Archive for the ‘Mississippi National River and Recreation Area’ Tag

Minnehaha Rails

Rene Rosengren recently sent some photos of metal rails she found south of the Minnehaha Off Leash Dog Park just off the Minnehaha Trail. Any ideas what they are?

I’ve written about the limestone quarry at Minnehaha Park that was operated for just one year by the park board in 1907, but was reopened by the WPA from 1938-1942. I think these tracks are too far south to have been part of that quarry, but the narrow gauge suggests that they were part of a quarry or similar extraction enterprise.

I suspect the tracks were once a part of the Bureau of Mines Research Center on federal land that is now owned by the National Park Service as part of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area.

Rene and I would be happy to hear any thoughts on the narrow gauge tracks.

David Carpentier Smith

After Careful Consideration: Horace W. S. Cleveland Overlook

The man who first suggested putting Horace William Shaler Cleveland’s name on something in the Minneapolis park system was William Folwell, the president of the Minneapolis Park Board in 1895. Folwell noted in the annual report of that year that due to Cleveland’s advanced age, then 81, he was no longer able to assist in the development of park plans. Folwell then recommended, “In some proper way his name should be perpetuated in connection with our park system.”

Last week the Minneapolis Park Board acted on Folwell’s advice and named a river overlook near East 44th Street on West River Parkway the “Horace W. S. Cleveland Overlook.”

Cleveland was already 58 years old when he was invited to come to Minneapolis from Chicago to give a public lecture at the Pence Opera House on Bridge Square in 1872. He spoke on how to improve the city through landscaping. He was a big hit and his advice was sought in St. Paul and Minneapolis on how to improve the cities. He wrote an influential book based on his lectures, Landscape Architecture as Applied to the Wants of the West. That began his association as an influential advisor to both cities. When the Minnesota legislature created the Minneapolis Park Board in 1883, one of its first acts was to hire Cleveland to give his advice on what needed to be done.

He produced a report complete with a map, which he called Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis. His map showed a continuous parkway connecting Lake Harriet with Loring Park, then north to Farview Park, directly east past Logan Park in northeast Minneapolis, then south back to the Mississippi River Gorge near the University. His parkway continued on both sides of the river from Riverside Park out to Lake Street and then all the way back west to what is now Bde Maka Ska. It was the brilliant original imagining of what would become the Grand Rounds. It helped instill the notion that parks are not isolated parcels of land but form a part of a “system” that is integral to the quality of life and well-being in a city.

Cleveland had seen the struggles of older Eastern cities such as Boston and New York to create parks in already crowded urban areas. He had worked in the park system in Chicago and saw the same struggles to create open spaces in built environments. He had long argued in Minneapolis and St. Paul to create parks while undeveloped land could still be acquired at reasonable cost and features of natural beauty could still be preserved for public enjoyment. That we have such wonderful open spaces and preserved nature in our cities today owes much to Cleveland’s vision.

It is especially appropriate that an overlook of the river gorge be connected with Cleveland’s legacy. He had an affection and admiration for the beauty of the unique river gorge above all other of “nature’s gifts” to Minneapolis and St. Paul. He argued eloquently for the preservation of the natural riverbanks, calling the heavily wooded, still-unscarred river gorge a setting “worthy of so priceless a jewel” as the mighty river. Both St. Paul and Minneapolis heeded his advice.

The setting is still worthy of the jewel. Even though most of the color is gone from the wooded river banks, you might want to visit the Mississippi River overlook. Or at least cross over one of the river bridges and marvel at the beauty that has been preserved in part due to the vision and persistence of Horace William Shaler Cleveland, which is finally properly acknowledged.

David C. Smith

Minnesota River Valley National Park?

What does the Minnesota River have to do with Minneapolis parks? The Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners, in 1934, tried to help Minnesota Gov. Floyd B. Olson convince the federal government to acquire the Minnesota River valley from Shakopee to Mendota and make it a national park.

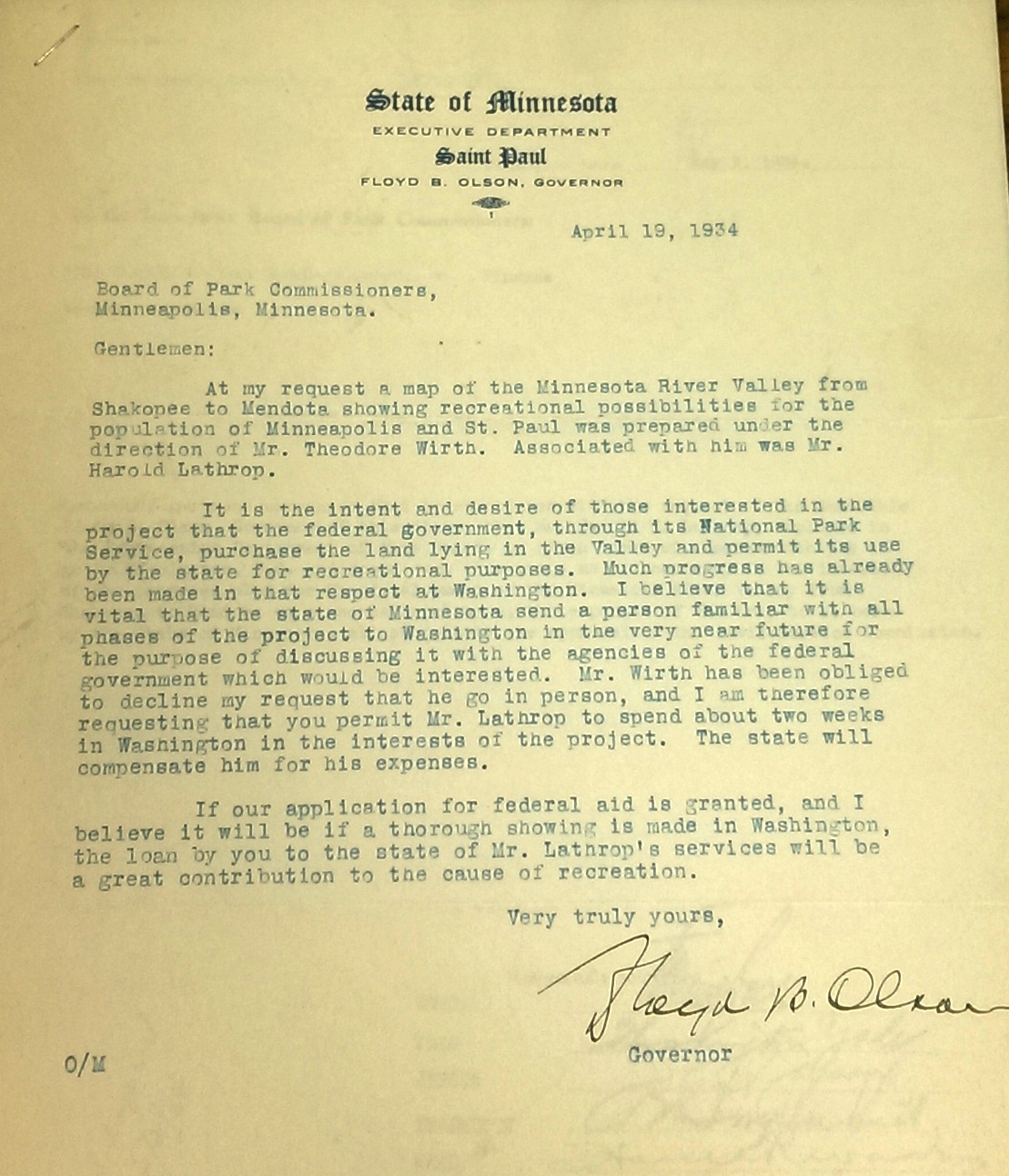

I only have the bare bones of the story, but I wanted to throw them out there so someone else could expand it if so inclined. I find this bit of history particularly interesting in light of important efforts by Friends of the Mississippi River and the National Park Service to protect and preserve our rivers. In 1934, Gov. Olson wrote to the Minneapolis park board asking for assistance. I’ve reproduced the letter in full.

Gov. Floyd B. Olson asked the Minneapolis park board for help in creating a national park of the Minnesota River Valley in April 1934.

Always willing to cooperate on park projects, the Minneapolis park board, with Supt. Theodore Wirth’s support, voted on May 2 to give Harold Lathrop, “an employee in the Engineering Department,” leave of absence with pay to go to Washington, D.C. “and spend such time as is necessary in the interest of the proposed plan.”

It’s obvious from Gov. Olson’s letter that he had already secured the assistance of Wirth and Lathrop, and the park board presumably, in creating a map of the “recreational possibilities” of the area. I have never seen such a map created solely for that purpose, but in 1935, the park board published Theodore Wirth’s Tentative Study Plan for the West Section of a Metropolitan Park System. That report contained a detailed map of all of Hennepin County and more, including the closeup below of the Minnesota River Valley. (The full report and map are appended to the park board’s 1935 annual report.)

Detail of park possibilities in the Minnesota River Valley, Shakopee to Mendota, from a 1935 study plan by Theodore Wirth. Harold Lathrop, a park board employee in the engineering department, assisted Wirth on the report. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

I don’t know what became of Gov. Olson’s idea of a national park when Lathrop went off to Washington, D.C. An update came a month later when, at its June 6 meeting, the park board approved Wirth’s recommendation that Lathrop be given two months leave of absence without pay “to act as Project Director for the Federal Government in connection with the proposed Minnesota River Valley development.”

Barbara Sommer writes in Hard Work and A Good Deal that Lathrop was then hired by the National Park Service, which ran the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a federal work-relief program, to supervise CCC work in state parks in Minnesota. There is no indication that any of that work involved a potential park along the Minnesota River. The young National Park Service employee running the CCC program was Conrad Wirth, Theodore’s middle son. Conrad’s performance in that role set him on a trajectory to become the Director of the National Park Service in the 1960s.

I don’t believe Lathrop ever returned to the Minneapolis park board. From his job coordinating federal work in state parks, he was hired as the first director of Minnesota State Parks less than a year later in July 1935. He held Minnesota’s top state parks job until 1946, when he supposedly retired at age 45. Eleven years later, however, he became the first director of state parks in Colorado. Colorado’s first state park is named Lathrop Park.

That’s all I know of the proposed Minnesota River Valley National Park—an intrigue sparked by one letter from the governor in a correspondence file. If you know more, I’d be happy to hear from you.

David C. Smith

P.S. Timely! Friends of the Mississippi River is hosting a fundraiser tomorrow night — October 4—at the Nicollet Island Pavilion in Minneapolis. Suggested donation $100. Worthy cause! Also read the current StarTribune series on threats to the health of the Mississippi.

Comments (10)

Comments (10)