Archive for the ‘Minneapolis Parks: General’ Category

Friday Photo: Lake Calhoun North Shore

One of my favorite photos of Lake Calhoun. The photo is undated, but I would estimate that it was taken in the late 1910s. The view indicates it was taken near the Minikahda Club on the west side of the lake looking northeast toward downtown. The photo was taken after the Lake Calhoun Bath House (center) was completed in 1912, but before a parkway was built on the west side of the lake, which occurred in the early 1920s.

Lake Calhoun’s northwest shore and Bath House in late 1910s. Photo taken from Minikahda Club. Click to enlarge. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Note how far into the lake the diving platforms were built.

One of things I like from this photo is a sense of the connection between Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun. There is some open land between them. This was taken a few years before construction began on the Calhoun Beach Club across Lake Street from the bath house.

Another remarkable feature of this photo is the prominence of the Basilica on the skyline west of downtown. The Basilica was dedicated in 1914.

This is the view that Theodore Wirth hoped could one day be incorporated into the park system if the Minikahda Club ever relocated. Wirth wrote in the 1906 Annual Report of the Board of Park Commissioners, his first, that this view was of “such scenic beauty that it is almost a crime to pass it unnoticed.”

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Glenwood Spring: A Premier Park — and Water Supply?

H.W.S. Cleveland, the landscape architect who created the blueprint for Minneapolis’s park system in 1883, made his first visit to Glenwood Spring near Bassett’s Creek in north Minneapolis in the spring of 1888. In a letter to the Minneapolis Tribune, published April 22, 1888. Cleveland described that visit.

Bassett’s Creek in the vicinity of Glenwood Spring, about 1910 according to the Minnesota Historical Society. I’m not familiar enough with the lay of the land in the area to guess the exact location of this scene, but I was struck by how open the landscape was, especially given Horace Cleveland’s description of “large bodies of very fine native trees” in the vicinity of the spring. Perhaps those groves were behind the photographer. (Minnesota Historical Society)

Cleveland’s letter addressed the subject of the city’s water supply, noting that when he and his family moved to Minneapolis from Chicago in 1886 they experienced deleterious health effects — “winter cholera,” as he put it — that they thought might be associated with Minneapolis tap water. He reported that after they began using Glenwood spring water his family had no further health issues and they also found the spring water more “palatable” than the city water, which was taken from the Mississippi. Cleveland wrote that he had used the spring water for more than a year before he visited the neighborhood of the springs. When he finally did visit,

“I was not alone surprised and delighted by the beauty of the springs themselves, and their topographical surroundings, but amazed and grieved that my attention had not been called to the locality when I first came by invitation of the park commissioners, five years previous, to study the possibilities of park improvements.”

Cleveland claimed that because he was put in charge of an engineer, Frank Nutter, who, he was told, was familiar with all the sites desirable for park purposes, he didn’t feel it necessary to look at areas he was not shown. Cleveland didn’t believe he was deceived or misled, but…

“An hour’s inspection of the area in the neighborhood of these springs satisfied me that no place in the neighborhood of the city, except the vicinity of Minnehaha falls, was so well adapted by nature for the construction of a park, comprising rarely attractive topographical features — while the distance from the center of business was less than half that to Minnehaha, and the apparently unlimited capacity of the springs, which gushed from the hillsides at various points over a widely extended area, seemed to offer every possible opportunity for the ornamental use of water.”

The prospect of bubbling springs of clear water and “hills and valleys of graceful form” that wouldn’t have needed “heavy expense in grading” to be transformed into parkland appealed to Cleveland’s aesthetic sense. He also asked “whether it is worth our while to ascertain the character and capacity of the springs” to supply the entire city with water. Cleveland suggested that if the springs were capable of meeting the city’s water needs, “the city should secure them, and enough land around them to preserve them from contamination, and then enclose the area as an ornamental reservoir as had been done in Philadelphia, New York and Boston.

This photo of the ice house at Inglewood spring was taken in the mid-1890s. (Minnesota Historical Society)

What Cleveland didn’t know at the time was that the Glenwood and Inglewood springs may not have been well-known in 1883, when Nutter hosted Cleveland’s park exploration visit. Most accounts I can find of Glenwood Spring’s history claim it was discovered by William Fruen in 1884, a year after Cleveland wrote his “Suggestions for a System of Parks for the City of Minneapolis.” One account suggests Fruen found the springs in 1882. Some accounts have him discovering Glenwood Spring when building a mill on Bassett’s Creek, others when he was digging a fish pond. The latter tale, probably a tall one, was disseminated on the cached web site of the Glenwood Inglewood Water Company.

Fruen’s history with the spring includes filing the first vending machine patent in U. S. history. He invented a coin-operated machine in 1884 to dispense his spring water by the glass. Fruen also attempted to distribute his water by pipeline as Cleveland thought might be desirable. John West, owner of the posh West Hotel in Minneapolis, Thomas Lowry and Fruen wanted to build a two-mile pipeline from the spring to the West Hotel, and also sought permission to pipe the water into homes and restaurants along the way. That plan was vetoed in 1885 by Mayor George Pillsbury.

The Glenwood-Inglewood Company, 1910. The Glenwood and Inglewood springs were on adjacent property and run as separate water companies until about 1896. Until then, they were competitors. See below. (Minnesota Historical Society)

In the spring of 1885, Fruen published ads in the Tribune touting the purity of water from Glenwood Spring. He published a chemical analysis of the water conducted by Professor James Dodge of the University of Minnesota, who attested, “This water is extremely pure, being almost entirely free from organic matter.”

The ad invited readers to, “Drive out and see as fine a spring as you ever looked upon.” Another admonition in the copy is particularly interesting given the long association in later years of the Glenwood and Inglewood springs:

“Do not confound this spring with the Inglewood. Ours is the Glenwood.”

William Fruen’s son, Arthur, donated 13 acres of land along Bassett’s Creek to the park board in 1930, which was the beginning of Bassett’s Creek Valley Park. Arthur Fruen was a city council member at the time and an ex-officio member of the park board. I don’t know if that 13 acres included the site of the original spring—in other words, if Cleveland’s vision of a park that included the spring was partially realized nearly 50 years after he first saw it.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

An Early 8-hour Day?

Teamsters who worked for the Minneapolis Park Board began working 8-hour days in 1913. With only a quick look into the history of the eight-hour workday, that strikes me as a fairly early concession by the park board. Many industries still worked longer days. The park board Proceedings for 1913 reported that park commissioners adopted this proposal on May 6, 1913.

To the Honorable Board of Park Commissioners:

Your Standing Committee on Employment, to whom was referred the communication of the International Brotherhood of Team Owners asking that eight hours constitute a day’s work for teams employed by the Board, respectfully reports that the matter has been given careful consideration and your committee now recommends that all teams and men now employed by the Board working nine hours per day be placed upon a basis of an eight-hour day at the same wage per day now being paid.

Respectfully submitted,

J. W. Allan, W. F. Decker, P. D. Boutell, P. C. Deming

Nothing in park board proceedings indicates why employees were given what amounted to a 12.5% raise that year. Pay rates published in the February 18 proceedings list teamster pay at $2.50 per day and pay for teams at $5.00 per day. In other words, a driver was worth the same as a horse.

You have to keep in mind that a teamster in those days was usually someone who drove a “team” of horses—thus “teamster”—not a truck, in case you’ve ever wondered.

Work crews building what became Victory Memorial Drive in north Minneapolis in about 1920. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

The photo above, taken a few years after the reduction in work day was approved, shows that horses and automotive vehicles worked side-by-side on road construction.

Theodore Wirth wrote in 1911 that some projects had been delayed in Minneapolis parks because there were no teams to be hired. Perhaps the shorter workday was necessary to compete for teams in 1913.

I know that a widespread 40-hour work week didn’t come for many years in some places and some industries. Perhaps someone with a better knowledge of labor history than I can provide some context for the decision of the park board to reduce the work day from 9 to 8 hours, but maintain the same pay. Also is there any significance in the request for shorter work day coming from the brotherhood of “Team Owners,” which I gather was not the same as the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Any thoughts?

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Minneapolis Park Planning: Theodore Wirth as Landscape Architect. Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans, Volume I, 1906-1915

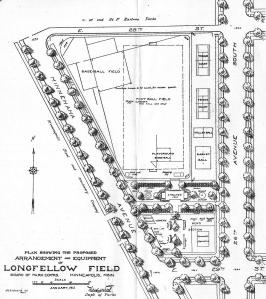

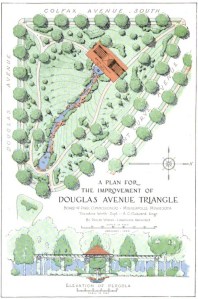

In Theodore Wirth’s 30 years as Minneapolis’s superintendent of parks (1906-1935), he produced annual reports that contained 328 maps, plans or designs for parks and park structures. Most of the plans were accompanied by some explanatory text, which provides a rich record of park board activity and Theodore Wirth’s priorities.

The annual reports include plans for recreation shelters, bridges, parkways, parks, playgrounds, gardens, golf courses, and more. Nearly every Minneapolis park is represented in some form, from if-cost-were-no-object conceptual designs for new parks to the “rearrangement” of existing parks. Many of the plans were never implemented due to cost or other objections; others were considerably modified after input from commissioners and the public.

In many cases over the years, Wirth referred in his written narratives to plans published in prior years that he hoped the board would implement. Sometimes it did, often it didn’t. One of the drawbacks to implementing Wirth’s plans was the method of financing park acquisitions and improvements during much of his tenure as superintendent. The costs of both were often assessed on “benefitted” property, along with real estate tax bills. In other words, the people who lived near a park and received the “benefit” of it—both in enjoyment and increased property values—had to pay the cost, usually through assessments spread over ten years. To be able to assess those costs, however, a majority of property owners had to agree to the assessment, and in many neighborhoods property owners refused to agree until plans were modified considerably to reduce costs.

Phelps Wyman’s plan for what is now Thomas Lowry Park from the 1922 annual report is one of the only colored plans and one of the only plans that wasn’t produced by the park board staff.

Many of the annual report drawings contain a “Designed by” tag, but many do not have any attribution. For those that don’t, it is sometimes unclear who the actual designer was. In many cases it would have been Wirth, but in some cases—the golf courses are notable examples—others would have been responsible for the layouts even though they weren’t credited. William Clark, for instance, is known to have designed the first Minneapolis golf courses, Wirth said so, but only Wirth’s name appears on these plans, not Clark’s.

Also, because these plans were created while Wirth was superintendent does not mean that the idea for each project originated with Wirth. Some of the demands for the parks featured here pre-dated Wirth’s arrival in Minneapolis by decades. Other plans were largely his creation. In most cases, however, Wirth was responsible for implementing those plans.

The majority of the drawings were reproduced on a thin, tissue-like paper that could be folded small enough to be glued into the annual reports. The intent was to publish plans large enough to be readable, but not too bulky. The paper is fragile and easily torn when unfolding; I doubt that many of the plans survive. Even where efforts have been made to preserve and digitize the annual reports, such as by Hathitrust and Google Books, the plans on the translucent sheets are not reproduced. In many cases it would require a large-format scanner to digitize them from the annual reports. Originals do not exist for most of these plans, because they were not working plans.

Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans

I’ve been threatening for some time to do something that probably only the planners at the Minneapolis park board and a few others will appreciate. I’m publishing a complete list of the park plans that appeared in the annual reports of the park board. I’m periodically asked when a certain park was discussed, acquired or planned and I search my list of annual report plans quickly to provide some direction. I hope that by publishing this catalog of park plans I can save other researchers a great deal of time.

Unfortunately I do not have copies or scans of the plans themselves. Neither does the park board. You’ll have to go to the Central Library in downtown Minneapolis to view the original annual reports and see these plans. The Gale Library at the Minnesota Historical Society also has copies of the park board’s annual reports for many years.

I’ve started this catalog with the 1906 annual report, the first year that Theodore Wirth was responsible for producing the report, his first year as superintendent of Minneapolis parks. (Several of H.W.S. Cleveland’s original park designs were reproduced in earlier annual reports. I’ll provide a list of those in the very near future. You may still view the very large originals of many of Cleveland’s plans, by appointment, at the Hennepin History Museum. It’s worth a visit!)

The annual reports of the park board were divided into several parts: a report by the president of the park board, reports by the superintendent and attorney, financial reports, and an inventory of park properties. Most of the plans described here were a part of the superintendent’s report. For that reason, I’ve cited the date on Wirth’s reports rather than the date of the president’s report, which at times differed.

I will post the catalog of plans, maps and drawings in three “volumes” due to the size of the file—more than 9,000 words in total. Go to the Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans 1906-1915

Mystery Starters at Powderhorn Speed Skating Track

This photo is labelled “Olympic Speed Skating Team.” The only date on it is February 16, 1947. That seems too early to have already selected skaters for the 1948 Olympic team. Can anyone identify the skaters? Local skaters Johnny Werket and Ken Bartholomew represented the U.S. at the 1948 Olympics in St. Moritz and Bartholomew won a silver medal. Gene Sandvig and Pat McNamara represented Minneapolis and the U.S. at the 1952 and 1956 Winter Games. (I posted more about those skaters here.) They might all be in this photo.

Can you identify any of these people — skaters and others — at the speed skating track at Powderhorn Park? (MPRB) (Note 9/18: Reader Tom McGrath has identified the starter and the skaters in a comment below. Thanks, Tom and Brian.)

I don’t know the skaters, but I do recognize the fellow in the dark overcoat next to the starter. Anybody know who that is — and what his job was at the time?

I don’t know the guy with the starter’s pistol, but he looks entirely too jolly to be a regular race official. Seems more like a politician holding a noisemaker, but I can’t name him.

Name them all and you get a free lifetime subscription to minneapolisparkhistory.com. (That’s the lifetime of the website, not you.) Be the first to name the man in the dark coat and I’ll email you a free, low-quality photocopy of Gen. John “Blackjack” Pershing’s letter to the Minneapolis park board in 1923 expressing his appreciation for having a park named for him. (More on that story later.)

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Sibley Field Flattened 1923

Sibley Field was one of the bigger challenges the park board faced when it came to building neighborhood recreation parks. 1923 was a very busy year as the park board developed Sibley Field, Chicago Avenue (Phelps) Field and Nicollet (MLK) Field in south Minneapolis, Folwell Field and Sumner Field in north Minneapolis and Linden Hills Field in southwest. But Sibley may have been the biggest challenge, because all four corners of the park were at different grades. Park superintendent Theodore Wirth wrote afterwards that Sibley was one of the only projects for which costs had been seriously underestimated due to the expense of moving dirt. To create level fields, park board crews used a steam shovel and horse teams to move 68,000 cubic yards of earth.

This is one of my favorite photos of neighborhood park construction. It shows dramatically how much earth had to be moved to create an expanse of level ground suitable for playing fields. I wonder if the home owners who sat near the precipice on 20th Avenue South were ever worried.

As I noted in my profile of Sibley Field on the park board’s website, Wirth wrote in the park board’s 1923 annual report that the “formerly unsightly low land” was brought to an “attractive and serviceable” grade.

Photos like this reinforce my admiration for all the people — from neighborhood residents to city leaders — who envisioned, supported, planned and paid for the parks that have made life in Minneapolis better for many generations.

David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: The Complete List, Part III

This is the third and final installment in a series on “Lost Parks” in Minneapolis. (If you missed them, here are Part I and Part II.) These are park properties that once existed, but did not survive as parks. There is a quiz question at the end of this article. It’s very hard.

St. Anthony Parkway (partial). In 1931, the park board swapped the recently completed portion of St. Anthony Parkway from the southern tip of Gross Golf Course to East Hennepin Avenue for the land on which Ridgway Parkway was built from the golf course to Stinson Parkway. The park board gained 19 acres of land in the deal and the entire cost of constructing Ridgway Parkway was also paid. This story of the parkway “diversion” will be told in greater detail some day. It was controversial. (Read the broad outlines of the diversion of St. Anthony Parkway.) Some people have claimed that the diversion of St. Anthony Parkway is one reason for the “Missing Link” in the Grand Rounds. But that link had gone missing long before the “diversion” and wouldn’t have been found with or without the diversion.

Sheridan Field. University Avenue NE and Twelfth Avenue NE, 1.25 acres. The park board purchased the half-block of land across the street from Sheridan School for $7,000 in 1912. At the park board’s request, Twelfth Avenue was vacated between the school and park. The new playground was provided with a backstop for a baseball field and a warming house for ice-skating, but few other improvements were made. In the early 1920s park superintendent Theodore Wirth urged the park board to either expand the playground or abandon it. He believed the site was too small. It was “inadequate,” he wrote, to provide for the “large attendance (it) constantly attracts.” In the 1924 annual report Wirth presented a plan for the enlargement and development of the park, but that was the last mention of the possibility of expanding the playground. A new, much larger Sheridan School was built on the site in 1932, and the following year the park board granted the school board permission to use the park as a playground for the school, provided that all maintenance and improvements would be the responsibility of the school board. It wasn’t until 1953 that the park board officially abandoned the site. In a land swap with the school board, the park board gave up the under-sized Sheridan Park for the site of the former Trudeau School at Ninth Avenue SE and Fourth Street SE. The park at the Trudeau site became Elwell Field II.

Small Triangle. Royalston Avenue in Oak Lake Addition, 0.01 acre. The triangle was never officially named; it was called “small” because it was. Very small. (See Oak Lake.)

John Pillsbury Snyder and Nelle Stevenson Snyder the day they reached New York after being rescued from the Titanic. (StarTribune and Phillip Weiss Auctions)

Snyder Triangle. Fifth Avenue South and Grant Street, 0.06 acre. Purchased by resolution January 15, 1916 for $4,578. The park board had considered and rejected buying the triangle in 1886. The park was named for Simon P. Snyder, a real estate agent who once owned much of the land in the area. As Patrick Dea pointed out in a comment several months ago, Simon Snyder’s grandson, John Pillsbury Snyder, was a 24-year-old first-class passenger on the maiden voyage of the Titanic in 1912. He and his bride, Nelle Stevenson, were returning from their honeymoon — and survived. The triangle named for his grandfather did not. It was lost to freeway construction for I-35W. A triangle park exists today very near the old location, but it’s not owned by the park board. In 1967 the park board offered to help the state highway department landscape the new triangle between I-35W entrance and exit ramps and 10th Street. The old Snyder Triangle appears to be partly under the Grant Park building on Grant Street. I have not found a record of the price the little triangle fetched.

Stevens Circle. Portland Avenue and 6th Avenue South, 0.06 acre. The small park was named for Col. John Stevens in 1893, but at that time it was named Stevens Place. The name was changed to Stevens Circle on August 1, 1928. From its acquisition in 1885 to 1893 the property was called Portland Avenue Triangle. It is not known if a change in the shape of the park prompted the name change from triangle to place to circle. The park was transferred to the park board from the city council in 1885 according to park inventory lists, although there is no record of the transfer in park board proceedings. The only indication of park board ownership of the triangle was an entry in the expenditures of the park board for 1885 for “Triangle, Portland Avenue and Grant Street” in the amount of $1.50. The triangle became the home of a statue of Col. Stevens in 1911. The circle was given back to the city for traffic purposes in 1935, at which time the statue of Col. Stevens was moved to Minnehaha Park and placed near the Stevens House.

Stinson Boulevard (partial). From East Hennepin to Highway 8. 24 acres. A section of the boulevard was given to the city in 1962 because functionally it was a business thoroughfare, not a parkway. The section given to the city included all of the original land donated for a boulevard by James Stinson et al in 1885. It’s good we still have some Stinson Parkway remaining, because as I explained in the history of Stinson Parkway on the park board’s website, I think Stinson Parkway helped keep alive the plans of Horace Cleveland for a parkway that encircled the city. Without Stinson’s generosity, we might not have the Grand Rounds today.

Svea Triangle. Riverside Avenue and South 8th Street, 0.09 acre. The first mention of the triangle is in the minutes of the park board’s meeting of May 3, 1890 when the board received a request that it improve the triangle. The problem was that the park board didn’t own it. So, on June 27, 1890 the city council voted to turn over the triangle to the park board. The land had been donated to the city in 1883 by Thomas Lowry and William McNair and their wives for park purposes. The triangle was reportedly named on December 27, 1893 to honor Swedish immigrants who had settled in the neighborhood. It had previously been known simply as Riverside Avenue Triangle. The triangle was traded to the city council in 2011 in exchange for a permanent easement between Xerxes Avenue North and the shore of Ryan Lake in the northwestern corner of Minneapolis. The city council requested the exchange when making improvements to Riverside Avenue. Svea Triangle is the most recent park lost.

Vineland Triangle. Vineland Place and Bryant Avenue South, 0.05 acre. Transferred to the park board from the city council, May 10, 1912. The triangle was paved over in a reconfiguration of the street past the Guthrie and Walker entrances in 1973, but remains on the park board’s inventory.

Virginia Triangle. Hennepin, Lyndale and Groveland avenues, 0.167 acre. The triangle was apparently named for the Virginia Apartments adjacent to the triangle. The triangle was traded to the park board by A. W. French and wife on January 1, 1900 in exchange for a piece of land they had originally donated for a parkway along Hennepin Avenue. The triangle was sold in 1966 to the Minnesota Highway Department to accommodate interchanges for I-94. The price tag was $24,300, plus the cost of relocating the Thomas Lowry Monument, which had stood on the triangle since 1915. Read much more about Virginia Triangle and the monument here.

Walton Triangle. No property by this name was ever listed in the park board inventory or Schedule of Parks, but was included in the 1915-1916 proceedings in a schedule of wages for park keepers. Walton Triangle was included with Virginia Triangle, Douglas Triangle and Lowry Triangle and other properties in that neighborhood as the responsibility of one parkkeeper. This mysterious property likely got its name from Edmund Walton, a well-known realtor and developer, who lived on Mount Curve Avenue near where this property must have been located.

This photo from the Brady-Handy Collection at the Library of Congress is almost certainly Eugene Wilson when he was a Congressman from Minnesota 1869-1871. The photo by Matthew Brady is identified only as Hon. [E or M] Wilson, but resembles very closely other images of Wilson.

Other Losses to Freeways and Highways.

In addition to the parks listed above, the following Minneapolis parks were trimmed by construction of freeways:

- I-94: Luxton, Riverside, Murphy Square, Franklin Steele Square, The Parade, Perkins Hill, and North Mississippi, as well as easements for bridges over East and West River Parkway.

- I-35W: Dr. Martin Luther King, Ridgway Parkway, Francis Gross Golf Course. The highway department also acquired an easement from the park board to build a bridge over Minnehaha Creek.

- I-394: Theodore Wirth Park, Bryn Mawr, The Parade

- Hwy 55: Longfellow Gardens

I’ve only included properties that were officially acquired or improved, then later disposed of for some reason. The informal parks and playgrounds in empty lots that existed in many neighborhoods, but were never owned or improved by the park board, are not included. I’ve also left out small pieces of a few parks that were sold for various reasons over the years, other than those taken for highways.

If you can add to or correct this list, please let me know. Do you remember anything about any of these former parks? If you do, please send me a note so we can preserve something of them.

TRIVIA TEST. Here’s the Ph.D.-level park quiz question inspired by one of these entries. Two people had two completely different stretches of parkway named for them. One of those people was St. Anthony. (You could argue the parkways were named for the town, not the man, but this is my quiz.) The first parkway named for St. Anthony is now officially East River Parkway. Later the name was given to the parkway across northeast Minneapolis. Name the other person who had two different parkways named for him. Only one of them still has his name.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Keewaydin Park Before and After — 1928

Like a lot of other people I’m curious to see the new look of Keewaydin Park and School. Construction is underway. It has to be an improvement over what was there a few years ago.

Okay, it was a long time ago. In 1928-29 the park board hauled in 38,600 cubic yards of fill to bring the playing fields up to grade on one side. Clearly the neighbors tried to help by discarding their refuse there, too. The crate says “Morell’s Pride Hams and Bacon.” But that wasn’t enough; the fill kept settling. The park board continued to fill the former swamp in 1930-31. By 1932 the field had been filled sufficiently to be regraded and have tennis courts and a wading pool finished. By 1934 the grounds looked much nicer.

Keewaydin was one of the early collaborative projects between the park and school boards. In the park board’s 1929 annual report it noted that the park had one of the best-equipped shelters for skating and hockey rinks due to the “well-appointed” basement rooms of the school. The doors on the lower level in this photo must have been the entrance to those rooms.

Anybody remember skating there or going to school there when it was new? Does anybody want to take a photo of present construction and email it to me? I forgot to zip over and take one Sunday when I was at Longfellow House.

David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: The Complete List, Part II

This is Part II — H-R — of an alphabetical list of “lost” Minneapolis parks. These are park properties that were officially acquired or improved by the park board, but then were sold or given away. (If you missed Part I — A-G — click here.)

Hennepin Avenue South. 17.5 acres. The main parkway link from the city — Loring Park — to Lake Harriet was supposed to be Hennepin Avenue. The park board spent considerable effort and money to establish Hennepin Avenue as a parkway, beginning in 1884, but it was too heavily used as a commercial route and thoroughfare to be the beautiful and tranquil parkway the park board desired. Instead, Charles Loring created a route to Lake Harriet out Kenwood Parkway, then around Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun, an integral part of what would become the Grand Rounds. The park board returned ownership of Hennepin Avenue South, from Lyndale to Lake Street, to the city in 1905. I’ll write more of the Hennepin Parkway story eventually.

Hiawatha Triangle. Minnehaha Avenue and East 32nd Street, 0.5 acre. Purchased September 6, 1910 for $2,975. In 1960, the City Planning Commission informed the park board that the triangle was to be rezoned, probably as residential. I don’t know if that played a role in the subsequent sale of the property. On September 7, 1960 the park board accepted bids on several parcels of land, including an oral bid by Lawrence Hauge of $35,500 for Hiawatha Triangle, or Lots 1-4 of Block 7, Rollins Addition. Hauge’s bid was accepted. He purchased the land for what became McDivitt-Hauge Funeral Home.

Highland Oval. Highland Avenue in Oak Lake Addition, 0.058 acre. (See Oak Lake.)

Hillside Triangle. Hillside Avenue and Logan Avenue North, 0.6 acre. Transferred from the city council September 20, 1892. The park board granted a request from the school board to use the triangle as a playground for Lowell School in 1921. Title for the land was transferred to the school board in 1953. Lowell School closed in 1974. Houses were built on the former triangle and school site.

Iagoo Triangle. Hiawatha Avenue and East 45th Street, 0.05 acres. Donated to the park board by William Adams and wife, March 17, 1886, along with Osseo Triangle. The triangle was named for the story-teller in Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha. Sold to the Minnesota highway department in 1966 for the proposed Highway 55 freeway. The purchase price is not contained in park board records.

Kenwood Triangle. Penn Avenue South, Oliver Avenue South and West Franklin Avenue, 0.02 acre. Transferred from the city council to the park board June 3, 1907 when Kenwood Park was acquired. This is another triangle still on park board books, but listed as “paved.” The traffic intersection was altered in 1981, when the park board and school board collaborated on the construction of the recreation center attached to Kenwood School.

Lakeside Oval. Lakeside Avenue in Oak Lake Addition, 0.32 acre. (See Oak Lake.)

LaSalle Triangle. LaSalle Avenue and 13th Street South, 0.05 acre. Transferred to the park board from the city council June 7, 1922. The triangle was returned to the city in 1976 as a part of street reconfiguration.

Longfellow Field I. Minnehaha Avenue and East 26th Street, 4 acres. Purchased in 1911 for about $7,000. Sold in 1917 for $35,000. That’s only the beginning of the story. Read the rest and see more photos here.

The playground at the first, “lost” Longfellow Field in 1912. (Minneapolis Collection, Hennepin County Library)

Lowry Triangle. Hennepin, Lyndale and Vineland Place, 0.16 acre. Transferred from the city council November 28, 1891. Lost to I-94 in 1964. See much more detail here. The highway department’s initial offer of $1,500 for the triangle was rejected by the park board and the board instructed its attorney to oppose that valuation in court. By September 1967 the offer for the triangle had increased to $5,000 and the park board still wasn’t biting. Park board proceedings and annual reports never reported the final sale price of the property. Someday I’ll look through Hennepin County records to see what I can find.

Lyndale Avenue North. 16.65 acres. Lyndale Avenue North was intended to be the primary parkway into North Minneapolis in what later became known as the Grand Rounds. It was too much a commercial avenue ever to serve the purpose of a parkway connecting Loring Park to Farview Park, however. After twenty years of trying to make it a parkway between Western (Glenwood) Avenue and 29th Avenue North, the park board gave up and turned it over to the city to maintain as an ordinary street in 1905. The park board abandoned Hennepin Avenue South at the same time.

Lyndale Farmstead (partial). The half-block south of West 40th Street between King’s Highway and Colfax Avenue, 1.78 acres. Acquired from James J. Hill and Thomas Lowry in 1909 as part of the land donated for a superintendent’s house. Theodore Wirth recommended selling the land in the 1912 Annual Report and using the proceeds to build a laundry at the Lyndale Farmstead shops for washing the napkins and table cloths from park refectories, and towels and swimming suits from the bath houses. Other uses were later proposed for revenue from the sale of the 14 lots platted there. In 1922 the board decided to sell the lots, asserting that no park use was ever intended for that land. All of the lots were sold by 1925. Annual report figures for those years only show revenue of $17,155 from land sales, but that likely understates total revenue as the lowest listed sale price I can find for any single lot was $1,750. All revenues from sales went into a fund for the operation and improvement of Lyndale Farmstead. Curiously, in the midst of the sale of those lots, Wirth published a plan for the improvement of Lyndale Farmstead in the 1924 Annual Report that included building four tennis courts at the corner of King’s Highway and West 40th St.

Market Square. Main Street and today’s Central Avenue. Transferred to the park board April 27, 1883. The city council had acquired the land in exchange for the assistance it had provided in constructing a dam to protect St. Anthony Falls. On January 22, 1886 the city council voted to cede the land to the Minnesota Industrial Exposition as part of the ground to be used for an Industrial Exposition Building.

Midway Triangle. University Avenue and Bedford Street SE, 0.03 acre. Acquired from the city council, October 1, 1919. The park board noted at its meeting November 1, 1944 that the triangle had already been paved over as part of the widening of University Avenue and, therefore, transferred title back to the city council. See more detail on this and other Prospect Park triangles here.

Mississippi Park. Land was lost on both sides of the Mississippi River when the Meeker Island Dam and later the Ford Dam were built. The park board also lost several islands in the river, including Meeker Island, which were submerged in the reservoirs behind the dams. The story of the construction of the dams and their impact on Minneapolis parks deserves more detail than I can give it here. The west side of the river gorge from Franklin Avenue to Minnehaha Park should be named for Horace William Shaler Cleveland, the man who did so much to ensure that the river banks became a park.

Oak Lake. Lakeside and Border avenues in Oak Lake Addition, 1.33 acres. Oak Lake and other parks in the Oak Lake Addition — Highland Oval, Lakeside Oval, Royalston Triangle and Small Triangle — were donated as parks in the original plat of Oak Lake Addition by Samuel C. Gale et al., October 22, 1873. The Farmers’ Market on Lyndale sits on what was once the first Minneapolis lake to become a park. (The story of the little lake and Oak Lake Addition is fascinating. I’ll re-post it someday soon.)

Oak Street Triangle. Officially part of East River Parkway at Oak Street, but known as Oak Street Triangle. Sold to U of M in 1961 for a price that is not recorded in park board records.

Osseo Triangle. Hiawatha Avenue and East 46th Street, 0.03 acres. Donated by William Adams and wife, March 17, 1886 along with Iagoo Triangle. In keeping with the Longfellow theme in the neighborhood named for him, the triangle was named for another character in The Song of Hiawatha; Osseo was the Son of the Evening Star. Sold to Minnesota Highway Department for Highway 55 freeway in 1966 for an unknown price.

The dedication of Pioneers Square in front of the post office was held November 13, 1936 to honor, Charles M. Loring, the “Father of Minneapolis Parks.” It would have been his 103rd birthday.(Minnesota Historical Society)

Pioneers Square. Marquette Avenue and Second Street South, across from the post office, 2.5 acres. The land was purchased and developed by the park board at the request of the city council. The U. S. Postal Service wanted to construct a new post office in downtown Minneapolis, but insisted that it be set in attractive environs, a park. The park board rejected the plan of the city council to assess the nearly half-million dollar cost of acquisition, demolition and improvement mostly on the surrounding property owners at the onset of the Great Depression in 1930. The park board finally agreed to the deal in 1932 when the city council authorized $320,000 in bonds to cover about 80 percent of the cost of the land. The remaining costs were assessed on property owners.

The new post office and Pioneers Square — and The Gateway, a couple blocks west — did not lead to urban renewal in the area. (With the snow melt at the end of the winter of 1953, maintenance crews picked up 70 bushel baskets of empty wine and whiskey bottles from The Gateway. One Monday morning in the summer of 1953, crews picked up 62 empty wine and whiskey bottles from the grass at Pioneers Square. [Charles E. Doell Papers, Hennepin History Library]) The city condemned Pioneers Square and The Gateway in 1960 in a new round of urban renewal. The Pioneers Monument was moved to a small triangle in northeast Minneapolis in 1967, which the city sold to the park board for a dollar. The statue was moved across Marshall Avenue to the B. F. Nelson park site in 2011.

Rauen Triangle. Eleventh Avenue North and Fifth Street, 0.027 acre. Purchased in 1890. Turned over to the city in 1939. (See more of the story and photos here.)

Royalston Triangle. Royalston Avenue and 6th Avenue North in Oak Lake Addition, 0.20 acre. (See Oak Lake.)

I’ll post Lost Minneapolis Parks: The Complete List, Part III soon.

Do you remember anything about any of these former parks? If you do, send me a note so we can preserve some recollection of them.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: The Complete List, Part I

I’ve written about several parks in Minneapolis that are no more. Since then I’ve been asked if there is a list of those “lost” parks. The short answer is, “Not until now.” Here’s the first part of an alphabetical list I’ve compiled from park board proceedings and annual reports.

19th Avenue South and South 1st Street. 1.0 acre. The park board’s 1948 annual report noted that the site near Seven Corners had been graded and frames had been installed for swings, teeter-totters and slides for small children. The plan was to complete the playground in 1949. This parcel was leased specifically for use as a playground. I don’t know the terms of the lease, but it was still included in park inventory as leased land in the 1964 annual report. The U of M’s West Bank softball fields are now near the site. 19th Avenue South at that point is the approach to the 10th Avenue Bridge over the Mississippi River.

Bassett Triangle. 7th Avenue North and 7th Street North, 0.03 acre. Acquired from the city council December 3, 1924. Returned to the city council in 1968, after the board hired appraisers in 1967 to try to sell the property. The site is now occupied by a Wells Fargo Bank. The property was named for Joel Bean Bassett, who owned much of the land in the vicinity in the 1800s. Bassett’s Creek, underground not far away, is also named for him.

Bedford Triangle. Orlin Avenue SE and Bedford Avenue SE, 0.01 acre. This little triangle in Prospect Park was still carried on the park board’s inventory the last time I checked, but it was listed as “paved.” There is no visual evidence of the triangle. Read more about this and other triangles in the meandering streets below Tower Hill.

Brownie Lake (partial). Theodore Wirth Park west of Brownie Lake and south of Highway 12, 32 acres. The land was sold in 1952 to the Prudential Insurance Company for $200,000 and some additional land.

The southern end of Theodore Wirth Park west of Brownie Lake got a makeover when the Prudential Insurance Company purchased the land for its regional headquarters in 1952. It was the largest section of park land the Minneapolis park board has ever sold. Construction is underway in this 1954 photo. (Minneapolis Star Journal Tribune, Minnesota Historical Society)

The park board bowed to intense public pressure to sell the land beside the lake. Prudential had made it clear that the site adjacent to the lake was the only site it would consider for its offices in the city. Ultimately the park board was convinced that the benefit to the Minneapolis economy was a greater good than keeping the land as a park. The board justified its action in part by asserting that with the growth of traffic on Highway 12 (now I-394) and the widening of that road, the land west of Brownie Lake had already been isolated from the rest of Wirth Park anyway.

Cedar Avenue Triangle. Cedar Avenue and 7th Street South, 0.02 acre. The triangle was offered to the park board by Edmund Eichorn on April 15, 1891. After delaying a decision for a couple of months, the board agreed to pay Eichhorn $2,394 over ten years without interest. The triangle, adjacent to what is now the Cedar Avenue exit ramp from I-94 westbound, was sold to the state highway department in 1965 for $1,000. In April of that year the board approved a resolution to sell the property for $1,000 plus “other valuable considerations.” Later that year the board approved dropping the “other valuable considerations” clause.

Crystal Lake Triangle. West Broadway and 30th Avenue North, 0.05 acre. The triangle was supposedly purchased July 21, 1910 and sold to the state in 1962 for $2,700. It once sat at the edge of what is now the hideous intersection of Theodore Wirth Parkway, West Broadway (County Highway 81) and Lowry Avenue. Imagine if Phelps Wyman’s 1921 plan for that complex intersection had been used. What a difference it would have made in that part of Minneapolis. It would’ve been gorgeous.

Dell Place. Dell Place between Summit and Groveland avenues, 0.04 acre. Transferred from the city council April 27, 1883 when the park board was created. Citizens near the tiny lot petitioned the park board in 1907 to plant and maintain the grounds, which the park board agreed to do — if residents of the area would first pay to have the parcel curbed and filled to street grade. The street triangle was sold to the Minnesota highway department for I-94 interchanges in 1964 for $1,350. The park board had rejected the state’s first offer of $450. The park board’s appraisers valued the land at $2,250, but the park board accepted an internmediate figure instead of proceding to court with litigation.

Elwell Field I. East Hennepin and 5th Avenue SE, 3.7 acres. Purchased in 1939 from the Minneapolis Furniture Company for $5,000. Sold to Butler Manufacturing in 1952 for $55,000. The somewhat isolated field, surrounded by industrial buildings, was sold with the promise to the neighborhood to acquire another playground nearer Holmes School. Eventually the land adjacent to the school was purchased as a playground. The school on the former Holmes site, built in 1992, is now named Marcy Open School.

The first Elwell Field, 1952. Across the field is a building of the Butler Manufacturing company, which purchased the field the year the picture was taken. (Norton and Peel, Minnesota Historical Society)

Elwell Field II. 9th Avenue SE between SE 4th Street and SE 5th Street, 1 acre. The former site of Trudeau School was acquired February 4, 1953 in a trade with the school board. The park board gave up Sheridan Field next to Sheridan School at Broadway and University Avenue NE for the Trudeau property. The second Elwell Field was condemned by the state highway department for I-35W in 1962. The park board accepted a negotiated payment of $125,000 for the park in 1966.

Franklin Triangle. Franklin Terrace and 30th Avenue South, 0.05 acre. Transferred to the park board from the city council August 13, 1915 and accepted and named by the park board September 6, 1916. Taken by the state highway department for I-94 in 1962 in exchange for $1 and “other valuable considerations” again.

The beautiful cover of the park board’s 1915 annual report depicted the fountain at The Gateway. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

The Gateway. Hennepin and Nicollet avenues, 1.22 acres. There is still a Gateway park property at Hennepin and 1st Street South, but it’s not in the same location, so I consider this original Gateway a lost park. I have already provided the outline of the story for the original Gateway on the history pages of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board’s website at minneapolisparks.org.

Groveland Triangle. Groveland and Forest avenues, 0.21 acre. The triangle was purchased in November 1910 for $8,979. It was sold to the state highway department for the construction of I-94 in 1964 for $8,900.

That’s all for Part I of Lost Minneapolis Parks. Part II — H-R — will be out soon.

Historical profiles of all existing Minneapolis parks can be found at the website of the Minneapolis park board. Each park has its own page with a “History” tab.

If you remember anything about any of the lost parks mentioned here, please send me a note so we can preserve something of those parks — especially the property beside Brownie Lake. Any memories before Prudential moved in?

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Leave a comment

Leave a comment