Cleveland’s First Residential Commission in Minneapolis?

Today I’m reposting an article on the creation and demise of Oak Lake Park as a pricey residential neighborhood on the near north side of Minneapolis in the 1870s. Oak Lake itself sat exactly on the site of today’s Farmers’ Market on Lyndale Avenue. I wrote it in 2011 when the Minnesota Vikings were thought to prefer the Farmers’ Market site for a new stadium. Of course that new stadium was eventually built on the site of the old Metrodome, so that focus of the article is outdated. But the historical information on the site as one of Minneapolis’s first upscale residential developments is still accurate. Not many people know of the ritzy history of the site where the market now stands.

I had set this post aside originally because I had intended to make the case that Horace William Shaler Cleveland was likely the man who advised Samuel Gale on the layout of the new neighborhood. The curving streets adapted to the topography are certainly hallmarks of Cleveland’s work–as are the parcels of land set aside for parks. It is also clear that Cleveland and Gale knew each other. Cleveland’s participation in the Oak Lake development is informed speculation on my part; I have found no documentary evidence of his hand in the project.

The most intriguing part of this post is my surmise that what killed the upscale Oak Lake neighborhood was the creation of the Minneapolis park board. With the acquisition of shores on larger lakes as public park land, wealthy Minneapolitans suddenly had even more attractive sites for their new homes. Without buyers for the larger homes built at Oak Lake, they were eventually divided into rooming houses in a neighborhood that gradually became inhabited by arriving immigrants.

Oak Lake itself was eventually filled in by the park board after it became an unsightly and odiferous hazard.

David C. Smith

Cleveland’s Connections

What brought H.W.S. Cleveland to Minneapolis as a guest lecturer in 1872 may have been his connection to a famous family.

Find the complete story here, an article originally posted in 2011. Since that article was posted, I learned that William’s father, Henry, and Cleveland almost certainly knew each other before Cleveland took on the young engineer as a partner in Chicago. Henry and Horace had both written on the subject of irrigation and were both active in Massachusetts horticultural societies. Their paths would have crossed.

Cleveland later proposed a collaboration in a Minneapolis park with French’s older brother, the famous sculptor Daniel Chester French.

David C. Smith

Minnehaha Creek Mystery Solved!

Park board archivist Angela Salisbury writes:

I believe we’ve solved our mystery. In The Story of the W.P.A. in the Minneapolis Parks, Parkways and Playgrounds volume for 1940 (dated Jan 1, 1941), page 24, regarding the Minnehaha Parkway:

“A small limestone shelter was built north of Minnehaha Creek and west of Xerxes Avenue to house the meter for measuring the amount of sewage entering the city sewer system from the Village of Edina. The village supplied the material for this construction and the work was done by a Park Board W.P.A. crew.”

There is an image of the structure on page 25.

These W.P.A. books are really wonderful, and I’m happy to report they are digitized and available online via the Minnesota Digital Library. This volume is here: https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/p16022coll55:910#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-1177%2C0%2C5267%2C3692

Many wonderful images in these volumes!

Thanks, Angela!

David Carpentier Smith

Cleveland and Olmsted Revisited

In my continuing effort to restore previously mothballed posts about Horace William Shaler Cleveland, I have reposted three articles from several years ago about the relationship of Cleveland and Frederick Law Olmsted. The question is often raised whether Olmsted designed any parks in Minneapolis. My answer is no — especially Washburn Fair Oaks. See why in these posts from Part 1 in 2010, Part 2, and Part 3.

David Carpentier Smith

Minnehaha Creek Shed Mystery

Here’s your new mystery. (Sorry for filling up your inbox today, but this issue was just raised by a reader as I was posting other things!)

The structure pictured below is on park land just north of Minnehaha Creek and west of Xerxes Avenue. That’s just after the creek enters Minneapolis from Edina. I’ve seen it before and assumed it was on private land. I’m told it’s not.

Was it built as a lift station, pump building, or clandestine meeting place for rogue park commissioners? Any Phryne Fishers or Endeavour Morses out there? Or just humble historians?

If you know anything, please share. We haven’t found mention of the structure in park records.

David Carpentier Smith

P.S. I think we should have a televised Geraldo-Rivera-style reveal of the inside of the structure. I suspect it was haunted or there were some enormous (yeti?) footprints discovered in the vicinity. Any record of unexplained pulsating blue lights in neighborhood lore? Or perhaps tiny notes left beside tree stumps as elves are wont to leave ala mr. little guy. TPT?

H.W.S. Cleveland: Old New Posts

A few years ago I deleted several posts on this site about Horace William Shaler Cleveland because I intended to use that information in a biography of Cleveland. I have since been distracted from that project and while I still plan to pick it up again, I thought it useful to re-post some of that information about a man who contributed so much to Minneapolis’s quality of life. So for the next few days I will post some of those hidden historical nuggets about Cleveland and his work in Minneapolis parks. I think much of the information I have discovered about Cleveland’s interactions with Frederick Law Olmsted may also be of interest due to the extensive coverage of Olmsted’s work in the past year.

The first “re-post” is from 2010 when I wrote about the history of plans to connect Lake Calhoun to Lake Harriet by a canal. (When I wrote these pieces about Lake Calhoun that was still it’s legal name. It has since been changed to Bde Maka Ska, but I have not edited those articles to reflect the new name.)

Connecting Lake Harriet and Lake Calhoun

David C. Smith

Horace Cleveland’s House in Danvers

For those who are curious about the house I referred to in my commentary in the StarTribune today in which I praised librarians, here is a photo.

Horace Cleveland lived in this house in Danvers, Mass. from 1857-1868 with his wife, two sons, two servants and his father. His father, Richard Cleveland, died in the house. He was a famous sea captain, one of the early merchant mariners who established a trading route between Salem and China. Sailing that treacherous route around Cape Horn, trading at ports along the way, took Richard Cleveland away from his family for years at a time.

The house did not appear to be occupied, although someone had mowed the grass. When Cleveland lived there, he also owned the five acres around the house. The lot is now 1.5 acres according to Zillow. A freeway passes within 100 yards of the house on the right side of the photo.

It was while living here that H.W.S. Cleveland, already in his 40s, began to look at “landscape gardening” as a profession and had his first commissions. Like his friend and colleague in later life, Frederick Law Olmsted, Cleveland was a farmer as a young man. In fact, they exhibited their produce at some of the same horticulture fairs years before either was associated with landscape architecture.

Danvers town archivist Richard Trask helped me piece together clues from Cleveland’s correspondence that led to us finding the house.

Cleveland’s home before he moved to Danvers is much more famous — but not because Cleveland lived there. The previous occupant of that house in Salem, Mass. wrote one of the most famous American novels while living there. The book was The Scarlet Letter, the author was Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hawthorne’s wife, Sofia Peabody, was a friend of Cleveland’s going back to their childhood.

The white plaque on the corner of the house tells the story.

The amount of information one can get by searching — and asking librarians or archivists for help — is truly astonishing.

David C. Smith

Dean Parkway History

I was asked yesterday about the history of Dean Parkway, the short parkway that connects the west side of Lake of the Isles to Bde Maka Ska from the southern shore of Kenilworth Lagoon to Lake Street. I’ve provided below a brief history of the parkway, which I originally wrote for the Minneapolis Park and Receation Board (MPRB) in 2008. MPRB’s website–minneapolisparks.org–provides histories of most parks in the system, but some of the parkway histories were dropped when the website was redesigned some time back. The Park Board’s website still provides historical information on most park properties and they continue to update my original drafts with recent developments.

I will review the historical information at the MPRB site to see if any other parkway histories could be posted here. I have already posted the original histories I wrote for East River Parkway and West River Parkway.

A historical note: the Dean Parkway history as well as others were written before the name of Lake Calhoun was changed to Bde Maka Ska. I have not gotten around to editing my old drafts to reflect that change. Someday!

Dean Parkway

Location: SW corner of Lake of the Isles to NW corner of Lake Calhoun

Size: 13.02 acres

Name: Named for Joseph Dean, an early settler in Minneapolis, whose children donated most of the land for the parkway.

Acquisition and Development

Park board records list the official date of the acquisition of Dean Parkway, which connects Lake of the Isles to Lake Calhoun, as July 6, 1892. But that date doesn’t tell the whole story.

Joseph Dean, his son, Alfred Dean, and others had offered to donate land to the park board for a lake-area parkway as early as October 1884. The original proposition was to donate land from Hennepin Avenue (which at that time was a parkway!) to Lake Calhoun—what is now Lake Street—and from Lake Calhoun to Lake of the Isles.

According to the 1892 annual report, the donation was accepted, in part, in 1887. (The annual report of 1886 already included Dean Parkway in the description of Lake of the Isles Boulevard and the 1887 annual report broke out the length of Dean Parkway—1.1 miles at the time—from the rest of the Lake of the Isles parkway.) The land connecting Calhoun and Isles and a 1200-foot strip of land along the north shore of Lake Calhoun was accepted from the Deans, but there were strings attached. The donors of the land asked that a road be opened along the entire length of the parkway by October 1, 1887. “That condition has never been complied with,” the board reported in the 1892 annual report, “because of more urgent calls for the expenditure of park funds in other directions.”

Attempts to resolve the issue were a bit messy from the start. In July 1889, Charles Loring, who had negotiated the original donation of the Dean’s land, as well as the donation of most of the shore of Lake of the Isles, perhaps a bit embarrassed that terms he had negotiated had not been complied with by the board, called the board’s attention to the matter of the delayed improvements. A month later park superintendent William Berry provided the board an estimate of the cost of building a 40-foot-wide parkway: $3,530. It was money the park board wouldn’t spend.

But there was another issue that complicated the affair: the track of the Chicago, Minneapolis and St. Paul Railroad crossed the land and a parkway would have to pass under those tracks, which had been built up over low-lying land. In late 1889, the park board began discussions with the railroad about building the drive under their track.

In 1890 and again in 1891, the heirs of Joseph Dean asked that the parkway be built as promised. The apparent patience of the Deans may have been rewarded along the way, however, by none other than Charles Loring. In November 1889, the park board had authorized Loring to negotiate with the owners of land lying between Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet to acquire a parkway connecting those lakes. The owners of the largest piece of that land were the Deans. The park board’s instructions to Loring in those negotiations were to buy the land at the best price he could, but not to exceed $55,000 for the parcel owned by the Deans.

When Loring returned to the park board in January 1890 with an agreement to purchase the Dean’s land for what eventually became William Berry Park, he had agreed to pay them $77,000. The possibility that Loring had agreed to sweeten the deal for the Deans, perhaps as a reward for their patience over Dean Parkway, is suggested by the fact that the other parcel of land needed for William Berry Park was purchased for $36,000 from the Ueland family—exactly the “not to exceed” price specified by the board in Loring’s instructions.

The Dean’s may have received some additional compensation for their patience with the board when they sold to the board in 1891 the two blocks of land connecting east Calhoun and east Isles, which they had at one time donated. The park board had abandoned that donation, where the channel connecting the lakes was eventually built, so it could be replatted to straighten a proposed parkway there. The purchase price for that land was $22,565, payable without interest over ten years. But in a deal that was always perhaps too complicated, the Deans agreed to pay back up to half that amount through assessments on their remaining property in the vicinity.

The park board’s annual report in 1892 reported what seemed to be the happy conclusion of the acquisition of the Dean’s land connecting the lakes on the east when it reported that the “missing link” of the southwestern parkway system finally had been acquired. The report continued that the land “will certainly be of inestimable value should the discussed project of connecting these lakes by a canal be consummated.” This is the first mention in park board documents of the linking of Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun, which was eventually done in 1911.

The extent of Loring’s involvement in the resolution of the Dean Parkway issue was clear when, after the board and the Deans reached agreement on building the parkway in 1892, the Deans informed the board that they had executed a warranty deed for the property for the park board and left it in the possession of Charles Loring who would deliver it to the park board after a carriage drive was constructed over the property. What makes that action remarkable is that at the time Loring was no longer a park commissioner.

The railroad bridge over Dean Parkway, which had held up construction for some time, was not completed until 1896. Bridges over and under railroad tracks were a significant cost in the creation of the park system. For instance, the land for Dean Parkway was mostly donated and the initial parkway construction cost roughly $3,500, but the one railroad bridge cost more than $5,200.

Park superintendent Theodore Wirth submitted a plan in 1910 to improve the parkway and recommended in 1913 that the plan be executed, in part because the railroad had built a new concrete bridge over the parkway and the dredge working in Lake Calhoun had deposited on the northwest shore of the lake considerable fill needed for the parkway. The road work, which would cost nearly $8,000, was begun in 1914, at which time more than 55,000 cubic yards of fill were used from the Calhoun dredging. The road and walks were completed to subgrade and finished the next year.

At the time, park superintendent Theodore Wirth suggested that with the ground filled and leveled it could at some time become a playground. Wirth later referred to the improvements to Dean Parkway as an example of how swamps could be drained and how once-impassable roads could be made among the best in the park system.

In 1951 the City Engineering Department completed a new arrangement of the intersection of Dean Parkway with Lake Street, complete with traffic signals, intended to alleviate traffic problems.

Dean Parkway was not finally paved until 1972. The most recent improvements to Dean Parkway, including repaving and traffic calming measures were completed in 1996.

Trivia

The 750 feet of road from Dean Parkway to Cedar Lake over the tracks of the then Minneapolis and St. Louis Railroad did not become a part of the Grand Rounds until 1929. That year the city and the railroad paid for the park board to pave the short connecting strip and it was turned over to the park board as part of the parkway system. The connection had long been planned but never took place officially until then. Park superintendent Theodore Wirth had campaigned for the strip to be turned over to the park board as early as 1920. The park board had submitted a plan to the city planning commission in 1923 to make that connection as the park board was contemplating the acquisition of the east and north shores of Cedar Lake.

David Carpentier Smith

Rails, Trails, and Sorrow

My park-related reading and the death of an important Minnesotan converged last week.

I was reading Peter Harnik’s From Rails to Trails: The Making of America’s Active Transportation Network due to my interest in the movement that led to the creation of the Cedar Lake Trail and the conversion of the Stone Arch Bridge into a pedestrian and bicycle trail. Reading about converting railroad tracks to trails took me back to one of my favorite books this year, Escape Artist: The Nine Lives of Harry Perry Robinson by Joseph McAleer. Harry Robinson, among several lifetimes (nine!) worth of accomplishments, was an advocate for creating all those railroads in the late 1800s.

As I was contemplating the efforts to create, then repurpose railroads, I saw the obituary for John Helland and an accompanying tribute to him by Dennis Anderson in the StarTribune . Helland was a retired research and policy analyst for the Minnesota Legislature. What McAleer, Harnik and Helland have in common — superficially, at least — is that I met them through these pages. Rich compensation for work that is otherwise not remunerated. They all wrote to me with questions or comments on my posts here, some of which were public and attributed, others exchanged privately in-person or by email.

I wrote a few months ago that I looked forward to reading McAleer’s biography of Harry Robinson, an Englishman who put his stamp on Minneapolis in the 1880s as a journalist, friend to the powerful, and son-in-law of one of Minneapolis’s most influential men, Thomas Lowry. The book lived up to my expectations as it unfolded the story of Robinson’s journey from itinerant Oxford grad to gold prospector to journalist who was knighted for reporting from the trenches of World War I to spokesman for the expedition that discovered and opened King Tut’s tomb. Robinson had more adventures than you or I and he also wrote brilliantly about those adventures, other pressing issues, and the sometimes unsettling prejudices of his time. McAleer chose wisely in sharing freely with his readers the power and wit of Robinson’s own writing through frequent quotations and excerpts from Robinson’s journalism, correspondence, and fiction. Robinson’s considerable influence was due to his writing skill and it is appropriate that his biographer gives us the flavor of that writing.

It was Robinson’s role of railroad advocate — he founded The Northwestern Railroader, a Minneapolis-based magazine in the 1880s and was later the editor of the Chicago-based Railway Age — that resonated as I read Harnik’s book. Harnik was the cofounder of Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, which advocates converting abandoned railroads to recreation trails. He tells the story of the movement to repurpose an asset at one stage of our history into a quite different asset in a quite different time. Among the projects he mentions are not only the Stone Arch Bridge and Cedar Lake Trail in Minneapolis but also the Cannon Valley Trail in southeastern Minnesota. Harry Robinson was a champion of clearing the land and laying the track, Harnik was a champion of acquiring those same ribbons of land when they no longer carried trains and resurfacing them for recreational use. Both saw value in those strips of land that crisscrossed nearly every county in the country.

Of particular note was that Robinson and Harnik both recognized the necessity of grass roots activism to achieve their objectives. Robinson helped organize “railroad men” into local clubs that largely supported railroad management and their preferred political candidates. Robinson claimed the clubs he helped organize were non-partisan but they generally served Republican interests. After McKinley defeated Bryant in the 1896 presidential election, the new President personally thanked Robinson for his support and organizing efforts on his behalf.

Harnik’s conservancy also recognized the necessity of local champions of rail trails and also asserted its non-partisan nature — more accurately so than Robinson. He cites many examples of cooperation from both sides of the political fence. As different as their objectives appear to have been, I think its fair to say that Robinson and Harnik believed they worked for a common good and both sought allies on carefully targeted issues rather than broader ideological causes.

I was also struck by Robinson’s observations of Americans from his privileged position in English society. McAleer writes, “The American character and can-do spirit had impressed him [Harry] deeply. Twenty years later, Harry reflected on ‘the notion that every American is, without any special training, by mere gift of birthright, competent to any task that may be set him.'”

While our history carries ample warnings of the dangers of an over-zealous belief in American exceptionalism, Harry Robinson’s observations seem corroborated by Peter Harnik’s accounts. He cites many examples of people without prior qualifications taking it upon themselves to organize, plan and execute efforts to secure old railroad beds, tunnels and bridges for public use. In many cases they stood against the formidable might of railroad corporations and at times intransigent public and private bureaucracies. Harnik’s heroes come from all corners of private and public life, from those who had profit and non-profit motives as well as those who really didn’t care much about motives but saw something they thought needed doing and, as Harry Robinson would have appreciated, thought they could do.

As I consumed this stew of railroads and trails, non-partisan commitment to service, and the constantly evolving notion of the public good — against a backdrop of great adventures — came the news that John Helland had died. Dennis Anderson laid out the details of Helland’s service to Minnesota as the legislative staff person responsible for writing many of the state’s environmental and conservation laws. Anderson noted that Helland “and others like him in government, are the dutiful — and smart — ones who write the laws and policies that legislators oftentimes can only imagine.” Anderson also applauded Helland’s professional non-partisanship.

I was especially pleased that Anderson included “smart” in his description of Helland and others like him in government. From my own service in the federal government and from working closely with people in local government service, from municipal to park to library employees, I have enormous respect for employees in the public sector. Their work is in many respects more difficult than work in the private sector because they work for so many bosses and must serve, or at least consider, so many competing agendas. Yet they accomplish so much with intelligence and grace. As did John Helland.

Sir Harry Perry Robinson’s life, apart from adventure and glamor, is at its core a worthwhile jumping off point for consideration of so many pertinent contemporary issues: economics, politics and government, heritage, journalism, relations among nations, and more. Whether we agree or not with his views today, they are threads in the tapestry we have become. McAleer’s book about a man and Harnik’s book about a movement compel us to think about how we define and balance private gain and public good. Helland’s legacy, perhaps even more than the natural resources he helped conserve, is his example of how to pursue that balance.

Hall’s Island Redux

With the Park Board’s request yesterday for input on plans for the new Graco Park at Hall’s Island, I thought it might be a good time to pull out of mothballs my original post on the history of Hall’s Island. The following was originally published in 2012 as The Re-creation of Hall’s Island: Part I. I have restored the link to the original post here, if you’d prefer. I had removed the post from the website because I intended to write much more about changes to the river, but that project is on hold for now and I think this information may be useful as background to those considering the history and the future of the island and surroundings. I must admit that this is one of my favorite posts.

The Re-creation of Hall’s Island: Part I (originally published March 14, 2012)

Before he saved enough money to go to medical school, Pearl Hall’s job as a teenager in the mid-1870s was pitching wood onto a cart at a lumber yard near the Plymouth Avenue Bridge on the east bank of the Mississippi River. He remembered vividly from those days of hard labor what he called a little steeple of land sticking out of the Mississippi near the bridge. He could see the tiny patch of ground when he stood on top of his loaded wagon–and he saw the little steeple gradually grow.

What Pearl Hall saw from his perch of pine was the beginning of Hall’s Island, the island that as Dr. P. M. Hall he would eventually acquire and turn over to the city, the island that became the site of a popular municipal bath house, the island that eventually was dredged onto the east bank of the great river, and the island that the Minneapolis park board will soon begin to re-create as the first step in its RiverFIRST development plan.

Hall didn’t think about that little speck of land again until he was elected to be Minneapolis’s Health Officer in 1901. Then he wrestled with the problem all health officers everywhere wrestled with and usually lost to: how to dispose of garbage. Not just coffee grounds, melon rinds, and chicken bones, but real garbage — offal, dead horses, night soil — where death could take took root and grow.

Read more »Wirth Lake Mystery Structure

Rod Miller asked if I knew what this was. I didn’t.

The concrete structure lies west of Wirth Lake between the lake and Theodore Wirth Parkway north of the remnants of the Loring Cascade.

Could it have been a storage facility or root cellar when the park board’s nursery was located in Wirth Park? The nursery was originally established there in the early 1900s on the suggestion of William Folwell to reduce the cost of acquiring the trees being planted throughout the city.

Or was it a structure related to the former farm on the site? The farm house served as a residence for the park board horticulturist unti the mid-1960s. Why was the structure built below grade? Do the concrete construction method or metal grates in the roof help to date the structure?

It is apparently not related to the artificial Loring Cascade which was built in the 1918 and relied on water pumped from the lake. Nor was it likely part of later efforts–beginning in the late 1950s–to pump water from Bassett’s Creek to the Chain of Lakes. There is no sign of the piping that would have been required in those efforts and the structure is probably too far north and west to have been part of those projects.

If you know what the concrete structure was used for and when it was built, please post a comment.

David Carpentier Smith

Broken Tackle: Fritz Pollard and Pudge Heffelfinger

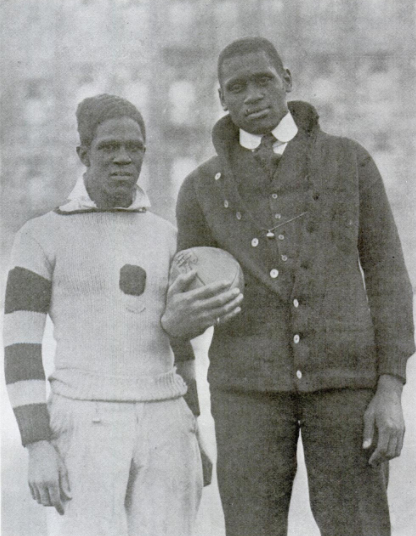

In the course of research that resulted in Joe Lillard Superstar in these pages a few days ago, I came across an anecdote that I thought was funny involving another athlete with Minnesota connections, Pudge Heffelfinger. The story recalled the time Heffelfinger met Fritz Pollard at a reunion of players who had been named to Walter Camp’s All-America football teams.

William Heffelfinger, known from childhood as “Pudge,” was the son of C.B. Heffelfinger whose men’s shoe store had been on Bridge Square in Minneapolis since the late 1860s. Pudge played football with crushing physicality and was a behemoth for his day at 6’3″ and 195 pounds. His day was late 19th Century. He was a three-time All-America tackle at Yale 1889-1891 and is often considered the first professional football player. He allegedly was already receiving “double expenses” when he played for the Chicago Athletic Association in 1892, but when the Allegheny Athletic Association team of Pittsburgh was preparing to play their Pittsburgh rivals they offered Heffelfinger $500 to take the train down from Chicago and help them win, which he did. He recovered a fumble and returned it for the game’s only score.

Frederick Douglas “Fritz” Pollard was a kid from the north side of Chicago who became an All-America halfback at Brown University in 1916. In 1920 Pollard was one of the first two Black players in what became the NFL along with Bobby Marshall from Minneapolis Central High School and the University of Minnesota. Pollard also became the first Black coach in the NFL with the Akron Pros in 1921. Pollard was 5’9″ and about 165 but had firefly — now-you-see-me-now-you-don’t — elusiveness.

The story goes that Heffelfinger was introduced to Pollard at the reunion dinner for many of the greatest players in the history of the game in the 1920s. Players of that stature often have, shall we say, an abundance of self-confidence as well as an ease with the playful banter of the locker room. Heffelfinger, then in his 50s was probably still his full youthful height but if he was like most men, he had augmented his playing weight by a belt notch or two. Pollard was in competitive shape, but still six inches shorter. The difference in size prompted Heffelfinger to comment as they shook hands, “Mr. Pollard, if you were playing in my day, I think I might have broken you in two.” Pollard responded with a smile, “Mr. Heffelfinger, I don’t think you could have broken my stride.”

Apocryphal? Maybe. But who cares, its a great story. It’s the kind of retort I wouldn’t have thought of until the next day!

Heffelfinger became a successful real estate developer in Minneapolis and infuential in Minnesota politics. The Heffelfinger name is preserved in Minneapolis parks by an Italian fountain in the Rose Garden which was donated to Minneapolis parks in 1947 by Frank Heffelfinger, Pudge’s brother.

David Carpentier Smith

Comments (4)

Comments (4)