Archive for the ‘Winter Sports’ Category

Elusive Minneapolis Ski Jumps: Keegan’s Lake, Mount Pilgrim and Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park

The Norwegians of Minneapolis had greater success getting their music recognized in a Minneapolis park than they did their sport. A statue of violinist and composer Ole Bull was erected in Loring Park in 1897.

This statue of Norwegian violinist and composer Ole Bull was placed in Loring Park in 1897, shown here about 1900 (Minnesota Historical Society)

A ski jump was located in a Minneapolis park only when the park board expanded Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park in 1909 by buying the land on which a ski jump had already been built by a private skiing club. The photo and caption below are as they appear in the annual report of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners for 1911.* While the park board included these photos in its annual report, they are a bit misleading. Park board records indicate that it didn’t really begin to support skiing in parks until 1920 — 35 years after the first ski clubs were created in the city.

Minneapolis, the American city with the largest population of Scandinavians, was not a leader in adopting or promoting the ski running and ski jumping that originated in that part of the world. Skiing had been around for millenia, but it had been transformed into sport only in the mid-1800s, around the time Minneapolis was founded. Ski competitions then included only cross-country skiing, often called ski running, and ski jumping — the Nordic combined of today’s Winter Olympics. Alpine or downhill skiing didn’t become a sport until the 1900s. Even the first Winter Olympics at Chamonix, France in 1924 included only Nordic events and — duh! — Norway won 11 of 12 gold medals.

The first mention of skiing in Minneapolis I can find is a brief article in the Minneapolis Tribune of February 4, 1886 about a Minneapolis Ski Club, which, the paper claimed, had been organized by “Christian Ilstrup two years ago.” That article said the club “is still flourishing.” Eight days later the Tribune noted that the Scandinavian Turn and Ski Club was holding its final meeting of the year. The two clubs may have been the same.

Ilstrup was one of the organizers two years later of one of the first skiing competitions recorded in Minneapolis, which was described by the Tribune, January 29, 1888, in glowing and self-congratulatory terms.

Tomorrow will witness the greatest ski contest that ever took place in this country. For several years our Norwegian cultivators of the noble ski-sport have worked assiduously to introduce their favorite sport in this country, but their efforts although crowned with success, did not experience a real boom until the Tribune interested itself in the matter and gave the boys a lift.

The Tribune mentioned the participation in the competition of the Norwegian Turn and Ski Club, “Vikings club” and “Der Norske Twin Forening.” The Tribune estimated that 3,000 spectators watched the competition held on the back of Kenwood Hill facing the St. Louis Railroad yard. Every tree had a dozen or so men and boys clinging to the branches, while others found that perches on freight cars in the rail yard provided the best vantage point.

The caption for this photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Visual Resource Database claims the photo is from the winter of 1887, but was almost certainly taken at the ski tournament held on Kenwood Hill late that winter in February, 1888.

The competition consisted of skiers taking turns speeding downhill and soaring off a jump or “bump” made of snow on the hill. Points were awarded for distance and for style points from judges.

The winners of the competition were reported as M. Himmelsvedt, St. Croix Falls, whose best jump was 72 feet, and 14-year-old crowd favorite Oscar Arntson, Red Wing, who didn’t jump nearly as far, but jumped three times without falling. Red Wing was a hot bed of ski-jumping, along with Duluth and towns on the Iron Range. (The winner was perhaps Mikkjel Hemmestveit, who along with his brother, Torger, came from Norway to manufacture skis using highly desirable U.S. hickory. The Hemmestveit brothers are usually associated with Red Wing skiing, however, not St. Croix Falls.)

A Rocky Start

Despite the enthusiasm of the Tribune and the crowds, skiing then disappeared from the pages of the Tribune until 1891, when on March 2, the paper reported on a gathering of thirty members of the Minneapolis Ski Club at Prospect (Farview) Park. “This form of amusement is as distinctively Scandinavian as lutefisk, groet, kringles and shingle bread,” the Tribune reported. “With skis on his feet a man can skim swiftly over the soft snow in level places, and when a slope is convenient the sport resembles coasting in a wildly exhilarating and exciting form,” the report continued. The article also described the practice of building snow jumps on the hill, noting that “one or two of the contestants were skilful enough to retain their equilibrium on reaching terra firma again, and slid on to the end of the course, arousing the wildest enthusiasm.”

The enthusiasm didn’t last once again. The Tribune’s next coverage of skiing appeared nearly eight years later — but it came with an explanation:

During recent winters snow has been a rather scarce article. A few flakes, now and then, have made strenuous efforts to organize a storm, but generally the effort has proven a failure. The heavy snow of yesterday was so unusual that it is hardly to be wondered at that there arose in the breasts of local descendants of the Viking race a longing for the old national pastime, skiing…The sport of skiing was fostered to a considerable extent in the Northwest, and particularly in this city, a few years ago, but the snow famine of late winters put a damper on it.

— Minneapolis Tribune, November 11, 1898

The paper further reported that the “storm of yesterday had a revivifying effect upon the number of enthusiasts” and that the persistent Christian Ilstrup of the Minneapolis Ski Club was arranging a skiing outing on the hills near the “Washburn home” (presumably the orphanage at 50th and Nicollet). The paper also reported that while promoters of the club were Norwegian-Americans, “they do not propose to be clannish in the matter.”

Within a week of that first friendly ski, Continue reading

This is why we love our parks: Powderhorn Art Sled Rally

Creative use of space. It is the true gift of parks. If anyone ever needed convincing of the incredible benefits of public spaces, they should have been at Powderhorn Park yesterday for the 4th Annual Art Sled Rally. Thrills, chills and plenty of spills. Marvelous creativity. Wacky fun. It’s what a creative community can do when it has a place to do it.

Cheers to South Sixteenth Hijinks for the idea and energy. Be sure to click the link above to learn more about the event and organizers. Especially check out the sponsors and please support them.

I didn’t see all the sleds, but among my favorites were the bear from Puppet Farm, (picture a bear sliding on its stomach, and, yes, there was a child seated on top of the bear sled, too) and a wild dinner table on a sled, which I believe was called “Dinner at the Carlisle’s.” Other favorites were a couple of dragons, a dragon fly, a bunch of eyeballs and a London Bridge, which did indeed fall down. Some pictures are already posted on artsledrally.com from Dan Stedman. I hope others will soon follow.

The greatest tribute to the event and the people who made it happen: as we walked away my daughter asked, “Can we make a sled next year?”

David C. Smith

Powderhorn Park Speed Skating Track: Best Ice in the United States

Many years before Frank Zamboni invented his ice resurfacer (in California!?), Minneapolis park board personnel had to prepare the speed skating track at Powderhorn Park mostly by hand for international competition and Olympic trials. They were very good at it.

Olympic medalist speed skater Leo Friesinger from Chicago (whom you already met in these pages here) had this to say after he won the Governor Stassen trophy as the 10,000 Lakes senior men’s champion in the early 1940s:

“It is a pleasure for me to return to Minneapolis and skate on the best ice in the United States.”

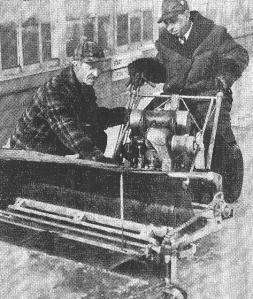

That was high praise for Elmer Anderson and Gotfred Lundgren, the park board employees who maintained the track at Powderhorn using this sweeper, a tractor-drawn ice planer and a bucket of warm water.

The ice sweeper that cleaned the Powderhorn speed skating track in the 1940s. Elmer Anderson (left) and Gotfred Lundgren kept the track in top shape.

They began to prepare the track 3-4 days before a meet by sprinkling it with water a few times. Then they’d pull out a tractor and a plane—a 36-inch blade—to smooth out any bumps from uneven freezing. The biggest problem was cracks in the ice. So the day before the race, Elmer and Gotfred would spend 8-10 hours filling small cracks by pouring warm water into them.

At times their crack-filling work continued right through the races. When large crowds showed up, and for some races attendance surpassed 20,000, the ice tended to crack more often. If Elmer or Gotfred spotted a crack during a race they’d hustle out with a bucket of water after skaters passed and try to patch it. The sweeper was used to remove light snow from the track.

Elmer and Gotfred, who began working for the park board on the same day 18 years before this picture was taken, agreed that the most speed skating records were set when the air temperature was about 30 degrees, which raised a “sweat” on the ice and produced maxiumum speed.

(Source: an undated newspaper clip in a scrapbook kept by Victor Gallant, the park keeper for many years at Kenwood Park, Kenwood Parkway and Bryn Mawr Meadows.)

It’s no wonder that speed skating (as well as hockey) eventually moved indoors to temperature-controlled arenas. But wouldn’t it be fun to see a big race at Powderhorn again?

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Comments (35)

Comments (35)