Archive for the ‘William Watts Folwell’ Tag

Hiawatha and Minnehaha Do Chicago

The World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago hosted the debut of Minneapolis’s most famous sculptural couple, Hiawatha and Minnehaha, in 1893.

The Minnesota building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 featured Jakob Fjelde’s sculpture of Hiawatha and Minnehaha in the vestibule.

Hiawatha and Minnehaha greeted visitors to the state’s pavilion in their modest plaster costumes nearly two decades before sculptor Jakob Fjelde’s pair took their much-photographed places on the small island above Minnehaha Falls in their bronze finery in 1912.

Hiawatha and Minnehaha in their customary place above Minnehaha Falls. This photo, from a postcard, was probably taken in the 1910s. I chose this picture not only because Hiawatha appears to be climbing a mountain of rocks to cross the stream, unlike today, but also because it is a Lee Bros. photo, the same photographers who shot the photo of Fjelde below.

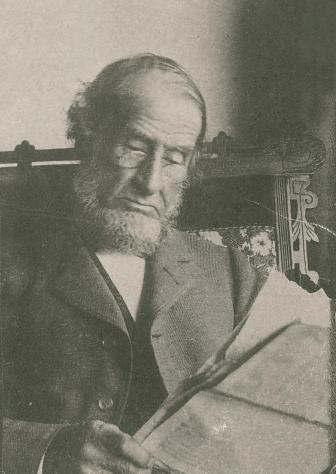

Jakob Fjelde, Lee Bros., year unknown. I like the cigar. (Photo courtesy of cabinetcardgallery.wordpress.com)

Jakob Fjelde was largely responsible for two other sculptures in Minneapolis parks. He created the statue of Ole Bull, the Norwegian violinist, in Loring Park in 1895. He also created the drawing that Johannes Gelert used after Fjelde’s death to sculpt the figure of pioneer John Stevens, which now stands in Minnehaha Park. Fjelde also created the bust of Henrik Ibsen, Norway’s most famous writer, that adorns Como Park in St. Paul. Fjelde’s best-known work other than Longfellow’s lovers, however, is the charging foot soldier of the 1st Minnesota rushing to his likely death on the battlefield of Gettysburg.

Fjelde’s simple commemoration of the sacrifice of Minnesota men at a pivotal moment in the Civil War. The sculpture was installed in 1893 and dedicated in 1897. (Photo: Wikipedia)

These thoughts and images of sculpture in Minneapolis parks were prompted in part by my recent post on Daniel Chester French, but also by another letter found in the papers of William Watts Folwell at the Minnesota Historical Society. Just two years after Fjelde’s successes with his sculptures for Gettysburg and Chicago, he wrote a poignant letter to Folwell in July 1895 seeking his support for an “extravagant” offer. Fjelde proposes to the Court House Commission, which was developing plans for a new City Hall and Court House, that he create a seven-foot tall statue of the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, John Marshall, and a bronze bust of District Court Judge William Lochren, both for the sum of $1,400. Fjelde calls the price of $1,000 for the Marshall statue “1/3 of its real value.” He explains his offer to Folwell:

“Anyone who knows a little about sculpture work will know that the sums above stated are no price for such a statue but as I for the last six months have been unable to get any work to do at all and have wife and four children to take care of and in spite of utmost economy, unable to make both ends meet, I am obliged to do something extravagant, if only I can get the work to do.”

Fjelde adds that $400 for a bronze bust of Lochren would only pay for the bronze work, meaning that he would be creating the bust free. He writes that he is willing to do so because by getting Lochren’s bust into the Court House, “it might go easier in the future to get the busts of other judges who could afford to give theirs, so I would hope that would give me some work later on.”

He concludes his plea by noting that with his proposition, “The Court House would thereby get a grand courtroom hardly equalled in the U.S.”

Although I have not searched the records diligently, I have not come across anything to suggest that the Court House Commission accepted Fjelde’s offer. That may be because barely two weeks after writing his letter, the Norwegian Singing Society, led by Fjelde’s friend, John Arctander, began to raise money for a statue of Ole Bull. Fjelde began work on that statue in 1895. When all but the finishing touches were completed on the image of the Norwegian maestro the next spring, Fjelde died. He was 37.

I can’t leave another sculpture story without returning a moment to Daniel Chester French. In a longer piece on French a couple of weeks ago, I noted that when his Longfellow Memorial at Minnehaha Falls didn’t materialize, he moved on to create an enormous sculpture for the Chicago World’s Fair. Here it is in its massive splendor. It stood 60 feet tall,

French’s Chicago sculpture was much larger than Fjelde’s, but Fjelde’s sculpture eventually found a home at Minnehaha Falls, where French’s proposed sculpture of Longfellow did not.

David C. Smith

© 2015 David C. Smith

Quotes from “Arts and Parks”: Folwell on Museums

Thanks to everyone who turned out Saturday morning at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts to listen to my thoughts on the people who created parks and a fine art society in Minneapolis in 1883. Special thanks to those who purchased a copy of City of Parks afterwards and introduced themselves. Thanks too to Janice Lurie and Susan Jacobsen for inviting me to speak and hosting the event. I want to remind everyone that all proceeds from the purchase of the book go to the Minneapolis Parks Foundation.

Quite a few of those who attended asked where they could find some of the quotes I used in my presentation, so I promised I would post them here. The most requested, especially from those who work with arts organizations, was William Watts Folwell’s remarks as reported in the Minneapolis Tribune at the laying of the cornerstone of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in 1913. I’ve provided an excerpt of his remarks from the July 31, 1913 issue of the newspaper, as well as quotes from Charles Loring and Horace Cleveland from earlier times as noted — most of which have appeared in other posts here over the years.

Folwell’s remarks included these observations on his hopes for the Institute:

“ The primary function of the institution will naturally be exhibition of works of art. I trust it will be the governing principle from the start that no inferior works shall ever have a place. Better bare walls and empty galleries than bad art. A single truly great and meritorious work is worth more in every way than a whole museum full of the common and ordinary. A few such works might make Minneapolis a Mecca for art lovers. Gift horses should be carefully looked in the mouth. I am almost ready to say that none should be received. Let benefactors give cash.

“The museum should appreciate and encourage the artistic side of all structures, public, domestic and industrial, and of all furnishings and appliances. ‘Decorative art’ should never be a term of disparagement here. Men have the right to live amid beautiful surroundings and to handle truly artistic implements.”

– William Watts Folwell, as reported in the Minneapolis Tribune, July 31, 1913.

Folwell was not one to mince words. It is noteworthy, especially considering his comments on decorative arts, that one of the influential people in the creation of the Society of Fine Arts and the Institute was interior designer and furniture maker John Scott Bradstreet. You can read much more about him here.

Other quotes from Horace William Shaler Cleveland:

“Regard it as your sacred duty to preserve this gift which the wealth of the world could not purchase, and transmit it as a heritage of beauty to your successors forever.”

–H.W.S. Cleveland, 1872“If you have faith in the future greatness of your city, do not shrink from securing while you may such areas as will be adequate to the wants of such a city…Look forward for a century, to the time when the city has a population of a million, and think what will be their wants. They will have wealth enough to purchase all that money can buy, but all their wealth cannot purchase a lost opportunity, or restore natural features of grandeur and beauty, which would then possess priceless value, and which you can preserve for them if you will but say the word and save them from the destruction which certainly awaits them if you fail to utter it.”

— H.W.S. Cleveland, Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis, presented June 2, 1883 to the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners.“The Mississippi River is not only the grand natural feature which gives character to your city and constitutes the main spring of prosperity, but it is the object of vital interest and center of attraction to intelligent visitors from every quarter of the globe, who associate such ideas of grandeur with its name as no human creation can excite. It is due therefore, to the sentiments of the civilized world, and equally in recognition of your own sense of the blessings it confers upon you, that it should be placed in a setting worthy of so priceless a jewel.”

– H.W.S. Cleveland, Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis“No city was ever better adapted by nature to be made a gem of beauty.”

— H.W.S. Cleveland to William Folwell, October 22, 1890, Folwell Papers, Minnesota Historical Society“I have been trying hard all winter to save the river banks and have had some of the best men for backers, but Satan has beaten us.”

– H.W.S. Cleveland to Frederick Law Olmsted on his efforts to have the banks of the Mississippi River preserved as parkland, June 13, 1889, Library of Congress.

The west bank of the Mississippi River Gorge from Riverside Park near Franklin Avenue to Minnehaha Park was not acquired as parkland until after Cleveland died.

“There does not seem to be another such place as Minneapolis for its constant demands upon the time of its citizens. Everyday there is something that must be done. I suppose, perhaps, this may be why we are a great city.”

– Charles Loring in a letter to William Windom, September 27, 1890, Minnesota Historical Society

It is worth noting that Loring was the president of the Minnesota Horticultural Society, vice president of the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, president of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners, president of the Minneapolis Improvement Association, and an officer in the Athenaeum and the Board of Trade. It could be said that he alone was one of the reasons Minneapolis was a great city.

Finally, the newspapers were active supporters of arts and parks through most of the history of Minneapolis. I pulled this quote from an editorial in the Minneapolis Tribune:

“While looking after the useful and necessary, let us not forget the beautiful.”

– Minneapolis Tribune, June 30, 1872

Words we could all live by.

David C. Smith

The Five Bears

This bear cage was built in Minnehaha Park in 1899 to house four black bears and one “cinnamon” bear. The 1899 report of the Minneapolis park board describes this bear “pit” built for the bears acquired by the park board over the previous few years. The cost of the construction was about $1200. It was built years before the private Longfellow Zoo was operated by Robert “Fish” Jones upstream from Minnehaha Falls. Many people believe, mistakenly, that the zoo in Minnehaha Park was Jones’s zoo. The park board began exhibiting animals in Minnehaha Park in 1894. Jones didn’t open his Longfellow Zoo until 1907, after the park board decided to get rid of most of the animals in its zoo. Jones spotted a lucrative opportunity to expand and profit from his own menagerie in the vacuum created by the park board’s decision.

“Psyche.” That was the brief caption under this photo in the 1899 annual report of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners. I assume it was the bear’s name. Later, the cages held bears named “Mutt,” “Dewey,” and “Chet,” a cub that was a crowd favorite in 1915. Dewey was badly hurt in a fall while trying to catch peanuts thrown from the crowd that year and had to be put down. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

The park board’s 1894 annual report contains the first inkling of what would become a sizable zoo. Superintendent William Berry reported,

“A deer paddock was enclosed, 50 feet square, and shelters built for deer. Two deer were added making a herd of three. Five eagles were presented to the park for which were made a cage covered with heavy wire netting.”

The financial portion of the report noted among maintenance expenditures at Minnehaha Park: Meat for eagles, $15. The next year the park board purchased three elk and accepted gifts of three more deer and three red foxes. For the deer and elk, “a portion of the glen was enclosed with a strong woven wire fence eight feet high, the length of the circuit being 2,950 feet.”

The gifts of animals kept coming and several animals were purchased, too, requiring new accommodations in Minnehaha Park. The 1897 annual report included this information from Berry, “A tank was made and enclosed for the retention of an alligator presented to the Board by the Grand Lodge B. P. O. E.” The alligator had been brought to a national convention of Elks in Minneapolis by the New Orleans delegation and left behind as a gift.

The unusual gift, matched by another free alligator the next year, lead to one of the oddest entries in the financial records of the board over the next few years. Each year the Mendenhall Greenhouse submitted its bill, increasing from $10.50 in 1898 to $14 in 1903, for “Keeping alligators in winter.” A tank in a greenhouse was the only place a warm weather creature could be housed for a Minneapolis winter. Native animals were left outside at Minnehaha, while non-native animals and exotic birds spent the winter in the park board barns at Lyndale Farmstead. Berry noted in 1899 that, “the collection of animals at the barns have proved quite an attraction and a large number of people visit them.”

By then the “collection” had become sizable and the costs had become significant, too. In the 1898 annual report William Folwell wrote,

“A list of animals now owned and kept in the parks is appended. They have been acquired by gift or at slight cost and form an attraction of no small account in the Minnehaha park. The expense of feeding and care has become considerable. A zoological garden is a great ornament to a city and is a most admirable adjunct to school education. The child who can see and study a moose, an eagle, an alligator, or any other strange beast of the field gets what no book can ever teach. It may be proper to continue the present policy, silently developed, of occasional additions to the collections as can be made at slight expense, but the matter ought not to go much further without a definite plan and counting of the cost.”

The list of animals Folwell mentioned shows that it was more than the “petting zoo” that some people think it was:

1 Moose

9 Elk

27 Deer

1 Antelope

4 Black Bears

1 Cinnamon Bear

38 Rabbits

1 Alligator

1 Ape

1 Dwarf Monkey

1 Gray Squirrel

1 Black Squirrel

10 Swans

16 Wild Geese

45 Ducks

1 Mountain Lion

2 Sea Lions

2 Timber Wolves

3 Red Foxes

1 Silver Gray Fox

4 Raccoons

2 Badgers

1 Wild Cat

5 Guinea Pigs

1 Eagle

4 Owls

5 Peacocks

6 Guinea Hens

1 Blue Macaw

1 Red Macaw

2 Cockatoos

It should be noted that not all of the birds lived at Minnehaha park. The swans and some other birds spent their summers at Loring Park. The sea lions and alligator were given new outdoor digs, which included a concrete swimming pool four feet deep, at Minnehaha in the summer of 1899. By then the park board was spending more than $2,000 a year on the care and feeding of its menagerie.

This was all a little too much for landscape architect Warren Manning who was asked to review the entire park system and make his recommendations in 1899. His sensible advice was to get rid of the exotic animals and keep only animals that could live outdoors in “accommodations that will be as nearly like those they find in their native habitat as it is practicable to secure.” Manning was ahead of his time in more than landscape architecture.

It was difficult, however, for the park board to divest a popular attraction. The park board did begin selling excess animals — including several deer to New York’s zoo — but Folwell wrote in the 1901 annual report,

“It is possible that as many people go to Minnehaha park to see the interesting animal collection as to view the historic falls.”

It took the coming of a new park superintendent in 1906 to resolve the issue. Theodore Wirth did not like the animals at Minnehaha, or in his warehouse all winter, and he felt the cramped conditions of some animals was cruel. As was his custom, he minced no words on the subject when he addressed the issue with the park board for the first time on February 5, 1906, barely a month after he took the job as park superintendent. The Minneapolis Tribune quoted Wirth in its February 6, edition:

“The present status of the menagerie is a discredit to the department and the city of Minneapolis…(it is) not only out of place and inharmonious with the surroundings, but to my mind even offensive to the highest degree. I am confident that H. W. S. Cleveland, who through his true artistic love, knowledge and appreciation of nature’s charms and teachings gave such valuable advice and suggestions for the acquirement and preservation of those grounds, would second my opinion in this matter and advise the removal of the menagerie from this spot.”

I’m sure Wirth was right about Cleveland; he would have detested the zoo. Wirth got his wish a little more than a year later when the park board reached agreement with R. F. Jones on his use of land above Minnehaha Falls for his private zoo. Ultimately the park board nearly followed the advice of Warren Manning: it kept the deer and elk in an outdoor enclosure similar to their natural habitat, but it also kept the bears in their pit and cages that didn’t resemble anything natural.

Evicting many of the animals from the zoo did not mean, however, that the park board quit acquiring animals altogether. The next year, 1908, the park board acquired a buffalo, on Wirth’s recommendation, and also acquired more bears. Of course, both animals could survive Minnesota winters outdoors. The hoofed animals remained in the park until 1923. I don’t know when the bear cages were closed or removed. The last information I have on bears in the park comes from the newspaper article in 1915 that reported Dewey’s demise. Theodore Wirth’s plan for the improvement of Minnehaha Glen, published in the park board’s 1918 annual report, still shows the bear pit beside the road to the Falls overlook.

Although the park board sent its exotic animals to R. F. Jones’s zoo in 1907, that was not the last time exotic animals were tenants on park board property. For the winter of 1911 Jones decided not to ship his “oriental and ornamental” animals and birds south for the winter. Instead he kept them in Minneapolis, where he could continue charging admission to see them, I’m sure. He found the perfect spot for such a winter display in the very heart of the city.

Jones rented the Center block at 202 Nicollet on Bridge Square from the park board. The park board had acquired the property for the new Gateway park in 1909-1910, but couldn’t develop the property until tenants leases expired in the buildings it had purchased. As those leases expired, the park board certainly had ample empty space for which a temporary tenant would have been welcome. Jones needed short-term space in a heavily travelled location, and likely got it cheap. The Minneapolis Tribune reported October 22, 1911 that “Mr. Jones thinks that trouble and money can be saved by keeping (the animals) here throughout the entire year.”

A final thought. Minneapolis Tribune columnist Ralph W. Wheelock was more than a little suspicious of R. F. Jones famous story about a sea lion escaping from his zoo down Minnehaha Creek, over the Falls and out to the Mississippi River. This is what he wrote on July 10, 1907, shortly after Jones established his zoo:

“Prof. R. F. Jones, of the New Longfellow Zoo at Minnehaha Falls, announces through the press in a loud tone of voice that he has lost a sea lion. While we would not doubt the word of so eminent a scientific authority, when we recall the clever devices of the up-to-date press agent we think we sea lion elsewhere than in the river.”

This is probably the first story written about Jones in 100 years that did not mention that he wore a top hat and went everywhere with two wolfhounds. He was a colorful character, eccentric entrepreneur and shrewd showman, but he was not the first or only one to run a zoo near Minnehaha Park. The park board beat him to it by 13 years.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

The First River Plans: Long Before “Above the Falls” and “RiverFirst”

“I have been trying hard all Winter to save the river banks and have had some of the best men for backers, but Satan has beaten us.” H. W. S. Cleveland to Frederick Law Olmsted on efforts to have the banks of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis preserved as parkland, June 13, 1889 (Letter: Olmsted Papers, Library of Congress. Photo: H. W. S. Cleveland, undated, Ramsey County Historical Society)

Considerable time, effort and expense—$1.5 million spent or contractually committed to date—have been invested in the last two years to create “RiverFirst,” a new vision and plans for park development in Minneapolis along the Mississippi River above St. Anthony Falls. That’s in addition to the old vision and plans, which were actually called “Above the Falls” and haven’t been set aside either. If you’re confused, you’re not alone.

Efforts to “improve” the banks of the Mississippi River above the falls have a long and disappointing history. Despite the impression given since the riverfront design competition was announced in 2010, the river banks above the falls—the sinew of the early Minneapolis economy—have been given considerable attention at various times over the last 150 years. There’s much more

University of Minnesota Honorary Degrees and Minneapolis Park Names

Here’s an exclusive club: William Watts Folwell, Thomas Sadler Roberts and Edward Foote Waite. Each has had a Minneapolis park property named for him, and each also received an honorary degree from the University of Minnesota.

William Watts Folwell

1925 was a big year for Folwell when, at age 92, he received the first honorary Doctor of Laws degree ever awarded by the University of Minnesota and Folwell Park was dedicated in his honor. The name for the park had been chosen in 1917, but it took eight years for the park to be finished and dedicated.

Folwell was hired as the first president of the University of Minnesota in 1869. He was elected to the Minneapolis park board in 1888 and served on the board — many years as its president — until 1906. He was the first to propose the name “Grand Rounds” for the city’s ring of parkways.

He is pictured in 1925 when he received his honorary degree, apparently in ceremonies at Memorial Stadium. Photo: Minnesota Historical Society.

Roberts was awarded an honorary Doctor of Science degree by the University of Minnesota in 1940, when he was 82. In the photo, taken sometime that year, he is perusing a book of Audubon prints.

The Thomas Sadler Roberts Bird Sanctuary in Lyndale Park near the north shore of Lake Harriet was named in his honor in 1947, a year after his death.

Roberts was a doctor known for his extraordinary capacity to diagnose unusual diseases and illnesses largely due to his prodigious memory. He retired from medicine in his 50s and devoted his time to ornithology. He taught at the University of Minnesota and was a director of the Museum of Natural History. Photo: Minnesota Historical Society.

Waite received his honorary degree from the University of Minnesota and had a Minneapolis park named for him in the same year — 1949 — when he was 89. His Doctor of Science degree honored a legal career best known for years of service as a juvenile court judge in Minneapolis. But he was far more than a wise and compassionate judge; he helped shape the field of juvenile law in the United States.

Waite is less well-known for his five-month stint as Minneapolis’s police chief in 1902. It was not an easy job in the wake of a scandal known nationally as the “Shame of Minneapolis,” centered around corrupt Mayor Albert Ames and his brother Fred, whom he had appointed police chief. David P. Jones was appointed mayor to replace the fugitive Mayor Ames and turned to his friend, Waite, an assistant district attorney with no police experience, to clean up a corrupt police force and restore public faith in law enforcement.

Waite Park was developed along with Waite Elementary School as a joint project between the park board and school board from 1949-1951. The park and school opened for the 1950 school year but final improvements to the site were not completed until the following year.

Waite is pictured snowshoeing in about 1945 at the age of 85. Photo: Minnesota Historical Society. (See another photo of Waite at the school named for him.)

From this very exclusive list it would appear that the good do not die young.

David C. Smith

Minneapolis Park History Resources: Hathitrust

If you’re researching early Minneapolis history, particularly parks, you absolutely must know about this resource: hathitrust.org.

HathiTrust is a digital library that has millions of books from university and public libraries. Most of the books are no longer copyrighted so they are in the public domain. (This includes most books published before 1923.)

What is most useful is that the volumes are searchable. Fortunately the annual reports and the proceedings of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners were widely sought after nationally and widely distributed. In old park board files, there are many cards and letters from individuals and institutions around the country requesting copies of the annual reports. Hathitrust has scanned most years of the park board’s annual reports and some proceedings up to 1923 either from the collections of the New York Public Library or the University of Michigan. The University of Minnesota also participates in Hathitrust.

“No other city gets out such artistic and complete records of its park work as does Minneapolis.”

Warren Manning’s magazine, Billerica (“The Fugitive Literature of the Landscape Art,” Vol. IV, March 1916, No. 10, Part 2), singled out the annual reports of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners for praise. The article particularly recommended the Fourteenth (1896) and Eighteenth (1900) annual reports, which were “notable for their illustrations.”

Both reports were produced while William Watts Folwell was president of the park board. As a historian Folwell understood well the value of documenting the efforts of an organization such as the park board.

HathiTrust also allows you to create an account and establish your own “collections” from its vast catalog. It’s easy to set up a guest account. Here’s what I did: I put all available issues of the park board’s annual reports and proceedings, as well as most of the early books about Minneapolis history, such as Isaac Atwater’s and Horace Hudson’s histories, into a single “collection.” I can then search the collection for any terms I want. That means I can search for Lake Harriet or Powderhorn Park and find every reference to those park properties in park board documents—and other books—over many years. Such a capability saves hours of research because the park board annual reports and proceedings in the early years did not have indexes.

Annual reports are not available for some years in the Minneapolis park board’s first decade, but all annual reports 1895-1922 are available. HathiTrust also has many issues of the Minneapolis City Council proceedings, which provides for another layer of research. HathiTrust has also scanned many park board annual reports from 1923-1960. Due to copyright restrictions the full text of those reports is not available online, but a search will reveal if and how often terms do appear in those volumes. Not as helpful as full-view text searches, but still a big time-saver. You can then go straight to the pages you want in a library.

Give hathitrust.org a try. You’ll be amazed at what you’ll be able to find. The digitization for HathiTrust was done by Google, but the collection is far more extensive than what is available at Google Books.

David C. Smith

And the answer is….French

In a post on December 29, 2010 I asked how these two pictures were related to the creation of Minneapolis parks.

Nobody has come up with the right obscure answer! So I’ll tell you.

The photos are of the most famous works of American sculptor Daniel Chester French. (The best example of French’s work in Minneapolis is the statue of John Pillsbury at the University of Minnesota.)

Here is the connection — and the key word is “related”:

Daniel Chester French’s older brother was William Merchant Richardson French. That’s this guy:

(Their father was Henry Flagg French who was the number two man in the U. S. Treasury Department. For eight months in 1881 he worked under Secretary of the Treasury William Windom, a U. S. Senator from Minnesota who resigned his Senate seat to become Treasury Secretary for President James Garfield. After those eight months, Windom resigned at Treasury and was elected to fill his own open seat in the Senate. He served as Secretary of the Treasury again from 1888 until his death in 1891.)

The important connection of William French to Minneapolis parks is that after graduating from Harvard in 1864 and a year at MIT studying engineering he moved to Chicago and met a man in the new and unusual profession of landscape gardening. It’s not clear how it came about, but in 1870 William French became the partner of a man thirty years older than he was. That pioneering landscape architect was Horace Cleveland.

Of course, young William, who was eager I’m sure to earn his keep with his much more experienced partner, went through his list of connections to identify potential clients. He likely recognized that one name on his list might provide useful contacts in a young city west of Chicago, Minneapolis. That contact was his cousin, George Leonard Chase, who was rector at the episcopal church in the small town of St. Anthony, which was springing up beside the falls of that name. Now it just happened that Chase had married one of the Heywood girls, Mary. And that was a funny thing because Chase’s best friend married Sarah Heywood, Mary’s sister. He and his best friend had lived together while they were students at Hobart College in New York. In fact, Chase had apparently had some influence with the regents of the University of Minnesota when they were hiring the university’s first president in 1869. Chase’s friend and brother-in-law by marriage was hired for that job. His name was William Watts Folwell.

William Watts Folwell: Show them in their best days

William Watts Folwell was an accomplished man: Union Army engineer, first president of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis park commissioner for 18 years, author of a four-volume history of Minnesota. The list goes on and on. Not least, he is one of my heroes.

Many photographs of Folwell exist, including some posted on this site, but today I will follow Folwell’s advice. In 1911, when Folwell was 78, he wrote to Minnesota Historical Society President Warren Upham:

“Let me make a suggestion in regard to portraits of men in all your publications. Don’t print “old man pictures,” but show the men as they were in their best days if possible. The likeness of General Sibley in General Baker’s book is atrocious. Sibley was a splendid figure in his prime, and ought so to be remembered.”

(Wiliam Watts Folwell: Autobiography and Letters of a Pioneer of Culture, Ed. Solon J. Buck. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1933)

So here is William Watts Folwell dressed for his wedding to Sarah Heywood when he was 30 in 1863. At the time he was an enlisted engineer in the Union Army. While it appears from his shoulder patch here that he was a captain at the time, he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel, the highest possible for an enlisted man, and commanded an engineering company of 450 men in several important Civil War battles. Folwell was hired as the first president of the University of Minnesota six years after he was married.

William Watts Folwell photographed in his Union Army uniform for his wedding in 1863 to Sarah Heywood. (Powelson, Minnesota Historical Society)

David C. Smith

Inspiration, Ideas and Ideals (Courtesy of William Watts Folwell)

Park history provides more than pretty pictures. Thanks to people such as William Folwell, it also gives us inspiring words. Such inspiration has perhaps never been needed more than now when political discourse is dominated by petty self-interest and shallow swagger.

“We owe it to our children and to all future dwellers in Minneapolis to plan on a great and generous scale. If we fail to accomplish, let them know it was not for lack of ideas or ideals.”

— William W. Folwell, President, Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners, Eighteenth Annual Report, 1900

William W. Folwell attended the dedication of facilities at Folwell Park, July 4, 1925. He was 92. (Minnesota Historical Society, por 12574 r18)

David C. Smith

Leave a comment

Leave a comment