Archive for the ‘H.W.S. Cleveland’ Tag

Riverside Park Staircase

I received a question from Elliot about Riverside Park that I can’t answer. Maybe you can.

“There are two limestone structures to the left and right of the main staircase at Riverside Park. They’re pretty overgrown. They look staircase-like, but I wonder if they were cascades for water to go down? I looked but couldn’t find any old pictures. Do you know about these?”

Any thoughts?

Riverside Park was one of four neighborhood parks designated by the first Board of Park Commissioners when the Board was created by the Minnesota Legislature in 1883. They designated a new neighbornood park in each quadrant of the city. The others were Central (Loring) Park, Logan Park and Farview Park. In addition to the neighborhood parks, the board planned to acquire connecting parkways–thanks to H.W.S. Cleveland’s plans–as well as land around one of the distant lakes to the southwest. Before it was officially named, the Park Board refered to it as Sixth Ward Park.

The neighborhood near Riverside Park was the only one that already had a park at that time although it served mostly as a pasture. Murphy Square, which had been donated to the city as a park nearly 30 years earlier, stood only a half-mile to the west of Riverside Park.

You can read a brief history of Riverside Park at the Park Board’s website. Click on the “History” tab.

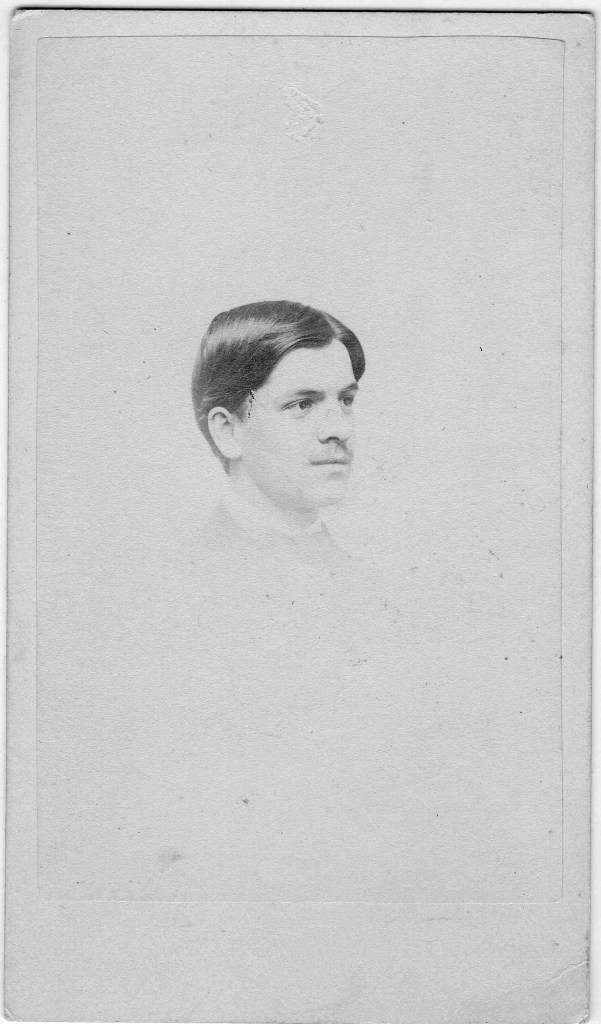

David Carpentier Smith

After Careful Consideration: Horace W. S. Cleveland Overlook

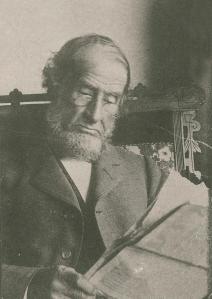

The man who first suggested putting Horace William Shaler Cleveland’s name on something in the Minneapolis park system was William Folwell, the president of the Minneapolis Park Board in 1895. Folwell noted in the annual report of that year that due to Cleveland’s advanced age, then 81, he was no longer able to assist in the development of park plans. Folwell then recommended, “In some proper way his name should be perpetuated in connection with our park system.”

Last week the Minneapolis Park Board acted on Folwell’s advice and named a river overlook near East 44th Street on West River Parkway the “Horace W. S. Cleveland Overlook.”

Cleveland was already 58 years old when he was invited to come to Minneapolis from Chicago to give a public lecture at the Pence Opera House on Bridge Square in 1872. He spoke on how to improve the city through landscaping. He was a big hit and his advice was sought in St. Paul and Minneapolis on how to improve the cities. He wrote an influential book based on his lectures, Landscape Architecture as Applied to the Wants of the West. That began his association as an influential advisor to both cities. When the Minnesota legislature created the Minneapolis Park Board in 1883, one of its first acts was to hire Cleveland to give his advice on what needed to be done.

He produced a report complete with a map, which he called Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis. His map showed a continuous parkway connecting Lake Harriet with Loring Park, then north to Farview Park, directly east past Logan Park in northeast Minneapolis, then south back to the Mississippi River Gorge near the University. His parkway continued on both sides of the river from Riverside Park out to Lake Street and then all the way back west to what is now Bde Maka Ska. It was the brilliant original imagining of what would become the Grand Rounds. It helped instill the notion that parks are not isolated parcels of land but form a part of a “system” that is integral to the quality of life and well-being in a city.

Cleveland had seen the struggles of older Eastern cities such as Boston and New York to create parks in already crowded urban areas. He had worked in the park system in Chicago and saw the same struggles to create open spaces in built environments. He had long argued in Minneapolis and St. Paul to create parks while undeveloped land could still be acquired at reasonable cost and features of natural beauty could still be preserved for public enjoyment. That we have such wonderful open spaces and preserved nature in our cities today owes much to Cleveland’s vision.

It is especially appropriate that an overlook of the river gorge be connected with Cleveland’s legacy. He had an affection and admiration for the beauty of the unique river gorge above all other of “nature’s gifts” to Minneapolis and St. Paul. He argued eloquently for the preservation of the natural riverbanks, calling the heavily wooded, still-unscarred river gorge a setting “worthy of so priceless a jewel” as the mighty river. Both St. Paul and Minneapolis heeded his advice.

The setting is still worthy of the jewel. Even though most of the color is gone from the wooded river banks, you might want to visit the Mississippi River overlook. Or at least cross over one of the river bridges and marvel at the beauty that has been preserved in part due to the vision and persistence of Horace William Shaler Cleveland, which is finally properly acknowledged.

David C. Smith

H.W.S. Cleveland Trivia

I’ve restored a couple more Cleveland-related pages written long ago.

One pertains to the famous men Horace William Shaler Cleveland knew as his older brother’s best friends, including two men who have Minneapolis parks named for them. It is likely that the views of these soon-to-be famous men influenced Cleveland’s thinking on many issues. But it is also entirely possible that Cleveland’s experiences and observations as a young man — especially from his travels to the “West” — could have influenced them as well.

Another post provides Cleveland’s recommendations for books to read on landscape gardening. The list is taken from a letter he wrote to the secretary of the Minneapolis park board nearly 140 years ago — so some of the views expressed may seem outdated. All of the books Cleveland recommends, once scarce in the United States, are now available free on Google Books.

For a man without much formal education, Cleveland was an intellectual force.

Davd Carpentier Smith

Cleveland’s Property and Olmsted’s Fame

I mentioned a couple weeks ago the friendly relationship between Horace William Shaler Cleveland and Frederick Law Olmsted. While there is so much of note in that relationship, and dozens of letters exchanged between the men attest to it, one of Cleveland’s letters to Frederick Law Olmsted caught my attention because it referred to property Cleveland owned. Later while studying an old plat map of Minneapolis I stumbled across an undivided, 4.7-acre plot of land in South Minneapolis labelled as owned by Cleveland. Like finding a needle in a haystack, I suppose. Another slice of my research into Cleveland’s life which I had previously posted.

Epilogue: Even though he owned some property and worked well into his 80s, Cleveland’s money did run out. His former partner, William Merchant Richardson French, when he was the director of the Chicago Art Institute, sent a letter to Cleveland’s colleagues and friends–including Olmsted–asking for donations to help Cleveland pay his bills as an elderly man.

More to come.

David C. Smith

More Cleveland: Samuel Gale, Oak Lake, Kenwood Parkway

After writing about the Oak Lake Addition in North Minneapolis in 2011, I augmented what I knew about H.W.S. Cleveland’s relationship with Samuel Gale and his work at Oak Lake in “Horace Cleveland Hated Rectangles.” I also wrote more about Cleveland’s eventual work for the Minneapolis park board at Oak Lake and his ideas about Kenwood Parkway.

These are another two archived posts pertaining to Cleveland’s life and work that I just reactivated.

David C. Smith

Cleveland’s First Residential Commission in Minneapolis?

Today I’m reposting an article on the creation and demise of Oak Lake Park as a pricey residential neighborhood on the near north side of Minneapolis in the 1870s. Oak Lake itself sat exactly on the site of today’s Farmers’ Market on Lyndale Avenue. I wrote it in 2011 when the Minnesota Vikings were thought to prefer the Farmers’ Market site for a new stadium. Of course that new stadium was eventually built on the site of the old Metrodome, so that focus of the article is outdated. But the historical information on the site as one of Minneapolis’s first upscale residential developments is still accurate. Not many people know of the ritzy history of the site where the market now stands.

I had set this post aside originally because I had intended to make the case that Horace William Shaler Cleveland was likely the man who advised Samuel Gale on the layout of the new neighborhood. The curving streets adapted to the topography are certainly hallmarks of Cleveland’s work–as are the parcels of land set aside for parks. It is also clear that Cleveland and Gale knew each other. Cleveland’s participation in the Oak Lake development is informed speculation on my part; I have found no documentary evidence of his hand in the project.

The most intriguing part of this post is my surmise that what killed the upscale Oak Lake neighborhood was the creation of the Minneapolis park board. With the acquisition of shores on larger lakes as public park land, wealthy Minneapolitans suddenly had even more attractive sites for their new homes. Without buyers for the larger homes built at Oak Lake, they were eventually divided into rooming houses in a neighborhood that gradually became inhabited by arriving immigrants.

Oak Lake itself was eventually filled in by the park board after it became an unsightly and odiferous hazard.

David C. Smith

Cleveland’s Connections

What brought H.W.S. Cleveland to Minneapolis as a guest lecturer in 1872 may have been his connection to a famous family.

Find the complete story here, an article originally posted in 2011. Since that article was posted, I learned that William’s father, Henry, and Cleveland almost certainly knew each other before Cleveland took on the young engineer as a partner in Chicago. Henry and Horace had both written on the subject of irrigation and were both active in Massachusetts horticultural societies. Their paths would have crossed.

Cleveland later proposed a collaboration in a Minneapolis park with French’s older brother, the famous sculptor Daniel Chester French.

David C. Smith

Cleveland and Olmsted Revisited

In my continuing effort to restore previously mothballed posts about Horace William Shaler Cleveland, I have reposted three articles from several years ago about the relationship of Cleveland and Frederick Law Olmsted. The question is often raised whether Olmsted designed any parks in Minneapolis. My answer is no — especially Washburn Fair Oaks. See why in these posts from Part 1 in 2010, Part 2, and Part 3.

David Carpentier Smith

H.W.S. Cleveland: Old New Posts

A few years ago I deleted several posts on this site about Horace William Shaler Cleveland because I intended to use that information in a biography of Cleveland. I have since been distracted from that project and while I still plan to pick it up again, I thought it useful to re-post some of that information about a man who contributed so much to Minneapolis’s quality of life. So for the next few days I will post some of those hidden historical nuggets about Cleveland and his work in Minneapolis parks. I think much of the information I have discovered about Cleveland’s interactions with Frederick Law Olmsted may also be of interest due to the extensive coverage of Olmsted’s work in the past year.

The first “re-post” is from 2010 when I wrote about the history of plans to connect Lake Calhoun to Lake Harriet by a canal. (When I wrote these pieces about Lake Calhoun that was still it’s legal name. It has since been changed to Bde Maka Ska, but I have not edited those articles to reflect the new name.)

Connecting Lake Harriet and Lake Calhoun

David C. Smith

Horace Cleveland’s House in Danvers

For those who are curious about the house I referred to in my commentary in the StarTribune today in which I praised librarians, here is a photo.

Horace Cleveland lived in this house in Danvers, Mass. from 1857-1868 with his wife, two sons, two servants and his father. His father, Richard Cleveland, died in the house. He was a famous sea captain, one of the early merchant mariners who established a trading route between Salem and China. Sailing that treacherous route around Cape Horn, trading at ports along the way, took Richard Cleveland away from his family for years at a time.

The house did not appear to be occupied, although someone had mowed the grass. When Cleveland lived there, he also owned the five acres around the house. The lot is now 1.5 acres according to Zillow. A freeway passes within 100 yards of the house on the right side of the photo.

It was while living here that H.W.S. Cleveland, already in his 40s, began to look at “landscape gardening” as a profession and had his first commissions. Like his friend and colleague in later life, Frederick Law Olmsted, Cleveland was a farmer as a young man. In fact, they exhibited their produce at some of the same horticulture fairs years before either was associated with landscape architecture.

Danvers town archivist Richard Trask helped me piece together clues from Cleveland’s correspondence that led to us finding the house.

Cleveland’s home before he moved to Danvers is much more famous — but not because Cleveland lived there. The previous occupant of that house in Salem, Mass. wrote one of the most famous American novels while living there. The book was The Scarlet Letter, the author was Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hawthorne’s wife, Sofia Peabody, was a friend of Cleveland’s going back to their childhood.

The white plaque on the corner of the house tells the story.

The amount of information one can get by searching — and asking librarians or archivists for help — is truly astonishing.

David C. Smith

Horace William Shaler Cleveland and Me at the Library

The temperature will rise just enough on Saturday to allow you out to hear me speak on my favorite subject: Horace William Shaler Cleveland, the landscape architect who shaped the Minneapolis and St. Paul park systems in the 19th Century and beyond.

Come to the Minneapolis Central Library at 2:00 pm, Saturday, January 6 to hear the latest on the surprising life and career of “Professor” Cleveland. I’ve travelled the country for the last three years piecing together the life of this remarkable man who helped shape our thinking on urban parks.

Update: I’m making progress on editing and reorganizing the 270-plus entries on this blog over the last several years, so I hope to re-post most of them in the near future. Until then, we can catch up at the library on Saturday afternoon. Hope to see you there. There should be plenty of time to consider any other park-related topics or questions you might have.

David C. Smith

Behind the Scenes: Minneapolis’s First Park?

You have a rare opportunity in April to tour the greenhouses in one of the first parks in Minneapolis: Lakewood Cemetery.

Technically, the first park in Minneapolis was Murphy Square, which Capt. Edward Murphy donated to the city as a park in 1857, but Murphy Square was used as a pasture for nearly two decades.

Lakewood Cemetery was created in 1871 — 12 years before the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners was created — by many of the same people who helped create the Minneapolis park system. Names such as Loring, Brackett, Morrison and King are as much a part of cemetery history as they are of park history. Lakewood Cemetery even donated some of the land that is now the Thomas Sadler Roberts Bird sanctuary on the north shore of Lake Harriet to the park board. Once when the park board was short of cash, it borrowed money from the cemetery.

H.W.S. Cleveland and Lakewood Cemetery

Another name that links Lakewood Cemetery with Minneapolis parks is Cleveland — but not in the way that many assume. Horace William Shaler Cleveland, whose blueprint guided the development of Minneapolis and St. Paul parks, did not design Lakewood Cemetery, although he designed many cemeteries across the country. In 1884, the cemetery’s trustees hired Ralph Cleveland, Horace Cleveland’s son, as superintendent. The fact that Ralph had no prior experience in such a position and the trustees consisted largely of men who had worked closely with Horace Cleveland in creating the Minneapolis park system suggests that Ralph’s hire may have been a favor to the father. That became a larger issue in the future of Minneapolis parks in 1886 when Horace and Maryann Cleveland moved from Chicago to Minneapolis, in part to be nearer Ralph and his family.

H. W. S. Cleveland

They had good reasons. Horace was 72 at that time and looking to the day when he could no longer perform the often strenuous physical duties of a landscape architect. He was also raising his two young granddaughters, whose father, Horace’s oldest son, Henry, had died of disease in the jungles of Colombia in 1880. And he couldn’t count on help from his wife, Maryann, who was frail and ill much of her adult life. Living near their only surviving child made sense.

I don’t think the St. Paul and Minneapolis park systems would be what they are today if Horace Cleveland had not moved to Minneapolis when he did. He became a strong presence in park debates. The opinions of Professor Cleveland, as he was called, were often quoted in the newspapers, which would have been far less likely if he had remained at the distance of Chicago. Would Minneapolis have acquired Minnehaha Falls without Cleveland’s prodding? Would St. Paul and Minneapolis have acquired the Mississippi River Gorge on both sides of the river without his constant encouragement and dire warnings? Would park commissioners have continued to heed Cleveland’s advice to forego improvements and decorations in the parks in order to buy more land if Cleveland hadn’t been looking over their shoulders? I suspect the answer to one or all of those questions is “No!”

I think a case could be made that Lakewood Cemetery, by hiring Ralph Cleveland as superintendent in 1884, is indirectly responsible for much of the success of the park systems in St. Paul and Minneapolis.

You’re Invited!

From its inception, Lakewood followed the national trend of creating “garden” cemeteries that were designed to be picturesque parks as well as cemeteries. An integral part of the operations of those cemeteries was growing their own flowers and decorative plants in greenhouses. The flowers were planted to beautify the cemetery grounds and were sold for placement on graves.

Lakewood Cemetery retains one of the largest cemetery greenhouse operations in the country raising 95,000 plants annually in two greenhouses. And it is inviting you to take a closer look and learn more about this colorful part of its history at a time when its greenhouses will be at their showiest!

Lakewood Cemetery will conduct tours of its two greenhouses on Earth Day, April 22 from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. There is much more information at lakewoodcemetery.com. You’ll even get to pot a plant to take home!

I encourage you to check out the website, but don’t wait too long. The tours have a limited capacity, so reservations are required. The tour is open to all ages and it’s free, with an optional donation of $5 suggested.

Whether you’re a gardener or a history buff, it sounds like a great opportunity to see something that’s usually out of sight. Spend a couple hours in the morning helping clean up your favorite park — or join the Minneapolis Parks Foundation or Friends of the Mississippi River in their cleanup efforts — and then dash over to Lakewood Cemetery.

While you’re there, pay your respects at the graves of Horace, Maryann and Ralph Cleveland.

David C. Smith

© 2017 David C. Smith

Comments (8)

Comments (8)