Archive for the ‘Bryn Mawr’ Tag

Two New Park-Related Books by Joe Bissen and Sue Leaf

I’m happy to recommend two books that I’ve recently added to my shelves on Minneapolis history.

Fore! Gone. Minnesota’s Lost Golf Courses 1897-1999 by Joe Bissen. Joe contacted me after reading my pieces on the old Bryn Mawr Golf Club before it spun off Minikahda and then Interlachen. We ended up spending an enjoyable morning roaming around the Bryn Mawr neighborhood trying to pin down the location of the course and the clubhouse. It was a task made more difficult by the changes in street names and house numbering systems over the last 115 years. Bryn Mawr is only one of many long-gone golf courses that Bissen writes about in this entertaining book. If you’ve played much golf in the state, you’ll find these stories especially enjoyable, but you needn’t be a fan of “a good walk spoiled” to enjoy these stories of changing landscapes.

For Minneapolis history buffs, I’d recommend a visit to Joe’s blog as well, where he goes into greater detail on his search for more info on the ancient Camden Park Golf Club that was supposedly built around Shingle Creek by employees of C.A. Smith’s lumber company.

A Love Affair with Birds: The Life of Thomas Sadler Roberts, by Sue Leaf. The wild landscape north of Lake Harriet, which is named for Thomas Sadler Roberts, is widely known as a bird sanctuary in the Minneapolis park system. What is probably less-well known, is that the entire Minneapolis park system is a bird refuge — and has been for about 75 years. Roberts was a doctor and later in life an ornithologist at the University of Minnesota who was instrumental in creating the fabulous displays at the Bell Museum of Natural History at the U.

When I was still in grade school in the 1960s I remember my parents taking us to see those displays on Sunday afternoons. I don’t think they are as heavily visited now as they once were, but I had such fond memories of those life-like exhibits that I took my daughter there several times in this century. A couple of years ago I included in this blog a photo of wolves attacking a moose outside the museum.

Now, thanks to author Sue Leaf, I know the story of how the Bell Museum came into existence — as well as many other details of the life of a remarkable man. Leaf places Roberts’ life in the context of the early history of Minneapolis. His friends, colleagues and benefactors included many influential people in the creation of the city’s economy and institutions.

The story Leaf tells heightens appreciation for the wildlife habitat that Minneapolis parks have preserved not only in the Thomas Sadler Roberts Bird Sanctuary, but throughout the park system.

I hope you will keep both books in mind for your book-inclined friends and family this gift-giving season. Or buy one for yourself and save it for a day when you’re snowed in. Sorry, but you know it’s coming.

David C. Smith

Post script: Check back in a couple days and perhaps you can help us solve a mystery in Thomas Sadler Roberts Bird Sanctuary.

© 2014 David C. Smith

Bryn Mawr Golf Course Update

I recently met with Joe Bissen who is writing a book on lost Minnesota golf courses. We walked around the Bryn Mawr neighborhood trying to determine the location of the old clubhouses of the Bryn Mawr Golf Course. The course, which existed from 1898 to 1911 near the Penn Avenue-Cedar Lake Road intersection, spawned both the Minikahda and Interlachen clubs before it closed and the course disappeared.

The Bryn Mawr course had two clubhouses. The first was located at 95 Elm Street, now Morgan Avenue South, which had been a private residence of the Woodburn family before it was purchased in 1898 and converted into a clubhouse. The second clubhouse was built nearby. Bissen has found the address of the second clubhouse in 1908 to be 97 Oliver Avenue North.

Here’s the challenge. At that time Superior Avenue, what is now roughly I-394, was the dividing line between north and south street addresses, but now that dividing line is about a half-mile north at Chestnut Avenue. What was once Oliver Avenue North in Bryn Mawr is now Oliver Avenue South. Can anyone shed light on the present address of what was once 95 Oliver Avenue North? Joe and I suspect it was in the 400 or 600 block of what is now Oliver Avenue South. (Futher complicating addresses in the neighborhood there are no 500 addresses—straight from 490s to 600s!)

Can any Bryn Mawr historians solve this puzzle? Let me know and I’ll put you in touch with Joe. Would property abstracts show old addresses? And why (when) was Bryn Mawr moved from north to south?

Joe Bissen is researching lost golf courses throughout the state, so if you know of other courses, such as the Camden Golf Club in north Minneapolis, which disappeared with hardly a trace, Joe would like to know more about them.

David C. Smith

Prospect Park Garden Club wins Triangle Award; Orlin Triangle is smallest park.

An update on the smallest park triangles:

The beautiful triangles in Prospect Park are maintained by the Prospect Park Garden Club. I learned that in the delightful backyard of Mary Alice Kopf last Saturday during the Annual Garden Walk and Plant Sale sponsored by the Prospect Park Garden Club. Nobody I talked to in Prospect Park knew, however, why some triangles were taken over by the park board and others weren’t. So if you know…

I am certain now that Orlin Triangle is the smallest of the street triangles in the Minneapolis park system.

The second smallest is Elmwood Triangle at Luverne and Elmwood just north of Minnehaha Creek near Nicollet. Basic grass and tree — and two dead end signs. Seems a bit ominous.

Elmwood Triangle, the second smallest park in Minneapolis, listed at 0.01 acre. Based on my rough measurements, bigger than Orlin Triangle.

The most attractive triangle park outside of Prospect Park is Laurel Triangle in Bryn Mawr. My next task is to find out who takes care of this park. Laurel Triangle was purchased by the park board for $700, most of which went to pay back taxes, in 1911, so it’s a little older park officially than the Prospect Park triangles.

Laurel Triangle, at Laurel and Cedar Lake Road, is beautiful too, in a wilder way than the Prospect Park triangles. So big it has two sidewalks and two stop signs. There’s a little stone bench next to the tree that I’d love to sit on with a cup of coffee.

Another of the smallest triangles is Rollins Triangle at Minnehaha and E. 33rd St. across from Peace Coffee. Quite a different environment on a busy thoroughfare and considerably larger than the smallest. Farther south, Adams Triangle on Minnehaha and 42nd, is one-third-acre, one of the larger triangles.

Rollins Triangle has a newspaper stand, a bus bench, vent pipes and a bit of a garden that’s overgrown. Definitely larger.

Most triangles are named for streets, but Rollins was named for the real estate development, Rollins Addition, in the neighborhood. It was taken over by the park board at the request of the city council in 1929 and officially named in 1931.

Someday soon I’ll visit the two remaining triangles listed at 0.01 acre in the park board’s inventory, Sibley and Oak Crest in northeast Minneapolis. But judging by their images on Google maps they are both larger than triangles shown here.

I purchased several plants for my yard at the Prospect Park Garden Sale at Pratt School. This whole business of planting triangles inspired me. And that was one objective of early park planners — to encourage us to replicate the pretty little public gardens on our own property.

David C. Smith

The Award for Prettiest Triangles Goes to….Prospect Park!

The prettiest little parks in Minneapolis are in Prospect Park.

I visited that neighborhood recently — it’s not a place you pass through conveniently on your way to anywhere else — to see what kind of damage the Emerald Ash Borer had done to Tower Hill Park.

The view from Tower Hill. One of three “overlook” views of the city from parks that you should check out. The others are Deming Heights Park and Theodore Wirth Park. (All photos: Talia Smith)

Last year nearly 80 diseased ash trees were removed from the park in which the green beetle had staked its first claim in Minneapolis. I anticipated seeing the Witch’s Hat on a bald head. Not so. Other species, especially the old oaks, make the absence of ashes barely noticeable. Several new trees had been planted, but the vegetation around the hill and tower is very dense. Given the weather of the last few months, the park, as well as the rest of the neighborhood, had the feel of a rain forest. The gentle mist at the time exaggerated the effect.

While in the neighborhood I wanted a closer look at the street triangles that are owned as parks by the MPRB. My recollection from visiting them a few years ago was that they were among the smallest “parks” in the city and the MPRB inventory lists Orlin Triangle (SE Orlin at SE Melbourne) as one of six triangles that measure 0.01 acres. The other one-hundredth-acre parks are Elmwood, Laurel, Oak Crest, Rollins and Sibley, all triangles; however, all but Elmwood appear to the naked eye to be considerably larger than Orlin.

Orlin Triangle measures roughly 30 feet per side. What’s remarkable about the triangle though is that it is a little garden. The unifying element of the little triangle gardens in Prospect Park is that each has one, two or three boulders.

The first record I can find of requests to have the park board take over Prospect Park street triangles was in 1908. In response to a petition from the Prospect Park Improvement Association, the park board agreed on September 7, 1908 to plant flowers and shrubbery on the triangles and care for them if the neighborhood would curb them and fill them with “good black soil,” and “obtain the consent of the City Council to the establishment of such triangles.” The triangles were apparently at that time just wide and probably muddy spots in the roads.

The association reported in November of that year that the triangles were ready for planting. There is no indication in park records of how many triangles were involved or exactly where they were. Nor is there any record of whether the park board planted the flowers and shrubs as promised, or cared for them.

The next time I can find those properties mentioned in park board proceedings is 1915 when the City Council officially asked the Board of Park Commissioners to take control of four triangles in Prospect Park, which the park board agreed to do in October, 1915. In November the board named the four after the streets on which they were located: Barton, Bedford, Clarence and Orlin. Bedford was at some point paved over and no longer exists.

The mystery triangle at Clarence and Seymour. Love the maple tree. That’s Tower Hill Park in the background.

As for Clarence Triangle, its official address is listed in the middle of a block of houses and there is no traffic triangle at the corner of Bedford and Clarence where it is supposed to be. There is a triangle, however, at Clarence and Seymour, which is considerably smaller than the 0.02 acre that Clarence Triangle is listed at. If this were a park triangle it would easily be the smallest in the park system, measuring only 20 feet per side.

Somebody must mow the grass around the little maple tree. Did MPRB plant the maple tree or did someone else? Was it the same someone elses who maintain the other triangles in Prospect Park?

The other impressive non-park triangle in Prospect Park is at Orlin and Arthur. This is a three-boulder triangle blooming with gorgeous flowers. I’m sure the rest of the park system would be honored if this, too, were an official triangle park.

These little gems of gardens are what the park founders had in mind for the park system. They didn’t imagine giant sports complexes or ball fields in parks. They imagined parks to be little places of beauty — civilizing natural beauty — which is why they agreed to make parks of small odd lots at street intersections anyway. When you see the triangle parks of Prospect Park, you will understand better the intentions of the founders of Minneapolis parks.

Somebody deserves an award for maintaining those beautiful triangles, I just don’t know who to give it to. If you do, let me know.

The runner-up for prettiest triangle is Laurel Triangle at the intersection of Laurel Ave. and Cedar Lake Road in Bryn Mawr. Whoever planted and tends that garden deserves praise too.

David C. Smith

Elusive Minneapolis Ski Jumps: Keegan’s Lake, Mount Pilgrim and Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park

The Norwegians of Minneapolis had greater success getting their music recognized in a Minneapolis park than they did their sport. A statue of violinist and composer Ole Bull was erected in Loring Park in 1897.

This statue of Norwegian violinist and composer Ole Bull was placed in Loring Park in 1897, shown here about 1900 (Minnesota Historical Society)

A ski jump was located in a Minneapolis park only when the park board expanded Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park in 1909 by buying the land on which a ski jump had already been built by a private skiing club. The photo and caption below are as they appear in the annual report of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners for 1911.* While the park board included these photos in its annual report, they are a bit misleading. Park board records indicate that it didn’t really begin to support skiing in parks until 1920 — 35 years after the first ski clubs were created in the city.

Minneapolis, the American city with the largest population of Scandinavians, was not a leader in adopting or promoting the ski running and ski jumping that originated in that part of the world. Skiing had been around for millenia, but it had been transformed into sport only in the mid-1800s, around the time Minneapolis was founded. Ski competitions then included only cross-country skiing, often called ski running, and ski jumping — the Nordic combined of today’s Winter Olympics. Alpine or downhill skiing didn’t become a sport until the 1900s. Even the first Winter Olympics at Chamonix, France in 1924 included only Nordic events and — duh! — Norway won 11 of 12 gold medals.

The first mention of skiing in Minneapolis I can find is a brief article in the Minneapolis Tribune of February 4, 1886 about a Minneapolis Ski Club, which, the paper claimed, had been organized by “Christian Ilstrup two years ago.” That article said the club “is still flourishing.” Eight days later the Tribune noted that the Scandinavian Turn and Ski Club was holding its final meeting of the year. The two clubs may have been the same.

Ilstrup was one of the organizers two years later of one of the first skiing competitions recorded in Minneapolis, which was described by the Tribune, January 29, 1888, in glowing and self-congratulatory terms.

Tomorrow will witness the greatest ski contest that ever took place in this country. For several years our Norwegian cultivators of the noble ski-sport have worked assiduously to introduce their favorite sport in this country, but their efforts although crowned with success, did not experience a real boom until the Tribune interested itself in the matter and gave the boys a lift.

The Tribune mentioned the participation in the competition of the Norwegian Turn and Ski Club, “Vikings club” and “Der Norske Twin Forening.” The Tribune estimated that 3,000 spectators watched the competition held on the back of Kenwood Hill facing the St. Louis Railroad yard. Every tree had a dozen or so men and boys clinging to the branches, while others found that perches on freight cars in the rail yard provided the best vantage point.

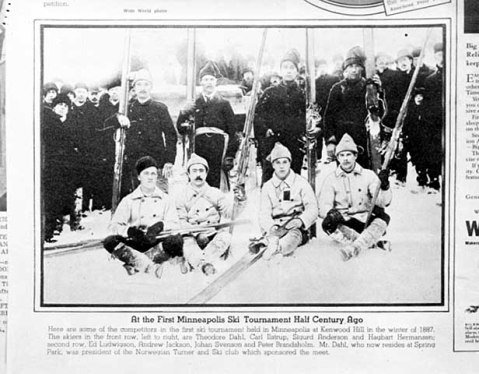

The caption for this photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Visual Resource Database claims the photo is from the winter of 1887, but was almost certainly taken at the ski tournament held on Kenwood Hill late that winter in February, 1888.

The competition consisted of skiers taking turns speeding downhill and soaring off a jump or “bump” made of snow on the hill. Points were awarded for distance and for style points from judges.

The winners of the competition were reported as M. Himmelsvedt, St. Croix Falls, whose best jump was 72 feet, and 14-year-old crowd favorite Oscar Arntson, Red Wing, who didn’t jump nearly as far, but jumped three times without falling. Red Wing was a hot bed of ski-jumping, along with Duluth and towns on the Iron Range. (The winner was perhaps Mikkjel Hemmestveit, who along with his brother, Torger, came from Norway to manufacture skis using highly desirable U.S. hickory. The Hemmestveit brothers are usually associated with Red Wing skiing, however, not St. Croix Falls.)

A Rocky Start

Despite the enthusiasm of the Tribune and the crowds, skiing then disappeared from the pages of the Tribune until 1891, when on March 2, the paper reported on a gathering of thirty members of the Minneapolis Ski Club at Prospect (Farview) Park. “This form of amusement is as distinctively Scandinavian as lutefisk, groet, kringles and shingle bread,” the Tribune reported. “With skis on his feet a man can skim swiftly over the soft snow in level places, and when a slope is convenient the sport resembles coasting in a wildly exhilarating and exciting form,” the report continued. The article also described the practice of building snow jumps on the hill, noting that “one or two of the contestants were skilful enough to retain their equilibrium on reaching terra firma again, and slid on to the end of the course, arousing the wildest enthusiasm.”

The enthusiasm didn’t last once again. The Tribune’s next coverage of skiing appeared nearly eight years later — but it came with an explanation:

During recent winters snow has been a rather scarce article. A few flakes, now and then, have made strenuous efforts to organize a storm, but generally the effort has proven a failure. The heavy snow of yesterday was so unusual that it is hardly to be wondered at that there arose in the breasts of local descendants of the Viking race a longing for the old national pastime, skiing…The sport of skiing was fostered to a considerable extent in the Northwest, and particularly in this city, a few years ago, but the snow famine of late winters put a damper on it.

— Minneapolis Tribune, November 11, 1898

The paper further reported that the “storm of yesterday had a revivifying effect upon the number of enthusiasts” and that the persistent Christian Ilstrup of the Minneapolis Ski Club was arranging a skiing outing on the hills near the “Washburn home” (presumably the orphanage at 50th and Nicollet). The paper also reported that while promoters of the club were Norwegian-Americans, “they do not propose to be clannish in the matter.”

Within a week of that first friendly ski, Continue reading

The Mother of All Minneapolis Golf Courses: Bryn Mawr II

When the golf and social activities of the Bryn Mawr Club shifted to the newly opened Minikahda Club at Lake Calhoun in July 1899, the Bryn Mawr golf course and club house didn’t stand empty for long. Two weeks after the Minikahda Club opened—and promptly became the hub of Minneapolis social life—golfers were already at work to get back on the Bryn Mawr links.

The Minneapolis Tribune on August 9, 1899 attributed the interest in reviving a golf club at Bryn Mawr to “young businessmen who find the Minikahda links at too great a distance from the city.” The paper speculated that the organizers of the new club also expected that the links could be used “at comparatively little expense.” A meeting of those interested in organizing the new club was announced at the West Hotel.

The Mother of All Minneapolis Golf Courses: Bryn Mawr I

The first golf course in Minneapolis was not Minikahda. A year before Minikahda opened, many of its members, Minneapolis’s highest society, played at a course much closer to the central city. The first Minneapolis golf course and club were in Bryn Mawr. The course didn’t last long, a little more than 10 years, but it did spawn two of the more famous golf courses in Minnesota: Minikahda and Interlachen.

When I discovered Warren Manning’s proposal for a public golf course at The Parade in 1903, I became curious about the first golf played in Minneapolis. I wanted to know what led up to the park board creating the first public golf course at Glenwood (Wirth) Park in 1916. I was surprised to learn about courses, or plans for them, at four locations in the city by 1900. The only one that still exists is Minikahda, which overlooks Lake Calhoun.

The first mention I can find of a golf course in Minneapolis — St. Paul already had Town and Country just across the Mississippi River at Lake Street — was in a Minneapolis Tribune article from April 23, 1898, which noted that twenty men who were interested in golf and wanted links closer than Town and Country had met at the West Hotel on Hennepin Avenue for the purpose of forming a Minneapolis golf club. The paper reported, “The grounds proposed are in Bryn Mawr and the high land west, ideal in location and well adapted to links, with sufficient hazards to make the game interesting.” The article also mentioned that the course was advantageously placed near the streetcar line, which ran out Laurel Avenue.

Less than two weeks later, the Tribune reported that the Minneapolis Golf Club had been formally organized, the links were almost ready for play, and a greenskeeper—Scottish, of course—had been hired away from the Chicago Golf Club in Wheaton, Illinois. He called the new course the “best inland links he had seen,” according to a Tribune article a few days later.

Golfing at Bryn Mawr in 1898. (Photo from Visual Resources Database at Minnesota Historical Society, mnhs.org.)

Golf duds at the turn of the century.

The Bryn Mawr clubhouse was formally opened on June 18. The Tribune reported the next day that several hundred people attended. “An orchestra greeted the visitors with music,” wrote the Tribune, “and there was a stream of handsome turnouts over the Laurel avenue bridge, bringing the women in their lovely summer frocks to smile on the men in their gay golfing suits.”

The nine-hole course measured a bit over 2300 yards with only two holes longer than 300 yards. The first tee was west of the clubhouse and the first green was on the east side of Cedar Lake Road. The second green was across that highway and a small pond.

Par for the course, at that time referred to as “bogey,” was set at 45 strokes. That must have seemed an impossible achievement for club members, based on early scores. At the first handicap tourney on the day the clubhouse opened, Martin Hanley beat a field of 40 golfers for the prize of a box of gutta percha balls. His net score was 101. Adding his handicap of 30, he had actually played the course in 131 strokes! That’s not three over par, it’s nearly three times par. The game was young. Hanley remained one of the club’s top golfers after the club moved to Minikahda.

It’s worth noting that the most thorough description of the new course and club appeared on May 15, 1898 in the Tribune’s society column, not its sports pages. The list of the first 200-plus members reads like a who’s who of early Minneapolis society: Pillsbury, Peavey, Heffelfinger, Jaffray, Rand, Lowry, Bell, Dunwoody, Christian, Morrison, Koon, Loring. The original plan was to admit 150 men and 100 women as members, but the initial number of female applicants was a bit lower than expected at only 62.

The new club had not only a course and greenskeeper, but a club house. The Woodburn residence had been “secured” for that purpose. The clubhouse featured “capacious rooms” and “broad verandas” and was being renovated to provide locker rooms and a restaurant. The location of the clubhouse is indicated by a report in the Saint Paul Globe of July 27, 1898 of a fire at the “quarters of the Bryn Mawr Golf club at the rear of 95 Elm Street.” Elm Street was later renamed Morgan Avenue North. So what was then 95 Elm Street would now likely be in Bryn Mawr Meadows—but that was more than ten years before Bryn Mawr Meadows was a park. The Globe reported that the total loss from the fire was not expected to exceed $200, so it was not likely a factor in the decision of the club to build a new clubhouse in a new—and now famous—location the next year.

Over the winter the members of the Bryn Mawr golf club must have become dissatisfied with the course or clubhouse or both, because the membership built a new golf course and a much grander clubhouse near the western shore of Lake Calhoun, the Minikahda Club.

On June 25, 1899 the Minneapolis Tribune reported, “Although somewhat late in starting its tournament season, the golf club which is now using the Bryn Mawr links until the Minikahda links are completed, had its tournament yesterday afternoon.” Some of the golfers at the club must have been quick learners, because early in the club’s second season scores had dropped dramatically. C. T. Jaffray won the opening tournament with a score of 85. The Tribune noted that the club was looking forward to the opening of the Minikahda clubhouse in “about three weeks.”

Roughly on schedule, the Tribune announced on July 14, “the activities that have centered around the Bryn Mawr links since the first of the season will be transferred tomorrow afternoon to the Minikahda links…The new club house on the west shore of Lake Calhoun is practically finished.”

The Minikahda clubhouse overlooking Lake Calhoun. The club’s boathouse was removed several years later when the club and other land owners along Lake Calhoun donated land for a parkway along the shore.

That was not the end of the Bryn Mawr golf links, but before it was resurrected another Minneapolis golf course emerged. “The Camden Park golf club has been organized among the young men in the employ of the C. A. Smith Lumber company,” the Minneapolis Tribune reported on July 21, 1899. The new club had a membership of 25 and growing. “It plays over a beautiful course of nine holes laid out in the Camden park region and crosses the creek three times,” wrote the Tribune. The reference must have been to Shingle Creek.

As with the Bryn Mawr course, it is not clear that the club owned the land on which it had laid out its holes. Although the Tribune noted that the new club was “particularly fortunate in its course” and that the club “anticipates becoming a large and influential organization some day,” this article is the only mention I can find in Minneapolis newspapers of a golf course in north Minneapolis. A description of the course was included in Harper’s Official Golf Guide published in 1901, with distances and “bogey” for nine holes and the clubs officers. Based on newspaper descriptions of a course that crossed a creek, the course was perhaps laid out on land that became part of Camden (Webber) Park when the park board acquired land for that park in 1908.

Next: The Mother of All Minneapolis Golf Courses: Bryn Mawr II. A new Bryn Mawr Golf Club leads to yet another famous club.

David C. Smith

Comments (1)

Comments (1)