Archive for the ‘Charles M. Loring’ Tag

Accept When Offered: A Brief History of Minnehaha Parkway

Given recent discussion of the history of Minnehaha Parkway, I thought it might be useful to consider a brief timeline of when and why the parkway was acquired by the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners and how it was developed. I wrote some of this for the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board in 2008, but it is not presently accessible at minneapolisparks.org. Most other individual park histories, such as Minnehaha Park and Minnehaha Creek Park (the creek west of Minnehaha Parkway to Edina), are available there under the “History” tab on each park page. I would encourage you to read them.

Park board records do not reveal the origin of the idea of a parkway along the valley of Minnehaha Creek. The first mention of a park along the creek is in the park board proceedings of October 8, 1887 when, after hearing from “interested parties,” the park board resolved that when lands along Minnehaha Creek “are offered, they be accepted” between Lake Harriet and the Soldier’s Home. (The Soldier’s Home was then planned to be built at the mouth of Minnehaha Creek on the Mississippi River on land donated to the state by the city. Minnehaha Falls was not yet a park, although it was in the works.) As part of the resolution, the park commissioners expressed their intent to create a parkway beside the creek when they deemed best to do so—meaning if they ever had the money.

An early 1900s postcard image of the parkway and path at an unknown location. Don’t you want to follow that path? It’s a favorite image I included in City of Parks: The Story of Minneapolis Parks

Today Minnehaha Parkway begins at Lake Harriet Parkway on the south shore of Lake Harriet and Continue reading

Commemorating the “Great War” in Minneapolis Parks: Cavell, Pershing, Longfellow, an Airport and a Memorial Drive

As we remember the war that didn’t end all wars, which ended 100 years ago this weekend, I searched through my archives for park stories related to World War I. I found several that are worth sharing. I also wanted to make available the history of Victory Memorial Drive, created in the aftermath of that horrific war, which I wrote for the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.

When the deadliest of all wars began, an English non-combatant nurse was an early casualty. The story of Edith Cavell soon was known around the world. She was so famous that a Minneapolis school, then park, were named for her. Read the story of Cavell Park and a follow-up story with photos and a comment.

Minneapolis parks also commemorate the most famous American soldier of that war, the commander of American forces, Gen. John “Blackjack” Pershing, for whom Pershing Park is named.

I’ve also re-published the story of how today’s Longfellow Field , the second property with that name, was created when the first Longfellow Field was sold to a munitions maker during the war. Also included in that post is a sidebar on how the Minneapolis airport, owned and developed by the Minneapolis Park Board, was named Wold-Chamberlain Field for two young pilots from Minneapolis who died in France during the war.

Finally, I’ve published below the story of how Minneapolis created a memorial drive in honor of Americans who had died serving their country through World War I. Many of us still know that parkway as Victory Memorial Drive, even though its official name has been Memorial Parkway for 50 years.

Victory Memorial Drive or Memorial Parkway

The parkway was originally named Glenwood-Camden Parkway when the land was acquired for the parkway in 1911, referring to its route from Glenwood Park to Camden Park. (Before the name was adopted it was referred to informally as North Side Parkway.) It was officially named Victory Memorial Drive in 1919 and included all of Memorial Parkway, what is now Theodore Wirth Parkway and Cedar Lake Parkway. The name was changed to Memorial Parkway in 1968 and applies only to the parkway from Lowry Avenue to Webber (Camden) Park. In 2010, the park board approved the use of Victory Memorial Drive again as a renovation and a 90th anniversary celebration were planned. The parkway now contains 75.23 acres.

The idea of a parkway encircling the city, today’s Grand Rounds, is nearly as old as the park board itself. When landscape architect Horace Cleveland submitted to the first park board his formal “suggestions” for a system of parks and parkways in 1883 he envisioned parkways connecting major parks in each section of the city. His original vision for a system of parkways was largely achieved decades later, although most of those parkways ended up being further from the center of city than Cleveland would have liked.

The first suggestions for a parkway in northwest Minneapolis came in 1884 when commissioners proposed a parkway around the western shore of Cedar Lake and from there through north Minneapolis to Farview Park. Some commissioners thought this was a more scenic and certainly less expensive route for a parkway into north Minneapolis than a direct route form Loring Park to Farview Park along Lyndale Avenue North. The western route had the advantage that the owner of considerable land west of Cedar Lake and in north Minneapolis, William McNair, had offered to donate land for a parkway.

Recognizing that the best route for that parkway would actually pass outside of Minneapolis city limits into what is now Golden Valley, the park board even went so far as to introduce a bill to the state legislature in 1885 that would give the park board the power to acquire land outside the city limits. The legislature granted that power to the park board.

In the summer of 1885, the park board arranged a meeting with McNair, a close friend of several of the first park commissioners, to acquire a strip of land 150-feet wide for the parkway. Charles Loring, the president of the park board then, wrote in 1890 that ultimately the board rejected McNair’s offer of free land because the route around Cedar Lake was too far from the city. McNair died in the fall of 1885 and the matter was not pursued. (Many years later the park board had discussions with McNair’s heirs about acquiring that land once again, but other than the purchase of some of McNair’s land along Cedar Lake, nothing came of the those discussions.)

The idea of a parkway around the city was revived by park commissioner William Folwell in 1891, after the acquisition of the first sixty acres of Saratoga Park, which would eventually be renamed Glenwood Park, then Theodore Wirth Park. In a special report to the board on park expansion, Folwell urged the board not to limit parkway development to the southwestern part of the city around the lakes. Giving the credit for the idea to his friend Horace Cleveland, Folwell proposed a parkway around Cedar Lake, through the new Saratoga Park to a large northwestern park, then across the city to another large park in northeast Minneapolis, continuing down Stinson Boulevard to the Mississippi River at the University of Minnesota, and then along the river to Minnehaha Park. Folwell suggested the parkways could be called the “Grand Rounds.”

The idea—and the name—struck a chord, but before the park board could build the connecting parkways, it needed the anchoring parks. And those would take many years to acquire. Keeping the idea of a northwestern parkway alive, Folwell wrote in 1901 that “but for the sudden deaths of two public-spirited citizens, the Hon. W.W. McNair and the Hon. Eugene M. Wilson, the grand rounds would long since have been extended from Calhoun to Glenwood Park and thence along the west boundary of the city to the north line.”

The idea of the northwestern parkway came up again in 1909, after the board had expanded Glenwood (Wirth) Park from its original sixty-six acres to more than eight hundred acres and also acquired Camden (Webber) Park in north Minneapolis. The park board had acquired Columbia Park in northeast Minneapolis less than two years after Folwell’s proposal. With parks to connect, the desire to build parkways between them took on new urgency.

At the end of 1909, the park board asked park superintendent Theodore Wirth to prepare plans for a parkway from Glenwood Park to Camden Park. The following year, July 21, 1910, the park board designated land for the parkway, on the condition that residents of the area would not request improvements on the land for some years, except for opening a road from 19th Avenue North (Golden Valley Road) into Glenwood (Wirth) Park. With only that stretch of road completed residents of north Minneapolis would have a parkway connection to the lakes in south Minneapolis and Minnehaha Park beyond. The only controversy surrounding the location of the new parkway, which was through open farmland, was whether the east-west section should follow 43rd Avenue or 45th Avenue. The preference expressed by the Camden Park Commercial Club for 45th Avenue seemed to resolve the issue for the board.

A total of 170 acres were acquired for the parkway at a cost of nearly $170,000. The parkway on the western city limit was 333-feet wide and the east-west section on 45th Avenue was 200 feet wide. The cost of the land for the parkway, along with land for the expansion of Glenwood Park and the purchase of the west shore of Cedar Lake, a total of $350,000, was paid for partly with bonds—30%—and the remainder with assessments on property deemed to be benefited by the new parkway.

Construction of the parkway, in keeping with promises that it would take some time, began in 1913 when the parkway was built from 16th Avenue North to 19th. The next stage of the parkway from 19th to Lowry Avenue was begun in 1916, but due to spending constraints during World War I, it wasn’t completed and opened to traffic until 1920. Park superintendent Theodore Wirth called the parkway “one of the most impressive parts of the Grand Rounds system.” In the 1916 annual report, Wirth presented plans for completing the parkway north of Lowry Avenue, then east to Camden (Webber) Park. Noting that “the country traversed is rather uninteresting,” Wirth proposed a straight parkway on the west side of the land, leaving space on the east side of the parkway for playgrounds and athletic fields.

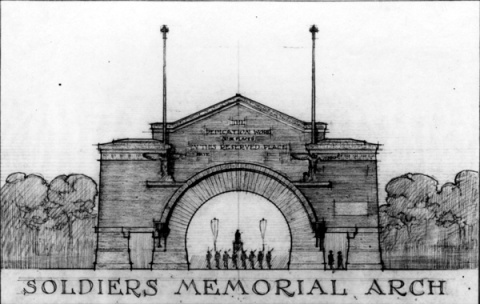

Wirth altered his plans for the parkway in 1919 when former park board president Charles Loring made a generous offer to the park board. Loring had already donated to the park board the recreation shelter in Loring Park and had paid for the construction of an artificial waterfall flowing into Glenwood (Wirth) Lake. Loring had long desired to create a memorial to American soldiers. In 1908 he had commissioned a young Minneapolis architect, William Purcell, to design a memorial arch dedicated to soldiers. Where he hoped to place the arch is not known. But in the wake of World War I, Loring proposed another kind of monument; he would plant memorial trees to soldiers along the city’s parkways. Wirth had a better idea. He thought the planned Camden-Glenwood Parkway was the ideal place to plant rows of stately elm trees as a memorial. Loring liked the idea and agreed to pay for the trees and fund a $50,000 trust account for their perpetual care. The result was a memorial drive, with the parkway centered on the strip of land, instead of off to one side.

The board accepted Loring’s offer, named the new parkway Victory Memorial Drive, and Wirth set out to find the perfect tree. He found a type of elm, called the Moline elm, in nurseries in Chicago and New York, and brought them to the park board’s nursery at Glenwood (Wirth) Park in 1919, so they would be well-established for replanting along the parkway when it was finished.

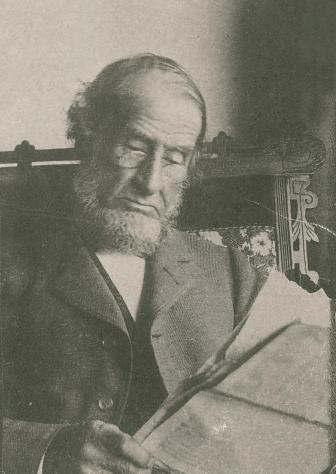

With memorial trees ready to be planted, and an additional 5.3 acres of land acquired for a monument at the northwest corner of the parkway, the final three miles of the Victory Memorial Drive were completed in 1921. On June 11, 1921 the new parkway, and its news trees, were dedicated in a grand ceremony. Loring, then age 87, was not healthy enough to attend, but drove over the new parkway the day before with his old friend William Folwell.

Later that year both General John Pershing and Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the French commander of Allied forces during World War I, visited the parkway and expressed their admiration for the living memorial. The name of each soldier from Hennepin County who had died in war was placed on a wooden cross in front of a tree. Unfortunately the special elms selected for the drive weren’t hardy enough for Minnesota’s winters and were replaced in 1925.

The wooden crosses were replaced as well in 1928, on the tenth anniversary of the end of World War I, when bronze crosses and stars, each inscribed with the name of a soldier, were installed.

The original wooden flag pole installed as a monument where the northbound parkway turns east at 45th Avenue was replaced by a bronze flag pole and ornamental base in 1923 by the American Legion of Hennepin County. A statue of Abraham Lincoln, a replica of St. Gaudens’ famous sculpture, was installed at the intersection in 1930.

In November 1959, the park board received a scare when consultants hired by the Hennepin County Board recommended that the county take over the parkway for the purpose of creating a county highway. The park board registered its opposition to the proposal in early 1960, as did the Veterans of Foreign Wars, who opposed the “desecration” of memorials to soldiers.

While the conversion of Memorial Parkway into a freeway appears not to have been seriously considered, two years later the board still included Victory Memorial Drive among parks and parkways that could be reduced or lost to freeways. During the 1960s and after when freeways were built across the city, the park board did lose two parks (Wilson Park and Elwell Park) and parts of several more to freeways. But all of those losses were for interstate freeways, not county highways.

Many of the majestic elms in two rows beside the parkway succumbed to Dutch Elm disease in the 1970s and after. Now a less uniform growth of a variety of trees covers the parkway with shade.

The parkway, flag plaza and monuments were renovated prior to the 90th anniversary of the dedication of the parkway and monuments in 2011. Eight intersections across the parkway were vacated, trails were repaved, and new lighting was installed.

Impact on Recreation Programs

One other impact of WWI on parks in Minneapolis as elsewhere was an increase in recreation programming as part of a national reponse to the alarmingly poor physical condition of so many young men who entered the U.S. Army. It was thought that better recreation programs might make the army’s training tasks somewhat easier. The subject might be worth a bit of research someday.

David C. Smith

Charles Loring’s Memorial Arch

In 1908 Charles Loring commissioned young architect William Gray Purcell to design a memorial arch. That project, revealed in Purcell’s papers at the Northwestern Architectural Library (a fabulous historical resource at the University of Minnesota), was a mystery to me. Where was this memorial arch supposed to be located?

This “presentation rendering” created by William Gray Purcell for Charles Loring is from the UMedia Digital Archive. Additional information on the William Gray Purcell Papers can be found by following the above link — as well as this one from organica.com and Mark Hammons.

I might have found the answer to the location last year when I helped create a record of the archival documents being sent from the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board to the Minneapolis Central Library for permanent archiving and public access. Continue reading

Defining Wirth

The Minneapolis Park Board and Hennepin County Library report that we are probably only weeks away from the transfer of the park board’s historical archives to the downtown Minneapolis library. A valuable trove of historical information will be preserved, protected and made available to the public as never before.

Theodore Wirth outside the house built by the park board at Lyndale Farmstead in 1910. This 1927 Christmas card was found in the park board files moved from the City Hall clock tower to park board headquarters to prepare them for their imminent transfer to the Hennepin County Library. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

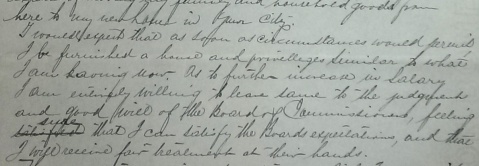

Among the more intriguing documents discovered in preparing those archives for transfer to a better place was a letter from Theodore Wirth to Charles Loring, July 4, 1905, after Wirth visited Minneapolis to consider taking the position of Superintendent of Parks. Upon returning to his home in Hartford, Connecticut, where he held a similar position, Wirth wrote to thank Loring for his hospitality and, more importantly, to outline his terms for accepting the position in Minneapolis.

The letter was an exciting discovery because for many years I and others have looked for evidence that Loring and the park board had agreed in 1905 to build a house for Wirth. That house was eventually built in 1910, four years after Wirth came to Minneapolis, at Lyndale Farmstead on Bryant Avenue near Lake Harriet. Theodore Wirth lived in the house until 1945, ten years after he retired as park superintendent. It was occupied by succeeding superintendents from then until David Fisher moved out of the house to one of his own choosing in the mid-1990s. The house became the residence of the superintendent once again in 2010, however, when Jayne Miller chose to live there when she moved to Minneapolis.

The construction of a house on park property for Wirth was very controversial in 1910. The park board’s authority to build it was challenged in court. The park board justified its decision in part by claiming that the structure was not just a residence, but an administration building—and also claimed that the house fulfilled a condition of Wirth’s employment years earlier.

Although park board plans to build the house as a residence for Wirth survived a court challenge—by a split vote in the Minnesota Supreme Court—historians, including me, had found no proof that the park board had agreed to provide housing for Wirth. I had seen a copy of Wirth’s five-page letter from 1905 proposing the terms of his employment, but the pertinent portions of that copy were utterly illegible. Now, we can read them in Wirth’s original ink.

In his July 4, 1905 letter Wirth wrote that among his conditions for accepting the park superintendent’s job in Minneapolis, “I would expect that as soon as circumstances permit I be furnished a house and privileges similar to what I am having now.” As superintendent of parks in Hartford, Connecticut, Wirth and his family lived on the second floor of a large house that stood on land donated as a park to Hartford. The ground floor of that house served as a concession stand and visitors center. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

In a subsequent letter to Loring, Wirth wrote that while he was torn between staying in Hartford or moving to Minneapolis, he had stated his terms for accepting the Minneapolis job and the park board had agreed to them, so he felt honor-bound to accept the new job. That is as close as we can get, without seeing Loring’s actual response to Wirth, to knowing that Loring and the park board had agreed to meet Wirth’s expectation of a house.

Why had the original letter been missing for so long? We found it in a file of park board correspondence not from 1905, but 1911! No one ever would have looked for it there. I suspect it was filed there after the court case had been decided and the supporting documents were no longer needed and were thrown into a current file. It probably hadn’t been looked at between 1911 and last summer.

Proper Attribution: A Park within a Half-mile of Every Residence?

Another discovery of interest to me in the documents soon to take up permanent residence at the library was a memorandum from Wirth that sheds light on the often-repeated claim that he championed a playground within a half-mile of every residence in the city.

The attribution of that claim to Wirth often presumes that he not only supported it but that it originated with him. I have scoured Wirth’s writing and the park board’s published records for the source of that particular measure for playground location. No luck. I couldn’t find that standard proposed by Wirth even in the hundreds of pages he wrote for his annual reports.

The only similar claim I was able to find was in the autobiography of Wirth’s son Conrad, who was the director of the National Park Service 1951-1964. In Parks, Politics and the People, published in 1980, more than 30 years after his father’s death, Conrad associated the “park within a half mile” concept with his father.

Then came the deep dive into once dusty archive boxes. A 1916 committee file contained many petitions signed by residents of south Minneapolis asking for a park at 39th and Chicago — what eventually became Phelps Field. Theodore Wirth submitted his opinion to a joint committee considering the issue. He opposed the playground because it was within the district already served by Nicollet (Martin Luther King) Field and Powderhorn Park. He explained,

“It is conceded by playground authorities from all parts of the country that one good-sized playground per square mile of city area is sufficient for even densely populated districts.”

That hardly seems the statement of a man who had created the standard. While I have not researched the subject on a national scale to see where the standard did originate, it appears that the park per square mile standard was already widely used. Keep in mind that Minneapolis was fairly late to the practice of establishing playgrounds under the auspices of a park board, so it was an unlikely pioneer in developing standards for playground locations. To the credit of Minneapolis and Theodore Wirth, however, Minneapolis probably came closer to meeting that standard eventually than almost all other cities.

By the way, the park board did not take Wirth’s advice in this instance and approved the acquisition of Phelps Field despite its proximity to other playgrounds and the large amount of grading that Wirth asserted would be required to make the land into usable playground space.

Hundreds more documents, like these, that provide information and insights into the creation and evolution of Minneapolis’s parks will soon be available to everyone at the library.

Congratulations!

The transfer of the park board archives culminates the work of several years. Park commissioners, led by Scott Vreeland, superintendent Jayne Miller, and park board staff, especially Dawn Sommers and former real estate attorney Renay Leone, deserve thanks for their commitment to preserving park historical records. The project also owes a great deal to the cooperation of Josh Schaffer in the City Clerk’s office, and Ted Hathaway, director of Special Collections at Hennepin County Library.

I would encourage local historians, especially those with an interest in the first half of the 20th Century, as well as park enthusiasts, to take a look at the archives once Ted and his staff at the library can make them available. They provide a fascinating historical view of not just a park system, but a city.

David C. Smith

What were the first two names for Loring Park?

A comment received today from Joan Pudvan on the “David C. Smith” page made me think of some little known facts in Minneapolis park history. So here’s your park trivia fix for today.

Joan asked if Loring Park was once named Central Park? Joan is a post card collector and has seen many post cards from the early 1900s labelled “Central Park.” Those cards feature images of what we know is Loring Park, so the answer to Joan is, “Yes.” When did the name change?

Central Park officially became Loring Park in 1890 when the park board’s first president, Charles Loring, was leaving the board. He, along with every other Republican on the Minneapolis ballot that year, had been defeated at the polls in a shift of political power. At the end of Loring’s tenure, his friend and fellow park advocate, William Folwell, proposed renaming Central Park for the man who had helped create it, and had even supervised much of the landscaping in the park (to H.W.S. Cleveland’s design). Loring said he would prefer that the park be named Hennepin Park for its location on that avenue, but the rest of the board agreed with Folwell that Loring should be honored. So the name was changed, a fact that the post card publishers hadn’t caught up with as many as ten or fifteen years later.

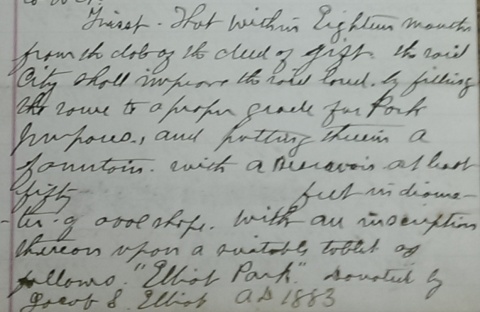

Loring was not, however, the first person to have a Minneapolis park named for him. That distinction goes to Jacob Elliot who, in 1883, donated his former garden to the city as Elliot Park. Elliot had been a prominent doctor in Minneapolis who had retired to Santa Monica, California. The handwritten document (as all were at that time) donating the land to the city as a park — recently discovered in a park board correspondence file — was signed by Wyman Elliot as the attorney-in-fact of his father Jacob Elliot. Wyman Elliot later became a park commissioner himself, when he was elected to fill out Portius Deming’s term from 1899-1901 after Deming was elected to the Minnesota legislature.

In the document that officially donated the land, the most interesting paragraph required the creation, within 18 months, of a fountain in the park with a reservoir “of oval shape” with a diameter of at least 50 feet.

One condition of Jacob Elliot’s donation of land for Elliot Park in 1883 was the creation of fountain. Elliot Park was the first Minneapolis park named for a person. The clause pictured is a part of the original document donating the land. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Additional recently found correspondence sought Dr. Elliot’s approval for the plaque he had specified.

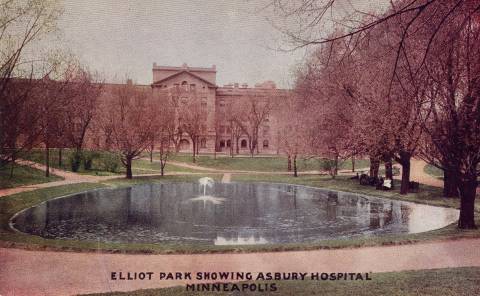

The fountain built as a condition of the donation of Elliot Park. From a postcard published around 1910. The “fountain” was a single standpipe in the middle of the pond. The Elliot Park pond was very similar to the one created in Van Cleve Park in the early 1890s.

Elliot Park fountain and Asbury Hospital from a post card with an eerie pink tinge. A soccer field now occupies this section of the park.

One other bit of naming trivia before we get to the other name for Central/Loring Park. In 1891, Judson Cross, one of the first 12 appointed park commissioners, wrote to the park board suggesting that the pond in Loring Park be named Wilson Pond for Eugene M. Wilson, one of the first and greatest park commissioners. He also served as the board’s attorney in the 1880s. He had also been elected to Congress and as Mayor of Minneapolis twice. He died at age 56 in 1890 in the Bahamas where he had gone to try to regain his health. Cross claimed that the name was appropriate because Wilson had been the strongest advocate of securing the land surrounding what had once been Johnson’s Pond for the park that became Central Park. Wilson may have played one of the most important roles in creating a park system in Minneapolis because he was one of the most prominent Democrats to strongly favor the creation of the park board. Without Wilson’s influence among Democrats, many of whom opposed the Park Act — the Republican Party supported it — Minneapolis voters may not have passed the act in the April 1883 referendum.

The board did not add Wilson’s name to Loring Park, but it did rename nearby Hawthorne Square, Wilson Park — which was particularly appropriate because Eugene Wilson’s home faced that park. Unfortunately, the park was wiped out for the construction of I-94 in 1967, so we have been without Wilson’s name in our park system for nearly 50 years.

The other name by which Central and Loring Park was known lasted only a month. In 1885, the park board voted to name the park Spring Grove Park. Without much explanation, but apparently in the face of considerable opposition, the park board backtracked to Central Park a month later.

So…Central Park, Spring Grove Park, Loring Park. I think the park board ended up in the right place.

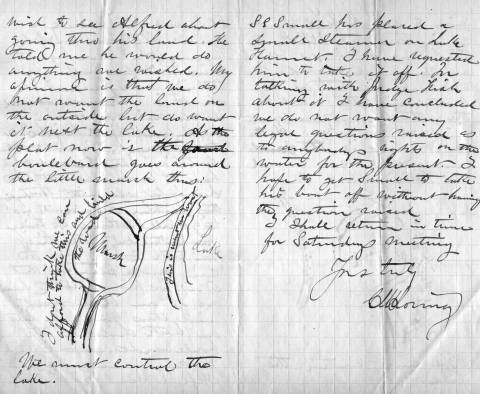

One among many reasons for that opinion is another historical document rediscovered in the last few months: a letter from Charles Loring to the board from which the excerpt below was taken. In the letter, Loring proposes to create a Memorial Drive, a tribute to fallen American soldiers, as part of the Grand Rounds. The result was Victory Memorial Drive.

Charles Loring suggested a Memorial Boulevard and pledged to create a trust fund that would provide an annual revenue of $2,500 for the perpetual care of trees along the drive. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Without any such intention when I started writing this, I have highlighted the incredible time and resources that have been donated to the Minneapolis park system. Loring, Elliot, Wilson: all people who shared a commitment to parks and were willing to give time, money and land to the city to realize their visions of what city life should be. Their example is particularly significant now as park leaders are trying to raise funds for new park developments downtown, along the river, and in north and northeast Minneapolis. Not a bad way to be remembered.

David C. Smith

Quotes from “Arts and Parks”: Folwell on Museums

Thanks to everyone who turned out Saturday morning at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts to listen to my thoughts on the people who created parks and a fine art society in Minneapolis in 1883. Special thanks to those who purchased a copy of City of Parks afterwards and introduced themselves. Thanks too to Janice Lurie and Susan Jacobsen for inviting me to speak and hosting the event. I want to remind everyone that all proceeds from the purchase of the book go to the Minneapolis Parks Foundation.

Quite a few of those who attended asked where they could find some of the quotes I used in my presentation, so I promised I would post them here. The most requested, especially from those who work with arts organizations, was William Watts Folwell’s remarks as reported in the Minneapolis Tribune at the laying of the cornerstone of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in 1913. I’ve provided an excerpt of his remarks from the July 31, 1913 issue of the newspaper, as well as quotes from Charles Loring and Horace Cleveland from earlier times as noted — most of which have appeared in other posts here over the years.

Folwell’s remarks included these observations on his hopes for the Institute:

“ The primary function of the institution will naturally be exhibition of works of art. I trust it will be the governing principle from the start that no inferior works shall ever have a place. Better bare walls and empty galleries than bad art. A single truly great and meritorious work is worth more in every way than a whole museum full of the common and ordinary. A few such works might make Minneapolis a Mecca for art lovers. Gift horses should be carefully looked in the mouth. I am almost ready to say that none should be received. Let benefactors give cash.

“The museum should appreciate and encourage the artistic side of all structures, public, domestic and industrial, and of all furnishings and appliances. ‘Decorative art’ should never be a term of disparagement here. Men have the right to live amid beautiful surroundings and to handle truly artistic implements.”

– William Watts Folwell, as reported in the Minneapolis Tribune, July 31, 1913.

Folwell was not one to mince words. It is noteworthy, especially considering his comments on decorative arts, that one of the influential people in the creation of the Society of Fine Arts and the Institute was interior designer and furniture maker John Scott Bradstreet. You can read much more about him here.

Other quotes from Horace William Shaler Cleveland:

“Regard it as your sacred duty to preserve this gift which the wealth of the world could not purchase, and transmit it as a heritage of beauty to your successors forever.”

–H.W.S. Cleveland, 1872“If you have faith in the future greatness of your city, do not shrink from securing while you may such areas as will be adequate to the wants of such a city…Look forward for a century, to the time when the city has a population of a million, and think what will be their wants. They will have wealth enough to purchase all that money can buy, but all their wealth cannot purchase a lost opportunity, or restore natural features of grandeur and beauty, which would then possess priceless value, and which you can preserve for them if you will but say the word and save them from the destruction which certainly awaits them if you fail to utter it.”

— H.W.S. Cleveland, Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis, presented June 2, 1883 to the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners.“The Mississippi River is not only the grand natural feature which gives character to your city and constitutes the main spring of prosperity, but it is the object of vital interest and center of attraction to intelligent visitors from every quarter of the globe, who associate such ideas of grandeur with its name as no human creation can excite. It is due therefore, to the sentiments of the civilized world, and equally in recognition of your own sense of the blessings it confers upon you, that it should be placed in a setting worthy of so priceless a jewel.”

– H.W.S. Cleveland, Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis“No city was ever better adapted by nature to be made a gem of beauty.”

— H.W.S. Cleveland to William Folwell, October 22, 1890, Folwell Papers, Minnesota Historical Society“I have been trying hard all winter to save the river banks and have had some of the best men for backers, but Satan has beaten us.”

– H.W.S. Cleveland to Frederick Law Olmsted on his efforts to have the banks of the Mississippi River preserved as parkland, June 13, 1889, Library of Congress.

The west bank of the Mississippi River Gorge from Riverside Park near Franklin Avenue to Minnehaha Park was not acquired as parkland until after Cleveland died.

“There does not seem to be another such place as Minneapolis for its constant demands upon the time of its citizens. Everyday there is something that must be done. I suppose, perhaps, this may be why we are a great city.”

– Charles Loring in a letter to William Windom, September 27, 1890, Minnesota Historical Society

It is worth noting that Loring was the president of the Minnesota Horticultural Society, vice president of the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, president of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners, president of the Minneapolis Improvement Association, and an officer in the Athenaeum and the Board of Trade. It could be said that he alone was one of the reasons Minneapolis was a great city.

Finally, the newspapers were active supporters of arts and parks through most of the history of Minneapolis. I pulled this quote from an editorial in the Minneapolis Tribune:

“While looking after the useful and necessary, let us not forget the beautiful.”

– Minneapolis Tribune, June 30, 1872

Words we could all live by.

David C. Smith

Horace Bushnell’s Ghost

Horace Bushnell, one of America’s most influential theologians in the 19th Century, was among the first people to promote parks in Minneapolis. His ghost may still haunt us.

I don’t know if this is really a six-degrees-of-separation story—Bushnell and Kevin Bacon couldn’t have met—but there are quite a number of coincidences involved. They center on the famous Congregational minister from Hartford, Conn. who was also known for his early advocacy of city planning. And I mean really early. 1860s.

I’ll let you do your own research on Horace Bushnell’s sermons and books on theology, but here’s a sample of what he had to say on cities in his book Work and Play; or Literary Varieties in 1864:

The peoples of the old world have their cities built for times gone by, when railroads and gunpowder were unknown. We can have cities for the new age that has come, adapted to its better conditions of use and ornament. So great an advantage ought not to be thrown away. We want therefore a city-planning profession, as truly as an architectural, house-planning profession. Every new village, town, city, ought to be contrived as a work of art, and prepared for the new age of ornament to come.

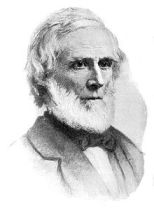

Horace Bushnell, famous preacher and theologian, encouraged Minneapolis to acquire parkland in 1859-60.

Bushnell expressed an idea well ahead of his time and also coined a phrase: this was one of the first uses of the term “city-planning.”

Of more parochial interest here is Bushnell’s advocacy for creating a park in Minneapolis. More specifically, he was the first to recommend that the towns of St. Anthony and Minneapolis acquire Nicollet Island to be a park. Only Edward Murphy, with his donation to Minneapolis of Murphy Square in 1857, can claim an earlier promotion of parks for the young city.

I only came across the story of Bushnell in Minnesota recently while investigating another subject. Sifting through old newspaper files, I found this comment from “Mr. Chute” (likely Richard, instead of Samuel) at a Minneapolis Board of Trade meeting as reported in the Minneapolis Tribune, February 3, 1874:

“Many of you remember Dr. Horace Bushnell, of Hartford, Conn., who spent a year with us in 1858-59 (sic). He was a gentleman of large heart, if not large means, who, seeing the necessity for a park in Hartford to accommodate the laboring man, whose firm friend he always was, procured and donated the ground to the city for a park, which is now the pride of that wealthy place. When Dr. Bushnell was here his constant burden was, you must secure Nicollet Island; it is a shame and a disgrace to neglect your opportunities; buy it at any price.”

I sought corroboration of Chute’s claim and found it in Isaac Atwater’s History of Minneapolis, Vol. 2. In a profile of Andrew Talcott Hale, the author was explaining that Hale came to Minneapolis from Hartford, Connecticut for his pulmonary health, inspired by the experience of Dr. Bushnell, when he provided this digression:

“While yet Minneapolis was a rural settlement, Dr. Horace Bushnell, of Hartford, Conn., visited it for the benefit of his health, impaired by serious inroads of pulmonary disease. After summering and wintering here, with excursions through out the unsettled prairies of the Dakota, during which he freely contributed by his pulpit ministrations, as well as enthusiastic advocacy of park improvements to the improvement of the morals and culture of the community, he returned to his work in Hartford apparently restored to health and vigor.” (Emphasis added.)

In the mid-1800s, Minneapolis was a destination for many people with pulmonary problems. It was thought that the dry air was a tonic for the lungs. Bushnell’s experience seems to substantiate that belief. He wrote of the Minneapolis climate,

“One who is properly dressed finds the climate much more enjoyable than the amphibious, half-fluid, half-solid, sloppy, grave-like chill of the East.”

Bushnell’s letters to his family, published in The Life and Letters of Horace Bushnell, provide some further descriptions of his life in Minnesota from July 1859 to May 1860. Among my favorite passages is this one on Lake Minnetonka:

“Well, I have talked a long yarn, telling you nothing about the Lake, the strangest compound of bays, promontories, islands and straits ever put together—a perfect maze, in which a stranger would be utterly lost.”

The advantages of Minnesota weather aside, two prominent Minneapolitans—Chute and Atwater—remembered Bushnell’s sojourn in Minnesota and they both recalled his commitment to the idea of parks in cities, Minneapolis included. He had already helped Hartford get one.

Hell without the Fire

The Hartford park referred to by Mr. Chute above was created in 1854 when Bushnell helped convince the residents of that city to approve spending more than $100,000 to purchase forty acres in the center of the city for a public park. That must have taken some doing because it was an abused, polluted tract—”tenements, tanneries and garbage dumps,” according to the Bushnell Park Foundation—that Bushnell himself called, “Hell without the fire.” It is considered the first publicly funded park in the United States.

When Bushnell returned to Hartford from Minneapolis after regaining his health in 1860, little had been done to convert the land into a useful park. So he turned to a friend and former parishioner, who at that time was considered to know something about parks. But Frederick Law Olmsted was occupied with his own park project; he was still working on his most famous creation, Central Park in New York. Pressed for a recommendation, Olmsted suggested landscape architect Jacob Weidenmann for the job.

Weidenmann was an immigrant from Winterthur, Switzerland. (Remember that.) Olmsted later wrote that the only two landscape architects in the U.S. he knew of who were qualified to advise park commissions, other than himself and his partner Calvert Vaux, were Weidenmann and H. W. S. Cleveland. Weidenmann was hired and spent eight years as superintendent of Hartford’s City Park, creating a much less formal park there than was typical in Europe. After Weidenmann’s work was done, Connecticut began building its state capitol adjacent to the park in 1872. It wasn’t until Horace Bushnell was dying in 1876 that Hartford renamed the park in his honor: Bushnell Park. He died two days later.

Meanwhile Samuel Clemens had taken up residence in Hartford in 1871 and had turned to writing fiction. His first novel, The Gilded Age, was co-written with Charles Dudley Warner, who was a Hartford park commissioner.

The Minneapolis Connection

How does this all tie back to Minneapolis? Through Theodore Wirth. As many other cities, including Minneapolis, had caught up to and passed Hartford on the park-o-meter in the 1890s, several of Hartford’s winners in the Gilded Age sweepstakes gave land to the city for parks. Albert Pope left 73 acres to the city for a park in 1894. The same year, Charles Pond left 90 acres of his estate for Elizabeth Park — his wife’s name — and threw in his house and half his fortune to maintain them. Henry Keney went Pope and Pond several hundred acres better that year and donated 533 acres for Keney Park. In 1895 the city purchased another 70 acres for Riverside Park and another 200 acres in the southern part of the city for what became Goodwin Park.

That was a lot of new real estate to whip into park shape. Hartford needed a park superintendent to manage its sudden riches. Hartford’s leaders must have had fond recollections of working with Weidenmann thirty years earlier because when they looked through applicants for the job, they picked someone from the same small town in Switzerland—Winterthur—that Weidenmann had called home. That man was Theodore Wirth.

When Wirth began the job in Hartford, his experience was mostly in horticulture, so Hartford hired Olmsted’s sons—Olmsted Sr. had already retired—as landscape architects for some of the first projects. But after a few years on the job working with the Olmsted firm, Wirth himself designed new park layouts for Elizabeth Park and Colt Park, another 100-plus acre park gift, this from the family famous for revolvers. With those park plans, Wirth established himself as a landscape architect as well as a gardener.

The only Hartford park Wirth did not manage was the enormous Keney Park, which was administered by its own Board of Trustees, separate from the Hartford park commission, and had its own park superintendent, George A. Parker. Wirth and Parker knew each other well. I believe that George Parker was likely responsible for Charles Loring meeting Theodore Wirth in 1905 when he was a committee of one of the Minneapolis park board looking for a replacement for retiring Minneapolis park superintendent William Berry. Parker was the likeliest link between Wirth and Loring because Parker was very active in the new national park organization, American Park and Outdoor Art Association, of which Loring was president 1898-1900. When Loring hired Wirth to become park superintendent in Minneapolis, Parker became the superintendent of all Hartford parks.

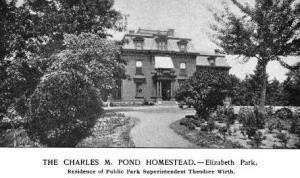

Theodore Wirth lived in the upper level of the former Pond house in Elizabeth Park in Hartford, Conn. The ground floor was open to the public. (Picturesque Parks of Hartford, 1900)

The home, at right, in Hartford’s Elizabeth Park also features prominently in an important decision in Minneapolis park history. The reason the Minneapolis park board built a residence for Theodore Wirth at Lyndale Farmstead in 1910 was to fulfill a promise made to Wirth by Charles Loring, when Loring was negotiating terms for Wirth to take the superintendent’s job in Minneapolis. Wirth had been provided housing in Elizabeth Park in Hartford and wanted a similar deal in Minneapolis. Wirth and family had lived in the upper level of the former home of Charles Pond on the estate Pond had bequeathed to the city. The ground floor and verandas of the Pond home were open to the public as shelters in the summer. The Hartford Public Library operated a small library in the building as well.

Elizabeth Park was also the site of Wirth’s earliest claim to fame: the first public rose garden in the United States, a feature he replicated at Lyndale Park near Lake Harriet in 1907.

This turn-of-the-century postcard features one portion of the extensive greenhouses of A. N. Pierson, the “Rose King,” of Cromwell, Conn. about ten miles from Hartford. In 1895 Pierson won the gold medal at the New York Flower Show for a new rose, Killarney, that was beautiful and hardy. He also won 17 firsts and two seconds. “Roses became a profit-making flower, Pierson became the Rose King and Cromwell became Rosetown,” wrote Robert Owen Decker in Cromwell, Connecticut, 1650-1990. A profile of Pierson in American Florist in 1903 speculated, “There are so many rose houses in this establishment that it is doubtful the proprietor knows the exact number.” Pierson started a dairy with 65 cows just to supply sufficient manure for his growing houses. Pierson and Wirth were both vice-presidents of the Connecticut Horticultural Society 1899-1904. I would think it quite likely that Wirth’s very successful public rose garden, established in Elizabeth Park in 1903-4, drew on the cultivating research and expertise of Pierson, too. (Postcard photo: connecticuthistory.com)

Another peculiar connection between Horace Bushnell and Minneapolis parks might be appreciated only by people who have searched for information on the “Father of Minneapolis Parks,” Charles Loring. To begin with, Loring came to Minneapolis the same winter Bushnell was here and for the same reason. Loring had an unspecified health condition—likely a pulmonary malady—that caused him to come west from his Maine home. He tried Chicago first, then Milwaukee, and finally arrived in Minneapolis in the winter of 1860. Although he often spent winters in Riverside, California, he remained a resident of Minneapolis until he died here in 1922.

But an odd link to Bushnell goes further. A young Congregational minister from Hartford, a protege of Bushnell’s, became the founder of the Children’s Aid Society of New York. He publicized widely the plight of children in New York’s slums and, finally, in an attempt to improve the lives of those children he organized what came to be known as “Orphan Trains” that sent New York orphans to better lives, supposedly, with settlers in the west. His name was Charles Loring Brace. Perhaps it is only coincidence that Loring’s rationale for creating parks and playgrounds in Minneapolis was often that children needed places to play and grow.

A final link between Minneapolis and Horace Bushnell’s long visit here. For many years, local historians have turned to a number of late 1800s-early 1900s profiles of Minneapolis that included “vanity” or “subscription” biographies of prominent citizens. One of those, A Half-Century of Minneapolis, was compiled by influential Minneapolis journalist Horace B. Hudson. You’ve probably already guessed the middle name of Mr. Hudson, who was born in 1861, shortly after Dr. Bushnell’s visit here. Yes, his full name is Horace Bushnell Hudson.

More than 150 years have passed since Horace Bushnell implored the people of the little towns on either side of St. Anthony Falls to acquire Nicollet Island as a park. Many attempts have been made, several surveys completed, many speeches delivered in favor and opposed, and part of it acquired, but it’s never become the park Bushnell imagined. Horace Bushnell’s ghost might haunt us until we get it right.

David C Smith

© David C. Smith

Those Darn Cars!

“It is the sense of this Board that the practice of tooting Automobile horns, by way of applause, at the concerts given in the parks should be discontinued.”

Motion proposed by park commissioner Charles M. Loring and adopted by the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners, June 18, 1906.

The First River Plans: Long Before “Above the Falls” and “RiverFirst”

“I have been trying hard all Winter to save the river banks and have had some of the best men for backers, but Satan has beaten us.” H. W. S. Cleveland to Frederick Law Olmsted on efforts to have the banks of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis preserved as parkland, June 13, 1889 (Letter: Olmsted Papers, Library of Congress. Photo: H. W. S. Cleveland, undated, Ramsey County Historical Society)

Considerable time, effort and expense—$1.5 million spent or contractually committed to date—have been invested in the last two years to create “RiverFirst,” a new vision and plans for park development in Minneapolis along the Mississippi River above St. Anthony Falls. That’s in addition to the old vision and plans, which were actually called “Above the Falls” and haven’t been set aside either. If you’re confused, you’re not alone.

Efforts to “improve” the banks of the Mississippi River above the falls have a long and disappointing history. Despite the impression given since the riverfront design competition was announced in 2010, the river banks above the falls—the sinew of the early Minneapolis economy—have been given considerable attention at various times over the last 150 years. There’s much more

The Statue of Liberty in a Minneapolis Park?

If you could put a replica of this statue anywhere in a Minneapolis park, where would you put it?

If you could put a replica of this statue anywhere in a Minneapolis park, where would you put it?

One of the most intriguing “might-have-beens” in Minneapolis park history was the proposed construction of a Japanese Temple on an island in Lake of the Isles. (If you missed it, read the story of John Bradstreet’s proposal.) But that was not the only proposal to spruce up an island in a Minneapolis park.

On March 15, 1961 the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners approved the placement of a replica of the Statue of Liberty on an island in another body of water.

Park board proceedings attribute the proposal to a Mr. Iner Johnson. He offered to donate and install the 10-foot tall replica statue made of copper and the park board accepted the offer — as long as the park board would incur no expense.

I can find no further information on the proposal or why the plan was never executed — or if it was, what happened to the statue.

The intended location of the statue was the island in … Powderhorn Lake.

Island in Powderhorn Lake from the southeast shore, near the rec center in 2012. The willow gives the impression of an entrance to a green cave. (David C. Smith)

The Minneapolis Morning Tribune of March 16, 1961 reported that Lady Liberty was to be installed for the Aquatennial that summer. Was it? Does anyone remember it? I’ve never seen a picture or read a description.

Another park feature from H.W.S. Cleveland

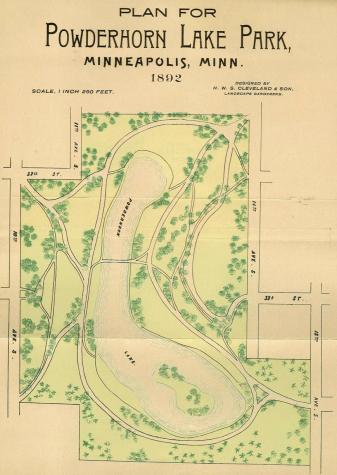

The man-made island was first proposed in the plan created for Powderhorn Park in 1892 by H. W. S. Cleveland and Son. It is the only Minneapolis park plan that carried that attribution. Horace Cleveland’s son, Ralph, who had been the superintendent of Lakewood Cemetery since 1884, joined his father’s business in 1891 according to a note in Garden and Forest (July 1, 1891).

More on Garden and Forest. Horace Cleveland contributed frequently to the influential weekly horticulture and landscape art magazine through his letters to the editor, Charles Sprague Sargent. Sargent was also the first director of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum. Click on Garden and Forest to learn more about the magazine and its searchable archive. (Thank you, Library of Congress.)

Cleveland’s plan for Powderhorn Park featured a bridge over the lake, about where the north shore is now, and an island. The plan was published in the park board’s 1892 annual report. (Horace W. S. Cleveland, MPRB)

Horace Cleveland was 78 and finding the field work of landscape architecture physically challenging when he and Ralph joined forces to produce a plan for Powderhorn. Only a year later his doctor prohibited him from working further. The Cleveland’s were paid $546 for their work at Powderhorn, but the park board didn’t implement parts of the plan for more than ten years.

Horace Cleveland had been a strong booster for making the lake and surrounding land into a park. Powderhorn Lake had been considered for acquisition as a park from the earliest days of the park board in 1883. However, the park board believed landowners in the vicinity of the lake were asking far too high a price for their land. To learn more of the park’s creation see the park board’s history of Powderhorn Park.

After I wrote that history, I found a transcript of a letter Cleveland had written to the park board (Minneapolis Tribune, July 26, 1885) encouraging the board to acquire about 150 acres from Lake Street to 35th Street between Bloomington and Yale avenues, which was, Cleveland claimed, the watershed for Powderhorn Lake. (I can find no Yale Avenue on maps of that time. Does anyone know what was once Yale Avenue?)

The letter repeated Cleveland’s frequent message about acquiring land for parks before it was developed or became prohibitively expensive. But he also claimed that due to the unique topography around the lake that if it were allowed to be developed it would become a nuisance that would be very costly to clean up.

I’ll quote a couple highlights from his argument for the acquisition of Powderhorn Lake and Park:

I am so deeply impressed with the value and importance of one section…I am impelled to lay before you the reasons …that you will very bitterly regret your failure to secure it if you suffer the present opportunity to escape.

The surrounding region is generally very level and the lake is sunk so deep below this average surface, that its presence is not suspected till the visitor looks down upon it from its abrupt and beautifully rounded banks. The water is pure and transparent and thirty feet deep, and its shape (from which it derives its name) is such as to afford the most favorable opportunity for picturesque development by tasteful planting of its banks…All the most costly work of park construction has already been done by nature.

Cleveland concluded his letter to the park board by writing,

I feel it my duty in return for the bounty you have done in employing me as your professional advisor, to lay before you this statement of my own convictions, and request, in justice to myself, that it may be placed on your records, whatever may be your decision.

On the day Cleveland’s letter was presented to the park board, the board voted not to acquire Powderhorn Lake as a park and Cleveland’s letter was not printed in the proceedings of the park board either. Still the lake and surrounding land—about 60 acres, or 40 percent of what Cleveland had initially recommended—were acquired in 1890-1891 and Cleveland was hired to create a design for the park. Cleveland’s proposed foot bridge over the narrow neck of the lake was not built, even though Theodore Wirth incorporated Cleveland’s bridge into his own plan presented in 1907. However Cleveland’s island was created in the lake in the ensuing years.

In a recap of park work in 1893, park board president Charles Loring noted in his annual report that a “substantial dredge boat was built and equipped and is ready to work” at Powderhorn Lake. “I hope the board will be able to make an appropriation large enough,” he continued, “to keep the apparatus employed all of the next season.”

Loring’s hope was really more of a wish because the depression of 1893 was already having drastic consequences for the Minneapolis economy, property tax revenues and park board budgets. Despite severe cutbacks in spending in 1894, however, the park board devoted about 20% of its $48,000 improvement budget to Powderhorn. Park superintendent William Berry reported that the dredge was active in the lake for 90 days. The result was about 1.7 new acres of land created by dredging and filling along the lake’s marshy shore. In addition, nearly 15,000 cubic yards of earth were moved from near 10th Avenue to fill low areas on the north end of the lake.

An island emerges

The next year, 1895, the island was finally created. The park board spent $10,000, one-third of its dwindling improvement budget, dredging the lake and creating the island. Another 7.3 acres of dry land were created along the lake shore and an island measuring just over one-half acre was created in the southern end of the lake.

An island being created by a dredge in Powderhorn Lake, 1895. Tram tracks were built on a pontoon bridge to carry the dredged material. The photo appeared in the 1895 annual report of the park board. Not a lot of trees around at the time. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

By 1897, the only activity at Powderhorn covered in the annual report was the “raising of the dredge boat,” which had sunk that spring, and watering trees and mowing lawns in the “finished portion” of the park. Two years later, Berry reported that the west side of the park was graded, another nine acres of lawn were seeded and 100 trees and 1600 shrubs were planted to a plan created by noted landscape architect Warren Manning. Horace Cleveland had left Minneapolis in 1896, moving with his son to Chicago, where he died in 1900.

It’s unlikely, due to his age, that Cleveland played any role in the actual creation of the island in Powderhorn Lake in 1895. And credit for the idea of an island may not be due solely to Cleveland either, but also to a coincidence in the creation of Loring (Central) Park in 1884. Cleveland’s original plan for Loring Park did not include an island in the pond then known as Johnson’s Lake. Charles Loring later told the story in his diary entry of June 12, 1884 (Charles Loring Scrapbooks, Minnesota Historical Society),

“In grading the lake in Central [Loring] Park the workmen left a piece in the center which I stopped them from taking out. I wrote Mr. Cleveland that I should be pleased to leave it for a small island. He replied that it would be alright. I only wish I had thought of it earlier so as to have had a larger island.”

The development of the island envisioned by Loring while supervising construction, then approved by Cleveland, proved to be a famous success. (The island no longer exists.) Four years later, on October 3, 1888, Garden and Forest published an article about Central (Loring) Park and concluded a glowing tribute with these words:

When it is considered that artificial lakes and islands are always counted difficult of construction if they are to be invested with any charm of naturalness, the success of this attempt will not be questioned, while the rapidity with which the artist’s idea has grown into an interesting picture is certainly unusual. The park was designed by Mr. H.W.S. Cleveland.

Given such praise, it is not surprising that Cleveland would be willing to try an island from the beginning in Powderhorn Lake. Between the time it was proposed by Cleveland and actually created three years later, decorative islands had also earned a faddish following on the heels of Frederick Law Olmsted’s highly praised island and shore plantings on the grounds of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. One landscape historian wondered whether Olmsted’s creation and treatment of his island in Chicago could have been influenced by his 1886 visit to Minneapolis where he would have seen Loring and Cleveland’s island in Loring Park.

The success of islands in Loring Pond and Powderhorn Lake likely also influenced Theodore Wirth when he proposed creating islands in Lake Nokomis and Lake Hiawatha. Both of those islands were scratched from final plans.

The island in Powderhorn Lake is one of three islands that remain in Minneapolis lakes—and the only one that was man-made. Only two of the four original islands in Lake of the Isles still exist. The two long-gone islands were incorporated into the southwestern shore of the lake when it was dredged and reshaped from 1907 to 1910. The two islands that remain were significantly augmented by fill during that period.

A handful of islands still exist in the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, although many more were flooded when the Ford Dam was built. Another augmented island—Hall’s Island—may be re-created in the near future as part of the RiverFIRST plan for the Scherer site upstream from the Plymouth Avenue bridge.

Although Horace Cleveland died in 1900, when the Minneapolis economy finally boomed again the park board voted in April 1903 to dust off and implement the rest of the 1892 Powderhorn Lake Park plan of H.W.S. Cleveland and Son.

The lake was reduced by about a third in 1925 when the northern arm of the lake was filled. Theodore Wirth, the park superintendent at the time, contended that the lake level had dropped six feet for unknown reasons after his arrival in 1906. The filled portion of the lake was converted into ball fields — a use of park land that was unheard of in Horace Cleveland’s time. The lake that Cleveland estimated at 30 to 40 acres in 1885, when he recommended its acquisition as a park, is now only a little over 11 acres.

The northern arm of Powderhorn Lake was filled in 1925. I wonder if the folks who lived in the apartments on Powderhorn Terrace had their rent reduced when they no longer had lakeshore addresses? (City of Parks, MPRB)

Now about that Statue of Liberty. Does anyone remember it in Powderhorn Lake?

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

A Challenge for Wedge and Whittier Historians

A regular reader has asked a couple questions that I can’t answer, but perhaps someone else can. Why does Lyndale Avenue South from 19th to 24th street or so seem to run in a trench with the east-west cross streets rising steeply on both sides of Lyndale. Is there a geological explanation for it?

Also, was there ever a swampy area at Franklin and Lyndale, or nearby in Whittier, that was drained for park purposes? The park board was never involved in such an action, but perhaps an effort to create a playground or other playing field could have taken that direction before the park board took responsibility for playgrounds.

In the 1880s there was a baseball stadium that seated about 1300 near 17th and Portland, according to Minnesota baseball historian Stew Thornley, but that’s quite a distance east. Horace Cleveland was likely referring to that field when he wrote to William Folwell in 1884, “There’s no controlling the objects of men’s worship or the means by which they attain them. A beautiful oak grove was sacrificed just before I left Minneapolis to make room for a baseball club.” Cleveland’s words imply a clear dividing line between parks and playing fields. At that time, the two did not mix. (Folwell Papers, Minnesota Historical Society.)

The area a couple blocks northeast of Franklin and Lyndale—south of what became Loring Park—was the site selected by Charles Loring, William King, Dorilus Morrison and others for a private cemetery in the 1860s. Land speculators got wind of the plan, however, and drove the price of the land higher than the cemetery group would pay. Instead they looked for land further south and established Lakewood Cemetery in 1871 at its present site. Charles Loring wrote in a letter to George Brackett, both were among the founders of Lakewood, that the idea for a beautiful cemetery came to Loring as he buried his infant daughter in Layman’s Cemetery in 1863. (George Augustus Brackett Papers, Minnesota Historical Society.)

(Ask me a question about Minneapolis parks and I’ll probably work Loring and Cleveland into the answer!)

Any ideas on the topography of Lyndale Avenue South? Or a drained swamp near Lyndale and Franklin or elsewhere in Whittier?

David C. Smith

Comments (2)

Comments (2)