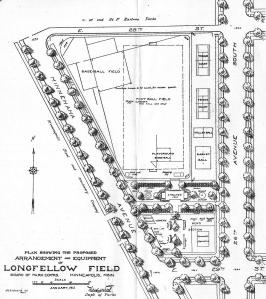

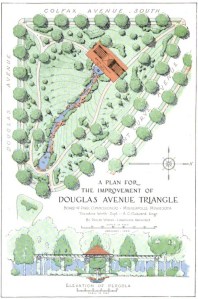

Minneapolis Park Planning: Theodore Wirth as Landscape Architect. Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans, Volume I, 1906-1915

In Theodore Wirth’s 30 years as Minneapolis’s superintendent of parks (1906-1935), he produced annual reports that contained 328 maps, plans or designs for parks and park structures. Most of the plans were accompanied by some explanatory text, which provides a rich record of park board activity and Theodore Wirth’s priorities.

The annual reports include plans for recreation shelters, bridges, parkways, parks, playgrounds, gardens, golf courses, and more. Nearly every Minneapolis park is represented in some form, from if-cost-were-no-object conceptual designs for new parks to the “rearrangement” of existing parks. Many of the plans were never implemented due to cost or other objections; others were considerably modified after input from commissioners and the public.

In many cases over the years, Wirth referred in his written narratives to plans published in prior years that he hoped the board would implement. Sometimes it did, often it didn’t. One of the drawbacks to implementing Wirth’s plans was the method of financing park acquisitions and improvements during much of his tenure as superintendent. The costs of both were often assessed on “benefitted” property, along with real estate tax bills. In other words, the people who lived near a park and received the “benefit” of it—both in enjoyment and increased property values—had to pay the cost, usually through assessments spread over ten years. To be able to assess those costs, however, a majority of property owners had to agree to the assessment, and in many neighborhoods property owners refused to agree until plans were modified considerably to reduce costs.

Phelps Wyman’s plan for what is now Thomas Lowry Park from the 1922 annual report is one of the only colored plans and one of the only plans that wasn’t produced by the park board staff.

Many of the annual report drawings contain a “Designed by” tag, but many do not have any attribution. For those that don’t, it is sometimes unclear who the actual designer was. In many cases it would have been Wirth, but in some cases—the golf courses are notable examples—others would have been responsible for the layouts even though they weren’t credited. William Clark, for instance, is known to have designed the first Minneapolis golf courses, Wirth said so, but only Wirth’s name appears on these plans, not Clark’s.

Also, because these plans were created while Wirth was superintendent does not mean that the idea for each project originated with Wirth. Some of the demands for the parks featured here pre-dated Wirth’s arrival in Minneapolis by decades. Other plans were largely his creation. In most cases, however, Wirth was responsible for implementing those plans.

The majority of the drawings were reproduced on a thin, tissue-like paper that could be folded small enough to be glued into the annual reports. The intent was to publish plans large enough to be readable, but not too bulky. The paper is fragile and easily torn when unfolding; I doubt that many of the plans survive. Even where efforts have been made to preserve and digitize the annual reports, such as by Hathitrust and Google Books, the plans on the translucent sheets are not reproduced. In many cases it would require a large-format scanner to digitize them from the annual reports. Originals do not exist for most of these plans, because they were not working plans.

Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans

I’ve been threatening for some time to do something that probably only the planners at the Minneapolis park board and a few others will appreciate. I’m publishing a complete list of the park plans that appeared in the annual reports of the park board. I’m periodically asked when a certain park was discussed, acquired or planned and I search my list of annual report plans quickly to provide some direction. I hope that by publishing this catalog of park plans I can save other researchers a great deal of time.

Unfortunately I do not have copies or scans of the plans themselves. Neither does the park board. You’ll have to go to the Central Library in downtown Minneapolis to view the original annual reports and see these plans. The Gale Library at the Minnesota Historical Society also has copies of the park board’s annual reports for many years.

I’ve started this catalog with the 1906 annual report, the first year that Theodore Wirth was responsible for producing the report, his first year as superintendent of Minneapolis parks. (Several of H.W.S. Cleveland’s original park designs were reproduced in earlier annual reports. I’ll provide a list of those in the very near future. You may still view the very large originals of many of Cleveland’s plans, by appointment, at the Hennepin History Museum. It’s worth a visit!)

The annual reports of the park board were divided into several parts: a report by the president of the park board, reports by the superintendent and attorney, financial reports, and an inventory of park properties. Most of the plans described here were a part of the superintendent’s report. For that reason, I’ve cited the date on Wirth’s reports rather than the date of the president’s report, which at times differed.

I will post the catalog of plans, maps and drawings in three “volumes” due to the size of the file—more than 9,000 words in total. Go to the Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans 1906-1915

Now That’s a Teeter Totter!

I don’t know where or when this photo was taken, but this is how they used to do it in Minneapolis parks. This is how above-average kids used to play. Kid-powered thrill rides provided the adrenaline rush. And there isn’t a single teeter-totter crash helmet in sight — unless that girl has padding in her bow.

I’ve read every Attorney’s Report in park board annual reports, as well as all attorney reports in park board proceedings since 1904, when playground quipment was first installed in Minneapolis parks, and I don’t recall seeing even one report of a lawsuit over injuries on teeter-totters—or any other playground apparatus. Maybe there were no injuries and it was simply the fear of injuries that caused the teeter-totters to be taken down—or scaled down. It’s been years since I’ve seen one. Do they still exist?

Compare this to the two newest playgrounds in Minneapolis parks at Beard Plaisance and William Berry Park near the Lake Harriet Bandstand. Nice, and big improvements, but pretty tame. My favorite playground equipment is still the stuff at Brackett. First they had the Rocket, and now they have innovative equipment that’s quite unlike other parks.

More importantly, how did moms keep those dresses so white?

If you recognize the location above, or can guess the year, please send a note.

David C. Smith

Snowmobiles in Minneapolis Parks: 1967

Do you remember snowmobiles in 1967? I remember them as loud, smelly, uncomfortable and, by today’s standards, horribly unwieldy. Not what you’d expect to find in pristine city parks. But they were very trendy then—the latest and coolest—and Minneapolis parks have always tried to keep up with what was new and in-demand in recreational opportunities. On December 13, 1967 the park board approved establishing a snowmobile course on Meadowbrook Golf Course and renting snowmobiles there.

My snowmobile memories were prompted by the park board’s current interest in allowing snowmobiles on Wirth Lake in Minneapolis as part of a snowmobile convention this winter. I found some 1967 photos of snowmobiles at Meadowbrook a while back and scanned them just because they represented a moment in time for me.

I watched the Vikings Super Bowl IV loss as part of a football/snowmobile party on a farm near Hutchinson in January 1970. (Many farmers in the area were pioneers in snowmobiling, encouraged by the farm implement companies—and their local dealers—that initially invested in the technology. It gave the companies and dealers something to sell year round.) Maybe the Vikings’ embarrassing loss to the Kansas City Chiefs that day tainted my perception of snowmobiles, too; I developed a slight, queasy aversion to them, recalling Hank Stram’s infuriating smirk and bad toupee every time I saw one.

But the snowmobile photos on this page piqued my curiosity for a couple of reasons. One, I couldn’t remember the company “Boatel” or their “Ski-Bird” from my youth. Turns out it was a boat manufacturer in Mora, Minn. that acquired a snowmobile company, the Abe Matthews Company of Hibbing, to broaden its product line. The company apparently manufactured most of the machine, but installed an off-the-shelf engine.

For more information on the Boatel Ski-Birds visit snowmobilemuseum.com and vintage snowmobiles.

The second intriguing aspect of the photo above is the decal on the right front of the machine, “Bird is the word.” In the few photos I’ve found online of the machines — Boatel stopped manufacturing them by 1972 — none of the Ski-Birds have that tagline on them.

If you are of a certain age, or a huge fan of Minneapolis rock-and-roll history, or a Family Guy devotee, you know the line is most famous from a song by The Trashmen in 1963.

Cover photo of Minneapolis surf rockers The Trashmen from their Bird Dance Beat album, their follow-up to Surfin’ Bird. Steve Wahrer (front) was responsible for the raspy vocal on Surfin’ Bird.

The Minneapolis surf-rock band’s Surfin’ Bird, their first record, climbed to #4 on the Billboard Hot 100 and has been covered by numerous groups, from The Ramones to Pee Wee Herman. (See Wahrer performing the song on American Bandstand and being interviewed by Dick Clark. The show wouldn’t pay travel costs for all four band members, so Wahrer performed alone. It must have been odd for him to perform that way because he was the band’s drummer.) It’s a hard song to forget, which was reinforced by its use in a Family Guy episode in 2008 that introduced it to new generations.

I wonder if Boatel bought the rights to the lyric for its Ski-Bird. Surfin’ Bird was based on two songs by The Rivingtons and although The Trashmen significantly reworked them, The Rivingtons, a LA vocal group, were given songwriting credit. So if Boatel did pay rights to use the line, The Trashmen probably didn’t collect anything from it.

I don’t know if these are customers renting snowmobiles or park board employees at Meadowbrook Golf Course. (MPRB)

The park board’s 1968 annual report noted that “ski sleds” were rented at “various wintertime locations.” I was surprised to learn from the 1968 annual report that it was also the first year electric golf carts were used on any Minneapolis park golf course; they were also first rented at Meadowbrook. So snowmobiles beat golf carts onto park board golf courses by a few months. The contract for 13 snowmobiles and 6 snowmobile sleds for rental was won by the Elmer N. Olson Company.

Golf carts and snowmobiles weren’t the only attractions added to parks in 1968 in hopes of generating new revenue. Pedal boats were added to Loring Lake, an electric tow rope was installed in the Theodore Wirth Park ski area, and construction began on a miniature sternwheeler paddle boat to carry 35-40 passengers at a time on rides through Cedar Lake, Lake of the Isles, and Lake Calhoun.

A constant in the 129-year history of the Minneapolis park board has been the search for new revenues to support an expensive park system. If given a choice between snowmobiles in the city and good food at well-run restaurants in parks, such as now exist in three locations and will be joined by a new food service at Lake Nokomis next year, I’d chose the food. Blame the Kansas City Chiefs.

I haven’t found any record of rental rates for the snowmobiles the first year, but in January 1969 the park board approved a rental rate of $3.64 per 1/2 hour (plus 3% sales tax!) for park board snowmobiles and a charge of $1.25/hour or $3.75/day for the use of private snowmobiles on the Meadowbrook course.

I wonder if the Meadowbrook greenskeeper liked snowmobiles on the course with so little snow. (MPRB)

A more contentious issue was a park ordinance passed in early January 1968 that permitted, but regulated, the use of snowmobiles on Minneapolis lakes and parks. By November 1970, before a third snowmobiling season could begin, some residents had apparently had their fill of snowmobiles in the city and the park board considered banning the use of snowmobiles on park property, including the lakes. Park Commissioner Leonard Neiman, who represented southwest Minneapolis, proposed rescinding the ordinance that allowed snowmobiling, which suggests that residents near Lake Harriet and Lake Calhoun might have led the opposition. The board did not vote to eliminate snowmobiling from parks at that time, but it did reduce the speed limit for snowmobiles — from 25 to 20 mph — and added a noise-control provision that mandated mufflers. It also directed staff to consider which parks or lakes snowmobiles would be permitted to use. The decision to lower the speed limit on snowmobiles in parks was credited in 1979 (12/19 Proceedings) with essentially eliminating snowmobile permit applications. None had been received since 1972.

Sometime between 1979 and 2002 the park board made slow snowmobiling even less appealing by setting the price for an annual snowmobile permit at $350. Pokey and pricey wasn’t a big sale. The board voted in 2002 to eliminate snowmobiling permits altogether, because no one had applied for one in many years.

The park board proposes now to charge $1,000 a day for permitting snowmobiles (does that cover multiple machines?) to use Wirth Lake during a convention that MEET Minneapolis estimates will bring $1 million to the city this winter. Sounds like a reasonable trade-off to me — especially because snowmobiles have changed so much since 1970, and so few residences are within earshot of Wirth Lake anyway

Finally, here’s your cocktail party trivia for this week. One of only four survivors of the raft of companies that competed for snowmobile market share in the late 1960s is Bombardier, the Canadian makers of Ski-Doo. The company is now 50% owned by Bain Capital of presidential campaign fame. Of course, two of Ski-Doo’s biggest competitors are Arctic Cat and Polaris, both based in Minnesota.

I wonder if any of the Trashmen ever rented a “Bird is the word” snowmobile at Meadowbrook.

Papa-oom-mow-mow.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

1955 Was a Very Dry Year

It’s not a common sight. I’d never seen it myself until I saw this picture from Fairchild Aerial Surveys taken in 1955. St. Anthony Falls is completely dry.

The concrete apron at St. Anthony Falls is bone dry in 1955. The 3rd Avenue Bridge crosses the photo. Dry land — even a small structure — left (west) of the falls stand where the entrance to the lock is now. (Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Water levels were down everywhere at the time. Meteorological charts list 1955 as the 13th driest year on record in Minneapolis, but a look at longer-term data reveal that rainfall had been below normal for most of the previous 40 years. Downstream from St. Anthony Falls, the river was also very low, revealing the former structure of the locks at the Meeker Island Dam.

The old lock structure from the Meeker Island Dam protrudes from the low water in 1955. The old lock and dam between Franklin Avenue and Lake Street were destroyed when the new “high dam” or Ford dam was built near the mouth of Minnehaha Creek downriver. (Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

That dry spell had a significant impact on park property. Many park board facilities, from beach houses to boat houses and docks, were permanent structures that required proximity to the water’s edge. Parks were also landscaped and mowed to the water line and, since the depression, at least, many lakes had WPA-built shore walls that looked goofy a few feet up on dry land.

Park board annual reports provide time-lapse updates.

1948: Minnehaha Creek dry most of the year, lakes down 1.5 feet.

1949: Chain of Lakes 2 feet below normal, rainfall 2.5 inches below normal, water in Minnehaha for limited time during year

1950: Lake levels at record lows, lake channels dredged 4.5 feet deeper to allow continued use, water in Minnehaha Creek for only brief period in spring

1951: Record snowfall and heavy rains raised lake levels 0.44 feet above normal in April; flooding problems along Minnehaha Creek golf courses required dikes to make courses playable; attendance at Minnehaha Park high all year due to impressive water flow over falls.

1952: Wet early in year, dry late; lake levels stable except those that depend on groundwater runoff, such as Loring Pond and Powderhorn Lake, which were down considerably at end of year

1953: Lake levels fluctuated 1.5 feet from early summer to very dry fall; flow in Minnehaha Creek stopped in November; U.S. Geological Survey began testing water flow in Bassett’s Creek for possible diversion

1954: Again, water level fluctuations; near normal in early summer, low in fall; Minnehaha Creek again dry in November.

1955: Fall Chain of Lakes elevation lowest since 1932, but Lake Harriet near historical normal; Minnehaha dry most of year

1956: Lakes 4 feet below normal, weed control required, boat rentals incurred $10,000 loss

1957: City water — purchased at a discount! — pumped into lakes raised lake levels 1.5 feet; park board began construction of $210,000 pipeline from Bassett’s Creek, which, unlike Minnehaha Creek, had never been completely dry, to Brownie Lake.

1958: Second driest year on record; Minnehaha Creek dry second half of year; pumps activated on pipeline from Bassett’s Creek, raised water level in lakes 4.2 inches by pumping 84,000,000 gallons of water.

1959: Dry weather continued; Park board suggested reduction in water table may be result of development; Park board won a lawsuit against Minikahda Club for pumping water from Lake Calhoun to water golf course. When Minikahda donated lake shore to park board for West Calhoun Parkway in 1908 it retained water rights, but a judge ruled the club couldn’t exercise those rights unless lake level was at a certain height — higher than the lake was at that time — except in emergencies when it could water the greens only. Lakes were treated with sodium arsenite to prevent weed growth in shallower water; low water permitted park crews to clean exposed shorelines of debris.

1960: Lake levels up 4 feet due to pumping and rain fall; channels between lakes opened for first time in two years; hydrologist Adolph Meyer hired to devise a permanent solution to low water levels.

To celebrate the rise in water levels sufficient to make the channels between the lakes navigable after being closed for a couple of years, park superintendent Howard Moore helped launch a canoe in the channel between Lake of the Isles (in background) and Lake Calhoun in 1960. He seems not to mind that one foot is in the drink. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

That’s more than a decade’s worth of weather reports. The recommendation of hydrologist Adolph Meyer was very creative: collect and recycle water from the air-conditioners in downtown office buildings and stores, and pump it to the lakes. That seemed like a good idea until the people who ran all those air-conditioners downtown thought about it and realized they could recycle all that water themselves through their own air-conditioners and save a lot of money on water bills. End of good idea. Instead the park board extended its Chain of Lakes pumping pipeline from Bassett’s Creek all the way to the Mississippi River. But that’s a story for another time.

If you’ve followed the extensive shoreline construction at Lake of the Isles over the last many years, you know that water levels in city lakes remains an important, and costly, issue—and it probably always will be. It’s the price we pay for our city’s water-based beauty.

David C. Smith

Afterthought: The lowest I ever remember seeing the river was following the collapse of the I-35W bridge. The river was lowered above the Ford Dam to facilitate recovery of wreckage from that tragedy. Following a suggestion from Friends of the Mississippi River, my Dad and I took a few heavy-duty trash bags down to the river bank near the site of the Meeker Island Dam to pick up trash exposed by the lower water levels. Even then the water level wasn’t as low as in the Fairchild photos.

The Statue of Liberty in a Minneapolis Park?

If you could put a replica of this statue anywhere in a Minneapolis park, where would you put it?

If you could put a replica of this statue anywhere in a Minneapolis park, where would you put it?

One of the most intriguing “might-have-beens” in Minneapolis park history was the proposed construction of a Japanese Temple on an island in Lake of the Isles. (If you missed it, read the story of John Bradstreet’s proposal.) But that was not the only proposal to spruce up an island in a Minneapolis park.

On March 15, 1961 the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners approved the placement of a replica of the Statue of Liberty on an island in another body of water.

Park board proceedings attribute the proposal to a Mr. Iner Johnson. He offered to donate and install the 10-foot tall replica statue made of copper and the park board accepted the offer — as long as the park board would incur no expense.

I can find no further information on the proposal or why the plan was never executed — or if it was, what happened to the statue.

The intended location of the statue was the island in … Powderhorn Lake.

Island in Powderhorn Lake from the southeast shore, near the rec center in 2012. The willow gives the impression of an entrance to a green cave. (David C. Smith)

The Minneapolis Morning Tribune of March 16, 1961 reported that Lady Liberty was to be installed for the Aquatennial that summer. Was it? Does anyone remember it? I’ve never seen a picture or read a description.

Another park feature from H.W.S. Cleveland

The man-made island was first proposed in the plan created for Powderhorn Park in 1892 by H. W. S. Cleveland and Son. It is the only Minneapolis park plan that carried that attribution. Horace Cleveland’s son, Ralph, who had been the superintendent of Lakewood Cemetery since 1884, joined his father’s business in 1891 according to a note in Garden and Forest (July 1, 1891).

More on Garden and Forest. Horace Cleveland contributed frequently to the influential weekly horticulture and landscape art magazine through his letters to the editor, Charles Sprague Sargent. Sargent was also the first director of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum. Click on Garden and Forest to learn more about the magazine and its searchable archive. (Thank you, Library of Congress.)

Cleveland’s plan for Powderhorn Park featured a bridge over the lake, about where the north shore is now, and an island. The plan was published in the park board’s 1892 annual report. (Horace W. S. Cleveland, MPRB)

Horace Cleveland was 78 and finding the field work of landscape architecture physically challenging when he and Ralph joined forces to produce a plan for Powderhorn. Only a year later his doctor prohibited him from working further. The Cleveland’s were paid $546 for their work at Powderhorn, but the park board didn’t implement parts of the plan for more than ten years.

Horace Cleveland had been a strong booster for making the lake and surrounding land into a park. Powderhorn Lake had been considered for acquisition as a park from the earliest days of the park board in 1883. However, the park board believed landowners in the vicinity of the lake were asking far too high a price for their land. To learn more of the park’s creation see the park board’s history of Powderhorn Park.

After I wrote that history, I found a transcript of a letter Cleveland had written to the park board (Minneapolis Tribune, July 26, 1885) encouraging the board to acquire about 150 acres from Lake Street to 35th Street between Bloomington and Yale avenues, which was, Cleveland claimed, the watershed for Powderhorn Lake. (I can find no Yale Avenue on maps of that time. Does anyone know what was once Yale Avenue?)

The letter repeated Cleveland’s frequent message about acquiring land for parks before it was developed or became prohibitively expensive. But he also claimed that due to the unique topography around the lake that if it were allowed to be developed it would become a nuisance that would be very costly to clean up.

I’ll quote a couple highlights from his argument for the acquisition of Powderhorn Lake and Park:

I am so deeply impressed with the value and importance of one section…I am impelled to lay before you the reasons …that you will very bitterly regret your failure to secure it if you suffer the present opportunity to escape.

The surrounding region is generally very level and the lake is sunk so deep below this average surface, that its presence is not suspected till the visitor looks down upon it from its abrupt and beautifully rounded banks. The water is pure and transparent and thirty feet deep, and its shape (from which it derives its name) is such as to afford the most favorable opportunity for picturesque development by tasteful planting of its banks…All the most costly work of park construction has already been done by nature.

Cleveland concluded his letter to the park board by writing,

I feel it my duty in return for the bounty you have done in employing me as your professional advisor, to lay before you this statement of my own convictions, and request, in justice to myself, that it may be placed on your records, whatever may be your decision.

On the day Cleveland’s letter was presented to the park board, the board voted not to acquire Powderhorn Lake as a park and Cleveland’s letter was not printed in the proceedings of the park board either. Still the lake and surrounding land—about 60 acres, or 40 percent of what Cleveland had initially recommended—were acquired in 1890-1891 and Cleveland was hired to create a design for the park. Cleveland’s proposed foot bridge over the narrow neck of the lake was not built, even though Theodore Wirth incorporated Cleveland’s bridge into his own plan presented in 1907. However Cleveland’s island was created in the lake in the ensuing years.

In a recap of park work in 1893, park board president Charles Loring noted in his annual report that a “substantial dredge boat was built and equipped and is ready to work” at Powderhorn Lake. “I hope the board will be able to make an appropriation large enough,” he continued, “to keep the apparatus employed all of the next season.”

Loring’s hope was really more of a wish because the depression of 1893 was already having drastic consequences for the Minneapolis economy, property tax revenues and park board budgets. Despite severe cutbacks in spending in 1894, however, the park board devoted about 20% of its $48,000 improvement budget to Powderhorn. Park superintendent William Berry reported that the dredge was active in the lake for 90 days. The result was about 1.7 new acres of land created by dredging and filling along the lake’s marshy shore. In addition, nearly 15,000 cubic yards of earth were moved from near 10th Avenue to fill low areas on the north end of the lake.

An island emerges

The next year, 1895, the island was finally created. The park board spent $10,000, one-third of its dwindling improvement budget, dredging the lake and creating the island. Another 7.3 acres of dry land were created along the lake shore and an island measuring just over one-half acre was created in the southern end of the lake.

An island being created by a dredge in Powderhorn Lake, 1895. Tram tracks were built on a pontoon bridge to carry the dredged material. The photo appeared in the 1895 annual report of the park board. Not a lot of trees around at the time. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

By 1897, the only activity at Powderhorn covered in the annual report was the “raising of the dredge boat,” which had sunk that spring, and watering trees and mowing lawns in the “finished portion” of the park. Two years later, Berry reported that the west side of the park was graded, another nine acres of lawn were seeded and 100 trees and 1600 shrubs were planted to a plan created by noted landscape architect Warren Manning. Horace Cleveland had left Minneapolis in 1896, moving with his son to Chicago, where he died in 1900.

It’s unlikely, due to his age, that Cleveland played any role in the actual creation of the island in Powderhorn Lake in 1895. And credit for the idea of an island may not be due solely to Cleveland either, but also to a coincidence in the creation of Loring (Central) Park in 1884. Cleveland’s original plan for Loring Park did not include an island in the pond then known as Johnson’s Lake. Charles Loring later told the story in his diary entry of June 12, 1884 (Charles Loring Scrapbooks, Minnesota Historical Society),

“In grading the lake in Central [Loring] Park the workmen left a piece in the center which I stopped them from taking out. I wrote Mr. Cleveland that I should be pleased to leave it for a small island. He replied that it would be alright. I only wish I had thought of it earlier so as to have had a larger island.”

The development of the island envisioned by Loring while supervising construction, then approved by Cleveland, proved to be a famous success. (The island no longer exists.) Four years later, on October 3, 1888, Garden and Forest published an article about Central (Loring) Park and concluded a glowing tribute with these words:

When it is considered that artificial lakes and islands are always counted difficult of construction if they are to be invested with any charm of naturalness, the success of this attempt will not be questioned, while the rapidity with which the artist’s idea has grown into an interesting picture is certainly unusual. The park was designed by Mr. H.W.S. Cleveland.

Given such praise, it is not surprising that Cleveland would be willing to try an island from the beginning in Powderhorn Lake. Between the time it was proposed by Cleveland and actually created three years later, decorative islands had also earned a faddish following on the heels of Frederick Law Olmsted’s highly praised island and shore plantings on the grounds of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. One landscape historian wondered whether Olmsted’s creation and treatment of his island in Chicago could have been influenced by his 1886 visit to Minneapolis where he would have seen Loring and Cleveland’s island in Loring Park.

The success of islands in Loring Pond and Powderhorn Lake likely also influenced Theodore Wirth when he proposed creating islands in Lake Nokomis and Lake Hiawatha. Both of those islands were scratched from final plans.

The island in Powderhorn Lake is one of three islands that remain in Minneapolis lakes—and the only one that was man-made. Only two of the four original islands in Lake of the Isles still exist. The two long-gone islands were incorporated into the southwestern shore of the lake when it was dredged and reshaped from 1907 to 1910. The two islands that remain were significantly augmented by fill during that period.

A handful of islands still exist in the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, although many more were flooded when the Ford Dam was built. Another augmented island—Hall’s Island—may be re-created in the near future as part of the RiverFIRST plan for the Scherer site upstream from the Plymouth Avenue bridge.

Although Horace Cleveland died in 1900, when the Minneapolis economy finally boomed again the park board voted in April 1903 to dust off and implement the rest of the 1892 Powderhorn Lake Park plan of H.W.S. Cleveland and Son.

The lake was reduced by about a third in 1925 when the northern arm of the lake was filled. Theodore Wirth, the park superintendent at the time, contended that the lake level had dropped six feet for unknown reasons after his arrival in 1906. The filled portion of the lake was converted into ball fields — a use of park land that was unheard of in Horace Cleveland’s time. The lake that Cleveland estimated at 30 to 40 acres in 1885, when he recommended its acquisition as a park, is now only a little over 11 acres.

The northern arm of Powderhorn Lake was filled in 1925. I wonder if the folks who lived in the apartments on Powderhorn Terrace had their rent reduced when they no longer had lakeshore addresses? (City of Parks, MPRB)

Now about that Statue of Liberty. Does anyone remember it in Powderhorn Lake?

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

A Thank You Note from John J. Pershing

After the park board named a new park and playground in southwest Minneapolis, Pershing Field, December 5, 1922, it received a thank you note from the man it was named for—Gen. John J. Pershing.

A thank-you note from General John J. Pershing to the park board for naming Pershing Field for him. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

I have a low resolution photocopy of the letter, which is in the display case in the commissioners room at park board headquarters, and I sent a scan of it to the two people who were the first to answer a question I posed in a posting earlier this week. But it’s so cool I thought everyone should see it.

One of the people I sent it to, Don Lehnhoff, provided this additional information on the letter—which makes it even cooler.

Thanks, Dave. That is very cool. I couldn’t help noticing the letterhead and, having once been an Army draftee myself, was trying to remember the significance. I was thinking of “General of the Army” (singular) which is a 5-star general … I believe there’s only one of those at any given time, and usually only during wartime. If Wikipedia is to be trusted, the Pershing rank of “General of the Armies” has only been conferred twice in history:

“Pershing is the only person to be promoted in his own lifetime to the highest rank ever held in the United States Army—General of the Armies (a retroactive Congressional edict passed in 1976 promoted George Washington to the same rank but with higher seniority.)” Pershing holds the first United States officer service number (O-1).

That’s pretty serious stuff, and puts him in pretty rarefied company … Pershing and G. Washington. Any way … many thanks for sharing that.

Thank you, Don.

David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: Kenwood Triangle Photo Found

In a striking bit of good fortune, I found myself on an airplane last week with Rick Berglund. When Rick told me where he lived, I asked if he had ever seen a picture of Kenwood Triangle, which I had described in Lost Minneapolis Parks: Part II a few weeks ago. The triangle at the intersection of Penn and Oliver avenues next to Kenwood Park was paved over when Franklin Avenue was diverted slightly north in 1981 after Kenwood School was expanded. Rick told me that an old photo of his home included a view of Kenwood Triangle. He has generously shared a copy of the photo, which was taken in 1919.

Kenwood Triangle at the intersection of Penn and Oliver at Franklin next to Kenwood Park. (Lee Brothers, Rick Berglund.)

It was obviously not a triangle in which the park board invested much time, money or creativity. The overhead wire in the photo was likely for the trolley.

The most interesting revelation from my talk with Rick, however, was that he also has the original landscape designs for his property. The designs were created by Phelps Wyman in 1911. It must have been one of his earliest landscapes in Minneapolis. Wyman was the celebrated designer of Thomas Lowry Park and a Minneapolis park commissioner 1917-1924. (See also his marvelous, never-used plans for the Lyndale-Hennepin Bottleneck, Washburn Fair Oaks and Victory Memorial Drive.)

I suspect that many other photos of Minneapolis landmarks are stored away in files, vaults and boxes around town. If you have some, make copies and send them to us. We’ll post them here with attribution and any details you can provide.

David C. Smith

Mystery Starters at Powderhorn Speed Skating Track

This photo is labelled “Olympic Speed Skating Team.” The only date on it is February 16, 1947. That seems too early to have already selected skaters for the 1948 Olympic team. Can anyone identify the skaters? Local skaters Johnny Werket and Ken Bartholomew represented the U.S. at the 1948 Olympics in St. Moritz and Bartholomew won a silver medal. Gene Sandvig and Pat McNamara represented Minneapolis and the U.S. at the 1952 and 1956 Winter Games. (I posted more about those skaters here.) They might all be in this photo.

Can you identify any of these people — skaters and others — at the speed skating track at Powderhorn Park? (MPRB) (Note 9/18: Reader Tom McGrath has identified the starter and the skaters in a comment below. Thanks, Tom and Brian.)

I don’t know the skaters, but I do recognize the fellow in the dark overcoat next to the starter. Anybody know who that is — and what his job was at the time?

I don’t know the guy with the starter’s pistol, but he looks entirely too jolly to be a regular race official. Seems more like a politician holding a noisemaker, but I can’t name him.

Name them all and you get a free lifetime subscription to minneapolisparkhistory.com. (That’s the lifetime of the website, not you.) Be the first to name the man in the dark coat and I’ll email you a free, low-quality photocopy of Gen. John “Blackjack” Pershing’s letter to the Minneapolis park board in 1923 expressing his appreciation for having a park named for him. (More on that story later.)

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Sibley Field Flattened 1923

Sibley Field was one of the bigger challenges the park board faced when it came to building neighborhood recreation parks. 1923 was a very busy year as the park board developed Sibley Field, Chicago Avenue (Phelps) Field and Nicollet (MLK) Field in south Minneapolis, Folwell Field and Sumner Field in north Minneapolis and Linden Hills Field in southwest. But Sibley may have been the biggest challenge, because all four corners of the park were at different grades. Park superintendent Theodore Wirth wrote afterwards that Sibley was one of the only projects for which costs had been seriously underestimated due to the expense of moving dirt. To create level fields, park board crews used a steam shovel and horse teams to move 68,000 cubic yards of earth.

This is one of my favorite photos of neighborhood park construction. It shows dramatically how much earth had to be moved to create an expanse of level ground suitable for playing fields. I wonder if the home owners who sat near the precipice on 20th Avenue South were ever worried.

As I noted in my profile of Sibley Field on the park board’s website, Wirth wrote in the park board’s 1923 annual report that the “formerly unsightly low land” was brought to an “attractive and serviceable” grade.

Photos like this reinforce my admiration for all the people — from neighborhood residents to city leaders — who envisioned, supported, planned and paid for the parks that have made life in Minneapolis better for many generations.

David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: The Complete List, Part III

This is the third and final installment in a series on “Lost Parks” in Minneapolis. (If you missed them, here are Part I and Part II.) These are park properties that once existed, but did not survive as parks. There is a quiz question at the end of this article. It’s very hard.

St. Anthony Parkway (partial). In 1931, the park board swapped the recently completed portion of St. Anthony Parkway from the southern tip of Gross Golf Course to East Hennepin Avenue for the land on which Ridgway Parkway was built from the golf course to Stinson Parkway. The park board gained 19 acres of land in the deal and the entire cost of constructing Ridgway Parkway was also paid. This story of the parkway “diversion” will be told in greater detail some day. It was controversial. (Read the broad outlines of the diversion of St. Anthony Parkway.) Some people have claimed that the diversion of St. Anthony Parkway is one reason for the “Missing Link” in the Grand Rounds. But that link had gone missing long before the “diversion” and wouldn’t have been found with or without the diversion.

Sheridan Field. University Avenue NE and Twelfth Avenue NE, 1.25 acres. The park board purchased the half-block of land across the street from Sheridan School for $7,000 in 1912. At the park board’s request, Twelfth Avenue was vacated between the school and park. The new playground was provided with a backstop for a baseball field and a warming house for ice-skating, but few other improvements were made. In the early 1920s park superintendent Theodore Wirth urged the park board to either expand the playground or abandon it. He believed the site was too small. It was “inadequate,” he wrote, to provide for the “large attendance (it) constantly attracts.” In the 1924 annual report Wirth presented a plan for the enlargement and development of the park, but that was the last mention of the possibility of expanding the playground. A new, much larger Sheridan School was built on the site in 1932, and the following year the park board granted the school board permission to use the park as a playground for the school, provided that all maintenance and improvements would be the responsibility of the school board. It wasn’t until 1953 that the park board officially abandoned the site. In a land swap with the school board, the park board gave up the under-sized Sheridan Park for the site of the former Trudeau School at Ninth Avenue SE and Fourth Street SE. The park at the Trudeau site became Elwell Field II.

Small Triangle. Royalston Avenue in Oak Lake Addition, 0.01 acre. The triangle was never officially named; it was called “small” because it was. Very small. (See Oak Lake.)

John Pillsbury Snyder and Nelle Stevenson Snyder the day they reached New York after being rescued from the Titanic. (StarTribune and Phillip Weiss Auctions)

Snyder Triangle. Fifth Avenue South and Grant Street, 0.06 acre. Purchased by resolution January 15, 1916 for $4,578. The park board had considered and rejected buying the triangle in 1886. The park was named for Simon P. Snyder, a real estate agent who once owned much of the land in the area. As Patrick Dea pointed out in a comment several months ago, Simon Snyder’s grandson, John Pillsbury Snyder, was a 24-year-old first-class passenger on the maiden voyage of the Titanic in 1912. He and his bride, Nelle Stevenson, were returning from their honeymoon — and survived. The triangle named for his grandfather did not. It was lost to freeway construction for I-35W. A triangle park exists today very near the old location, but it’s not owned by the park board. In 1967 the park board offered to help the state highway department landscape the new triangle between I-35W entrance and exit ramps and 10th Street. The old Snyder Triangle appears to be partly under the Grant Park building on Grant Street. I have not found a record of the price the little triangle fetched.

Stevens Circle. Portland Avenue and 6th Avenue South, 0.06 acre. The small park was named for Col. John Stevens in 1893, but at that time it was named Stevens Place. The name was changed to Stevens Circle on August 1, 1928. From its acquisition in 1885 to 1893 the property was called Portland Avenue Triangle. It is not known if a change in the shape of the park prompted the name change from triangle to place to circle. The park was transferred to the park board from the city council in 1885 according to park inventory lists, although there is no record of the transfer in park board proceedings. The only indication of park board ownership of the triangle was an entry in the expenditures of the park board for 1885 for “Triangle, Portland Avenue and Grant Street” in the amount of $1.50. The triangle became the home of a statue of Col. Stevens in 1911. The circle was given back to the city for traffic purposes in 1935, at which time the statue of Col. Stevens was moved to Minnehaha Park and placed near the Stevens House.

Stinson Boulevard (partial). From East Hennepin to Highway 8. 24 acres. A section of the boulevard was given to the city in 1962 because functionally it was a business thoroughfare, not a parkway. The section given to the city included all of the original land donated for a boulevard by James Stinson et al in 1885. It’s good we still have some Stinson Parkway remaining, because as I explained in the history of Stinson Parkway on the park board’s website, I think Stinson Parkway helped keep alive the plans of Horace Cleveland for a parkway that encircled the city. Without Stinson’s generosity, we might not have the Grand Rounds today.

Svea Triangle. Riverside Avenue and South 8th Street, 0.09 acre. The first mention of the triangle is in the minutes of the park board’s meeting of May 3, 1890 when the board received a request that it improve the triangle. The problem was that the park board didn’t own it. So, on June 27, 1890 the city council voted to turn over the triangle to the park board. The land had been donated to the city in 1883 by Thomas Lowry and William McNair and their wives for park purposes. The triangle was reportedly named on December 27, 1893 to honor Swedish immigrants who had settled in the neighborhood. It had previously been known simply as Riverside Avenue Triangle. The triangle was traded to the city council in 2011 in exchange for a permanent easement between Xerxes Avenue North and the shore of Ryan Lake in the northwestern corner of Minneapolis. The city council requested the exchange when making improvements to Riverside Avenue. Svea Triangle is the most recent park lost.

Vineland Triangle. Vineland Place and Bryant Avenue South, 0.05 acre. Transferred to the park board from the city council, May 10, 1912. The triangle was paved over in a reconfiguration of the street past the Guthrie and Walker entrances in 1973, but remains on the park board’s inventory.

Virginia Triangle. Hennepin, Lyndale and Groveland avenues, 0.167 acre. The triangle was apparently named for the Virginia Apartments adjacent to the triangle. The triangle was traded to the park board by A. W. French and wife on January 1, 1900 in exchange for a piece of land they had originally donated for a parkway along Hennepin Avenue. The triangle was sold in 1966 to the Minnesota Highway Department to accommodate interchanges for I-94. The price tag was $24,300, plus the cost of relocating the Thomas Lowry Monument, which had stood on the triangle since 1915. Read much more about Virginia Triangle and the monument here.

Walton Triangle. No property by this name was ever listed in the park board inventory or Schedule of Parks, but was included in the 1915-1916 proceedings in a schedule of wages for park keepers. Walton Triangle was included with Virginia Triangle, Douglas Triangle and Lowry Triangle and other properties in that neighborhood as the responsibility of one parkkeeper. This mysterious property likely got its name from Edmund Walton, a well-known realtor and developer, who lived on Mount Curve Avenue near where this property must have been located.

This photo from the Brady-Handy Collection at the Library of Congress is almost certainly Eugene Wilson when he was a Congressman from Minnesota 1869-1871. The photo by Matthew Brady is identified only as Hon. [E or M] Wilson, but resembles very closely other images of Wilson.

Other Losses to Freeways and Highways.

In addition to the parks listed above, the following Minneapolis parks were trimmed by construction of freeways:

- I-94: Luxton, Riverside, Murphy Square, Franklin Steele Square, The Parade, Perkins Hill, and North Mississippi, as well as easements for bridges over East and West River Parkway.

- I-35W: Dr. Martin Luther King, Ridgway Parkway, Francis Gross Golf Course. The highway department also acquired an easement from the park board to build a bridge over Minnehaha Creek.

- I-394: Theodore Wirth Park, Bryn Mawr, The Parade

- Hwy 55: Longfellow Gardens

I’ve only included properties that were officially acquired or improved, then later disposed of for some reason. The informal parks and playgrounds in empty lots that existed in many neighborhoods, but were never owned or improved by the park board, are not included. I’ve also left out small pieces of a few parks that were sold for various reasons over the years, other than those taken for highways.

If you can add to or correct this list, please let me know. Do you remember anything about any of these former parks? If you do, please send me a note so we can preserve something of them.

TRIVIA TEST. Here’s the Ph.D.-level park quiz question inspired by one of these entries. Two people had two completely different stretches of parkway named for them. One of those people was St. Anthony. (You could argue the parkways were named for the town, not the man, but this is my quiz.) The first parkway named for St. Anthony is now officially East River Parkway. Later the name was given to the parkway across northeast Minneapolis. Name the other person who had two different parkways named for him. Only one of them still has his name.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Keewaydin Park Before and After — 1928

Like a lot of other people I’m curious to see the new look of Keewaydin Park and School. Construction is underway. It has to be an improvement over what was there a few years ago.

Okay, it was a long time ago. In 1928-29 the park board hauled in 38,600 cubic yards of fill to bring the playing fields up to grade on one side. Clearly the neighbors tried to help by discarding their refuse there, too. The crate says “Morell’s Pride Hams and Bacon.” But that wasn’t enough; the fill kept settling. The park board continued to fill the former swamp in 1930-31. By 1932 the field had been filled sufficiently to be regraded and have tennis courts and a wading pool finished. By 1934 the grounds looked much nicer.

Keewaydin was one of the early collaborative projects between the park and school boards. In the park board’s 1929 annual report it noted that the park had one of the best-equipped shelters for skating and hockey rinks due to the “well-appointed” basement rooms of the school. The doors on the lower level in this photo must have been the entrance to those rooms.

Anybody remember skating there or going to school there when it was new? Does anybody want to take a photo of present construction and email it to me? I forgot to zip over and take one Sunday when I was at Longfellow House.

David C. Smith

Comments (12)

Comments (12)