Archive for the ‘Virginia Triangle’ Tag

Lost Minneapolis Parks: The Complete List, Part III

This is the third and final installment in a series on “Lost Parks” in Minneapolis. (If you missed them, here are Part I and Part II.) These are park properties that once existed, but did not survive as parks. There is a quiz question at the end of this article. It’s very hard.

St. Anthony Parkway (partial). In 1931, the park board swapped the recently completed portion of St. Anthony Parkway from the southern tip of Gross Golf Course to East Hennepin Avenue for the land on which Ridgway Parkway was built from the golf course to Stinson Parkway. The park board gained 19 acres of land in the deal and the entire cost of constructing Ridgway Parkway was also paid. This story of the parkway “diversion” will be told in greater detail some day. It was controversial. (Read the broad outlines of the diversion of St. Anthony Parkway.) Some people have claimed that the diversion of St. Anthony Parkway is one reason for the “Missing Link” in the Grand Rounds. But that link had gone missing long before the “diversion” and wouldn’t have been found with or without the diversion.

Sheridan Field. University Avenue NE and Twelfth Avenue NE, 1.25 acres. The park board purchased the half-block of land across the street from Sheridan School for $7,000 in 1912. At the park board’s request, Twelfth Avenue was vacated between the school and park. The new playground was provided with a backstop for a baseball field and a warming house for ice-skating, but few other improvements were made. In the early 1920s park superintendent Theodore Wirth urged the park board to either expand the playground or abandon it. He believed the site was too small. It was “inadequate,” he wrote, to provide for the “large attendance (it) constantly attracts.” In the 1924 annual report Wirth presented a plan for the enlargement and development of the park, but that was the last mention of the possibility of expanding the playground. A new, much larger Sheridan School was built on the site in 1932, and the following year the park board granted the school board permission to use the park as a playground for the school, provided that all maintenance and improvements would be the responsibility of the school board. It wasn’t until 1953 that the park board officially abandoned the site. In a land swap with the school board, the park board gave up the under-sized Sheridan Park for the site of the former Trudeau School at Ninth Avenue SE and Fourth Street SE. The park at the Trudeau site became Elwell Field II.

Small Triangle. Royalston Avenue in Oak Lake Addition, 0.01 acre. The triangle was never officially named; it was called “small” because it was. Very small. (See Oak Lake.)

John Pillsbury Snyder and Nelle Stevenson Snyder the day they reached New York after being rescued from the Titanic. (StarTribune and Phillip Weiss Auctions)

Snyder Triangle. Fifth Avenue South and Grant Street, 0.06 acre. Purchased by resolution January 15, 1916 for $4,578. The park board had considered and rejected buying the triangle in 1886. The park was named for Simon P. Snyder, a real estate agent who once owned much of the land in the area. As Patrick Dea pointed out in a comment several months ago, Simon Snyder’s grandson, John Pillsbury Snyder, was a 24-year-old first-class passenger on the maiden voyage of the Titanic in 1912. He and his bride, Nelle Stevenson, were returning from their honeymoon — and survived. The triangle named for his grandfather did not. It was lost to freeway construction for I-35W. A triangle park exists today very near the old location, but it’s not owned by the park board. In 1967 the park board offered to help the state highway department landscape the new triangle between I-35W entrance and exit ramps and 10th Street. The old Snyder Triangle appears to be partly under the Grant Park building on Grant Street. I have not found a record of the price the little triangle fetched.

Stevens Circle. Portland Avenue and 6th Avenue South, 0.06 acre. The small park was named for Col. John Stevens in 1893, but at that time it was named Stevens Place. The name was changed to Stevens Circle on August 1, 1928. From its acquisition in 1885 to 1893 the property was called Portland Avenue Triangle. It is not known if a change in the shape of the park prompted the name change from triangle to place to circle. The park was transferred to the park board from the city council in 1885 according to park inventory lists, although there is no record of the transfer in park board proceedings. The only indication of park board ownership of the triangle was an entry in the expenditures of the park board for 1885 for “Triangle, Portland Avenue and Grant Street” in the amount of $1.50. The triangle became the home of a statue of Col. Stevens in 1911. The circle was given back to the city for traffic purposes in 1935, at which time the statue of Col. Stevens was moved to Minnehaha Park and placed near the Stevens House.

Stinson Boulevard (partial). From East Hennepin to Highway 8. 24 acres. A section of the boulevard was given to the city in 1962 because functionally it was a business thoroughfare, not a parkway. The section given to the city included all of the original land donated for a boulevard by James Stinson et al in 1885. It’s good we still have some Stinson Parkway remaining, because as I explained in the history of Stinson Parkway on the park board’s website, I think Stinson Parkway helped keep alive the plans of Horace Cleveland for a parkway that encircled the city. Without Stinson’s generosity, we might not have the Grand Rounds today.

Svea Triangle. Riverside Avenue and South 8th Street, 0.09 acre. The first mention of the triangle is in the minutes of the park board’s meeting of May 3, 1890 when the board received a request that it improve the triangle. The problem was that the park board didn’t own it. So, on June 27, 1890 the city council voted to turn over the triangle to the park board. The land had been donated to the city in 1883 by Thomas Lowry and William McNair and their wives for park purposes. The triangle was reportedly named on December 27, 1893 to honor Swedish immigrants who had settled in the neighborhood. It had previously been known simply as Riverside Avenue Triangle. The triangle was traded to the city council in 2011 in exchange for a permanent easement between Xerxes Avenue North and the shore of Ryan Lake in the northwestern corner of Minneapolis. The city council requested the exchange when making improvements to Riverside Avenue. Svea Triangle is the most recent park lost.

Vineland Triangle. Vineland Place and Bryant Avenue South, 0.05 acre. Transferred to the park board from the city council, May 10, 1912. The triangle was paved over in a reconfiguration of the street past the Guthrie and Walker entrances in 1973, but remains on the park board’s inventory.

Virginia Triangle. Hennepin, Lyndale and Groveland avenues, 0.167 acre. The triangle was apparently named for the Virginia Apartments adjacent to the triangle. The triangle was traded to the park board by A. W. French and wife on January 1, 1900 in exchange for a piece of land they had originally donated for a parkway along Hennepin Avenue. The triangle was sold in 1966 to the Minnesota Highway Department to accommodate interchanges for I-94. The price tag was $24,300, plus the cost of relocating the Thomas Lowry Monument, which had stood on the triangle since 1915. Read much more about Virginia Triangle and the monument here.

Walton Triangle. No property by this name was ever listed in the park board inventory or Schedule of Parks, but was included in the 1915-1916 proceedings in a schedule of wages for park keepers. Walton Triangle was included with Virginia Triangle, Douglas Triangle and Lowry Triangle and other properties in that neighborhood as the responsibility of one parkkeeper. This mysterious property likely got its name from Edmund Walton, a well-known realtor and developer, who lived on Mount Curve Avenue near where this property must have been located.

This photo from the Brady-Handy Collection at the Library of Congress is almost certainly Eugene Wilson when he was a Congressman from Minnesota 1869-1871. The photo by Matthew Brady is identified only as Hon. [E or M] Wilson, but resembles very closely other images of Wilson.

Other Losses to Freeways and Highways.

In addition to the parks listed above, the following Minneapolis parks were trimmed by construction of freeways:

- I-94: Luxton, Riverside, Murphy Square, Franklin Steele Square, The Parade, Perkins Hill, and North Mississippi, as well as easements for bridges over East and West River Parkway.

- I-35W: Dr. Martin Luther King, Ridgway Parkway, Francis Gross Golf Course. The highway department also acquired an easement from the park board to build a bridge over Minnehaha Creek.

- I-394: Theodore Wirth Park, Bryn Mawr, The Parade

- Hwy 55: Longfellow Gardens

I’ve only included properties that were officially acquired or improved, then later disposed of for some reason. The informal parks and playgrounds in empty lots that existed in many neighborhoods, but were never owned or improved by the park board, are not included. I’ve also left out small pieces of a few parks that were sold for various reasons over the years, other than those taken for highways.

If you can add to or correct this list, please let me know. Do you remember anything about any of these former parks? If you do, please send me a note so we can preserve something of them.

TRIVIA TEST. Here’s the Ph.D.-level park quiz question inspired by one of these entries. Two people had two completely different stretches of parkway named for them. One of those people was St. Anthony. (You could argue the parkways were named for the town, not the man, but this is my quiz.) The first parkway named for St. Anthony is now officially East River Parkway. Later the name was given to the parkway across northeast Minneapolis. Name the other person who had two different parkways named for him. Only one of them still has his name.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Phelps Wyman: Pioneer Landscape Architect and Minneapolis Park Commissioner

Several pioneer landscape architects were associated with Minneapolis parks, from H. W. S. Cleveland, in a very big way, to Warren H. Manning, more modestly, to Frederick Law Olmsted, who once wrote a letter to Minneapolis park commissioners at Cleveland’s request. But only one pioneer landscape architect was also elected to the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners: Phelps Wyman. (He never used his first name, Alanson, so I won’t either.) Wyman’s pioneer status in landscape architecture was determined by Charles A. Birnbaum and Robin Karson in Pioneers of American Landscape Design, which profiles about 150 American landscape architects.

Wyman is also one of a very few landscape architects not employed by the Minneapolis park board to have had designs for Minneapolis parks published in annual reports of the park board. The 1922 annual report presented Wyman’s plan for Douglas Triangle, now Thomas Lowry Park, which I wrote about here. This plan was executed in 1923. Curiously, I can find no record that Wyman was paid for the work.

Wyman’s plan for pools and pergola in 1922 annual report of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners

The next year he had another interesting plan published in the park board’s annual report, but it was never implemented. Wyman’s plan for Washburn Fair Oaks Park across from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA) Continue reading

Keep Your Thomas Lowrys Straight

Just to be clear: the Thomas Lowry Memorial is not in Thomas Lowry Park. Neither is it in Lowry Place. (See February 25 post: Lost Minneapolis Parks: Virginia Triangle.)

The Thomas Lowry Memorial, with his statue, was originally erected in 1915 on Virginia Triangle across Hennepin Avenue and a bit south from Thomas Lowry’s mansion on Lowry Hill. Thomas Lowry’s mansion was eventually purchased by Thomas Walker who then created the Walker Art Center on the site.

Thomas Lowry’s home in 1886 looking north over what is now The Parade and the Sculpture Garden. (Minnesota Historical Society)

When Virginia Triangle was erased in 1967 by freeway plans, Thomas Lowry’s statue was not moved to Thomas Lowry Park, because it didn’t exist yet, at least by that name. And it wasn’t moved to Lowry Place, also called Lowry Triangle, another lost park property, because it had already ceased to exist. Virginia Triangle was where northbound Lyndale and Hennepin avenues met at Groveland; Lowry Place was where they parted again at Vineland and Oak Grove.

Lowry Triangle is on the immediate left as you look north on Hennepin Avenue toward the Basilica. Oak Grove Street and Loring Park are on the right. Vineland Avenue, leading to the Walker Art Center, is on the left. Virginia Triangle and Thomas Lowry’s Memorial are directly behind you in 1956. (Norton and Peel, Minnesota Historical Society)

Lowry Triangle, officially named Lowry Place on May 15, 1893, was acquired by the park board from the city in 1892. The park board asked the city to hand over the triangle on November 2, 1891. It was slightly smaller than Virginia Triangle to the south. Lowry Place was at one time intended to be the home of the statue of Ole Bull that in 1897 ended up in Loring Park. Park board president William Folwell wrote to Thomas Lowry to ask if he objected to Ole Bull’s statue being placed across Lyndale Avenue from Lowry’s house on a park property that bore his name. Lowry replied that he appreciated the courtesy of being asked and had no objection. I don’t know why the statue was then placed in Loring Park instead. If you do, please tell. That’s not all I don’t know: I also don’t know why Lowry’s memorial was placed originally on Virginia Triangle instead of Lowry Triangle.

By the time the Lowry Memorial had to be moved in 1967 it was too late to shift it to the Lowry Triangle; that little patch of ground (0.16 acres) had already been acquired by the State of Minnesota in 1964 in anticipation of reconfiguring streets for the construction of I-94.

Moving the memorial to Thomas Lowry Park wasn’t an option then because at that time what is now Thomas Lowry Park at Douglas Avenue, Bryant and Mt. Curve was named Mt. Curve Triangles. That isn’t a typo, it was officially named Mt. Curve Triangles, plural, in November 1925 when its name was changed from Douglas Triangle. That was perhaps done to distinguish it from Mt. Curve Triangle, singular, which had been the name of a tiny street triangle at Fremont and Mt. Curve since 1896. That triangle was renamed Fremont Triangle in 1925, when the Mt. Curve name was shifted a few blocks east to Douglas Triangle. Mt. Curve Triangles was nearly 1.5 acres while Fremont Triangle was only .02 acre.

Thomas Lowry Park in 1925 when it was still Douglas Triangle, before it became Mt. Curve Triangles. You can find other images of the property at the Minnesota Historical Society’s Visual Resources Database, but only if you search for Douglas Triangle or Mt. Curve Triangle, not Thomas Lowry Park. (Hibbard Studio, Minnesota Historical Society)

To confuse matters, the popular name for the property was neither Douglas Triangle, nor Mt. Curve Triangles, nor Thomas Lowry Park, but “Seven Pools” after the number of artificial pools designed for the park by park commissioner and landscape architect Phelps Wyman in 1923.

Thomas Lowry and his name had nothing to do with Mt. Curve Triangles, other than the fact it was located on Lowry Hill near his old mansion, until residents in the neighborhood campaigned to have the park renamed for Lowry in 1984. (Lowry did ask the park board to improve and maintain the land in 1899, but his request was refused because the park board didn’t own the land then. It didn’t purchase the land until 1923.)

Given that there was no other place named Lowry to put the memorial to Thomas Lowry the park board chose Smith Triangle at Hennepin and 24th. That’s where it still is. The only connection between Smith and Lowry is that they probably knew each other.

Of course neither the Lowry Memorial nor Lowry Park are anywhere near Lowry Avenue, which is miles away in north and northeast Minneapolis. Lowry Avenue is much closer to the former site in Northeast Minneapolis of the Lowry School, which no longer exists either. Lowry School figured prominently in plans for Audubon Park in the 1910s. When Lowry School was built in 1915, Buchanan Street between the school and Audubon Park was vacated with the idea that the park would serve as the playground for the school.

Thomas Lowry School in 1916 showing Buchanan Street vacated between the school and Audubon Park at left. (Minneapolis Public Schools)

Those plans were never formalized. While the park provided space, it didn’t provide play facilities. Playground facilities weren’t developed at Audubon Park until the late 1950s. By that time Lowry School was already outdated and destined for closure. (For more photos of Lowry School click here.)

You can learn more about all of these park properties and how they were acquired, developed and named at the web site of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: Virginia Triangle

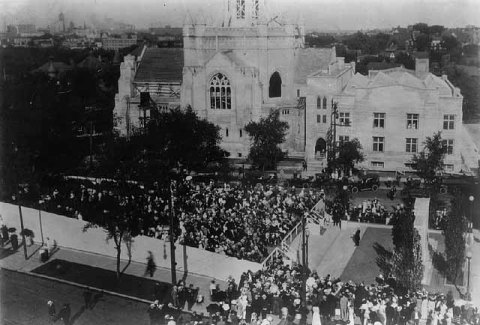

Can you tell where this photo was taken? The land in the foreground is a lost Minneapolis park: Virginia Triangle.

Virginia Triangle was at the intersection of Hennepin and Lyndale avenues; the cross street is Groveland Avenue. Hennepin crosses left to right and Lyndale right to left. The photographer was facing north. That’s the Basilica straight ahead, St. Mark’s to the right, with the trees in Loring Park between them. To your immediate right (out of the picture) is Hennepin Avenue Methodist Church. On your left, just past the cross street, is Walker Art Center. Beyond that is The Parade, athletic fields when this picture was taken, but now the home of the Sculpture Garden.

Isn’t this view lovely compared to the freeway interchanges, tunnels, etc. of today? The park board put up and decorated a huge Christmas tree in the triangle each year. I don’t know when that practice began or ended, but I’ll try to find out. If you know, send me a note.

An important memorial was installed at Virginia Triangle in 1915. The park board did not pay for the memorial but agreed that it could be placed in the park triangle. Whose memorial was it? This photo was taken at the dedication. ( That’s Hennepin Methodist church across Lyndale Avenue in the background, Hennepin Avenue in foreground.)

He had something to do with urban transit and his mansion was immediately to the left of the photographer when this picture was taken. An avenue in north Minneapolis is named for him. He donated part of the land for The Parade and paid to have it developed into a park.

Here is his statue as part of the memorial that was put on the triangle.

This is what Rev. Dr. Marion Shutter said when he spoke to the crowd gathered at the dedication above:

How grandly has the sculptor done his work! This heroic figure needs no emblazoned name to identify the original. It seems almost as if Karl Bitter (the sculptor) had stood by the door of that little Greek temple at Lakewood (cemetery), and had said: ‘Thomas Lowry, come forth.’

Virginia Triangle was acquired by the Minneapolis park board on the first day of the last century. A.W. French and his wife donated the property to the park board in a swap. The Frenches had originally donated a piece of land for Hennepin Avenue Parkway, but apparently wanted that piece back and offered what became Virginia Triangle instead. The park board accepted on January 1, 1900. The best guess is that the name of the triangle comes from “Virginia Flats,” the apartment building behind the memorial in the photo above according to a 1903 plat map.

Thomas Lowry was joined on the triangle by another statue for a time during the summer of 1931. The Knights Templar held their conclave in Minneapolis that year and requested permission to erect life-sized statues of knights on horses throughout the city. The request was approved by the park board on the condition that all park properties be returned to their original condition without cost to the park board at the conclusion of the conclave.

The statue at Virginia Triangle was probably similar to this one placed at The Gateway during the conclave. Other statues were placed at The Parade and Lyndale Park.

Virginia Triangle was eventually lost to freeway construction when I-94 was built through the city. With freeway entrances and exits needed for Hennepin and Lyndale, the triangle had to be removed even though the freeway itself was put underground below Lowry Hill and Virginia Triangle.

The state highway department paid the park board $24,300 for the triangle in 1966, plus the actual cost of relocating the Lowry Memorial. The park board chose another triangle about a half-mile south on Hennepin Avenue at 24th Street as the new site for Thomas Lowry. The low bid for moving the memorial to the new site at Smith Triangle in 1967 was $38,880.

The inscription on Lowry’s memorial reads:

Be this community strong and enduring — it will do homage to the men who guided its youth.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Leave a comment

Leave a comment