Archive for the ‘Theodore Wirth’ Tag

The Beginnings of a Garden

One hundred years ago next week, Theodore Wirth made a request of the Minneapolis park board that made possible one of Minneapolis’s most cherry-ished landmarks—and parks. The park superintendent who was known for his passion for gardens—and also for hiring a talented full-time park florist, Louis Boeglin—asked the park board to approve preparing a square of ground next to the Minnesota National Guard Armory for a garden. At least for a summer.

The Society of American Florists and Ornamental Horticulturists (SAFOH) were holding their national convention at the Armory in August 1913. The Armory had been built in 1906 between Kenwood Parkway and Vineland Place adjacent to a park known as The Parade. To the east of the Armory, bordering on Lyndale Avenue, was an empty plot of ground that Thomas Lowry had donated to the park board in 1906. It was that square that Wirth asked for. The park board approved Wirth’s request the day he made it — March 4, 1913 — for the “free use” of the space by SAFOH for “an extensive display of outdoor plants consisting of the best adapted hardy and tender plants that can be used for the decoration of public and private grounds and of plant novelties that are not yet known to many florists.”

The green space to the right of the Armory was the site of the SAFOH Garden. Lyndale Avenue is at right. Kenwood Parkway, which no longer goes through, is at top. Thomas Lowry’s residence is where the Walker Art Center is now. (Atlas of Minneapolis 1914, reflections.mndigital.org)

To prepare for this test garden, the board authorized Wirth to provide the property with “the necessary dressing of good loam,” which the board would pay for from funds allocated for The Parade.

As recently as 1911 Wirth had proposed to use the space for tennis courts, in keeping with the active recreation focus of the park, but those courts were not built. (See plan in 1911 Annual Report.)

The Minneapolis Tribune enthused that the garden would be one of the “most beautiful and extraordinary displays that the city has ever enjoyed.” The Tribune estimated (April 20) that some bulbs to be planted, which began arriving from florists around the country in April, were valued at up to $100 each and, therefore, a guard would be posted at the garden site.

As the dates of the convention approached much was written in local newspapers about the floral display that would inform and entertain 1,500 guests from around the country who would make Minneapolis the “floral capital of the country” for a week (Tribune, August 10, 1913). Private railroad cars were to bring florists from the major eastern cities and so many florists were coming from, or through, Chicago that both the Milwaukee Road and Great Northern had dedicated trains from there solely for convention goers.

The Tribune observed that membership in the Society was “coveted” because there was an “exchange of courtesies” among members, such as the “invaluable service” of a “telegraph order system between cities.” Many of us have used the FTD—originally Florists’ Telegraph Delivery—system, which was created in 1910, only a few years before the Minneapolis convention. The image of Mercury, at left, was first used in 1914.

The garden was such a huge hit—with florists and Minneapolis citizens—that one park commissioner recommended keeping the garden and naming it the Wirth Botanical Garden. Wirth, who was vice president of the national society before the convention, was unanimously elected president of the national organization while it was in session in Minneapolis.

The 1913 garden adjacent to the Armory, looking southwest from the intersection of Lyndale Avenue, coming in from left, and Kenwood Parkway, at right. The photo was taken from the Plaza Hotel between The Parade and Loring Park. The garden is now part of the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. (MPRB)

The park board did support the continuation of the garden the following year and it became a popular attraction for decades, in part because of the labels that identified the plants. But the garden was never named for Wirth. It was referred to as the “Armory Garden” until the Armory was demolished in 1934. At that time the land where the Armory stood was donated to the park board. After that the garden became known as “Kenwood Garden.” Those floral gardens, introduced as a concept 100 years ago next week, unquestionably facilitated the current use of the grounds as quite a different type of garden.

For the rest of the garden’s story, look for a documentary being produced by tpt and the Walker Art Center this spring in celebration of the 25th birthday of the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. It is scheduled to premier in late May.

David C. Smith

NOTE May 30,2013: The tpt documentary can now be viewed here.

© David C. Smith 2013

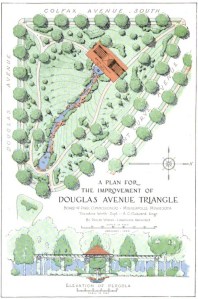

Cleveland’s Van Cleve: A Playground or a Pond

A tantalizing paragraph.

“Professor Cleveland submitted a plan of the improvement of the 2nd Ward Park, whereupon Commissioner Folwell moved that that part of the park designated as a play ground be changed to a pond and that so changed the plan be approved.”

“2nd Ward Park” was later named Van Cleve Park. It was the first park in southeast Minneapolis, not far from the University of Minnesota. I find it odd that the park board would create a pond in a city full of lakes, streams and rivers, but more significant, and unexpected, is what the pond replaced in the plan. A playground. Huh! Horace William Shaler Cleveland, often referred to in Minneapolis by the honorific “Professor,” never seemed a playground sort of guy.

The paragraph appeared in the proceedings of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners from its meeting of May 19, 1890. That date is important because at that time few playgrounds existed. Anywhere.

Before Van Cleve Park was named, it was referred to as 2nd Ward Park as seen here in the 1892 Plat Book for Minneapolis. The man-made pond took the place of what would have been the first “playground” in a Minneapolis park. (C.M. Foote & Co., John R. Borchert Map Library, University of Minnesota)

Unfortunately Cleveland’s drawings for Van Cleve Park didn’t survive. Six of his other park designs—large-scale drawings—are owned by Hennepin History Museum, but the Van Cleve plan is not among them. Neither was it ever published in an annual report, as several other of his plans were. No documents explaining Cleveland’s intent with his plan have been found either, so we really don’t know what type of playground he imagined for the center of the new park. We can only guess.

The Infancy of Playgrounds

The idea of public space devoted to play was still quite new at the time—to Cleveland and to everyone else. In his most famous book, Landscape Architecture as Applied to the Wants of the West, published in 1873, Cleveland mentioned “play ground” only as something that might be desired in the back yard of a home. In his famous 1883 blueprint for Minneapolis’s park system, Suggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolis, he doesn’t mention play or playgrounds at all. Even in the notes that accompanied his first six individual park designs in Minneapolis (unpublished) in 1883 and 1885, he never mentioned play spaces. Yet, in 1890, when he was 76 years old, Cleveland proposed to put a playground in a new park.

The idea was just being explored elsewhere then. In 1886 Boston had placed sand piles for kids play in some parks. The next year San Francisco created a formal children’s play area in Golden Gate Park. In New York, reform mayor Abram Hewitt supported a movement in 1887 to create small, city-sponsored combination parks and playgrounds, but that effort bore little fruit until a decade later. In 1889, Boston created a playstead at Franklin Park and an outdoor gymnasium on the bank of the Charles River, a collaboration of a Harvard professor and Cleveland’s friend Frederick Law Olmsted. Historian Steven A. Riess calls it the “first American effort to provide active play space for slum residents.” (See Riess’s City Games for a fascinating account of the growth of sports in American cities.)

The social reform movement, which later helped create playgrounds in many cities, was gaining steam with the publication in 1890 of Jacob Riis’s, How the Other Half Lives, a glimpse of grinding poverty in the slums of New York. That movement would have an enormous impact on cities in the early 1900s, especially Chicago, which became the playground capital of the United States, led in part by Jane Addams of Hull House settlement fame.

Even though Cleveland addressed many of his efforts in civic improvement to providing fresh air, green spaces and access to nature’s beauty for the urban poor, especially children, he seems an unlikely proponent of playgrounds in parks. Based on the bitter complaint in a letter to William Folwell, July 29, 1884, I had taken Cleveland to be opposed to any manufactured entertainments at the cost of natural beauty. He wrote from Chicago,

“There’s no controlling the objects of men’s worship or the means by which they attain them. A beautiful oak grove was sacrificed just before I left Minneapolis to make room for a baseball club.” (Folwell Papers, Minnesota Historical Society)

Yet, we have proof that Cleveland had a much more positive view of play areas for children in parks than he had of ball fields. A playground at Van Cleve Park, would have been a first in Minneapolis parks.

The Pond Instead

With the revised plan of the park approved, construction of the pond began immediately in the summer of 1890. A pond of 1.5 acres was created in the southern half of the park. The earth removed to create the pond was used to grade the rest of the park. That winter the park board had the pond cleared of snow so it could serve as a skating rink, too.

The artificial pond at Van Cleve was a popular skating rink. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

There must have been problems keeping water in the pond, because the next summer it was drained and the pond basin was lined with puddled clay. An artist’s rendering of the park in the 1891 annual report shows a fountain spraying a geyser of water in the middle of the pond. I’ve never seen a photo of such a fountain at Van Cleve, or read an account of it, but a similar fountain was built into the pond at Elliot Park, the only other pond created in a Minneapolis park, so it is possible a fountain existed. The park board erected a temporary warming house and toilet rooms for skaters on the pond beginning in the winter of 1905.

When Theodore Wirth arrived in Minneapolis as park superintendent in 1906, he placed a priority on improving Van Cleve Park as “half playground, half show park.” He recommended creating a sand bottom for the pond so it could be used as a wading pool and building a small shelter beside it that could double as a warming house for skaters.

The first playground equipment was installed in Van Cleve Park in 1907, following the huge popularity of the first playground equipment installed at Riverside and Logan parks in 1906.

The shelter was finally built in 1910, along with shelters at North Commons and Jackson Square. The Van Cleve shelter was designed by Minneapolis architect Cecil Bayless Chapman and was built at a total cost of just over $6,000. It included a boiler room, toilets and a large central room. The Van Cleve shelter was considerably more modest than the shelters at Jackson Square and North Commons, which cost approximately $12,000 and $16,000 respectively. On the other hand, neither of those parks had a pond. (Jackson Square actually had been a pond at one time, however, called Long John Pond. The cost of the Jackson Square shelter rose due to the need to drive pilings down 26 feet to get through the peat on which the park was built.)

The original recreation shelter at Van Cleve Park was built in 1910 facing the man-made pond. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Wirth published a new plan for Van Cleve Park in the 1911 annual report. Although he claimed that Van Cleve demonstrated that a playground and show park could exist without “interfering” with each other, the playground occupied only a narrow strip of land between the pond and 14th Ave. SE. There were still no playing fields of any kind in the park then.

In 1917, Wirth recommended pouring a concrete bottom for the pond, really converting it into a shallow pool. Two years later the park board did pave the pond basin, but with tar macadam.

The Van Cleve shelter well after 1940 renovations, date unknown. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Very few improvements were made at Van Cleve, or any other park in the city, for many years from the late-1920s to the late- 1940s. In 1935, in his last year as park superintendent, Wirth recommended that a swimming pool be built at Van Cleve in place of the pond, but the park board didn’t have the money for such a project during the Great Depression.

The park did get its share of WPA attention in 1940 when the federal work relief agency completed several renovations on the Van Cleve shelter to improve its capacity to host indoor recreation activities. Also included in those repairs were such basics as a concrete floor in the shelter’s boiler room. Comparing the two photos above, it’s obvious that the veranda was enclosed and the ground around the shelter was paved as well.

The man-made pond was finally filled in 1948. A modern, much smaller concrete wading pool was built to replace it the next year. The little rec shelter stood until a new community center was built at Van Cleve in 1970. By then Van Cleve, like most other neighborhood parks in the city, had been given over almost completely to active playgrounds and athletic fields.

Despite Cleveland’s aborted provision for a playground of some kind in his plan for Van Cleve Park in 1890, I imagine him astonished and a bit saddened to see neighborhood parks change so completely from the pastoral reserves and quiet gardens he had once preserved or coaxed from the urban landscapes of his time.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

The Five Bears

This bear cage was built in Minnehaha Park in 1899 to house four black bears and one “cinnamon” bear. The 1899 report of the Minneapolis park board describes this bear “pit” built for the bears acquired by the park board over the previous few years. The cost of the construction was about $1200. It was built years before the private Longfellow Zoo was operated by Robert “Fish” Jones upstream from Minnehaha Falls. Many people believe, mistakenly, that the zoo in Minnehaha Park was Jones’s zoo. The park board began exhibiting animals in Minnehaha Park in 1894. Jones didn’t open his Longfellow Zoo until 1907, after the park board decided to get rid of most of the animals in its zoo. Jones spotted a lucrative opportunity to expand and profit from his own menagerie in the vacuum created by the park board’s decision.

“Psyche.” That was the brief caption under this photo in the 1899 annual report of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners. I assume it was the bear’s name. Later, the cages held bears named “Mutt,” “Dewey,” and “Chet,” a cub that was a crowd favorite in 1915. Dewey was badly hurt in a fall while trying to catch peanuts thrown from the crowd that year and had to be put down. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

The park board’s 1894 annual report contains the first inkling of what would become a sizable zoo. Superintendent William Berry reported,

“A deer paddock was enclosed, 50 feet square, and shelters built for deer. Two deer were added making a herd of three. Five eagles were presented to the park for which were made a cage covered with heavy wire netting.”

The financial portion of the report noted among maintenance expenditures at Minnehaha Park: Meat for eagles, $15. The next year the park board purchased three elk and accepted gifts of three more deer and three red foxes. For the deer and elk, “a portion of the glen was enclosed with a strong woven wire fence eight feet high, the length of the circuit being 2,950 feet.”

The gifts of animals kept coming and several animals were purchased, too, requiring new accommodations in Minnehaha Park. The 1897 annual report included this information from Berry, “A tank was made and enclosed for the retention of an alligator presented to the Board by the Grand Lodge B. P. O. E.” The alligator had been brought to a national convention of Elks in Minneapolis by the New Orleans delegation and left behind as a gift.

The unusual gift, matched by another free alligator the next year, lead to one of the oddest entries in the financial records of the board over the next few years. Each year the Mendenhall Greenhouse submitted its bill, increasing from $10.50 in 1898 to $14 in 1903, for “Keeping alligators in winter.” A tank in a greenhouse was the only place a warm weather creature could be housed for a Minneapolis winter. Native animals were left outside at Minnehaha, while non-native animals and exotic birds spent the winter in the park board barns at Lyndale Farmstead. Berry noted in 1899 that, “the collection of animals at the barns have proved quite an attraction and a large number of people visit them.”

By then the “collection” had become sizable and the costs had become significant, too. In the 1898 annual report William Folwell wrote,

“A list of animals now owned and kept in the parks is appended. They have been acquired by gift or at slight cost and form an attraction of no small account in the Minnehaha park. The expense of feeding and care has become considerable. A zoological garden is a great ornament to a city and is a most admirable adjunct to school education. The child who can see and study a moose, an eagle, an alligator, or any other strange beast of the field gets what no book can ever teach. It may be proper to continue the present policy, silently developed, of occasional additions to the collections as can be made at slight expense, but the matter ought not to go much further without a definite plan and counting of the cost.”

The list of animals Folwell mentioned shows that it was more than the “petting zoo” that some people think it was:

1 Moose

9 Elk

27 Deer

1 Antelope

4 Black Bears

1 Cinnamon Bear

38 Rabbits

1 Alligator

1 Ape

1 Dwarf Monkey

1 Gray Squirrel

1 Black Squirrel

10 Swans

16 Wild Geese

45 Ducks

1 Mountain Lion

2 Sea Lions

2 Timber Wolves

3 Red Foxes

1 Silver Gray Fox

4 Raccoons

2 Badgers

1 Wild Cat

5 Guinea Pigs

1 Eagle

4 Owls

5 Peacocks

6 Guinea Hens

1 Blue Macaw

1 Red Macaw

2 Cockatoos

It should be noted that not all of the birds lived at Minnehaha park. The swans and some other birds spent their summers at Loring Park. The sea lions and alligator were given new outdoor digs, which included a concrete swimming pool four feet deep, at Minnehaha in the summer of 1899. By then the park board was spending more than $2,000 a year on the care and feeding of its menagerie.

This was all a little too much for landscape architect Warren Manning who was asked to review the entire park system and make his recommendations in 1899. His sensible advice was to get rid of the exotic animals and keep only animals that could live outdoors in “accommodations that will be as nearly like those they find in their native habitat as it is practicable to secure.” Manning was ahead of his time in more than landscape architecture.

It was difficult, however, for the park board to divest a popular attraction. The park board did begin selling excess animals — including several deer to New York’s zoo — but Folwell wrote in the 1901 annual report,

“It is possible that as many people go to Minnehaha park to see the interesting animal collection as to view the historic falls.”

It took the coming of a new park superintendent in 1906 to resolve the issue. Theodore Wirth did not like the animals at Minnehaha, or in his warehouse all winter, and he felt the cramped conditions of some animals was cruel. As was his custom, he minced no words on the subject when he addressed the issue with the park board for the first time on February 5, 1906, barely a month after he took the job as park superintendent. The Minneapolis Tribune quoted Wirth in its February 6, edition:

“The present status of the menagerie is a discredit to the department and the city of Minneapolis…(it is) not only out of place and inharmonious with the surroundings, but to my mind even offensive to the highest degree. I am confident that H. W. S. Cleveland, who through his true artistic love, knowledge and appreciation of nature’s charms and teachings gave such valuable advice and suggestions for the acquirement and preservation of those grounds, would second my opinion in this matter and advise the removal of the menagerie from this spot.”

I’m sure Wirth was right about Cleveland; he would have detested the zoo. Wirth got his wish a little more than a year later when the park board reached agreement with R. F. Jones on his use of land above Minnehaha Falls for his private zoo. Ultimately the park board nearly followed the advice of Warren Manning: it kept the deer and elk in an outdoor enclosure similar to their natural habitat, but it also kept the bears in their pit and cages that didn’t resemble anything natural.

Evicting many of the animals from the zoo did not mean, however, that the park board quit acquiring animals altogether. The next year, 1908, the park board acquired a buffalo, on Wirth’s recommendation, and also acquired more bears. Of course, both animals could survive Minnesota winters outdoors. The hoofed animals remained in the park until 1923. I don’t know when the bear cages were closed or removed. The last information I have on bears in the park comes from the newspaper article in 1915 that reported Dewey’s demise. Theodore Wirth’s plan for the improvement of Minnehaha Glen, published in the park board’s 1918 annual report, still shows the bear pit beside the road to the Falls overlook.

Although the park board sent its exotic animals to R. F. Jones’s zoo in 1907, that was not the last time exotic animals were tenants on park board property. For the winter of 1911 Jones decided not to ship his “oriental and ornamental” animals and birds south for the winter. Instead he kept them in Minneapolis, where he could continue charging admission to see them, I’m sure. He found the perfect spot for such a winter display in the very heart of the city.

Jones rented the Center block at 202 Nicollet on Bridge Square from the park board. The park board had acquired the property for the new Gateway park in 1909-1910, but couldn’t develop the property until tenants leases expired in the buildings it had purchased. As those leases expired, the park board certainly had ample empty space for which a temporary tenant would have been welcome. Jones needed short-term space in a heavily travelled location, and likely got it cheap. The Minneapolis Tribune reported October 22, 1911 that “Mr. Jones thinks that trouble and money can be saved by keeping (the animals) here throughout the entire year.”

A final thought. Minneapolis Tribune columnist Ralph W. Wheelock was more than a little suspicious of R. F. Jones famous story about a sea lion escaping from his zoo down Minnehaha Creek, over the Falls and out to the Mississippi River. This is what he wrote on July 10, 1907, shortly after Jones established his zoo:

“Prof. R. F. Jones, of the New Longfellow Zoo at Minnehaha Falls, announces through the press in a loud tone of voice that he has lost a sea lion. While we would not doubt the word of so eminent a scientific authority, when we recall the clever devices of the up-to-date press agent we think we sea lion elsewhere than in the river.”

This is probably the first story written about Jones in 100 years that did not mention that he wore a top hat and went everywhere with two wolfhounds. He was a colorful character, eccentric entrepreneur and shrewd showman, but he was not the first or only one to run a zoo near Minnehaha Park. The park board beat him to it by 13 years.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Horace Bushnell’s Ghost

Horace Bushnell, one of America’s most influential theologians in the 19th Century, was among the first people to promote parks in Minneapolis. His ghost may still haunt us.

I don’t know if this is really a six-degrees-of-separation story—Bushnell and Kevin Bacon couldn’t have met—but there are quite a number of coincidences involved. They center on the famous Congregational minister from Hartford, Conn. who was also known for his early advocacy of city planning. And I mean really early. 1860s.

I’ll let you do your own research on Horace Bushnell’s sermons and books on theology, but here’s a sample of what he had to say on cities in his book Work and Play; or Literary Varieties in 1864:

The peoples of the old world have their cities built for times gone by, when railroads and gunpowder were unknown. We can have cities for the new age that has come, adapted to its better conditions of use and ornament. So great an advantage ought not to be thrown away. We want therefore a city-planning profession, as truly as an architectural, house-planning profession. Every new village, town, city, ought to be contrived as a work of art, and prepared for the new age of ornament to come.

Horace Bushnell, famous preacher and theologian, encouraged Minneapolis to acquire parkland in 1859-60.

Bushnell expressed an idea well ahead of his time and also coined a phrase: this was one of the first uses of the term “city-planning.”

Of more parochial interest here is Bushnell’s advocacy for creating a park in Minneapolis. More specifically, he was the first to recommend that the towns of St. Anthony and Minneapolis acquire Nicollet Island to be a park. Only Edward Murphy, with his donation to Minneapolis of Murphy Square in 1857, can claim an earlier promotion of parks for the young city.

I only came across the story of Bushnell in Minnesota recently while investigating another subject. Sifting through old newspaper files, I found this comment from “Mr. Chute” (likely Richard, instead of Samuel) at a Minneapolis Board of Trade meeting as reported in the Minneapolis Tribune, February 3, 1874:

“Many of you remember Dr. Horace Bushnell, of Hartford, Conn., who spent a year with us in 1858-59 (sic). He was a gentleman of large heart, if not large means, who, seeing the necessity for a park in Hartford to accommodate the laboring man, whose firm friend he always was, procured and donated the ground to the city for a park, which is now the pride of that wealthy place. When Dr. Bushnell was here his constant burden was, you must secure Nicollet Island; it is a shame and a disgrace to neglect your opportunities; buy it at any price.”

I sought corroboration of Chute’s claim and found it in Isaac Atwater’s History of Minneapolis, Vol. 2. In a profile of Andrew Talcott Hale, the author was explaining that Hale came to Minneapolis from Hartford, Connecticut for his pulmonary health, inspired by the experience of Dr. Bushnell, when he provided this digression:

“While yet Minneapolis was a rural settlement, Dr. Horace Bushnell, of Hartford, Conn., visited it for the benefit of his health, impaired by serious inroads of pulmonary disease. After summering and wintering here, with excursions through out the unsettled prairies of the Dakota, during which he freely contributed by his pulpit ministrations, as well as enthusiastic advocacy of park improvements to the improvement of the morals and culture of the community, he returned to his work in Hartford apparently restored to health and vigor.” (Emphasis added.)

In the mid-1800s, Minneapolis was a destination for many people with pulmonary problems. It was thought that the dry air was a tonic for the lungs. Bushnell’s experience seems to substantiate that belief. He wrote of the Minneapolis climate,

“One who is properly dressed finds the climate much more enjoyable than the amphibious, half-fluid, half-solid, sloppy, grave-like chill of the East.”

Bushnell’s letters to his family, published in The Life and Letters of Horace Bushnell, provide some further descriptions of his life in Minnesota from July 1859 to May 1860. Among my favorite passages is this one on Lake Minnetonka:

“Well, I have talked a long yarn, telling you nothing about the Lake, the strangest compound of bays, promontories, islands and straits ever put together—a perfect maze, in which a stranger would be utterly lost.”

The advantages of Minnesota weather aside, two prominent Minneapolitans—Chute and Atwater—remembered Bushnell’s sojourn in Minnesota and they both recalled his commitment to the idea of parks in cities, Minneapolis included. He had already helped Hartford get one.

Hell without the Fire

The Hartford park referred to by Mr. Chute above was created in 1854 when Bushnell helped convince the residents of that city to approve spending more than $100,000 to purchase forty acres in the center of the city for a public park. That must have taken some doing because it was an abused, polluted tract—”tenements, tanneries and garbage dumps,” according to the Bushnell Park Foundation—that Bushnell himself called, “Hell without the fire.” It is considered the first publicly funded park in the United States.

When Bushnell returned to Hartford from Minneapolis after regaining his health in 1860, little had been done to convert the land into a useful park. So he turned to a friend and former parishioner, who at that time was considered to know something about parks. But Frederick Law Olmsted was occupied with his own park project; he was still working on his most famous creation, Central Park in New York. Pressed for a recommendation, Olmsted suggested landscape architect Jacob Weidenmann for the job.

Weidenmann was an immigrant from Winterthur, Switzerland. (Remember that.) Olmsted later wrote that the only two landscape architects in the U.S. he knew of who were qualified to advise park commissions, other than himself and his partner Calvert Vaux, were Weidenmann and H. W. S. Cleveland. Weidenmann was hired and spent eight years as superintendent of Hartford’s City Park, creating a much less formal park there than was typical in Europe. After Weidenmann’s work was done, Connecticut began building its state capitol adjacent to the park in 1872. It wasn’t until Horace Bushnell was dying in 1876 that Hartford renamed the park in his honor: Bushnell Park. He died two days later.

Meanwhile Samuel Clemens had taken up residence in Hartford in 1871 and had turned to writing fiction. His first novel, The Gilded Age, was co-written with Charles Dudley Warner, who was a Hartford park commissioner.

The Minneapolis Connection

How does this all tie back to Minneapolis? Through Theodore Wirth. As many other cities, including Minneapolis, had caught up to and passed Hartford on the park-o-meter in the 1890s, several of Hartford’s winners in the Gilded Age sweepstakes gave land to the city for parks. Albert Pope left 73 acres to the city for a park in 1894. The same year, Charles Pond left 90 acres of his estate for Elizabeth Park — his wife’s name — and threw in his house and half his fortune to maintain them. Henry Keney went Pope and Pond several hundred acres better that year and donated 533 acres for Keney Park. In 1895 the city purchased another 70 acres for Riverside Park and another 200 acres in the southern part of the city for what became Goodwin Park.

That was a lot of new real estate to whip into park shape. Hartford needed a park superintendent to manage its sudden riches. Hartford’s leaders must have had fond recollections of working with Weidenmann thirty years earlier because when they looked through applicants for the job, they picked someone from the same small town in Switzerland—Winterthur—that Weidenmann had called home. That man was Theodore Wirth.

When Wirth began the job in Hartford, his experience was mostly in horticulture, so Hartford hired Olmsted’s sons—Olmsted Sr. had already retired—as landscape architects for some of the first projects. But after a few years on the job working with the Olmsted firm, Wirth himself designed new park layouts for Elizabeth Park and Colt Park, another 100-plus acre park gift, this from the family famous for revolvers. With those park plans, Wirth established himself as a landscape architect as well as a gardener.

The only Hartford park Wirth did not manage was the enormous Keney Park, which was administered by its own Board of Trustees, separate from the Hartford park commission, and had its own park superintendent, George A. Parker. Wirth and Parker knew each other well. I believe that George Parker was likely responsible for Charles Loring meeting Theodore Wirth in 1905 when he was a committee of one of the Minneapolis park board looking for a replacement for retiring Minneapolis park superintendent William Berry. Parker was the likeliest link between Wirth and Loring because Parker was very active in the new national park organization, American Park and Outdoor Art Association, of which Loring was president 1898-1900. When Loring hired Wirth to become park superintendent in Minneapolis, Parker became the superintendent of all Hartford parks.

Theodore Wirth lived in the upper level of the former Pond house in Elizabeth Park in Hartford, Conn. The ground floor was open to the public. (Picturesque Parks of Hartford, 1900)

The home, at right, in Hartford’s Elizabeth Park also features prominently in an important decision in Minneapolis park history. The reason the Minneapolis park board built a residence for Theodore Wirth at Lyndale Farmstead in 1910 was to fulfill a promise made to Wirth by Charles Loring, when Loring was negotiating terms for Wirth to take the superintendent’s job in Minneapolis. Wirth had been provided housing in Elizabeth Park in Hartford and wanted a similar deal in Minneapolis. Wirth and family had lived in the upper level of the former home of Charles Pond on the estate Pond had bequeathed to the city. The ground floor and verandas of the Pond home were open to the public as shelters in the summer. The Hartford Public Library operated a small library in the building as well.

Elizabeth Park was also the site of Wirth’s earliest claim to fame: the first public rose garden in the United States, a feature he replicated at Lyndale Park near Lake Harriet in 1907.

This turn-of-the-century postcard features one portion of the extensive greenhouses of A. N. Pierson, the “Rose King,” of Cromwell, Conn. about ten miles from Hartford. In 1895 Pierson won the gold medal at the New York Flower Show for a new rose, Killarney, that was beautiful and hardy. He also won 17 firsts and two seconds. “Roses became a profit-making flower, Pierson became the Rose King and Cromwell became Rosetown,” wrote Robert Owen Decker in Cromwell, Connecticut, 1650-1990. A profile of Pierson in American Florist in 1903 speculated, “There are so many rose houses in this establishment that it is doubtful the proprietor knows the exact number.” Pierson started a dairy with 65 cows just to supply sufficient manure for his growing houses. Pierson and Wirth were both vice-presidents of the Connecticut Horticultural Society 1899-1904. I would think it quite likely that Wirth’s very successful public rose garden, established in Elizabeth Park in 1903-4, drew on the cultivating research and expertise of Pierson, too. (Postcard photo: connecticuthistory.com)

Another peculiar connection between Horace Bushnell and Minneapolis parks might be appreciated only by people who have searched for information on the “Father of Minneapolis Parks,” Charles Loring. To begin with, Loring came to Minneapolis the same winter Bushnell was here and for the same reason. Loring had an unspecified health condition—likely a pulmonary malady—that caused him to come west from his Maine home. He tried Chicago first, then Milwaukee, and finally arrived in Minneapolis in the winter of 1860. Although he often spent winters in Riverside, California, he remained a resident of Minneapolis until he died here in 1922.

But an odd link to Bushnell goes further. A young Congregational minister from Hartford, a protege of Bushnell’s, became the founder of the Children’s Aid Society of New York. He publicized widely the plight of children in New York’s slums and, finally, in an attempt to improve the lives of those children he organized what came to be known as “Orphan Trains” that sent New York orphans to better lives, supposedly, with settlers in the west. His name was Charles Loring Brace. Perhaps it is only coincidence that Loring’s rationale for creating parks and playgrounds in Minneapolis was often that children needed places to play and grow.

A final link between Minneapolis and Horace Bushnell’s long visit here. For many years, local historians have turned to a number of late 1800s-early 1900s profiles of Minneapolis that included “vanity” or “subscription” biographies of prominent citizens. One of those, A Half-Century of Minneapolis, was compiled by influential Minneapolis journalist Horace B. Hudson. You’ve probably already guessed the middle name of Mr. Hudson, who was born in 1861, shortly after Dr. Bushnell’s visit here. Yes, his full name is Horace Bushnell Hudson.

More than 150 years have passed since Horace Bushnell implored the people of the little towns on either side of St. Anthony Falls to acquire Nicollet Island as a park. Many attempts have been made, several surveys completed, many speeches delivered in favor and opposed, and part of it acquired, but it’s never become the park Bushnell imagined. Horace Bushnell’s ghost might haunt us until we get it right.

David C Smith

© David C. Smith

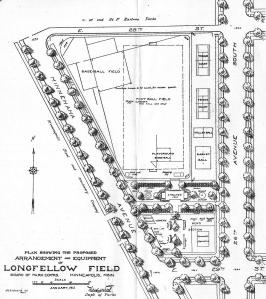

Delineators in Minneapolis Park Plans

When the park board employed its first full-time engineers it’s likely that those engineers also did the drafting or “delineating” of the plans for new parks. The assumption is supported by the attributions on the first plans published in Minneapolis park board annual reports that included someone’s name other than that of Theodore Wirth, who became superintendent of parks in 1906. In the 1908 and 1909 annual reports, the park system’s two engineers, A. C. Godward and W. E. Stoopes, were cited as both engineer and delineator and no other delineators were credited. There may have been none.

Brief biographical sketches of Godward and Stoopes are provided in a previous post on Engineers, so I’ll begin with the first delineator who was never cited as an “engineer” on a park plan. That man was…

I. Kvitrud. I haven’t even discovered his first name. (Note 11/29: Thanks to an anonymous tip, which I’ve confirmed, I learned that Mr. Kvitrud’s first name was Ingwald. Thanks, “T”. For the Google spiders, that’s Ingwald Kvitrud!) Kvitrud was identified as the delineator of three park plans in 1910 and 1912. He was an engineering graduate of the University of Minnesota and served as an officer of the Minnesota Engineering Society in 1910 and 1912. He was hired in 1914 as a full-time instructor in Drawing and Geometry at his alma mater and he was still employed there in 1919, his annual salary having increased in five years from $900 to $1500, according to University records.

The most interesting reference I’ve found to Kvitrud was in an article in the San Francisco Call, July 19, 1913. In a story datelined Minneapolis, Kvitrud was identified as the Minneapolis park board clerk in charge of selling material from the demolition of buildings for a park at The Gateway. Read more

Engineers in Minneapolis Park Plans

I was curious about the people who created the park plans I featured in the Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans, 1906-1935, which was presented in three installments recently (Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3). The catalog identifies all the plans and drawings published in Minneapolis park board annual reports during the tenure of Theodore Wirth as Minneapolis’s park superintendent.

I’ve tried to piece together info on the men whose names appear on those plans as engineers or delineators using park board reports, newspaper archives, and miscellaneous documents found through online searches. I’m not aware of any other background information at the park board on the early engineering and planning staff.

The park board engineering staff about 1915 in their 4th floor offices in City Hall. From left: Alfred C. Godward, Charles E. Doell, Clyde Peterson, Herman Olson, Dick Butler, “Spud” Huxtable, “Spike” Miller and Al Berthe. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

The man whose name appears on almost all of the plans, Theodore Wirth, superintendent of parks, is already well-known. Most of the others, much less so—although two of them, Charles Doell and Harold Lathrop, became very well-known nationally as park administrators.

During that time, the park board employed no “landscape architects.” The profession was still relatively new. The American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) was founded in 1898 and the first university programs in the field were created at Harvard and MIT around the turn of the century. This was after the first generation of true landscape architects in the United States, led by Frederick Law Olmsted and H W. S. Cleveland, had already passed from the scene. Cleveland had been the Minneapolis park board’s advisor and landscape architect from the creation of the park board in 1883, and had helped define the profession in this country. The park board had also hired landscape architect Warren Manning on a few occasions from 1899-1904 to provide advice and park plans after Cleveland retired.

Theodore Wirth was likely hired as park superintendent in Minneapolis in part because he had some experience designing parks in Hartford, Conn. He is credited with the designs of Colt and Elizabeth parks in Hartford. (Early in Wirth’s time in Hartford, the landscape architect role was filled by the Olmsted Brothers, the firm run by the sons of Frederick Law Olmsted. The senior Olmsted was a native of Hartford.) Wirth certainly played the role of landscape architect in Minneapolis, but I’m not aware of him ever calling himself one. He was active in the American Institute of Park Executives, and its predecessor organizations, but never ASLA. For ten years, 1925-1934, Wirth’s name appears on park plans as “Sup’t & Engineer” even though he did not have a formal engineering credential—apart from a course at a technical school in his native Switzerland as a young man. That course may have focused more on gardening than engineering. His first jobs were as a gardener. I could only guess at Wirth’s reasons for taking the “Engineer” title on park plans for the first time at age 62.

During his long tenure in Minneapolis, Wirth built a staff of men with Civil Engineering degrees—all from the University of Minnesota—not landscape architecture degrees or training. The first landscape architect hired full-time by the park board was Felix Dhainin in 1938. (If anyone could tell us more about Dhainin, I’d appreciate it.)

Here’s what I learned about the engineers for the park board 1906-1935. I’ll get to the draftsmen and delineators in a later post. Turns out the most interesting of all the park board engineers wasn’t featured in annual report plans at all! Read on

Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans: Volume III, 1926-1935

The thirty annual reports produced while Theodore Wirth was superintendent of parks in Minneapolis—1906-1935—were rich in detail and illustrations. Those reports included 328 plans, designs and maps of parks and park structures. The publication of those plans usually coincided with the acquisition or development of new properties or the improvement of older ones, so they are a good guide to where to find some discussion of those park properties in annual reports or proceedings. So, long ago I catalogued all of those plans in one document to create a searchable guide to park development during those years. I have relied on that list for the last few years and assumed other researchers and park lovers would find it useful as well. I’ve already posted the first twenty years worth of plans, and today is Volume III, 1926-1935.

Detail of a plan published in the 1912 annual report showing a proposed canoe house on a peninsula in Lake Harriet. (1912 Annual Report, Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners)

The plans published in annual reports were not the only plans created by the park board staff in the years Wirth was superintendent of parks. They are mostly conceptual plans, rather than working plans. The park board requested many of the plans specifically as park commissioners considered various park proposals and possibilities.

The number of employees in the park board’s engineering department are not published in every annual report, but in most years for which that info is provided, it appears that one or two draftsmen were employed. A few of their names appear as “Delineator” or “Del.” on the plans. Sometime in the near future, I’ll provide a guide to some of the names of the people who helped prepare plans.

The titles of the plans are verbatim as they appear on plans. I’ve also copied dates, names and titles as they appear, but have added some punctuation to make them easier to read. Parenthetical comments identify current park names or mention important plan elements.

The annual reports from 1931 to 1935 were not typeset in order to cut costs during the Depression. The reports also contained very few plans or illustrations, not just to reduce printing costs, but because the park board had no money to spend on improving parks. Continue reading

Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans: Volume II, 1916-1925

A few days ago I published the first installment (1906-1915) of a Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans presented in the annual reports of the Minneapolis park board while Theodore Wirth was superintendent of Minneapolis parks (1906-1935). Today I publish the second installment of plans and drawings in annual reports covering 1916-1925.

Along with this “volume” I want to add a dedication and explanation: I am publishing this list of plans for anyone to use, like the rest of the research I have posted here, partly out of my interest in the subject and our civic history. But I also want to acknowledge former park superintendent Jon Gurban’s role in my research. When Jon informed me in early 2007 that I had been selected to write the history of the first 125 years of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board—the book City of Parks was the result—he had one request. He asked that, in addition to writing the book, I would share with park board staff and him other useful, important and interesting information that I uncovered in my research. While conducting research just to write my book proposal that winter, I had found several items that I had brought to his attention that I thought were fascinating. He said that my enthusiasm for those finds and my willingness to share them were factors in me getting the assignment.

So this Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans is published with a nod to Jon Gurban, in my experience an honorable man treated dishonorably by some with whom he shared a passion for Minneapolis parks.

This plan for the Minnehaha Stone Quarry from the 1919 annual report is representative of the plans listed below. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Remember that many of the plans presented in annual reports were conceptual plans and many were not implemented or were revised extensively. Most of the plans were created by park superintendent Theodore Wirth, with exceptions as noted. It would be a mistake, however, to assume because Wirth created the plans that the ideas for the parks also came from him. Some of the plans grew from Wirth’s own vision, while many other plans were requested by the park board or were concepts that had been bouncing around for some years.

This catalog will be most useful for park planners and historians, but also provides many insights into our park system for casual observers or fans of particular parks. After I publish the last third of the catalog (soon), I’ll provide a bit of information on the various individuals who are credited on these plans—as well as some others who weren’t given credit.

The titles of the plans are verbatim as they appear on plans. I’ve also copied dates, names and titles as they appear, but have added some punctuation to make them easier to read. Parenthetical comments identify current park names or mention important plan elements. /s/ indicates a signature.

A quick explanatory note: 1925 was the first year that Theodore Wirth added “engineer” to his title on park plans. That doesn’t indicate a new credential for Wirth, but the departure of A.C. Godward as the park board’s engineer. Godward had taken the job of Engineer for Minneapolis’s new City Planning Department in June 1922, but continued to supervise engineering at the park board, too. When Godward left the park board completely in 1925, his assistant, A. E. Berthe, kept the title Assistant Engineer and Wirth took the Engineer title himself. Despite Wirth’s praise for Berthe’s work, and Berthe being listed in annual reports as “head” of the engineering department, he remained the Asst Engr to Wirth until 1935, when Berthe was listed as Park Engineer or Civil Engineer and Wirth as General Superintendent.

Minneapolis Park Planning: Theodore Wirth as Landscape Architect. Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans, Volume I, 1906-1915

In Theodore Wirth’s 30 years as Minneapolis’s superintendent of parks (1906-1935), he produced annual reports that contained 328 maps, plans or designs for parks and park structures. Most of the plans were accompanied by some explanatory text, which provides a rich record of park board activity and Theodore Wirth’s priorities.

The annual reports include plans for recreation shelters, bridges, parkways, parks, playgrounds, gardens, golf courses, and more. Nearly every Minneapolis park is represented in some form, from if-cost-were-no-object conceptual designs for new parks to the “rearrangement” of existing parks. Many of the plans were never implemented due to cost or other objections; others were considerably modified after input from commissioners and the public.

In many cases over the years, Wirth referred in his written narratives to plans published in prior years that he hoped the board would implement. Sometimes it did, often it didn’t. One of the drawbacks to implementing Wirth’s plans was the method of financing park acquisitions and improvements during much of his tenure as superintendent. The costs of both were often assessed on “benefitted” property, along with real estate tax bills. In other words, the people who lived near a park and received the “benefit” of it—both in enjoyment and increased property values—had to pay the cost, usually through assessments spread over ten years. To be able to assess those costs, however, a majority of property owners had to agree to the assessment, and in many neighborhoods property owners refused to agree until plans were modified considerably to reduce costs.

Phelps Wyman’s plan for what is now Thomas Lowry Park from the 1922 annual report is one of the only colored plans and one of the only plans that wasn’t produced by the park board staff.

Many of the annual report drawings contain a “Designed by” tag, but many do not have any attribution. For those that don’t, it is sometimes unclear who the actual designer was. In many cases it would have been Wirth, but in some cases—the golf courses are notable examples—others would have been responsible for the layouts even though they weren’t credited. William Clark, for instance, is known to have designed the first Minneapolis golf courses, Wirth said so, but only Wirth’s name appears on these plans, not Clark’s.

Also, because these plans were created while Wirth was superintendent does not mean that the idea for each project originated with Wirth. Some of the demands for the parks featured here pre-dated Wirth’s arrival in Minneapolis by decades. Other plans were largely his creation. In most cases, however, Wirth was responsible for implementing those plans.

The majority of the drawings were reproduced on a thin, tissue-like paper that could be folded small enough to be glued into the annual reports. The intent was to publish plans large enough to be readable, but not too bulky. The paper is fragile and easily torn when unfolding; I doubt that many of the plans survive. Even where efforts have been made to preserve and digitize the annual reports, such as by Hathitrust and Google Books, the plans on the translucent sheets are not reproduced. In many cases it would require a large-format scanner to digitize them from the annual reports. Originals do not exist for most of these plans, because they were not working plans.

Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans

I’ve been threatening for some time to do something that probably only the planners at the Minneapolis park board and a few others will appreciate. I’m publishing a complete list of the park plans that appeared in the annual reports of the park board. I’m periodically asked when a certain park was discussed, acquired or planned and I search my list of annual report plans quickly to provide some direction. I hope that by publishing this catalog of park plans I can save other researchers a great deal of time.

Unfortunately I do not have copies or scans of the plans themselves. Neither does the park board. You’ll have to go to the Central Library in downtown Minneapolis to view the original annual reports and see these plans. The Gale Library at the Minnesota Historical Society also has copies of the park board’s annual reports for many years.

I’ve started this catalog with the 1906 annual report, the first year that Theodore Wirth was responsible for producing the report, his first year as superintendent of Minneapolis parks. (Several of H.W.S. Cleveland’s original park designs were reproduced in earlier annual reports. I’ll provide a list of those in the very near future. You may still view the very large originals of many of Cleveland’s plans, by appointment, at the Hennepin History Museum. It’s worth a visit!)

The annual reports of the park board were divided into several parts: a report by the president of the park board, reports by the superintendent and attorney, financial reports, and an inventory of park properties. Most of the plans described here were a part of the superintendent’s report. For that reason, I’ve cited the date on Wirth’s reports rather than the date of the president’s report, which at times differed.

I will post the catalog of plans, maps and drawings in three “volumes” due to the size of the file—more than 9,000 words in total. Go to the Catalog of Minneapolis Park Plans 1906-1915

Who, Exactly, Were the “Huns”?

Discussions of Minneapolis during World War I in a recent post have pointed to another factor that may have reinforced the willingness of the park board to sell the first Longfellow Field to Minneapolis Steel and Machinery as the company expanded to fulfill military contracts: Theodore Wirth, the superintendent of Minneapolis parks was a German speaker and, based on newspaper accounts from early in his tenure as parks superintendent in Minneapolis, he spoke English with a German accent.

Not only did the president of the park board, Francis Gross, have close ties to German immigrants and descendants as president of the German-American Bank, and, presumably spoke German, based on accounts of his speeches, but the park board’s top administrator, Wirth, who was from Winterthur, Switzerland, only several miles from the German border, also spoke German. Seems suspicious, nein?

Even though Wirth had immigrated to the U.S. thirty years earlier, was not from Germany, and Switzerland was neutral during the war, I don’t know if those distinctions were known or made by most people. Could someone like Wirth have felt pressure to profess or demonstrate his “loyalty” to the U.S.—perhaps by agreeing to the sale of park land to a growing munitions maker?

Remember those were days of loyalty oaths, “Americanization” meetings, and arrests of “enemy aliens.” I recently read that the director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, German-born Karl Muck, was arrested as an enemy alien in Cambridge, Massachusetts in March, 1918. He was accused of nefariously featuring too many German composers in his programs—damn that Beethoven!—and was suspected of using his score markings as a secret code. His claim that he was a naturalized citizen of Switzerland proved true, but didn’t keep him from being locked up in a prison camp in rural Georgia for 17 months. He had been offered a conducting job once by Kaiser Wilhelm. He was kept in prison for ten months after the end of the war that made the world safe for democracy, perhaps to ensure that he wouldn’t detonate a lethal Eroica in a crowded concert hall.

Wirth’s native tongue and the proximity to Germany of his hometown may have had no bearing on his standing in Minneapolis or on park board actions during WWI, but in a world where musicians could be locked up for their taste in fugues, it is not out of the question that it crossed someone’s mind. Especially when you read of speeches like those of former President Theodore Roosevelt on a stop in Minneapolis in October 1918. Minneapolis Tribune reporter George E Akerson wrote on October 8:

Theodore Roosevelt, American’s foremost private citizen, yesterday preached his gospel of thorough-going Americanism, to more than 15,000 persons in Minneapolis. At five different meetings, the former president, exhibiting all of his old time aggressiveness, delivered his message, never missing an opportunity to pillory the “Huns within our gates” along with the “Huns without.”

Theodore Roosevelt addressing more than 5,000 workers at Minneapolis Steel and Machinery, October 7, 1918. As WWI neared its end, Roosevelt urged vigilance against the “Huns within.” His black armband signified that he had lost a son in the war. (Minnesota Historical Society.)

Roosevelt was not referring specifically to Germans as much as to those he perceived as enemies of the U.S government, but that would have been a fine distinction to those reading the lead quoted above. The taint of all Germans, past and present, could easily be inferred. One of Roosevelt’s five speeches in his one-day stop in Minneapolis was at the munitions factory of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery, pictured above.

The derogatory “Hun” to describe Germans was derived from the Huns of Attila fame and equated with “barbarian.” Germans and Huns had little in common historically, but the term was a staple of Allied propaganda during the war. Some older warriors, such as Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, stuck with the term in WWII, but “Krauts” became the more popular alternative.

David C. Smith

Canoe Jam on the Chain of Lakes

The newspaper headline hinted of a sordid affair: “Long Line Waits Grimly in Courthouse Corridor.” Many were so young they should have been in school. Others had skipped work. They stood anxiously in the dim hallway, waiting. News accounts put their numbers at 500 when the clock struck 8:30 that April morning. Many had already been there for hours by then. They prayed they would be among the lucky ones to get permits to store their canoes at the most popular park board docks and on the lower levels of the lakeside canoe racks, so they wouldn’t have to hoist their dripping canoes overhead.

The year was 1912 and nearly 2,000 spaces were available on park board canoe racks and dock slips at Lake of the Isles, Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet. Nearly all of them were needed, which represented a huge increase over the 200 permits issued only two years earlier. The city was canoe crazed.

By contrast, in 2011 the park board rented 485 spaces in canoe racks at all Minneapolis lakes, in addition to 368 sail boat buoys at Calhoun, Harriet and Nokomis.

Canoeing was extremely popular on city lakes, especially after Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun were linked by a canal in 1911, followed by a link to Cedar Lake in 1913. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The demand for canoe racks was so great that park superintendent Theodore Wirth proposed a dramatic change at Lake Harriet at the end of 1912 to accommodate canoeists.

Wirth’s plan (above), presented in the 1912 annual report, would have created a five-acre peninsula in Lake Harriet near Beard Plaisance to accommodate a boat house that would hold 864 canoes. The boat house would have been filled with racks for private canoes, as well as lockers for canoeists to store paddles and gear. The boat house, in Wirth’s words, “would protect the boat owners’ property, and would relieve the shores of the unsightly, vari-colored canoes.”

The board never seriously considered building the boat house and that summer the number of watercraft on Lake Harriet reached 800 canoes and 192 rowboats. Most of the rowboats and about 100 of the canoes were owned and rented out by the park board. Even more crowded conditions prevailed at smaller Lake of the Isles where the park board did not rent watercraft, but issued permits for 475 private canoes and 121 private rowboats.

Rental canoes were piled up on the docks near the pavilion at Lake Harriet ca. 1912. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The park board’s challenge with so many watercraft wasn’t just how to store them, but how to keep order on the lake. An effort to maintain decorum on city lakes began in April 1913 when another year of permits was issued. The park board announced before permits went on sale that because of “considerable agitation about objectionable names” on boats and canoes the year before, permits would not be issued to canoes that bore offensive names.

The previous summer newspapers reported that commissioners had condemned naughty names such as, “Thehelusa,” “Damfino,” “Ilgetu,” “Skwizmtyt,” “Ildaryoo,” “O-U-Q-T,” “What the?,” “Joy Tub,” “Cupid’s Nest,” and “I’d Like to Try It.” The commissioners decided then that such salacious names would not be permitted the next year, even though Theodore Wirth urged the board to take the offending canoes off the water immediately.

When the naming rules were announced the next spring, park board secretary J. A. Ridgway was given absolute power to decide whether a name was acceptable. To begin with he allowed only monograms or proper names, but used his discretion to ban names such as “Yum-Yum” even though that was the name of a character in Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Mikado.” Even proper names could be improper.

Despite the strict naming rules, all but 75 of the park board’s 1400 canoe rack spaces were sold by late April, and practically all remaining spaces were “uppers” scattered around the three lakes.

The crackdown on canoe-naming wasn’t the end of the park board protecting the morals of the city’s youth on the water however. Take a close look at the 1914 photo below by Charles Hibbard from the Minnesota Historical Society’s collection.

The photo shows canoeists listening to a summer concert at the Lake Harriet Pavilion. Notice the width of the typical canoe and how two people could sit cozily side-by-side in the middle of the canoe. Now imagine how easy it would be to drift into the dark, get tangled up with the person next to you and make the canoe a bit tippy. Clearly a safety issue.

The Morning Tribune announced June 28, 1913 that the park board would have no more of such behavior. “The park board decided yesterday afternoon, ” the paper reported, “that misconduct in canoes has become so grave and flagrant that it threatens to throw a shadow upon the lakes as recreation resorts and to bring shame upon the city.”

The solution? A new park ordinance required people of opposite sex over the age of 10 occupying the same section of a canoe to sit facing each other. No more of this side-by-side stuff, sometimes recumbent. According to the paper, park commissioners said the situation had become one of “serious peril to the morals of young people.” Park police were given motorized canoes and flashlights to seek and apprehend offenders.

The need for flashlights became evident after seeing the park police report in the park board’s 1913 annual report. Sergeant-in-Command C. S. Barnard, referring to the ordinance that parks close at midnight, noted a policing success for the year. To get canoeists off the lake by midnight, the police installed a red light on the Lake Harriet boat house that was turned on to alert lake lovers that it was near 11:30 pm, the time canoes had to leave the lake. Barnard reported that the red light “has been a great help in getting canoeists off the lake by 11:30 p.m., but owing to the large number who stay out past that time (emphasis added), I would suggest that the hour be changed to 11 o’clock in order to enable the parks to be cleared by 12 o’clock.”

Indignant protest against the side-by-side seating ban arose immediately. Arthur T. Conley, attorney for the Lake Harriet Canoe Club, suggested that the park board show a little initiative and arrest those whose conduct was immoral rather than cast a slur on “every woman or girl who enters a canoe.” If Conley believed the ordinance was a slur on men and boys as well he didn’t say so, but he did add, “We dislike to hear that we are engaged in a sport which is compared with an immoral occupation and that we are on the lake for immoral purposes.”

In the face of protests, the new ordinance was not vigorously enforced and was repealed before the start of the 1914 canoe season. The Tribune noted in announcing the repeal that “the public did not take kindly to the ordinance last year and boat receipts at Lake Harriet fell off considerably on account of it.”

Despite the repeal of the unpopular ordinance, boating fell off even more in 1914. In the annual report at the close of the year Wirth attributed the decline partly to a terrible storm that passed over Lake Harriet on June 23 resulting in the drowning of three canoeists. Newspapers reported dramatic rescues of several others. By 1915 the number of canoe permits had dropped under 1400 even though canoe racks had been added to Cedar Lake, Glenwood (Wirth) Lake and Camden Pond.

The popularity of canoeing continued to decline. Wirth noted in 1917 that there had been a very perceptible decrease again in the number of private boats and canoes on the lakes. While he attributed that decline partly to unfavorable weather, he also noted the “large number of young men drawn from civil life and occupations to military service” as the United States entered WWI.

There were only six sail boats on city lakes in 1917, and all six were kept on Lake Calhoun. The first year that the park board derived more revenue from renting buoys for sail boats than racks for canoes was not until 1940. From then until now sailing has generated more revenue for the park board than canoeing.

The number of canoe permits leveled off for a while in the 1920s at about 1000 per year, but the canoe craze on the lakes had passed, much as the bicycle craze of the 1890s. During the bicycle craze the park board had built a corral where people could check their bikes while at Lake Harriet. That corral held 800 bicycles. At the peak of the much shorter-lived canoe craze in the 1910s, the park board provided rack space at Lake Harriet for 800 canoes. Popular number. Fortunately, the park board did not build permanent facilities—or a peninsula into Lake Harriet—to accommodate a passing fad.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Letters from Theodore Wirth: Gardener Above All?

The letters Theodore Wirth wrote to his friends during his 1936 around-the-world voyage, which included a quote on the Calhoun Beach Club, reveal little about Minneapolis parks, but quite a bit about the man.

When Wirth retired as Minneapolis park superintendent in 1935—he was forced to retire due to civil service age rules—he travelled with his wife to Hawaii, Samoa—where he visited his son, a U. S. Navy officer—Fiji, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, the Canary Islands, England and on to his boyhood home in Switzerland. Over the course of his travels he wrote ten “general letters” to his friends in Minneapolis. The first was dated December 15, 1935 from a ship sailing from Los Angeles to Honolulu and the last was dated September, 1936 from Winterthur, Switzerland, his home town.

As Wirth explained in General Letter No. 2:

There are so many of you back home that it is of course impossible for me to write to you all. Even if I could do so, it would mean that I would be writing on the same subject time and again. I bargained for a good solution of this problem with Mr. Bossen (his successor as park superintendent) and Miss Merkert (his secretary for many years) before we left home, and I am to write a general letter from time to time, which is to be typed and circulated as may be deemed advisable.

The very method of distributing his letters speaks to his Swiss efficiency, but the content of those letters reveals a good bit about the man as well. Most of his letters are inconsequential newsy travelogues, but I am struck that he was most passionate and enthusiastic about plants on many stops during his voyage.

From his first letter, when he wrote of visiting John McLaren, the famous superintendent of San Francisco parks, he singled out trees for comment. Of California’s Redwood State Park, which McLaren took him to visit, he wrote, “the big Redwood trees are worth a world’s trip to see.” It is the first of many references to the grand and unusual plant life he observed.

Of course he wrote also of parks, commenting on a new park being built in Honolulu, and city planning, noting that Adelaide, Australia was the best-planned city he’d ever seen or heard of. But many of his most detailed observations were about plants.

In New Zealand he makes note of the “elaborately planted” grounds at Lake Rotorua, the “gorgeous tree ferns” towering 50 feet above the undergrowth, even the high yields of New Zealand’s wheat farms.

Of a tour of Sydney’s botanical garden with the curator, he notes a fine specimen of Morton Bay Fig, Ficus Macrophylia with a crown 110 feet in diameter and begonias eight to ten feet tall, concluding “there is no end to what I could report along the lines of plant life here.” He writes that Sydney has much more land set aside for recreation and open space than Minneapolis—Australians are “enthusiastic devotees or every worth while sport”—but it is “sadly lacking” in street tree plantings.

Melbourne is “lavishly decorated with floral displays,” he writes, but he also recounts his travel to see gigantic gum (Eucalyptus) trees six to eight feet in diameter and 150 tall, a “truly majestic sight, not unlike our glorious Redwoods,” and notes that the tuberous begonias at the Fitzgerald Gardens there were the largest he had ever seen.

He writes with special enthusiasm about the bulb nurseries of Holland and how the bulbs were auctioned, mentioning that he had letters of introduction to three bulb-growers from his friend O. J. Olson, a St. Paul florist. He encouraged every florist to visit Holland in May.

Thank you, Sonia Abramson

Copies of the ten letters, 48 pages, Wirth sent to his friends were given to the park board in August 2011 by Ed Abramson. Ed’s aunt, Sonia Abramson, was an employee of the park board, working most of her life in administration. Sonia must have been among those who received copies of the letters after Miss Merkert typed them from Theodore Wirth’s handwritten originals. Ed and his sister-in-law, Cookie Abramson, discovered the letters after his aunt died in 1998 at age 93. Ed recalls that his aunt “loved doing what she did.” “She did a marvelous job for the city and the park board treated her well. It was a win-win,” he said.

Wirth makes two other references to things Minneapolis in his letters — in addition to his Calhoun Beach Club reference.

He provides this account of Pago Pago: “The Pago Pago harbor is not any larger than Lake Calhoun. Imagine the lake surrounded by abruptly-raising, densely wooded mountains from 1,700 to 2,200 feet high—absolutely landlocked—the entrance from the ocean not visible once you are in the harbor.”

He also notes that while sailing from Samoa to Fiji, one morning on deck he was “agreeably surprised” to run into Edward C. Gale, a prominent Minneapolis attorney, son of Samuel Gale and son-in-law of John Pillsbury. They travelled on the same ship until they reached Auckland, New Zealand.

Wirth’s ten letters conclude with a description of parks and playgrounds in Switzerland which suggests where Wirth’s views of parks originated. Among his observations:

“The forests of Switzerland are both the nation’s park and playground in the fullest sense of the word.”

“People flock to the woods singly and in droves to find their recreation.”

“The Swiss people are an exceedingly nature-loving nation — the natural scenic beauty of their homeland makes them so.”

“Playgrounds, as we so properly advocate, build and maintain in the States, are not as essential here in Switzerland.”

“The entire population is more or less self-taught in their practice of exercising, physical culture and body development.”

“Playground activities are managed by the school authorities.”

“Park construction and operation are better known here under the name of “Gardenbau” and the branch of government that has jurisdiction over all pertaining to it is the one of Horticulture.”

These claims tend to corroborate my impression that Wirth never quite understood the American affinity for organized ball games and competitive sports. While many, many neighborhood playgrounds were designed by Wirth, there was nearly always in his layouts a clash between his instinct to create gardens—at least visually pleasing spaces—and his recognition of the popular demand for playing fields.

Theodore Wirth accomplished many things as a park superintendent, but I believe, as these letters suggest, his first love was gardening and horticulture.

David C. Smith

Comments (1)

Comments (1)