Archive for the ‘Minneapolis parks’ Category

Where is De Soto Harbor?

With the completion of the High Dam, now the Ford Dam, on the Mississippi River just upstream from Minnehaha Creek in 1917, the Minneapolis park board was pressed to name the new reservoir that formed behind the dam. Without explanation, it settled on the odd name of “De Soto Harbor” on July 3, 1918. I have found no evidence that the name was ever changed, rescinded — or used.

The “High Dam” nearing completion in 1917. It became known as the Ford Dam in 1923. This was before the Ford Bridge was built later in the 1920s. (from City of Parks, Minnesota Historical Society)

The harbor was named for Hernando de Soto, the Spanish explorer who was believed then to have been the first European to see the Mississippi River about 1540. De Soto’s expedition never got anywhere near Minnesota, however, crossing the Mississippi near Memphis, Tennessee. De Soto’s story is one of some “firsts” in European exploration of North America, but also considerable brutality toward native people.

Other names the park board considered for the reservoir were Lafayette Lake, Liberty Lake, Lake Minneapolis and St. Anthony Harbor. (Minneapolis Tribune, June 27, 1918.)

The name chosen was unusual because the park board had not, for the most part, named park properties for people not connected with the history of the city or state. (Logan Park was a notable exception.) The decision to name parks only for people of local historical significance was adopted as an official policy of the park board in 1932. The policy was revised in 1968 to enable Nicollet Park to be renamed Dr. Martin Luther King Park.

Of course, some park features on the Minneapolis map—such as St. Anthony Falls, Lake Harriet, Lake Calhoun, Minnehaha Creek—predate by decades the creation of the park board in 1883.

The park board had been involved in issues surrounding dam construction for years by the time it named the reservoir, first with the Meeker Island Dam and later the “High Dam.” From as early as 1909 the park board had sent representatitives to meetings on high dam construction held by the US Army Corps of Engineers and in 1910 had requested that the park board receive half the electricity generated by the dam in exchange for “flowage rights” over land the park board owned. The government did not agree, even though the park board lost 27 acres of land for the reservoir in 1916. Included in that acreage were several islands in the river. The park board granted rights to cut down timber on one island in the river to a local charity before the trees were submerged. The board noted that neither the park board nor the Corps of Engineers wanted a stand of dead timber in the middle of the new reservoir.

Few photos I have seen give a good picture of water levels in the Mississippi before the dams were built. One of the most dramatic is this one of the Stone Arch Bridge in 1890.

Stone Arch Bridge 1890, before any dams downstream created reservoirs. (Minnesota Historical Society)

I don’t know what month the photo was taken, although foliage says summer. Perhaps the river was unusually low in late summer, but to see the Stone Arch Bridge nearly completely out of the water is unusual.

David C. Smith

You Think a Dog Park Was Controversial?

After holding public hearings and receiving “various communications objecting to it,” on April 20, 1960, the Minneapolis park board rescinded an agreement with Minneapolis Civil Defense to build a “demonstration atomic bomb fallout protective shelter” in Nicollet Park. The board granted permission to build the demonstration fallout shelter at The Parade instead. Was it ever built? I don’t know.

This 1960 instructional booklet included plans for a fallout shelter, presumably similar to the one Minneapolis Civil Defense wanted to build at The Parade. This image is from authentichistory.com. The booklet is also available for sale on e-Bay at the time of this posting–if you’re still worried, or think it would do any good.

In 1968 Nicollet Park was renamed Dr. Martin Luther King Park. The park was the focus of bitter debate over the past year. The issue was whether converting a small portion of the park into an off-leash dog park would desecrate the memory of Dr. King. The dog park was not built.

During the 1960 meeting at which the board approved the fallout shelter, it also granted permission to the Twin City Walk for Peace Committee to hold an open air meeting at The Parade at the conclusion of a “peace walk.”

As a point of reference, Stanley Kubrick’s classic film of the atomic-bomb age, Dr. Strangelove, was released in 1964.

David C. Smith

Minneapolis Park Crumbs I: Morsels Left Behind from Park Research

Outlawed: The possession or sale of heroin, other opium derivates, and cocaine without a prescription. Penalties established of $50-$100 fine or 30-90 days in the workhouse. Minneapolis City Council Proceedings, October 10, 1913.

Approved: Spanish language classes for Central and West high schools. Existing faculty at each school will teach the classes. Action of the Minneapolis School Board reported in the Minneapolis Tribune, January 13, 1915.

Suggested: A cement wall between Lake Calhoun and Lakewood Cemetery if the city would continue to permit ice to be cut from the lake. From Minneapolis Journal article, June 8, 1901, about the visit to Minneapolis of Dr. Henry Marcy, “the eminent surgeon and philanthropist of Boston.” Dr. Marcy made the suggestion when he visited Lake Calhoun with Charles Loring. He said he had heard a great deal about Minneapolis’s parks and had a Minneapolis map on which he had sketched out their locations, but wanted to see them.

Found: Gold in Hennepin County, the best sample near Minnehaha Park. The specimen recovered by Prof. J. H. Breese, a former professor at Eastern universities, was confirmed as gold by state geologist Prof. N. H. Winchell. Prof. Breese believes the particles were carried from higher latitudes during the drift period, “but he is quite confident that all has not yet been found.” Reported by Minneapolis Tribune, July 17, 1889.

Built: A 100-foot steamboat named “Minneapolis” by Hobart, Hall and Company. Will begin running freight between Minneapolis and St. Cloud in late July. The company asked the Board of Trade for a free landing near Bassett’s Creek. Reported by Minneapolis Tribune July 8, 1873. The company planned to build another steamboat for the same route, more if “expedient.”

David C. Smith

Phelps Wyman: Pioneer Landscape Architect and Minneapolis Park Commissioner

Several pioneer landscape architects were associated with Minneapolis parks, from H. W. S. Cleveland, in a very big way, to Warren H. Manning, more modestly, to Frederick Law Olmsted, who once wrote a letter to Minneapolis park commissioners at Cleveland’s request. But only one pioneer landscape architect was also elected to the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners: Phelps Wyman. (He never used his first name, Alanson, so I won’t either.) Wyman’s pioneer status in landscape architecture was determined by Charles A. Birnbaum and Robin Karson in Pioneers of American Landscape Design, which profiles about 150 American landscape architects.

Wyman is also one of a very few landscape architects not employed by the Minneapolis park board to have had designs for Minneapolis parks published in annual reports of the park board. The 1922 annual report presented Wyman’s plan for Douglas Triangle, now Thomas Lowry Park, which I wrote about here. This plan was executed in 1923. Curiously, I can find no record that Wyman was paid for the work.

Wyman’s plan for pools and pergola in 1922 annual report of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners

The next year he had another interesting plan published in the park board’s annual report, but it was never implemented. Wyman’s plan for Washburn Fair Oaks Park across from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA) Continue reading

Horace Cleveland Hated Rectangles

Oak Lake Addition was a rare real estate development in Minneapolis because the streets followed the contour of the land instead of a grid pattern. While I’ve found no evidence of who was responsible for the layout of the addition in 1873, it is reminiscent of Horace Cleveland’s work in St. Anthony Park for William Marshall at about the same time and later in Washburn Park or Tangletown near Minnehaha Creek. Although I find no reference to the project in Cleveland’s correspondence, it is plausible that he was involved in the layout of Oak Lake Addition.

Oak Lake Addition, platted in 1873. 1892 plat map (John R. Borchert Map Library, University of Minnesota)

Samuel Gale, the man who platted the Oak Lake Addition, had his hands in nearly everything in the young city: School Board, Athenaeum and Library Board, Academy of Natural Sciences, Society of Fine Arts, Board of Trade, City Council, the public lecture series, he even sang in the city’s most celebrated quartet along with his brother, Harlow, and it was later claimed that although nearly everyone speculated in real estate in those days, he was the dean of realtors in the city. Given his wide interests and involvement in civic affairs, it would be incredible if Gale hadn’t been one of those who welcomed Horace Cleveland to the city during his first visits in 1872.

In July, 1873 Gale was the chair of the Board of Trade’s committee on parks, which reported that several “public-spirited citizens” planned to devote considerable time to the issue of parks with “Mr. Cleveland, well-known landscape gardener” before the next Board of Trade meeting. (Minneapolis Tribune, July 18, 1873.) I think it is safe to assume that Gale himself was one of those who planned to meet with Cleveland. So it appears almost certain that Gale and Cleveland knew each other and had likely discussed park issues before Gale produced his plat for the Oak Lake Addition.

Absent information on who designed Oak Lake Addition, it’s fun to speculate that Cleveland may have had a hand in it, or at least influenced it through the book he published in early 1873, Landscape Architecture as Applied to the Wants of the West. In his classic of landscape architecture, Cleveland expressed his distaste for the grid pattern of streets in so many cities, because it ignored “sanitary, economic and esthetic sense.”

“Every Western traveller is familiar with the monotonous character of towns resulting from the endless repetition of the dreary uniformity of rectangles,” he wrote.

While he singled out western cities — it was his book’s theme — it takes only a glimpse of a map of Manhattan to know that rectangularism was not a sin peculiar to the frontier. For New York, however, it was already too late to do anything about that “dreary uniformity”; the West still had a chance to get it right. Cleveland added that “even when the site is level” the rectangular fashion of laying out cities “is on many accounts objectionable.”

He suggested that if blocks had to be rectangular at least they should be Continue reading

Lost Minneapolis Parks: Oak Lake, Two Ovals and Two Triangles

Another convergence: the season of farmers’ markets is upon us and so is a decision on whether the Minnesota Vikings get a new tax-supported stadium. The site favored for a stadium by some Hennepin County commissioners is the Minneapolis Farmers’ Market on Lyndale Avenue just west of downtown and Target Field.

You’d never know by looking at it today, but the site is rich in history. The current market sits in the middle of what was once Oak Lake, one of the attractions of a semi-exclusive and progressive residential neighborhood late in the 19th Century. It was Minneapolis’s second-oldest park. A bandstand near the lake was built in 1881 to host some of the earliest outdoor concerts in the city. The gracefully curved streets of the neighborhood filled with the carriages of wealthier concert goers, while residents of the neighborhood and music lovers without carriages sat on the sloping hillside in what was called a natural amphitheater near the lake.

Oak Lake Addition, platted in 1873. 1892 plat map (John R. Borchert Map Library, University of Minnesota)

Some people say the Oak Lake Addition experienced gentile flight, then white flight, as the neighborhood went from mostly white Protestant to Jewish to black before it finally gave way to industrial and market uses. And it happened fast. But the trendy little neighborhood was probably doomed by something much more benign than ethnic, religious or racial bigotry; the creation of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners helped kill the Oak Lake Addition.

More on Murphy Square and Augsburg College — and more praise for the Minnesota Historical Society.

In response to my request for info on Murphy Square before the freeway, Juventino Meza, a student at Augsburg College, reports that two books provide stories and photos of the Augsburg campus and the neighborhood before the 1960s. He writes that From Fjord to Freeway: 100 Years of Augsburg College, by Carl H. Chrislock, is available at the Augsburg library. He also recommends From Immigrant Parish to Inner-city Ministry: Trinity Lutheran Congregation 1868-1998, by James S. Hamre. The Trinity Lutheran Church building, once located south of Murphy Square and the Augsburg campus, was taken out by the freeway. The latter book is available from Trinity Lutheran Congregation, which still exists and has an office at 2001 Riverside Avenue and a website here.

I have written often of the amazing resource this state maintains in the Minnesota Historical Society. More than once I have noted that regardless of subject, I always check to see if the Visual Resources Database at MHS has a photo. While looking for photos of Augsburg College and Murphy Square I was astonished to find a photo of Augsburg history professor Carl H. Chrislock, author of the Augsburg history Mr. Meza recommended. Here’s proof.

Carl H. Chrislock, professor emeritus, Augsburg College, 1970 (Alan Ominsky, Minnesota Historical Society)

Thanks to Mr. Meza——and to Minnesota legislators for the Minnesota Historical Society. It’s probably a good idea to remind your legislators that the Minnesota Historical Society needs their support.

David C. Smith

Has the Park Board Neglected Northeast Minneapolis?

The argument is sometimes made, particularly by “Nordeasters,” that northeast Minneapolis is park poor and that the Minneapolis park board has neglected that part of the city. “Underserved” seems to be the popular word. The idea even flowed as an undercurrent through the recent Minneapolis Riverfront Design Competition. The thinking goes that ever since Minneapolis and St. Anthony merged in 1872, and took the name Minneapolis, power, money and prestige—not to mention amenities such as parks—have accumulated west and south of the river. (Read Lucille M. Kane, The Waterfall That Built a City, for a fascinating examination of why that might have happened.)

While writing recently about Alice Dietz and the marvelous programs she ran at the Logan Park field house I thought again about the perceived neglect of Northeast and whether it might be true. I concluded that it is not; northeast Minneapolis has been a victim of industry, topography and opportunity, but not discrimination or even indifference. What’s more, all those elements have now realigned, putting northeast Minneapolis in the position to get a far bigger slice of the park pie in the foreseeable future than any other section of the city.

Minneapolis Park Hero: Maude Armatage

Dan Greenwood recently produced a report on KFAI radio about Maude Armatage, the first woman on the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners. Armatage, for whom a park and school in south Minneapolis are named, served on the park board from 1921 until 1951, the longest continuous service on the board in its history. (Francis Gross, nicknamed “Mr. Park Board,” served more years, but his service was divided into several terms.) I appreciated the opportunity to tell Dan and his listeners some of what I know about this extraordinary public servant. She is also the namesake of Cafe Maude, a popular cafe near the park and school on Penn Avenue South.

I hope to write more about Armatage and her role on the park board in the near future. Until then, read this very informative article by Caitlin Pine, which originally appeared in the Southwest Journal in 2003, I believe, and has since been reprinted.

David C. Smith

Keep Your Thomas Lowrys Straight

Just to be clear: the Thomas Lowry Memorial is not in Thomas Lowry Park. Neither is it in Lowry Place. (See February 25 post: Lost Minneapolis Parks: Virginia Triangle.)

The Thomas Lowry Memorial, with his statue, was originally erected in 1915 on Virginia Triangle across Hennepin Avenue and a bit south from Thomas Lowry’s mansion on Lowry Hill. Thomas Lowry’s mansion was eventually purchased by Thomas Walker who then created the Walker Art Center on the site.

Thomas Lowry’s home in 1886 looking north over what is now The Parade and the Sculpture Garden. (Minnesota Historical Society)

When Virginia Triangle was erased in 1967 by freeway plans, Thomas Lowry’s statue was not moved to Thomas Lowry Park, because it didn’t exist yet, at least by that name. And it wasn’t moved to Lowry Place, also called Lowry Triangle, another lost park property, because it had already ceased to exist. Virginia Triangle was where northbound Lyndale and Hennepin avenues met at Groveland; Lowry Place was where they parted again at Vineland and Oak Grove.

Lowry Triangle is on the immediate left as you look north on Hennepin Avenue toward the Basilica. Oak Grove Street and Loring Park are on the right. Vineland Avenue, leading to the Walker Art Center, is on the left. Virginia Triangle and Thomas Lowry’s Memorial are directly behind you in 1956. (Norton and Peel, Minnesota Historical Society)

Lowry Triangle, officially named Lowry Place on May 15, 1893, was acquired by the park board from the city in 1892. The park board asked the city to hand over the triangle on November 2, 1891. It was slightly smaller than Virginia Triangle to the south. Lowry Place was at one time intended to be the home of the statue of Ole Bull that in 1897 ended up in Loring Park. Park board president William Folwell wrote to Thomas Lowry to ask if he objected to Ole Bull’s statue being placed across Lyndale Avenue from Lowry’s house on a park property that bore his name. Lowry replied that he appreciated the courtesy of being asked and had no objection. I don’t know why the statue was then placed in Loring Park instead. If you do, please tell. That’s not all I don’t know: I also don’t know why Lowry’s memorial was placed originally on Virginia Triangle instead of Lowry Triangle.

By the time the Lowry Memorial had to be moved in 1967 it was too late to shift it to the Lowry Triangle; that little patch of ground (0.16 acres) had already been acquired by the State of Minnesota in 1964 in anticipation of reconfiguring streets for the construction of I-94.

Moving the memorial to Thomas Lowry Park wasn’t an option then because at that time what is now Thomas Lowry Park at Douglas Avenue, Bryant and Mt. Curve was named Mt. Curve Triangles. That isn’t a typo, it was officially named Mt. Curve Triangles, plural, in November 1925 when its name was changed from Douglas Triangle. That was perhaps done to distinguish it from Mt. Curve Triangle, singular, which had been the name of a tiny street triangle at Fremont and Mt. Curve since 1896. That triangle was renamed Fremont Triangle in 1925, when the Mt. Curve name was shifted a few blocks east to Douglas Triangle. Mt. Curve Triangles was nearly 1.5 acres while Fremont Triangle was only .02 acre.

Thomas Lowry Park in 1925 when it was still Douglas Triangle, before it became Mt. Curve Triangles. You can find other images of the property at the Minnesota Historical Society’s Visual Resources Database, but only if you search for Douglas Triangle or Mt. Curve Triangle, not Thomas Lowry Park. (Hibbard Studio, Minnesota Historical Society)

To confuse matters, the popular name for the property was neither Douglas Triangle, nor Mt. Curve Triangles, nor Thomas Lowry Park, but “Seven Pools” after the number of artificial pools designed for the park by park commissioner and landscape architect Phelps Wyman in 1923.

Thomas Lowry and his name had nothing to do with Mt. Curve Triangles, other than the fact it was located on Lowry Hill near his old mansion, until residents in the neighborhood campaigned to have the park renamed for Lowry in 1984. (Lowry did ask the park board to improve and maintain the land in 1899, but his request was refused because the park board didn’t own the land then. It didn’t purchase the land until 1923.)

Given that there was no other place named Lowry to put the memorial to Thomas Lowry the park board chose Smith Triangle at Hennepin and 24th. That’s where it still is. The only connection between Smith and Lowry is that they probably knew each other.

Of course neither the Lowry Memorial nor Lowry Park are anywhere near Lowry Avenue, which is miles away in north and northeast Minneapolis. Lowry Avenue is much closer to the former site in Northeast Minneapolis of the Lowry School, which no longer exists either. Lowry School figured prominently in plans for Audubon Park in the 1910s. When Lowry School was built in 1915, Buchanan Street between the school and Audubon Park was vacated with the idea that the park would serve as the playground for the school.

Thomas Lowry School in 1916 showing Buchanan Street vacated between the school and Audubon Park at left. (Minneapolis Public Schools)

Those plans were never formalized. While the park provided space, it didn’t provide play facilities. Playground facilities weren’t developed at Audubon Park until the late 1950s. By that time Lowry School was already outdated and destined for closure. (For more photos of Lowry School click here.)

You can learn more about all of these park properties and how they were acquired, developed and named at the web site of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Elusive Minneapolis Ski Jumps: Keegan’s Lake, Mount Pilgrim and Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park

The Norwegians of Minneapolis had greater success getting their music recognized in a Minneapolis park than they did their sport. A statue of violinist and composer Ole Bull was erected in Loring Park in 1897.

This statue of Norwegian violinist and composer Ole Bull was placed in Loring Park in 1897, shown here about 1900 (Minnesota Historical Society)

A ski jump was located in a Minneapolis park only when the park board expanded Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park in 1909 by buying the land on which a ski jump had already been built by a private skiing club. The photo and caption below are as they appear in the annual report of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners for 1911.* While the park board included these photos in its annual report, they are a bit misleading. Park board records indicate that it didn’t really begin to support skiing in parks until 1920 — 35 years after the first ski clubs were created in the city.

Minneapolis, the American city with the largest population of Scandinavians, was not a leader in adopting or promoting the ski running and ski jumping that originated in that part of the world. Skiing had been around for millenia, but it had been transformed into sport only in the mid-1800s, around the time Minneapolis was founded. Ski competitions then included only cross-country skiing, often called ski running, and ski jumping — the Nordic combined of today’s Winter Olympics. Alpine or downhill skiing didn’t become a sport until the 1900s. Even the first Winter Olympics at Chamonix, France in 1924 included only Nordic events and — duh! — Norway won 11 of 12 gold medals.

The first mention of skiing in Minneapolis I can find is a brief article in the Minneapolis Tribune of February 4, 1886 about a Minneapolis Ski Club, which, the paper claimed, had been organized by “Christian Ilstrup two years ago.” That article said the club “is still flourishing.” Eight days later the Tribune noted that the Scandinavian Turn and Ski Club was holding its final meeting of the year. The two clubs may have been the same.

Ilstrup was one of the organizers two years later of one of the first skiing competitions recorded in Minneapolis, which was described by the Tribune, January 29, 1888, in glowing and self-congratulatory terms.

Tomorrow will witness the greatest ski contest that ever took place in this country. For several years our Norwegian cultivators of the noble ski-sport have worked assiduously to introduce their favorite sport in this country, but their efforts although crowned with success, did not experience a real boom until the Tribune interested itself in the matter and gave the boys a lift.

The Tribune mentioned the participation in the competition of the Norwegian Turn and Ski Club, “Vikings club” and “Der Norske Twin Forening.” The Tribune estimated that 3,000 spectators watched the competition held on the back of Kenwood Hill facing the St. Louis Railroad yard. Every tree had a dozen or so men and boys clinging to the branches, while others found that perches on freight cars in the rail yard provided the best vantage point.

The caption for this photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Visual Resource Database claims the photo is from the winter of 1887, but was almost certainly taken at the ski tournament held on Kenwood Hill late that winter in February, 1888.

The competition consisted of skiers taking turns speeding downhill and soaring off a jump or “bump” made of snow on the hill. Points were awarded for distance and for style points from judges.

The winners of the competition were reported as M. Himmelsvedt, St. Croix Falls, whose best jump was 72 feet, and 14-year-old crowd favorite Oscar Arntson, Red Wing, who didn’t jump nearly as far, but jumped three times without falling. Red Wing was a hot bed of ski-jumping, along with Duluth and towns on the Iron Range. (The winner was perhaps Mikkjel Hemmestveit, who along with his brother, Torger, came from Norway to manufacture skis using highly desirable U.S. hickory. The Hemmestveit brothers are usually associated with Red Wing skiing, however, not St. Croix Falls.)

A Rocky Start

Despite the enthusiasm of the Tribune and the crowds, skiing then disappeared from the pages of the Tribune until 1891, when on March 2, the paper reported on a gathering of thirty members of the Minneapolis Ski Club at Prospect (Farview) Park. “This form of amusement is as distinctively Scandinavian as lutefisk, groet, kringles and shingle bread,” the Tribune reported. “With skis on his feet a man can skim swiftly over the soft snow in level places, and when a slope is convenient the sport resembles coasting in a wildly exhilarating and exciting form,” the report continued. The article also described the practice of building snow jumps on the hill, noting that “one or two of the contestants were skilful enough to retain their equilibrium on reaching terra firma again, and slid on to the end of the course, arousing the wildest enthusiasm.”

The enthusiasm didn’t last once again. The Tribune’s next coverage of skiing appeared nearly eight years later — but it came with an explanation:

During recent winters snow has been a rather scarce article. A few flakes, now and then, have made strenuous efforts to organize a storm, but generally the effort has proven a failure. The heavy snow of yesterday was so unusual that it is hardly to be wondered at that there arose in the breasts of local descendants of the Viking race a longing for the old national pastime, skiing…The sport of skiing was fostered to a considerable extent in the Northwest, and particularly in this city, a few years ago, but the snow famine of late winters put a damper on it.

— Minneapolis Tribune, November 11, 1898

The paper further reported that the “storm of yesterday had a revivifying effect upon the number of enthusiasts” and that the persistent Christian Ilstrup of the Minneapolis Ski Club was arranging a skiing outing on the hills near the “Washburn home” (presumably the orphanage at 50th and Nicollet). The paper also reported that while promoters of the club were Norwegian-Americans, “they do not propose to be clannish in the matter.”

Within a week of that first friendly ski, Continue reading

Powderhorn Park Speed Skating Track: Best Ice in the United States

Many years before Frank Zamboni invented his ice resurfacer (in California!?), Minneapolis park board personnel had to prepare the speed skating track at Powderhorn Park mostly by hand for international competition and Olympic trials. They were very good at it.

Olympic medalist speed skater Leo Friesinger from Chicago (whom you already met in these pages here) had this to say after he won the Governor Stassen trophy as the 10,000 Lakes senior men’s champion in the early 1940s:

“It is a pleasure for me to return to Minneapolis and skate on the best ice in the United States.”

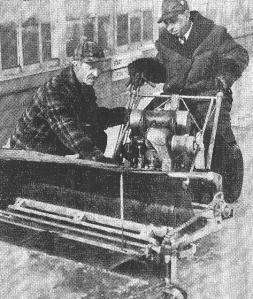

That was high praise for Elmer Anderson and Gotfred Lundgren, the park board employees who maintained the track at Powderhorn using this sweeper, a tractor-drawn ice planer and a bucket of warm water.

The ice sweeper that cleaned the Powderhorn speed skating track in the 1940s. Elmer Anderson (left) and Gotfred Lundgren kept the track in top shape.

They began to prepare the track 3-4 days before a meet by sprinkling it with water a few times. Then they’d pull out a tractor and a plane—a 36-inch blade—to smooth out any bumps from uneven freezing. The biggest problem was cracks in the ice. So the day before the race, Elmer and Gotfred would spend 8-10 hours filling small cracks by pouring warm water into them.

At times their crack-filling work continued right through the races. When large crowds showed up, and for some races attendance surpassed 20,000, the ice tended to crack more often. If Elmer or Gotfred spotted a crack during a race they’d hustle out with a bucket of water after skaters passed and try to patch it. The sweeper was used to remove light snow from the track.

Elmer and Gotfred, who began working for the park board on the same day 18 years before this picture was taken, agreed that the most speed skating records were set when the air temperature was about 30 degrees, which raised a “sweat” on the ice and produced maxiumum speed.

(Source: an undated newspaper clip in a scrapbook kept by Victor Gallant, the park keeper for many years at Kenwood Park, Kenwood Parkway and Bryn Mawr Meadows.)

It’s no wonder that speed skating (as well as hockey) eventually moved indoors to temperature-controlled arenas. But wouldn’t it be fun to see a big race at Powderhorn again?

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Comments (5)

Comments (5)