Archive for the ‘Wilson Park’ Tag

Help a Neighborhood Help a Park: Elwell Park III

The first Elwell Park in southeast Minneapolis was traded to a manufacturing company in 1952. The second Elwell Park was obliterated by a new freeway in 1962. Now the third Elwell Park needs your help. It’s not being wiped off the map like its older siblings, but it could use some TLC. The Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Association is raising money to refurbish the tiny park called a “totlot”. Anyone can contribute to this unusual little park at givemn.org, where you can also learn more about the project.

Elwell Park is often called “Turtle Park” for the mosaic reptile that is its distinguishing feature. Your contribution will help restore the mosaic tiles on the turtle shell as well as a nearby “couch.” Artist Susan Warner, who created the originals, will do the repair work. Contributions will also help refurbish the park’s metal sculptures by Marcia MacEachron and replant flowers.

Elwell Park III, located at 714 Sixth Street SE, was established in 1968 after I-35W ran over Elwell Park II and cut off the neighborhood from Van Cleve Park to the east. The park serves one of the city’s oldest residential districts, which filled in between the original town of St. Anthony at the falls and the University of Minnesota.

The dedication of the first Elwell Field in 1940. It was located at the industrial northern edge of the Marcy-Holmes neighborhood. The neighborhood draws its name from the two elementary schools that originally served the neighborhood. Two parks in the neighborhood also took their names from the schools.

You can read more about the first two Elwell Park’s in my description of Minneapolis’s “Lost Parks.”

Several Minneapolis parks lost land to the construction of freeways in the 1960s, but only two were completely wiped out: Elwell Park II and Wilson Park, which was blocking the path of I-94 ramps into and out of downtown Minneapolis north of the Basilica. (Read more about Wilson Park and other park losses to freeways here.)

The next nice weekend, ride your bike or walk to Elwell “Turtle” Park to get a feel for what you can help accomplish with a donation of a few bucks.

David C. Smith

After I posted the above I remembered a photo that people in Marcy-Holmes especially might enjoy. This is a C.P. Gibson photo on a postcard of the second Marcy School at 8th St. and 11th Ave. S.E. The school opened in 1908 and this photo was probably taken around that time. This school building no longer exists, but the property is now Marcy Park. The park board wanted to convert the first Marcy School property at 4th St. and 9th Ave. S.E. into a park around 1910, but property owners in the neighborhood didn’t want to pay assessments to create a park so the property continued as a school, renamed Trudeau School, until 1938. The park board eventually took over the original Marcy School site in 1952 and created a park there named Elwell Park. That was Elwell Park II — which now lies beneath I-35W.

This is a C.P. Gibson photo on a postcard of the second Marcy School at 8th St. and 11th Ave. S.E. The school opened in 1908 and this photo was probably taken around that time. This school building no longer exists, but the property is now Marcy Park. The park board wanted to convert the first Marcy School property at 4th St. and 9th Ave. S.E. into a park around 1910, but property owners in the neighborhood didn’t want to pay assessments to create a park so the property continued as a school, renamed Trudeau School, until 1938. The park board eventually took over the original Marcy School site in 1952 and created a park there named Elwell Park. That was Elwell Park II — which now lies beneath I-35W.

If you want more help in sorting out the many schools that have existed in the Marcy-Holmes neighborhood, many that had redundant names, visit the school inventory page at electiontrendsproject.org, still one of the most useful resources for Minneapolis historians.

What were the first two names for Loring Park?

A comment received today from Joan Pudvan on the “David C. Smith” page made me think of some little known facts in Minneapolis park history. So here’s your park trivia fix for today.

Joan asked if Loring Park was once named Central Park? Joan is a post card collector and has seen many post cards from the early 1900s labelled “Central Park.” Those cards feature images of what we know is Loring Park, so the answer to Joan is, “Yes.” When did the name change?

Central Park officially became Loring Park in 1890 when the park board’s first president, Charles Loring, was leaving the board. He, along with every other Republican on the Minneapolis ballot that year, had been defeated at the polls in a shift of political power. At the end of Loring’s tenure, his friend and fellow park advocate, William Folwell, proposed renaming Central Park for the man who had helped create it, and had even supervised much of the landscaping in the park (to H.W.S. Cleveland’s design). Loring said he would prefer that the park be named Hennepin Park for its location on that avenue, but the rest of the board agreed with Folwell that Loring should be honored. So the name was changed, a fact that the post card publishers hadn’t caught up with as many as ten or fifteen years later.

Loring was not, however, the first person to have a Minneapolis park named for him. That distinction goes to Jacob Elliot who, in 1883, donated his former garden to the city as Elliot Park. Elliot had been a prominent doctor in Minneapolis who had retired to Santa Monica, California. The handwritten document (as all were at that time) donating the land to the city as a park — recently discovered in a park board correspondence file — was signed by Wyman Elliot as the attorney-in-fact of his father Jacob Elliot. Wyman Elliot later became a park commissioner himself, when he was elected to fill out Portius Deming’s term from 1899-1901 after Deming was elected to the Minnesota legislature.

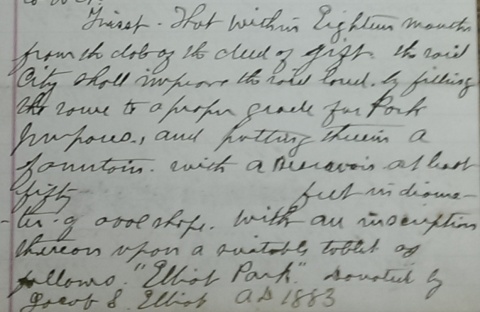

In the document that officially donated the land, the most interesting paragraph required the creation, within 18 months, of a fountain in the park with a reservoir “of oval shape” with a diameter of at least 50 feet.

One condition of Jacob Elliot’s donation of land for Elliot Park in 1883 was the creation of fountain. Elliot Park was the first Minneapolis park named for a person. The clause pictured is a part of the original document donating the land. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Additional recently found correspondence sought Dr. Elliot’s approval for the plaque he had specified.

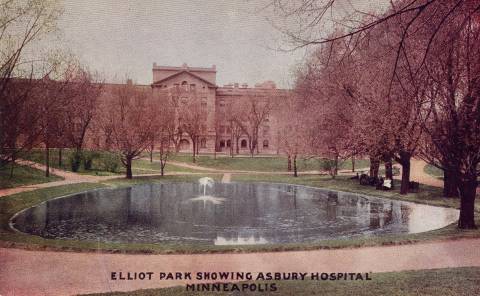

The fountain built as a condition of the donation of Elliot Park. From a postcard published around 1910. The “fountain” was a single standpipe in the middle of the pond. The Elliot Park pond was very similar to the one created in Van Cleve Park in the early 1890s.

Elliot Park fountain and Asbury Hospital from a post card with an eerie pink tinge. A soccer field now occupies this section of the park.

One other bit of naming trivia before we get to the other name for Central/Loring Park. In 1891, Judson Cross, one of the first 12 appointed park commissioners, wrote to the park board suggesting that the pond in Loring Park be named Wilson Pond for Eugene M. Wilson, one of the first and greatest park commissioners. He also served as the board’s attorney in the 1880s. He had also been elected to Congress and as Mayor of Minneapolis twice. He died at age 56 in 1890 in the Bahamas where he had gone to try to regain his health. Cross claimed that the name was appropriate because Wilson had been the strongest advocate of securing the land surrounding what had once been Johnson’s Pond for the park that became Central Park. Wilson may have played one of the most important roles in creating a park system in Minneapolis because he was one of the most prominent Democrats to strongly favor the creation of the park board. Without Wilson’s influence among Democrats, many of whom opposed the Park Act — the Republican Party supported it — Minneapolis voters may not have passed the act in the April 1883 referendum.

The board did not add Wilson’s name to Loring Park, but it did rename nearby Hawthorne Square, Wilson Park — which was particularly appropriate because Eugene Wilson’s home faced that park. Unfortunately, the park was wiped out for the construction of I-94 in 1967, so we have been without Wilson’s name in our park system for nearly 50 years.

The other name by which Central and Loring Park was known lasted only a month. In 1885, the park board voted to name the park Spring Grove Park. Without much explanation, but apparently in the face of considerable opposition, the park board backtracked to Central Park a month later.

So…Central Park, Spring Grove Park, Loring Park. I think the park board ended up in the right place.

One among many reasons for that opinion is another historical document rediscovered in the last few months: a letter from Charles Loring to the board from which the excerpt below was taken. In the letter, Loring proposes to create a Memorial Drive, a tribute to fallen American soldiers, as part of the Grand Rounds. The result was Victory Memorial Drive.

Charles Loring suggested a Memorial Boulevard and pledged to create a trust fund that would provide an annual revenue of $2,500 for the perpetual care of trees along the drive. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Without any such intention when I started writing this, I have highlighted the incredible time and resources that have been donated to the Minneapolis park system. Loring, Elliot, Wilson: all people who shared a commitment to parks and were willing to give time, money and land to the city to realize their visions of what city life should be. Their example is particularly significant now as park leaders are trying to raise funds for new park developments downtown, along the river, and in north and northeast Minneapolis. Not a bad way to be remembered.

David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: The Complete List, Part III

This is the third and final installment in a series on “Lost Parks” in Minneapolis. (If you missed them, here are Part I and Part II.) These are park properties that once existed, but did not survive as parks. There is a quiz question at the end of this article. It’s very hard.

St. Anthony Parkway (partial). In 1931, the park board swapped the recently completed portion of St. Anthony Parkway from the southern tip of Gross Golf Course to East Hennepin Avenue for the land on which Ridgway Parkway was built from the golf course to Stinson Parkway. The park board gained 19 acres of land in the deal and the entire cost of constructing Ridgway Parkway was also paid. This story of the parkway “diversion” will be told in greater detail some day. It was controversial. (Read the broad outlines of the diversion of St. Anthony Parkway.) Some people have claimed that the diversion of St. Anthony Parkway is one reason for the “Missing Link” in the Grand Rounds. But that link had gone missing long before the “diversion” and wouldn’t have been found with or without the diversion.

Sheridan Field. University Avenue NE and Twelfth Avenue NE, 1.25 acres. The park board purchased the half-block of land across the street from Sheridan School for $7,000 in 1912. At the park board’s request, Twelfth Avenue was vacated between the school and park. The new playground was provided with a backstop for a baseball field and a warming house for ice-skating, but few other improvements were made. In the early 1920s park superintendent Theodore Wirth urged the park board to either expand the playground or abandon it. He believed the site was too small. It was “inadequate,” he wrote, to provide for the “large attendance (it) constantly attracts.” In the 1924 annual report Wirth presented a plan for the enlargement and development of the park, but that was the last mention of the possibility of expanding the playground. A new, much larger Sheridan School was built on the site in 1932, and the following year the park board granted the school board permission to use the park as a playground for the school, provided that all maintenance and improvements would be the responsibility of the school board. It wasn’t until 1953 that the park board officially abandoned the site. In a land swap with the school board, the park board gave up the under-sized Sheridan Park for the site of the former Trudeau School at Ninth Avenue SE and Fourth Street SE. The park at the Trudeau site became Elwell Field II.

Small Triangle. Royalston Avenue in Oak Lake Addition, 0.01 acre. The triangle was never officially named; it was called “small” because it was. Very small. (See Oak Lake.)

John Pillsbury Snyder and Nelle Stevenson Snyder the day they reached New York after being rescued from the Titanic. (StarTribune and Phillip Weiss Auctions)

Snyder Triangle. Fifth Avenue South and Grant Street, 0.06 acre. Purchased by resolution January 15, 1916 for $4,578. The park board had considered and rejected buying the triangle in 1886. The park was named for Simon P. Snyder, a real estate agent who once owned much of the land in the area. As Patrick Dea pointed out in a comment several months ago, Simon Snyder’s grandson, John Pillsbury Snyder, was a 24-year-old first-class passenger on the maiden voyage of the Titanic in 1912. He and his bride, Nelle Stevenson, were returning from their honeymoon — and survived. The triangle named for his grandfather did not. It was lost to freeway construction for I-35W. A triangle park exists today very near the old location, but it’s not owned by the park board. In 1967 the park board offered to help the state highway department landscape the new triangle between I-35W entrance and exit ramps and 10th Street. The old Snyder Triangle appears to be partly under the Grant Park building on Grant Street. I have not found a record of the price the little triangle fetched.

Stevens Circle. Portland Avenue and 6th Avenue South, 0.06 acre. The small park was named for Col. John Stevens in 1893, but at that time it was named Stevens Place. The name was changed to Stevens Circle on August 1, 1928. From its acquisition in 1885 to 1893 the property was called Portland Avenue Triangle. It is not known if a change in the shape of the park prompted the name change from triangle to place to circle. The park was transferred to the park board from the city council in 1885 according to park inventory lists, although there is no record of the transfer in park board proceedings. The only indication of park board ownership of the triangle was an entry in the expenditures of the park board for 1885 for “Triangle, Portland Avenue and Grant Street” in the amount of $1.50. The triangle became the home of a statue of Col. Stevens in 1911. The circle was given back to the city for traffic purposes in 1935, at which time the statue of Col. Stevens was moved to Minnehaha Park and placed near the Stevens House.

Stinson Boulevard (partial). From East Hennepin to Highway 8. 24 acres. A section of the boulevard was given to the city in 1962 because functionally it was a business thoroughfare, not a parkway. The section given to the city included all of the original land donated for a boulevard by James Stinson et al in 1885. It’s good we still have some Stinson Parkway remaining, because as I explained in the history of Stinson Parkway on the park board’s website, I think Stinson Parkway helped keep alive the plans of Horace Cleveland for a parkway that encircled the city. Without Stinson’s generosity, we might not have the Grand Rounds today.

Svea Triangle. Riverside Avenue and South 8th Street, 0.09 acre. The first mention of the triangle is in the minutes of the park board’s meeting of May 3, 1890 when the board received a request that it improve the triangle. The problem was that the park board didn’t own it. So, on June 27, 1890 the city council voted to turn over the triangle to the park board. The land had been donated to the city in 1883 by Thomas Lowry and William McNair and their wives for park purposes. The triangle was reportedly named on December 27, 1893 to honor Swedish immigrants who had settled in the neighborhood. It had previously been known simply as Riverside Avenue Triangle. The triangle was traded to the city council in 2011 in exchange for a permanent easement between Xerxes Avenue North and the shore of Ryan Lake in the northwestern corner of Minneapolis. The city council requested the exchange when making improvements to Riverside Avenue. Svea Triangle is the most recent park lost.

Vineland Triangle. Vineland Place and Bryant Avenue South, 0.05 acre. Transferred to the park board from the city council, May 10, 1912. The triangle was paved over in a reconfiguration of the street past the Guthrie and Walker entrances in 1973, but remains on the park board’s inventory.

Virginia Triangle. Hennepin, Lyndale and Groveland avenues, 0.167 acre. The triangle was apparently named for the Virginia Apartments adjacent to the triangle. The triangle was traded to the park board by A. W. French and wife on January 1, 1900 in exchange for a piece of land they had originally donated for a parkway along Hennepin Avenue. The triangle was sold in 1966 to the Minnesota Highway Department to accommodate interchanges for I-94. The price tag was $24,300, plus the cost of relocating the Thomas Lowry Monument, which had stood on the triangle since 1915. Read much more about Virginia Triangle and the monument here.

Walton Triangle. No property by this name was ever listed in the park board inventory or Schedule of Parks, but was included in the 1915-1916 proceedings in a schedule of wages for park keepers. Walton Triangle was included with Virginia Triangle, Douglas Triangle and Lowry Triangle and other properties in that neighborhood as the responsibility of one parkkeeper. This mysterious property likely got its name from Edmund Walton, a well-known realtor and developer, who lived on Mount Curve Avenue near where this property must have been located.

This photo from the Brady-Handy Collection at the Library of Congress is almost certainly Eugene Wilson when he was a Congressman from Minnesota 1869-1871. The photo by Matthew Brady is identified only as Hon. [E or M] Wilson, but resembles very closely other images of Wilson.

Other Losses to Freeways and Highways.

In addition to the parks listed above, the following Minneapolis parks were trimmed by construction of freeways:

- I-94: Luxton, Riverside, Murphy Square, Franklin Steele Square, The Parade, Perkins Hill, and North Mississippi, as well as easements for bridges over East and West River Parkway.

- I-35W: Dr. Martin Luther King, Ridgway Parkway, Francis Gross Golf Course. The highway department also acquired an easement from the park board to build a bridge over Minnehaha Creek.

- I-394: Theodore Wirth Park, Bryn Mawr, The Parade

- Hwy 55: Longfellow Gardens

I’ve only included properties that were officially acquired or improved, then later disposed of for some reason. The informal parks and playgrounds in empty lots that existed in many neighborhoods, but were never owned or improved by the park board, are not included. I’ve also left out small pieces of a few parks that were sold for various reasons over the years, other than those taken for highways.

If you can add to or correct this list, please let me know. Do you remember anything about any of these former parks? If you do, please send me a note so we can preserve something of them.

TRIVIA TEST. Here’s the Ph.D.-level park quiz question inspired by one of these entries. Two people had two completely different stretches of parkway named for them. One of those people was St. Anthony. (You could argue the parkways were named for the town, not the man, but this is my quiz.) The first parkway named for St. Anthony is now officially East River Parkway. Later the name was given to the parkway across northeast Minneapolis. Name the other person who had two different parkways named for him. Only one of them still has his name.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

The “Brownie” in Brownie Lake

In the historical profile I wrote about Brownie Lake for the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board, I reported that I had found a handwritten note on an old park board document that attributed the lake’s name to the nickname of William McNair’s daughter. Now, I’ve also found a newspaper reference to that.

The Minneapolis Tribune of November 13, 1910 reported on the origin of the names of Minneapolis lakes. The article said Brownie Lake was taken from the nickname of Mrs. Louis K. Hull. Louis Hull, a prominent young attorney in Minneapolis, married Agnes McNair, one of two daughters of William McNair, on December 12, 1892.

Agnes “Brownie” McNair Hull, namesake of Brownie Lake, about 1890 (Jordan, Minnesota Historical Society)

William McNair was an influential attorney and businessman in Minneapolis who had died in 1885. Among his many real estate holdings in the city was a 1,000-acre farm that stretched across much of near north Minneapolis to include Brownie Lake. At the time of his death he was said to be in negotiation with the park board to donate a 100-foot-wide strip of land for a parkway that would have extended from Lake of the Isles, around Cedar Lake, to Farview Park in north Minneapolis. It was said he already owned nearly all the land that would be required for that four-mile parkway. His obituary (September 16, 1885, Minneapolis Tribune) claimed that he was building a mansion at 13th and Linden (facing Hawthorne Park) that would rival W. D. Washburn’s “Fair Oaks” in south Minneapolis. Louise McNair, his widow, apparently finished it, judging by this photo. Whatever happened to it? Did it outlive Fair Oaks?

McNair home, about 1890, Hawthorne Park, Minneapolis. “Brownie” McNair was married here. (Minnesota Historical Society)

A curiosity about Brownie Lake: about half of the lake was platted into streets and “blocks.” The map of Cedar Lake and environs in the 1909 annual report of the park board shows Drew, Chowen and Beard avenues platted through Brownie Lake. Much of the land for Cedar Lake Parkway, and park board control of Cedar Lake, came from donations by McNair’s widow, Louise. She was the sister of McNair’s first law partner, Eugene Wilson, who was an important park commissioner and the attorney for the first park board. Hawthorne Park, where the McNair’s were building their mansion, was later renamed Wilson Park after Eugene Wilson. Wilson Park was condemned in the 1960s to become part of the I-94 interchange.

Wilson Park, once known as Hawthorne Park, in about 1942, looking southwest with Basilica in background (Jack Delano, Minnesota Historical Society)

The park and playground west of Cedar Lake, which has always been known as Reserve Block 40, but never formally named, is in a neighborhood known as McNair Park. As residents of the Bryn Mawr neighborhood consider renaming Reserve Block 40, they could do worse than to keep the McNair Park name.

A final bit of Brownie Lake-related trivia: One of the pall bearers at William McNair’s funeral was Charles M. Loring. What makes that noteworthy in these days of political and philosophical rancor is that Loring and McNair were local leaders among Republicans and Democrats respectively. Clearly they were able to see past their political differences.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Comments (5)

Comments (5)