of World War I to Robinson being knighted Sir Harry.

Initial reviews out of the United Kingdom are very positive. If this story doesn’t end up on Netflix, I’ll be astonished. But don’t wait for the movie.

David Carpentier Smith

Ice Queens: The First Female Speed Skaters in Minnesota

Dorothy “Dot” Franey, one of the best athletes in Minnesota history, achieved her greatest athletic success as the state’s first world-class female speed skater. When a Minnesota Sports Hall of Fame was created in 1958, the inaugural class included one woman, golfer Patty Berg. The second class of inductees, in 1963, featured a second woman, Dot Franey.

In honor of Women’s History Month, let’s celebrate some of the women who first clamped on skating blades and raced on Minnesota ice. While not strictly a Minneapolis park story, Minneapolis park rinks and lakes played a central role in the development of speed skating in Minnesota. By the 1930s, when Franey was at her best, the tracks on Powderhorn Lake in Minneapolis and Lake Como in St. Paul were the premier outdoor speed skating venues in the country. Although many of Franey’s finest performances were recorded on Minneapolis ice, she was from St. Paul, and like many other skaters from downriver, she wore the colors of the Hippodrome Skating Club. The State Fair Hippodrome was converted to a skating rink in winter—covered but unheated and advertised as the largest sheet of indoor ice in the country—in December 1908.

Sadly, we will never know how great Dot Franey might have been in the speed sport she dominated. As an eighteen-year-old she represented the United States in the 1932 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid when women’s speed skating was a “demonstration” sport and won third place in the 1,000-meter race—worth a bronze medal in any sport accorded medal status. Still a teenager, she must have had high hopes for improvement in future Olympics, but that chance never came. Not only was women’s speed skating not promoted to medal status in the 1936 Winter Olympics as expected, its standing as even a demonstration sport was terminated. Women wouldn’t race on ice for Olympic medals until 1960 at Squaw Valley, California. At those Games, Dot Franey Langkop was a leader in the movement of Olympic alumni to support current United States Olympic athletes.

Franey likely would have done well had she had the opportunity to compete for Olympic medals. She won U.S. national championships, either indoor or outdoor or both, from 1933 to 1936. She never competed outside of North America, but her closest rival in the U.S., Kit Klein, won the first overall women’s world championship in 1936 in Sweden. By that measure, it’s fair to speculate that Franey would have excelled on the world stage as she had on the continental stage. She was such a dominant skater in her early 20’s that after she won a major competition in 1936 at Powderhorn Lake, a columnist for the Minneapolis Star wrote facetiously that Franey was “mad at herself” because she broke only one national record that weekend.

When Franey finally turned “pro” in 1938, meaning she could earn money from exhibitions, endorsements and appearing in figure skating shows—there was no professional speed skating circuit—her popularity was demonstrated by her endorsement of Camel cigarettes, which appeared in newspaper “funnies” around the country. Long before cigarettes were considered anathema to athletic performance, Franey claimed that the skaters she knew who smoked preferred Camels.

The timing of Franey’s decision to turn pro, may have been influenced by the decision not to include women’s speed skating in the Winter Olympics in 1936. Women’s participation in sports, which had grown steadily in the first quarter of the 20th Century, dropped off drastically in the 1930s, as notions of athleticism being unladylike were resurrected, vigorously promoted and lingered for another 40 years. In today’s world, Franey may have had even more options for athletic success as she was an all-star softball and basketball player, and a superb golfer. As it was in 1938, her only option to make a living from her athletic ability was limited to figure skating shows. Franey may have been enticed to the professional life by her friendship with Babe Didrikson, the most famous female athlete of her time, who was reported to have inked endorsement and appearance contracts worth $50,000 in her first year alone as a “pro” after she captured the nation’s attention at the 1932 Summer Olympics. That was long before Didrikson made even more money as a champion golfer when she decided to give that sport a go.

Franey endorsed Camels and began a career skating in ice shows, including producing, directing and performing in an ice show that had a 14-year run at the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas, Texas. Between Dot Franey and the Minnesota North Stars, I suspect Minnesota has given Texas about all it knows of skates on ice.

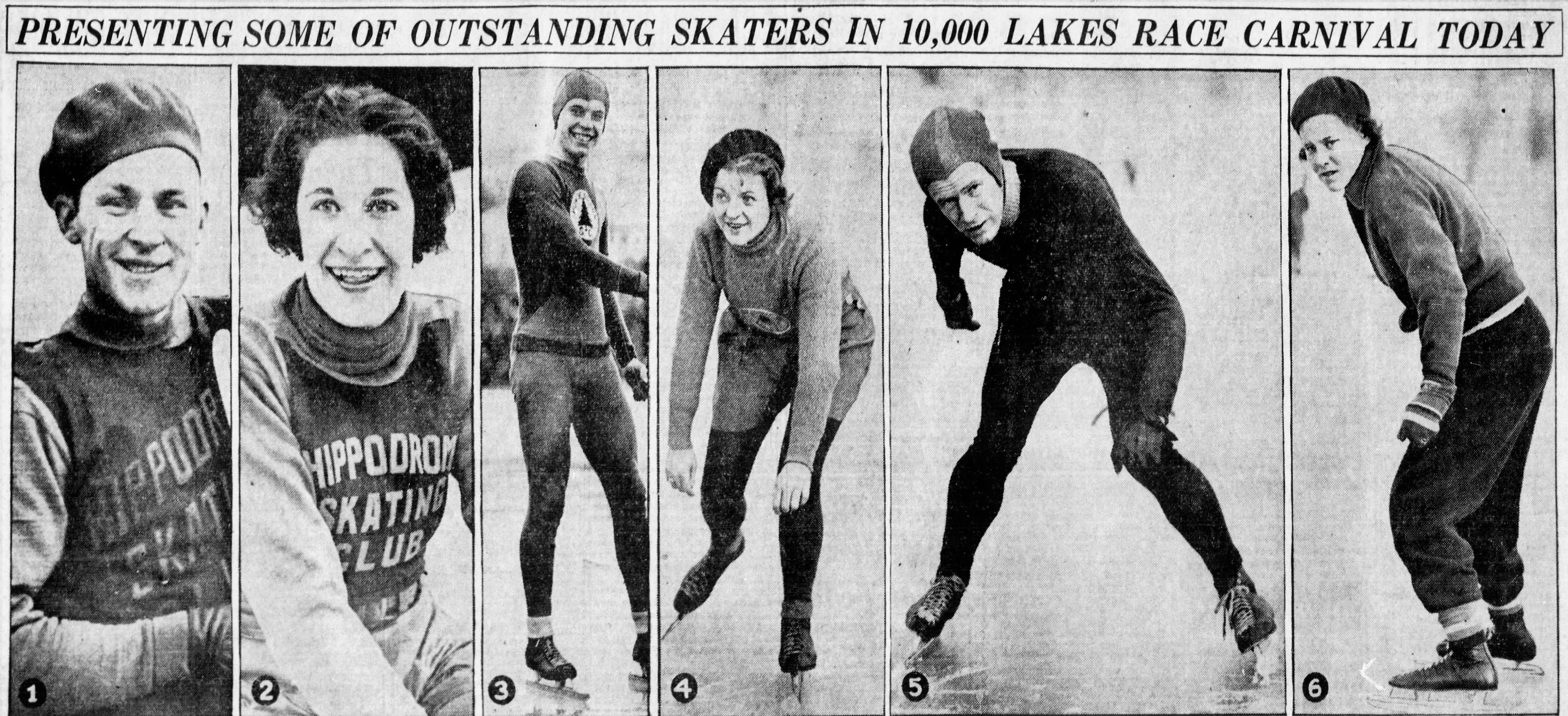

The 10,000 Lakes meet was the largest annual event at Powderhorn Lake, sponsored by the Lawrence Wennell American Legion Post. 1. Jimmy Webster, two-time national champ from St. Paul and the Hippodrome club. 2. Dot Franey. 3. Dick Beard, national junior champ from Minneapolis. 4. Olga Mikulak, Minneapolis. 5. Frank Bostrom, a Californian training in Minneapolis. 6. Patty Berg, Minneapolis “girl golf star who is also a flash on the blades.” Minneapolis Tribune, December 30, 1934.

Dot Franey was not the first female speed skater from Minnesota, just the best until then. Minnesota men were among the fastest skaters in the world in the 1890s and early 1900s. John S. Johnson, John Nilsson, Olaf Ruud from Minneapolis and A. D. Smith from St. Paul owned world or national records at distances from 100 yards to 25 miles, but there is no mention in newspapers of that time of women racing. Fancy skaters, such as Minnie Cummings, were well-known performers—she was the headline performer at the official opening of the Hippodrome Skating Rink on Christmas Day 1908—but the results of women’s races didn’t show up in newspapers until 1909.

The earliest reference to a women’s race that I’ve been able to find was a brief clip in the Minneapolis Tribune on March 3, 1909 that previewed the national professional championships in Cleveland, which featured all of the top men, including Charles Rankin from St. Paul. The story concluded, “Miss R. Leonard, champion of Ohio and Mrs. Charles Rankin will meet in a series of races for the women’s championship.”

Proof that women’s racing was in its infancy was offered by a short item in the Dayton Daily News the week of that projected race. “Girl Creates Championship” read the headline, followed by a terse report that began,

“There was no queen of the skating world and women held none of the records that set the speed limits of the ice rinks. So Miss Robina Leonard of Cleveland created a championship for women. She jumped in and set a record for the woman’s championship of the world.”

Later that year the Detroit Free Press published photos of Robina Leonard and Mabel Monroe of Detroit who were racing each other in a match arranged between Cleveland and Detroit speed skaters. Both women were photographed skating in ice-length skirts. The wind resistance created by those yards of fabric must have been demoralizing.

The race anticipated between Leonard and Rankin in Cleveland in 1909 apparently did not materialize. The reporting of the day gives no indication of how Lillian Rankin became a contender for a national championship, of other races she had won, or of women she had defeated on her rise to national title contender status. Charles Rankin was a successful short distance racer, once holding the world record for 50 yards. Lillian and Charles together oversaw the skating program at the Hippodrome in the 1910-1911 season and the Minneapolis Tribune noted at the outset that they would pay “especial attention…to women skaters.”

Rankin was reported to have skated a few races at the Hippodrome over the next couple years, among them was a warmup race before a hockey game at the Hip against the local junior mens champion, which she won by inches, and a race against a woman figure skater in which they both wore hockey skates. In other words, more novelty than legit competition.

The first time women raced as a part of local competition appears to have been at the Twin City championships sponsored by the Hippodrome Skating Club in 1914. The promoters of the Hip announced they were donating a special cup for a women’s quarter-mile race. Three women entered, but I have not yet found a record of who they were.

Interest in women’s racing appears to pick up from that beginning. In early 1915 the Minneapolis Tribune announced “First Girl Skater to Enter Ice Races at Lake Calhoun” above a posed photo of Mabel Denny in a formal gown. In a caption, the paper noted that there was a “revival” of ice skating at Lake Calhoun. For a few years interest in skating had waned in general. The Minneapolis Park Board closed its lakeside warming houses for skaters early in 1911 due to a “lack of interest.” The University of Minnesota didn’t even field a hockey team for two years in 1910 and 1911.

But that seemed to change by 1915. The Twin Cities championship at the Hip had more entries than in many years, so many that the organizers had to determine how to run heats and spread the races over two nights or risk massive collisions by running all skaters at once. (This was in the days of “pack” racing, not two at a time against the clock as is the norm now and was in Europe then.) The 1915 championship included a women’s half-mile race for the first time. The race was won by Lillian Rankin, who had dominated the past with little competition. In second place was Edna Nelson of Minneapolis, who would dominate the future with much stiffer competition.

By the start of the next skating season, public interest in skating increased dramatically. So much so that the Minneapolis Tribune ran a full-page syndicated story in mid-December on the new craze in the most fashionable circles in New York, Boston and Chicago: dancing on ice skates. Dansants a glace and Ice Teas, the paper noted, were so popular that there weren’t enough rinks or instructors to meet the demand. Adding local observation, a Tribune headline two days later proclaimed, “Revival in Skating Seen; Keen Demand for Shining Blades.” The story quoted officials of the Minneapolis hardware store association predicting that 10,000 pairs of skates would be sold in Minneapolis before the skating season was in full glide.

Edna Nelson with some of her trophies in 1917. While no longer racing in ankle length skirts, women were still carrying a lot of cloth around the rink. Minneapolis Tribune, February 18, 1917

For the next few years Edna Nelson remained at the top of women’s speed skating in Minnesota usually battling and often sharing the podium with Ethel Lee another Minneapolitan. The duels between the two became a primary draw to long-blade events on Twin Cities ovals. Their quarter-mile face-off was the featured race at the Hippodrome Skating Club’s eighth annual ice carnival in 1917. Nelson won by inches.

Neither of them, however, took part in what was billed as the first international women’s championship at Lake Placid in 1920. The only Twin City skater to score in that meet was Lillian Herman of St. Paul.

In the 1920s, Nelson and Lee gave way to Olga Munkholm of St. Paul as the fastest woman on ice in the Northwest, challenged and occasionally beaten by Gladys Malone and Violet Evans. I have been able to find very little information on any of those skaters, except that another Munkholm, Anne, perhaps a sister of Olga, was one of the leading fancy skaters of the time, performing across the western U.S. and Canada. Olga Munkholm was also the catcher on an All Star softball team from St. Paul.

Olga Munkholm was featured in a Minneapolis Tribune photo February 19, 1922 along with other stars of the Hippodrome Skating Club. In the stocking cap center right is Richard “Duke” Donovan, the first Twin Cities speed skater to compete in the Winter Olympics. He was on the 1924 team that skated at Chamonix, France.

In 1926 the Minneapolis Daily Star began promoting a Silver Skates Derby, a series of races for local boys and girls that gave them a chance to win a pair of high-quality racing skates. Silver Skates races—named for Mary Mapes Dodge’s 1865 novel, Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates—had already become popular in New York and Chicago and they helped promote skating in general, but especially for girls who were given equal billing and prizes as boys. Preliminary races for boys and girls were held at playgrounds throughout the city with the finals at Lake of the Isles where the top finishers were awarded skates and other prizes.

The Silver Skates Derby also featured open races for adults, without the prize of skates. In the first Silver Skates Derby Amy Ostgard won the senior women’s title followed by Mildred Bjork and Violet Evans in front of a crowd estimated at 20,000. Bjork became the dominant woman skater in Minneapolis for the next few years, winning the 1927 Silver Skates title and the 1928 Minnesota championship. She was one of four skaters sent by Minneapolis to the national amateur championships in Detroit in 1928, but she did not place.

When the 1929 national championships came to Lake of the Isles, Bjork must have had high expectations on her home ice and she skated well on her way to a third-place finish. She was completely overshadowed, however, by Detroit skater Loretta Neitzel who stole the show that weekend by setting three new world records in the mile, quarter-mile and sixth-mile distances.

A couple of weeks after that grand spectacle, Dorothy Franey’s name appears for the first time in results of a girls race at the indoor arena off of Lake Street in Uptown Minneapolis. It was the first indication that Franey would skate to the fore of American women speedskaters—where she would remain for much of the next decade.

Perhaps it was fitting that in Franey’s last major race before turning pro, the national indoor championships at Chicago, she was denied a final title by a new teen sensation. The winner of that national title in Chicago was Mary Dolan, a Minneapolis skater in her first season in the senior women’s division. The Queen was dead, long live the Queen. That victory was the first of many for Mary Dolan. She had skated to the top of women’s speed skating in the skate tracks of pioneer Minnesota skaters over the previous thirty years. There would be many more to come.

David C. Smith

If you know more about the skaters mentioned here or others who deserve recognition, tell us more in the comments section.

©2019 David C. Smith

Defending Minneapolis Parks

For decades, public and private parties have claimed that they need just a little bit of Minneapolis parkland to achieve their goals. And now even Governor Dayton has joined the shrill chorus of those who think taking parkland is the most expedient solution to political challenges. The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board (MPRB) is justified in examining very skeptically all desires to take parkland for other purposes and in rejecting nearly all of them categorically.

Commentators writing in December in the StarTribune asserted that the Park Board is wrong to object to just 28 feet of bridge expansion over Kenilworth Lagoon for the construction of the Southwest Light Rail Transit (SWLRT) corridor. They write as if that bridge and expansion of rail traffic across park property were the only alternative. Gov. Dayton seems to repeat the error. Other political jurisdictions involved in the proposed light rail corridor have objected to this or that provision of the project and their objections have been given a hearing, often favorable.

I didn’t hear Governor Dayton threaten to slash local government aid to St. Louis Park when officials there objected to the Met Council’s original proposals for SWLRT. But the Park Board is supposed to cave into whatever demands remain after everyone else has whined and won. Minneapolis parks are too valuable an asset – for the entire state – to have them viewed as simply the least painful political sacrifice.

Should the SWLRT bridge be built? I don’t know—but I do want the Park Board to ensure that all options have been investigated fully. That desire to consider all feasible options to taking parkland for transportation projects that use federal funds was first expressed in 1960s legislation. The legislation was meant to ensure that parkland would be taken for the nation’s burgeoning freeway system only as a last resort. In the present case, the Park Board was not convinced that the Met Council had investigated all options thoroughly once it had acquiesced to the demands of other interested parties.

A Park Board study in 1960 identified more than 300 acres of Minneapolis parkland that were desired by other entities both private and public. Hennepin County wanted to turn Victory Memorial Drive into the new County Highway 169. A few years later, the Minnesota Department of Highways planned to convert Hiawatha Avenue, Highway 55, into an elevated expressway within yards of Minnehaha Falls—in addition to taking scores of acres of parkland for I-94 and I-35W. In the freeway-building years, parkland was lost in every part of the city: at Loring Park, The Parade, Riverside Park, Murphy Square, Luxton Park, Martin Luther King Park (then Nicollet Park), Perkins Hill, North Mississippi, Theodore Wirth Park and others, not to mention the extinction of Elwell Park and Wilson Park. Chute Square was penciled in to become a parking lot.

In 1966, faced with another assault—a parking garage under Elliot Park—Park Superintendent Robert Ruhe, backed by Park Board President Richard Erdall and Attorney Edward Gearty, urged a new policy for dealing with demands for parkland for other uses. It was blunt, reading in part,

“Those who seek parklands for their own particular ends must look elsewhere to satiate their land hunger. Minneapolis parklands should not be looked upon as land banks upon which others may draw.”

With that policy in place, the Park Board resisted efforts by the Minnesota Department of Highways to take parkland for freeways or, as a last resort, pay next to nothing for it. Still, the Park Board battled the state all the way to the United States Supreme Court over plans to build an elevated freeway within view of Minnehaha Falls—a plan supported by nearly every other elected body or officeholder in the city and state, including the Minneapolis City Council.

Robert Ruhe, middle, Minneapolis Superintendent of Parks 1966-1978 proposed a tough land policy to defend against the taking of parkland for freeways and other uses. In this 1968 photo he is accepting a gift of 60 tennis nets from General Mills. Before that time, nets were not provided on most city courts. Players had to bring their own. (MPRB)

The driving force behind the park board’s defense of its land was better known as a Minnesota legislator and President of the Minnesota Senate from 1977-1981. Ed Gearty, far right, was President of the Minneapolis Park Board in 1962 when he was elected to the Minnesota House of Representatives. He had to resign his park board seat, but was then hired by the park board as its attorney. He helped devise a pugnacious strategy that helped keep park losses to freeways as small as they were. This photo with other state lawmakers was taken in 1978. Gearty deserves credit along with Ruhe, counsel Ray Haik and park board Presidents Dick Erdall and Walter Carpenter for trying to keep Minneapolis parks intact as a park “system.”

While the Supreme Court chose not to hear the Minnehaha case, its decision in a related case involving parkland in Memphis, Tenn. established a precedent that forced Minnesota to reconsider its Highway 55 plans and provides the basis for the Park Board today to investigate alternatives to taking park property for projects that use federal funds.

The Park Board is right to do so, even at the high cost it must pay—which the Met Council should be paying—and regardless of the results of that investigation. The Park Board needs to reassert very forcefully that taking parkland is a very serious matter and not the easiest way out when other arrangements don’t fall into place.

In a report to park commissioners on a proposed new land policy on April 1, 1966 Robert Ruhe concluded with these words,

“The park lands of Minneapolis are an integral part of our heritage and natural resources and, as such, should be available to all present and future generations of Minneapolitans. This is our public trust and responsibility.”

That trust and responsibility has not changed in the intervening 50 years. And it is not exercised well if the Park Board allows land to be lopped away from parks—even 28 feet at a time—without the most intense scrutiny and, when necessary, resistance. It could help us avoid horrors like elevated freeways near our most famous landmarks.

What I find most troubling about events of the past year relating to Minneapolis parks is the blatant disregard by elected officials—from Minneapolis’s Mayors to Minnesota’s Governor—of the demands and complexity of park planning and administration, as if great parks and park systems happen by accident. They don’t. They take conscientious, informed planning, funding, programming and maintaining. We can’t just write them into and out of existence as mere bargaining chips in some grander game. Parks should not be an afterthought in the crush of city or state business.

I worry when an outgoing mayor negotiates an awful agreement for a “public” park for the benefit of the Minnesota Vikings without the input of the people who would have to build and run it. I wince when an incoming mayor trumpets a youth initiative without input from the organization that has the greatest capacity for interaction with the city’s young people. And I am really perplexed when a governor makes so little effort to engage an elected body with as important a stake in a major project as the park board’s in the SWLRT.

Other elected officials seem more than happy to rub shoulders with park commissioners and staff when the Minneapolis park system receives national awards, or a President highlights the parks on a visit, or when exciting new park projects are unveiled. But they seem to forget who those people are when they are sending out invitations to the table to decide the city’s future. That is a serious and easily avoidable mistake.

David C. Smith

© 2015 David C. Smith

1911 Minneapolis Civic Celebration: Junk Mail

I have neglected these pages in recent months, yet I have so many good park stories to tell, some of them from readers. I will get to them soon I hope. In the last eight months I have discovered more fascinating information about Minneapolis parks and the people who created them than at any time since my initial research for City of Parks. But until I can get to those stories, I wanted to show you one of the more interesting bits of history I’ve encountered recently. Garish, but oddly charming.

The images below are of a promotional envelope used by a Minneapolis merchant in advance of the July 1911 Civic Celebration that was conceived primarily to celebrate the digging of the channel that connected Lake Calhoun with Lake of the Isles — as is noted at the bottom of the envelope. I found these images on an Ebay auction site and use them with permission of the seller of the envelope who sells mostly postal history under the name of “gregfree”. This envelope is for sale at an opening bid of $150 — more than I can pay. I appreciate gregfree’s willingness to let me share the image with you. Maybe you should buy it. If you do, thank him for me.

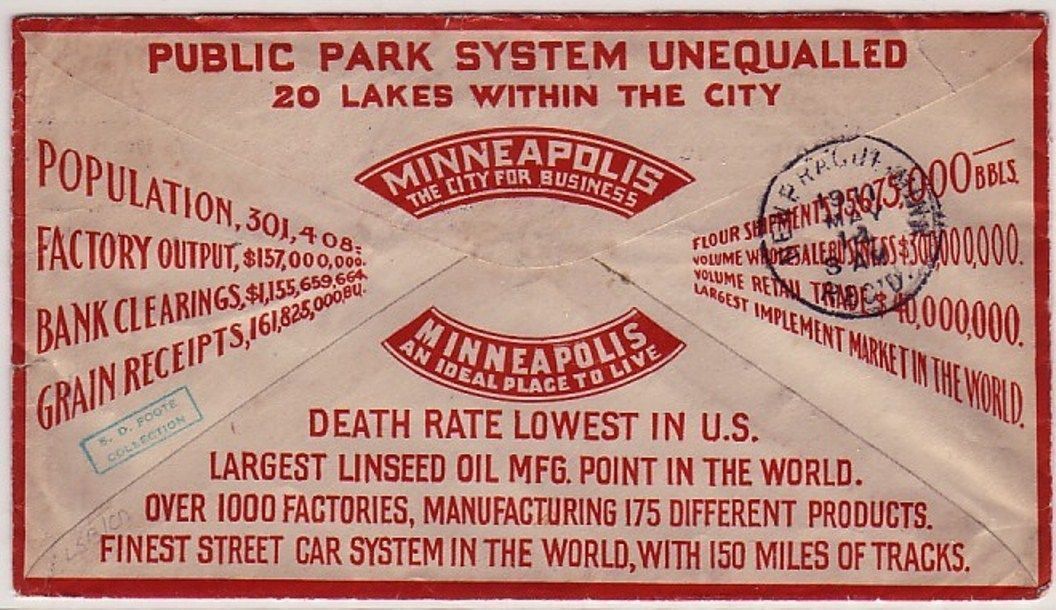

A promotional envelope used by a Minneapolis merchant. One of the objectives of the Civic Celebration was to give businesses an opportunity to contact, perhaps entertain and certainly solicit business from their clients throughout the region.

I love the background in green, a photo of the Stone Arch Bridge and Mill District, laid over a map of the city that shows the Chain of Lakes and Minnehaha Creek meeting the Mississippi River in the lower right corner.

The back of the envelope is an advertisement for Minneapolis, and from my perspective the lede is not buried — “Public Park System Unequalled.” That puts the emphasis exactly where it should be!

It’s nice to know that Minneapolis also had the lowest death rate in the United States. How that was measured, I’m not sure.

The coincidence of me finding this image now has a bit of Ouija-Board spookiness to it, because the lake connections have been on my mind — and in the news — a good bit lately. The channel that was celebrated 103 years ago between Isles and Calhoun has been in the news because the developer of a residential building at Knox Avenue and Lake Street has been pumping millions of gallons of water from a flooded underground parking garage into that channel, which has prevented it from freezing and caused considerable increase in phosphorous levels in the lake. More phosphorous means more algae. The Park Board and the City have sued to stop the pumping. Good! Such negligence on the part of a developer is astonishing. Hmmm, what do you think might happen if you put a parking garage below the water table between two lakes? I’m no engineer, but I think I’d be a tad suspicious of anyone who told me, “Hey, no problem.” The next time you hear people complaining about too much government regulation, ask them if it’s cases like this that they have in mind? I hope the Park Board uses every weapon at their disposal in this case to protect our lakes.

The other lake connection issue is not so clear-cut, but may be more important. That is the issue of tunneling under or bridging over the Kenilworth Lagoon that connects Lake of the Isles and Cedar Lake in order to build the Southwest LRT.

The history of other interests, public and private, wanting to take a little park land here or there for this or that good idea is long and sordid. For decades the park board has had to fight those who wanted just an acre or a little easement across park property. If the Park Board had acquiesced, all we’d have left of a magnificent park system would be a couple triangle parks. The reasons for taking park land have often been legitimate. For instance, I’m strongly in favor of better mass transit in Minneapolis and the entire Twin Cities metro area, but only if it doesn’t harm parks — or even the notion of parks. Is a tunnel or a bridge over Kenilworth channel better for the LRT? That question and a hornets nest of others, isn’t the right place to start. The only place to start in my very prejudiced opinion is with “Will it harm park property?” If the Park Board determines that the answer to that question is “Yes,” it is obliged to oppose those plans with all its might — regardless of how small the “harm.” Because in historical terms, “harm” seems more than precedent, it is invitation.

I have more to write about the issue. Did you know that the Park Board once went to the United States Supreme Court to prevent the State of Minnesota from taking Minneapolis parkland? True story. Til then quite an interesting envelope. Thanks again gregfree.

David C. Smith

© 2014 David C. Smith

1955 Was a Very Dry Year

It’s not a common sight. I’d never seen it myself until I saw this picture from Fairchild Aerial Surveys taken in 1955. St. Anthony Falls is completely dry.

The concrete apron at St. Anthony Falls is bone dry in 1955. The 3rd Avenue Bridge crosses the photo. Dry land — even a small structure — left (west) of the falls stand where the entrance to the lock is now. (Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Water levels were down everywhere at the time. Meteorological charts list 1955 as the 13th driest year on record in Minneapolis, but a look at longer-term data reveal that rainfall had been below normal for most of the previous 40 years. Downstream from St. Anthony Falls, the river was also very low, revealing the former structure of the locks at the Meeker Island Dam.

The old lock structure from the Meeker Island Dam protrudes from the low water in 1955. The old lock and dam between Franklin Avenue and Lake Street were destroyed when the new “high dam” or Ford dam was built near the mouth of Minnehaha Creek downriver. (Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

That dry spell had a significant impact on park property. Many park board facilities, from beach houses to boat houses and docks, were permanent structures that required proximity to the water’s edge. Parks were also landscaped and mowed to the water line and, since the depression, at least, many lakes had WPA-built shore walls that looked goofy a few feet up on dry land.

Park board annual reports provide time-lapse updates.

1948: Minnehaha Creek dry most of the year, lakes down 1.5 feet.

1949: Chain of Lakes 2 feet below normal, rainfall 2.5 inches below normal, water in Minnehaha for limited time during year

1950: Lake levels at record lows, lake channels dredged 4.5 feet deeper to allow continued use, water in Minnehaha Creek for only brief period in spring

1951: Record snowfall and heavy rains raised lake levels 0.44 feet above normal in April; flooding problems along Minnehaha Creek golf courses required dikes to make courses playable; attendance at Minnehaha Park high all year due to impressive water flow over falls.

1952: Wet early in year, dry late; lake levels stable except those that depend on groundwater runoff, such as Loring Pond and Powderhorn Lake, which were down considerably at end of year

1953: Lake levels fluctuated 1.5 feet from early summer to very dry fall; flow in Minnehaha Creek stopped in November; U.S. Geological Survey began testing water flow in Bassett’s Creek for possible diversion

1954: Again, water level fluctuations; near normal in early summer, low in fall; Minnehaha Creek again dry in November.

1955: Fall Chain of Lakes elevation lowest since 1932, but Lake Harriet near historical normal; Minnehaha dry most of year

1956: Lakes 4 feet below normal, weed control required, boat rentals incurred $10,000 loss

1957: City water — purchased at a discount! — pumped into lakes raised lake levels 1.5 feet; park board began construction of $210,000 pipeline from Bassett’s Creek, which, unlike Minnehaha Creek, had never been completely dry, to Brownie Lake.

1958: Second driest year on record; Minnehaha Creek dry second half of year; pumps activated on pipeline from Bassett’s Creek, raised water level in lakes 4.2 inches by pumping 84,000,000 gallons of water.

1959: Dry weather continued; Park board suggested reduction in water table may be result of development; Park board won a lawsuit against Minikahda Club for pumping water from Lake Calhoun to water golf course. When Minikahda donated lake shore to park board for West Calhoun Parkway in 1908 it retained water rights, but a judge ruled the club couldn’t exercise those rights unless lake level was at a certain height — higher than the lake was at that time — except in emergencies when it could water the greens only. Lakes were treated with sodium arsenite to prevent weed growth in shallower water; low water permitted park crews to clean exposed shorelines of debris.

1960: Lake levels up 4 feet due to pumping and rain fall; channels between lakes opened for first time in two years; hydrologist Adolph Meyer hired to devise a permanent solution to low water levels.

To celebrate the rise in water levels sufficient to make the channels between the lakes navigable after being closed for a couple of years, park superintendent Howard Moore helped launch a canoe in the channel between Lake of the Isles (in background) and Lake Calhoun in 1960. He seems not to mind that one foot is in the drink. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

That’s more than a decade’s worth of weather reports. The recommendation of hydrologist Adolph Meyer was very creative: collect and recycle water from the air-conditioners in downtown office buildings and stores, and pump it to the lakes. That seemed like a good idea until the people who ran all those air-conditioners downtown thought about it and realized they could recycle all that water themselves through their own air-conditioners and save a lot of money on water bills. End of good idea. Instead the park board extended its Chain of Lakes pumping pipeline from Bassett’s Creek all the way to the Mississippi River. But that’s a story for another time.

If you’ve followed the extensive shoreline construction at Lake of the Isles over the last many years, you know that water levels in city lakes remains an important, and costly, issue—and it probably always will be. It’s the price we pay for our city’s water-based beauty.

David C. Smith

Afterthought: The lowest I ever remember seeing the river was following the collapse of the I-35W bridge. The river was lowered above the Ford Dam to facilitate recovery of wreckage from that tragedy. Following a suggestion from Friends of the Mississippi River, my Dad and I took a few heavy-duty trash bags down to the river bank near the site of the Meeker Island Dam to pick up trash exposed by the lower water levels. Even then the water level wasn’t as low as in the Fairchild photos.

Comments on Lyndale Pond comments (and a very hard quiz on Minneapolis parks)

If you’re interested in the subject of a pond near Lyndale and Franklin, you might want to check out “comments” on the subject posted a few days ago. Some good information. Thanks to readers who responded and to Cheryl Luger for posing the questions in the first place.

I wanted to add that while investigating another subject I found an 1897 Minneapolis map produced by the city engineer that shows elevations. (A small section of that map is pictured below.) It’s also interesting to see where in the city you could get running water and why the city was installing water lines from a reservoir in Columbia Heights. Note the highest elevations in the city. To keep things in perspective the population of Minneapolis in 1900 was already more than 200,000. The 1890s was the first decade in four in which the population of Minneapolis didn’t nearly triple. Likely due to the depression set off in 1893.

Detail of 1897 Minneapolis map that shows parks, elevations, water lines and street car lines. (James K. Hosmer Special Collections Library, Hennepin County Library)

The complete map, as well as dozens more from around the state, are available at the Minnesota Digital Library, an excellent resource for researchers or the curious.

Unfortunately, this map has less topographical detail than the map suggested by Bill Payne in his comment on the previous article. It shows no remnant of the pond on earlier maps at Lyndale and 22nd, nor the depression that is noted there on the 1901 map Bill found. The 1897 city map shows elevation increments of 25 feet; the 1901 map shows increments of 20 feet, which may account for the difference.

Here’s the quiz

Many, many properties were added to the Minneapolis park system after this map was made in 1897. For instance, notice that there is no West River Parkway, nor a St. Anthony Parkway, nor a Victory Memorial Drive, and on and on. Most of the Grand Rounds hadn’t been built. (This map doesn’t even show Stinson Parkway, which did exist in 1897!) But there are three significant park properties on this map that are no longer park properties. Can you name them?

Click on “complete map” above, then zoom into various sections of the city to find the long-gone pieces of the park system. All were no longer park property by 1905. (Note: The island at the south end of Lake of the Isles is a good catch, but doesn’ t count because it’s still part of the lake and park. The same goes for the northern end of Powderhorn Lake, which once extended north of 32nd; it’s still part of the park. Same for Sandy Lake in Columbia Park; the lake is gone, but it’s still a park.)

Winner gets a free subscription to minneapolisparkhistory.com!

David C. Smith

NOTE (June 1, 2012): The contest is now over and Adrienne was the winner. She named Meeker Island in the Mississippi River as one park property on the map that is no longer. The other two were Hennepin Avenue South and Lyndale Avenue North. Both were parkways in 1897, but were given up by the park board in 1905. The city subsequently took responsibility for them as ordinary city streets.

Canoe Jam on the Chain of Lakes

The newspaper headline hinted of a sordid affair: “Long Line Waits Grimly in Courthouse Corridor.” Many were so young they should have been in school. Others had skipped work. They stood anxiously in the dim hallway, waiting. News accounts put their numbers at 500 when the clock struck 8:30 that April morning. Many had already been there for hours by then. They prayed they would be among the lucky ones to get permits to store their canoes at the most popular park board docks and on the lower levels of the lakeside canoe racks, so they wouldn’t have to hoist their dripping canoes overhead.

The year was 1912 and nearly 2,000 spaces were available on park board canoe racks and dock slips at Lake of the Isles, Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet. Nearly all of them were needed, which represented a huge increase over the 200 permits issued only two years earlier. The city was canoe crazed.

By contrast, in 2011 the park board rented 485 spaces in canoe racks at all Minneapolis lakes, in addition to 368 sail boat buoys at Calhoun, Harriet and Nokomis.

Canoeing was extremely popular on city lakes, especially after Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun were linked by a canal in 1911, followed by a link to Cedar Lake in 1913. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The demand for canoe racks was so great that park superintendent Theodore Wirth proposed a dramatic change at Lake Harriet at the end of 1912 to accommodate canoeists.

Wirth’s plan (above), presented in the 1912 annual report, would have created a five-acre peninsula in Lake Harriet near Beard Plaisance to accommodate a boat house that would hold 864 canoes. The boat house would have been filled with racks for private canoes, as well as lockers for canoeists to store paddles and gear. The boat house, in Wirth’s words, “would protect the boat owners’ property, and would relieve the shores of the unsightly, vari-colored canoes.”

The board never seriously considered building the boat house and that summer the number of watercraft on Lake Harriet reached 800 canoes and 192 rowboats. Most of the rowboats and about 100 of the canoes were owned and rented out by the park board. Even more crowded conditions prevailed at smaller Lake of the Isles where the park board did not rent watercraft, but issued permits for 475 private canoes and 121 private rowboats.

Rental canoes were piled up on the docks near the pavilion at Lake Harriet ca. 1912. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The park board’s challenge with so many watercraft wasn’t just how to store them, but how to keep order on the lake. An effort to maintain decorum on city lakes began in April 1913 when another year of permits was issued. The park board announced before permits went on sale that because of “considerable agitation about objectionable names” on boats and canoes the year before, permits would not be issued to canoes that bore offensive names.

The previous summer newspapers reported that commissioners had condemned naughty names such as, “Thehelusa,” “Damfino,” “Ilgetu,” “Skwizmtyt,” “Ildaryoo,” “O-U-Q-T,” “What the?,” “Joy Tub,” “Cupid’s Nest,” and “I’d Like to Try It.” The commissioners decided then that such salacious names would not be permitted the next year, even though Theodore Wirth urged the board to take the offending canoes off the water immediately.

When the naming rules were announced the next spring, park board secretary J. A. Ridgway was given absolute power to decide whether a name was acceptable. To begin with he allowed only monograms or proper names, but used his discretion to ban names such as “Yum-Yum” even though that was the name of a character in Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Mikado.” Even proper names could be improper.

Despite the strict naming rules, all but 75 of the park board’s 1400 canoe rack spaces were sold by late April, and practically all remaining spaces were “uppers” scattered around the three lakes.

The crackdown on canoe-naming wasn’t the end of the park board protecting the morals of the city’s youth on the water however. Take a close look at the 1914 photo below by Charles Hibbard from the Minnesota Historical Society’s collection.

The photo shows canoeists listening to a summer concert at the Lake Harriet Pavilion. Notice the width of the typical canoe and how two people could sit cozily side-by-side in the middle of the canoe. Now imagine how easy it would be to drift into the dark, get tangled up with the person next to you and make the canoe a bit tippy. Clearly a safety issue.

The Morning Tribune announced June 28, 1913 that the park board would have no more of such behavior. “The park board decided yesterday afternoon, ” the paper reported, “that misconduct in canoes has become so grave and flagrant that it threatens to throw a shadow upon the lakes as recreation resorts and to bring shame upon the city.”

The solution? A new park ordinance required people of opposite sex over the age of 10 occupying the same section of a canoe to sit facing each other. No more of this side-by-side stuff, sometimes recumbent. According to the paper, park commissioners said the situation had become one of “serious peril to the morals of young people.” Park police were given motorized canoes and flashlights to seek and apprehend offenders.

The need for flashlights became evident after seeing the park police report in the park board’s 1913 annual report. Sergeant-in-Command C. S. Barnard, referring to the ordinance that parks close at midnight, noted a policing success for the year. To get canoeists off the lake by midnight, the police installed a red light on the Lake Harriet boat house that was turned on to alert lake lovers that it was near 11:30 pm, the time canoes had to leave the lake. Barnard reported that the red light “has been a great help in getting canoeists off the lake by 11:30 p.m., but owing to the large number who stay out past that time (emphasis added), I would suggest that the hour be changed to 11 o’clock in order to enable the parks to be cleared by 12 o’clock.”

Indignant protest against the side-by-side seating ban arose immediately. Arthur T. Conley, attorney for the Lake Harriet Canoe Club, suggested that the park board show a little initiative and arrest those whose conduct was immoral rather than cast a slur on “every woman or girl who enters a canoe.” If Conley believed the ordinance was a slur on men and boys as well he didn’t say so, but he did add, “We dislike to hear that we are engaged in a sport which is compared with an immoral occupation and that we are on the lake for immoral purposes.”

In the face of protests, the new ordinance was not vigorously enforced and was repealed before the start of the 1914 canoe season. The Tribune noted in announcing the repeal that “the public did not take kindly to the ordinance last year and boat receipts at Lake Harriet fell off considerably on account of it.”

Despite the repeal of the unpopular ordinance, boating fell off even more in 1914. In the annual report at the close of the year Wirth attributed the decline partly to a terrible storm that passed over Lake Harriet on June 23 resulting in the drowning of three canoeists. Newspapers reported dramatic rescues of several others. By 1915 the number of canoe permits had dropped under 1400 even though canoe racks had been added to Cedar Lake, Glenwood (Wirth) Lake and Camden Pond.

The popularity of canoeing continued to decline. Wirth noted in 1917 that there had been a very perceptible decrease again in the number of private boats and canoes on the lakes. While he attributed that decline partly to unfavorable weather, he also noted the “large number of young men drawn from civil life and occupations to military service” as the United States entered WWI.

There were only six sail boats on city lakes in 1917, and all six were kept on Lake Calhoun. The first year that the park board derived more revenue from renting buoys for sail boats than racks for canoes was not until 1940. From then until now sailing has generated more revenue for the park board than canoeing.

The number of canoe permits leveled off for a while in the 1920s at about 1000 per year, but the canoe craze on the lakes had passed, much as the bicycle craze of the 1890s. During the bicycle craze the park board had built a corral where people could check their bikes while at Lake Harriet. That corral held 800 bicycles. At the peak of the much shorter-lived canoe craze in the 1910s, the park board provided rack space at Lake Harriet for 800 canoes. Popular number. Fortunately, the park board did not build permanent facilities—or a peninsula into Lake Harriet—to accommodate a passing fad.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

What Happened to John Bradstreet’s Japanese Temple in Lake of the Isles?

One hundred years ago the Minneapolis park board lost a Japanese temple and garden with a graceful torii gate and stone lanterns called ishidoro. It’s hard to say who lost it or why it was lost, or even precisely when; we know only that it disappeared sometime around a century ago. It would have been the centerpiece of a popular Minneapolis attraction — smack in the middle of Lake of the Isles. Read on…

City Ordinance Restricts Building Height Around Minneapolis Lakes

If you’re a long-time follower of Minneapolis politics, you might think this headline came from the 1988 fight to prevent a high-rise building from being constructed next to the Calhoun Beach Club facing Lake Calhoun. But you have to go back much farther in history to get to the first city ordinance to restrict construction on parkways encircling Minneapolis lakes.

I wrote a few weeks ago about Theodore Wirth’s description of the Calhoun Beach Club as a “disfigurement.” In that post I noted that Charles Loring was the first to warn the park board of the likelihood of commercial encroachment on the lake following the highly successful opening of the Lake Calhoun Bath House in July, 1912. Loring urged the park board to acquire the property across Lake Street from the bath house to prevent commercial development there. The fear, I’m sure, was the opening of saloons or dance halls. (Just two years earlier, in June 1910, the park board expanded Riverside Park when a dance hall was planned for land facing the park. The board preempted the dance hall plans by acquiring the land through condemnation.)

Since I wrote that post I’ve learned that by the time Loring made his suggestion in August 1912, the city had already passed an ordinance limiting construction on parkways around the lakes. And it had nothing to do with the Lake Calhoun Bath House. The purpose of the ordinance was essentially to facilitate the construction of this castle. Continue reading

Linking the Lakes: Making Minneapolis the Venice of North America

Happy Belated Centennial! Yesterday was the hundredth birthday of the channel that links Lake of the Isles with Lake Calhoun. It was the first of the navigable lake connections that later extended to Cedar Lake and Brownie Lake. Some background on those lake connections was featured in an earlier post on Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet.

The “Linking of the Lakes” was turned into a civic celebration that lasted nearly a week. The event was conceived and planned by the Minneapolis Publicity Club. The idea for a civic celebration was apparently hatched in November 1910 at the Minneapolis Harvest Dinner, a more modest one-evening event. While the central event of the civic celebration was the linking of the lakes, it appears to have been pretense for a party.

“It is argued by the business men that in no better way can the city merchant get in more personal touch with his country customers than through the Civic celebration when, under the spirit of merrymaking and jollity, they come together.”

Minneapolis Morning Tribune, July 2, 1911

The park board knew exactly what the intent was when it passed a resolution on December 5, 1910 that “irrespective of the benefits which may accrue to the city through such a celebration, the occasion is of such peculiar interest and significance to this board, that every effort should be made to do its full part…”

The construction of a channel between Lake Calhoun and Lake of the Isles was not a particularly challenging or imaginative endeavor. As noted in the earlier post, the project had been considered for many years and treated as a done deal as early as 1899 by landscape architect Warren Manning in his recommendations for the Minneapolis park system. In engineering terms it was simpler than the dredging that had been going on for years at Lake of the Isles, both in the 1880s and 1900s. The only construction needed for the project were bridges over the excavated channel, which were not more challenging to plan and build than bridges elsewhere in the city — although the park board’s 1909 annual report included the admission that bridge construction estimates were 50 to 100 percent over budget.

Park superintendent Howard Moore helps launch a canoe in 1960 to celebrate navigable water once again after a few years of a dry channel between Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Even the design competition for bridges, with a top prize of $800, had been disappointing. Park Superintendent Theodore Wirth wrote in the 1909 annual report, “With a few exceptions the designs submitted were not of the high-class character which it was thought the competition would bring forth.” The third prize was not even awarded. To make matters worse, the bridge over the channel from Lake of the Isles to Cedar Lake had to be partially torn down and rebuilt because it began to settle as soon as it was built, which delayed the connection of Isles and Cedar.

The connection of Lake of the Isles to Cedar Lake was finally completed in 1913, and Cedar Lake was linked to Brownie Lake in 1917. That final connection made possible a new feat of municipal athletic endurance: the swimming of the Chain of Lakes. The Minneapolis Morning Tribune, August 8, 1918 reported the setting of a new record when Dan Bessessen, the new captain of the University of Minnesota swim team and a life guard at Lake Calhoun, swam from the north end of Brownie Lake (off Superior Avenue then) to Thomas Avenue on the southern shore of Lake Calhoun in one hour and thirty-eight minutes. The swim was supervised by Frank Berry, the park board’s recreation director, who accompanied Bessessen in a boat that also carried four time keepers.

Despite the $125,000 price tag to link Isles and Calhoun, the park board appeared not to be profligate with funds. When Wirth submitted plans and an estimate for a park board float for the water parade during the celebration, it was defeated by a vote of 10-1 even though the City of Minneapolis was spending $500 for a float. Another request from Wirth to spend $200 to buy evergreen trees to temporarily cover the “unsightly” railroad embankment adjacent to the lagoon during the celebration was defeated by a vote of 11-0.

I think it’s debatable if the “Linking of the Lakes” was even the park board’s biggest role in municipal or state history in the spring and summer of 1911. I’d give top billing to another event that the park board didn’t initiate, but went along with: the donation to the park board by Clinton Morrison of the land for an art museum. The result of that transaction was the eventual construction of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in Dorilus Morrison Park.

I love the channels that connect the lakes, which Jesse Northrop said would make Minneapolis the “Venice of North America,” but I think the construction of what has become an excellent art museum, while it might not make Minneapolis the “Florence of North America,” is still of greater importance to our city today. Even without the channels between lakes Minneapolis was still blessed with exceptional natural attributes. The art museum filled an otherwise unmet need at the time, despite Thomas Barlow Walker’s incredible art collection.

David C. Smith

Comments (1)

Comments (1)