Archive for the ‘Minneapolis parks’ Category

Minnesota River Valley National Park?

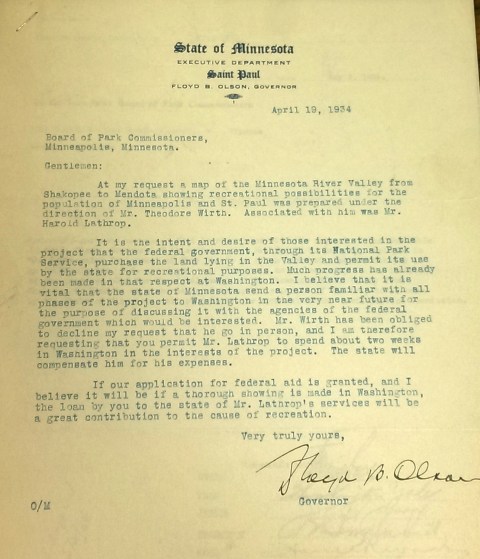

What does the Minnesota River have to do with Minneapolis parks? The Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners, in 1934, tried to help Minnesota Gov. Floyd B. Olson convince the federal government to acquire the Minnesota River valley from Shakopee to Mendota and make it a national park.

I only have the bare bones of the story, but I wanted to throw them out there so someone else could expand it if so inclined. I find this bit of history particularly interesting in light of important efforts by Friends of the Mississippi River and the National Park Service to protect and preserve our rivers. In 1934, Gov. Olson wrote to the Minneapolis park board asking for assistance. I’ve reproduced the letter in full.

Gov. Floyd B. Olson asked the Minneapolis park board for help in creating a national park of the Minnesota River Valley in April 1934.

Always willing to cooperate on park projects, the Minneapolis park board, with Supt. Theodore Wirth’s support, voted on May 2 to give Harold Lathrop, “an employee in the Engineering Department,” leave of absence with pay to go to Washington, D.C. “and spend such time as is necessary in the interest of the proposed plan.”

It’s obvious from Gov. Olson’s letter that he had already secured the assistance of Wirth and Lathrop, and the park board presumably, in creating a map of the “recreational possibilities” of the area. I have never seen such a map created solely for that purpose, but in 1935, the park board published Theodore Wirth’s Tentative Study Plan for the West Section of a Metropolitan Park System. That report contained a detailed map of all of Hennepin County and more, including the closeup below of the Minnesota River Valley. (The full report and map are appended to the park board’s 1935 annual report.)

Detail of park possibilities in the Minnesota River Valley, Shakopee to Mendota, from a 1935 study plan by Theodore Wirth. Harold Lathrop, a park board employee in the engineering department, assisted Wirth on the report. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

I don’t know what became of Gov. Olson’s idea of a national park when Lathrop went off to Washington, D.C. An update came a month later when, at its June 6 meeting, the park board approved Wirth’s recommendation that Lathrop be given two months leave of absence without pay “to act as Project Director for the Federal Government in connection with the proposed Minnesota River Valley development.”

Barbara Sommer writes in Hard Work and A Good Deal that Lathrop was then hired by the National Park Service, which ran the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a federal work-relief program, to supervise CCC work in state parks in Minnesota. There is no indication that any of that work involved a potential park along the Minnesota River. The young National Park Service employee running the CCC program was Conrad Wirth, Theodore’s middle son. Conrad’s performance in that role set him on a trajectory to become the Director of the National Park Service in the 1960s.

I don’t believe Lathrop ever returned to the Minneapolis park board. From his job coordinating federal work in state parks, he was hired as the first director of Minnesota State Parks less than a year later in July 1935. He held Minnesota’s top state parks job until 1946, when he supposedly retired at age 45. Eleven years later, however, he became the first director of state parks in Colorado. Colorado’s first state park is named Lathrop Park.

That’s all I know of the proposed Minnesota River Valley National Park—an intrigue sparked by one letter from the governor in a correspondence file. If you know more, I’d be happy to hear from you.

David C. Smith

P.S. Timely! Friends of the Mississippi River is hosting a fundraiser tomorrow night — October 4—at the Nicollet Island Pavilion in Minneapolis. Suggested donation $100. Worthy cause! Also read the current StarTribune series on threats to the health of the Mississippi.

Burma-Shave, Clinton O’Dell and Minneapolis Parks

Thanks to Lindsey Geyer for sending this picture of Painter Park last week.

The sign at Painter Park, 34th and Lyndale, on September 30, quotes a famous Burma-Shave sign.

Lindsey is probably one of the few people who know the deeper connection between Burma-Shave and Minneapolis parks, especially the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden in Theodore Wirth Park.

Burma-Shave was an invention of a Minneapolis company, Burma-Vita. It was a shaving cream that didn’t require a brush to whip it into a lather and apply. You just rubbed it on with your fingertips. The company president was Clinton O’Dell. He and his sons were looking for a way to market their invention and hit upon the idea of creating signs to post along highways. They painted their advertising on a series of signs and placed them 100 feet apart, a nice distance to read comfortably for people in cars travelling at the dizzying speed of 35 mph.

The O’Dells painted the signs and dug the post holes for them along highways after getting permission from landowners. This was in 1925. The first signs were placed on highways from Minneapolis to Albert Lea and St. Paul to Red Wing. Sales boomed. The signs spread.

In 1940, letterhead of the Burma-Vita Company featured a faint map with a red dot to show the location of every set of Burma-Shave signs the company had placed.

Every dot is a set of Burma-Shave signs in early 1940s, long before interstate freeways. It appears that only five states did not have any Burma-Shave signs. (Enlarged by Lindsey Geyer from Burma-Vita Company letterhead from a letter dated May 6, 1940 to the Minneapolis park board. Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

Sales of Burma-Shave peaked more than a decade later when there were 35,000 Burma-Shave signs. (I haven’t tried to count these dots, but it looks to be considerably shy of 35,000.) They were still being placed along highways into the 1960s, but by then interstate highways and much faster speeds had made the landmark signs a less effective marketing ploy. (Lady Bird Johnson’s Highway Beautification program in the mid-1960s restricted advertising along for federal highways, which had a large impact, too.) The Burma-Shave signs were, however, still a highlight of cross-country car travel in the 1960s. When my family travelled, everyone was roused from whatever they were doing as soon as anyone spotted the first red sign in the distance.

Silly jingles, mostly touting the benefits — often romantic — of a clean shave, were always followed by the Burma-Shave logo. For a catalog of the jingles visit burma-shave.org.

So what does this have to do with Minneapolis parks? When Clinton O’Dell attended Minneapolis Central High School in the 1890s he had a botany teacher named Eloise Butler. Ms.Butler went on to fame as the creator and tender of a fabulous wildflower garden in a portion of what was then Glenwood Park, later renamed Theodore Wirth Park. First as a successful insurance man and later as the owner of Burma-Vita, O’Dell was a significant contributor to the wildflower garden Butler created. For many years he donated money for work in the garden, but in 1944 he donated $3,000 to expand the garden beyond the woodland garden it originally was. An upland or prairie section was added thanks to O’Dell’s generosity. Several years later, in 1951, O’Dell was one of the founders of the Friends of the Wild Flower Garden, an organization that has been critical to the continued success of the garden for more than 60 years. (More info on Friends of the Wild Flower Garden and Clinton O’Dell.)

Thanks to his Burma-Shave fame, O’Dell was named to the Minnesota 150: The People, Places, and Things that Shape Our State, by Kate Roberts, a book by the Minnesota Historical Society Press and an exhibit at the historical society in 2007.

Bottom line: Those catchy Burma-Shave jingles and the ubiquitous red roadside signs were partly responsible for one of the most venerated and beloved patches of Minneapolis park land.

And “Past the school take it slow. Let the little shavers grow” is pretty good advice at any time—even though it had been replaced on the Painter Park sign by Saturday, October 1. In its place was news of a new Zumba class. Fitness is good, too!

David C. Smith

More Lake Nokomis Bath House

In an enjoyable article on Lake Nokomis in MinnPost, Andy Sturdevant provided a link to a couple photos I posted last month of the Nokomis Bath house, so I thought I’d return the favor. I’ve been intending to post this new photo of the bath house I found on a 1920s postcard, so Andy’s article provides a good excuse. I had not seen this photo until a few weeks ago.

Lake Nokomis Bath House in the 1920s. Photographer unknown.

Anyone who knows old cars might be able to date this photo more precisely than I have. Anybody know their early autos? Let us know a likely date range. Based on the age of the trees I would guess it must be very early 1920s.

You can make out the Cedar Avenue bridge in the background. Theodore Wirth wanted to reroute Cedar Avenue around the southwest lagoon shortly after the area was annexed by Minneapolis from Richfield in 1926, but there was too much opposition from property owners in that direction, so we still have that unusual bridge on a county road over a lake.

David C. Smith

The Danger of Danger

It’s popular these days to point out how awful Minneapolitans sometimes were and probably still are. Some writers gleefully discover examples of bigotry in our past and present them almost as badges of honor, “See, we’re really not so nice after all and neither were our grandmas and grandpas.” I don’t know who are more smug, those who find no faults or those who find all faults. Same thing really; an inability to distinguish good from bad. Laziness. The root of all prejudice.

No surprise, we’re flawed. We’ve fixed some of our grandparents’ flaws and I dearly hope our children will fix some of ours. Then it will be up to their children … and so on. Let’s just hope that we don’t backslide.

In the midst of today’s discussions of peace and justice, security and danger, I paused when I came across two letters in a file of documents from the Minneapolis Park Board’s Playground and Entertainment Committee in 1947. This was the committee that, in addition to overseeing playground recreation programs and concerts at bandstands in parks around the city, also issued picnic permits to large groups.

In the early 1900s most of the picnic requests came from church groups, but in the years immediately after World War I, the requests tilted heavily in favor of the newly created veterans groups, mostly American Legion posts, which sponsored neighborhood and charitable picnics in every major park. A bond of brothers perhaps. The only requests for picnics that were refused were from groups that planned to have religious or political speeches. The park board didn’t like partisanship in its parks.

Of the dozens of picnic permit requests filed in 1919 and 1920, the park board rejected only two that I could find: one from a labor union and the other from the Republican Party women’s auxiliary because both planned to have political speeches. When the groups adjusted their programs, they got their permits.

Gradually, however, the park board relented on all counts, even allowing church groups to hold baptisms in city lakes. Labor unions, especially, argued, eventually successfully, that political speech couldn’t be prohibited on public land.

Permits were denied later apparently only because groups were using picnics to raise money that wasn’t going to charities or because of space limitations. That was the issue in July 1947 when the park board got this request from the Twin City Nisei Club. Nisei were second generation Japanese-Americans.

Letter from the Twin City Nisei Club requesting a picnic permit at Minnehaha Park.

The response, written the same day, came from Karl Raymond, the supervisor of recreation. Note that the date was barely a year after the last of the Japanese internment camps had closed in the western United States. Those prison camps had held more than 100,000 Japanese, many American citizens, born and raised in the United States, due to hysteria—absent any evidence of a threat—that any Japanese person, even if raised thoroughly American, was a security risk following Pearl Harbor.

The recreation staff in 1910. One of my heroes of early park history is the man in the suit in the front row, Clifford Booth, the first director of recreation. Karl Raymond, a new hero, is second from right in the second row. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

Karl Raymond had worked for the park board for nearly forty years. He was the supervisor of recreation from 1919 to 1947, when he retired.

In his recommendation to the Playground and Entertainment Committee, Raymond noted that as a general policy the park board did not issue group picnic permits at Minnehaha Park for Saturdays or Sundays, “as the grounds are just about filled up with general use.” But Raymond did not use that excuse. He continued,

“Because of the lateness of the season and the make-up of this group, which includes many veterans of both the Pacific and European sector of the late war, I wish to recommend that this request be granted.”

It was.

It’s worth remembering that the wounds of war were still fresh then. The American death toll had not been 50 or 100 brothers and sisters, but four hundred thousand. It was much easier to recognize a wrong many years later. Forty-one years after this insignificant permission to hold a picnic at Minnehaha Park, President Ronald Reagan signed legislation that acknowledged our nation’s horrible failing, our unwillingness to accept a minority that was different and often misunderstood.

President Ronald Reagan signed legislation that provided for reparations to Japanese Americans who had been imprisoned during Word War II. The bill was sponsored by Alan Simpson, a Republican Senator and Norman Mineta, a Democrat in the House of Representatives. Mineta later became the only Democrat to serve in George W. Bush’s cabinet. (Courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidential Library)

Perhaps I’m a softy, but when I read Karl Raymond’s recommendation to grant a picnic permit, against general policy, I found myself smiling. Way to go, Karl! A little victory for humanity. We can always use more of those—whether you think we’re mostly bad, mostly good or completely woebegone.

Let’s hope we don’t need to find courageous sponsors and signers of legislation forty years from now to correct mistakes we can avoid today.

David C. Smith

©2016 David C. Smith

Lake Nokomis Bath House

One of my favorite pictures of Lake Nokomis. Construction of the bath house was completed in 1920, not long before this photo was taken. The barren landscape — on both sides of the lake — is surprising. (Click the image to enlarge.) This is one of many park board photos that may become available to the public in the near future through the Minnesota Digital Library.

The new playing fields and bath house at Lake Nokomis. Early 1920s. Taken from Cedar Avenue. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

What became of that bath house? The Minneapolis Star ran the photo below on May 2, 1966. The building had been declared unsafe, but demolition was prompted by thousands of dollars of damage done by vandals that winter. Only the toilet rooms of the bath house were left standing for the summer of 1966. A new, smaller bath house was built the next summer. At the time it was the most heavily used beach in the city.

David C. Smith

Arts and Parks: Part II

Another of my favorite recent photo finds is a good intro to my next speaking engagement on Minneapolis park history this Saturday.

I recently found this photo of the Washburn Fair Oaks mansion built by William Washburn in 1883.

Washburn Fair Oaks mansion, probably in the 1880s. Looking west across Third Avenue South in foreground. (W.S. Zinn)

Compare it to this photo taken two Sundays ago from about the same vantage point across Third Avenue South.

Washburn Fair Oaks Park looking west across Third Avenue South.

Now turn about 90 degrees left and you get this image of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Minneapolis Institute of Arts looking southwest across Third Avenue South.

I’ll be talking about both parks and arts, and how many of the same people created Minneapolis’s parks and its art institutions at the Washburn Library on Lyndale Avenue, Saturday, November 21 at 10 a.m. My presentation is being hosted by the Minnesota Independent Scholars’ Forum, but the event is free and open to the public.

For more information visit here. Hope to see you Saturday.

If you want to know more about the landscaping of the Washburn Fair Oaks grounds, you can begin here. Of course, the story features H.W.S. Cleveland.

David C. Smith

The Demise of the 10th Avenue Bridge

In response to the previous post on Charles Tenney’s photos of Highland Avenue and the 10th Avenue Bridge, MaryLynn Pulscher sent her favorite photo of the 10th Avenue Bridge. It’s a fascinating bit of history itself. We don’t know the origin of the photo but believe it’s from a newspaper. If anyone knows who took it or where it was published, please let us know so we can give proper attribution.

David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: Highland Oval

The elegant neighborhood on the hills surrounding Oak Lake—now the site of the Farmer’s Market off Lyndale Avenue—has been gone for decades. Oak Lake itself was filled in 100 years ago. You can read the whole story here. The latest news: I finally found a picture of one of the five small parks in the Oak Lake Addition. I give you Highland Oval.

The title on the photo is “Highland Avenue, Oak Lake Division”, but the open space in the middle of the photo can only be Highland Oval. The view is looking northwest. Tiny, isn’t it? But the effort to preserve any open green space in rapidly expanding cities was a novel concept. (Photo by Charles A. Tenney)

The photo was probably taken in the mid-1880s, before the park board assumed responsibility for the land as a park. The land was designated as park in the 1873 plat of the addition by brothers Samuel and Harlow Gale. Although I have no proof, I believe it likely that H.W.S. Cleveland laid out the Oak Lake Addition, owing largely to the known relationship between Cleveland and Samuel Gale. The curving streets that followed topography and the triangles and ovals at street intersections were hallmarks of Cleveland’s unique work about that same time for William Marshall’s St. Anthony Park in St. Paul and later for William Washburn’s Tangletown section of Minneapolis near Minnehaha Creek. It was also characteristic of Cleveland’s work in other cities.

Photographer Charles A. Tenney published a few series of stereoviews of St. Paul and Minneapolis 1883-1885. He was based in Winona and most of his photos are of the area around that city and across southern Minnesota.

Highland Oval was located in what is now the northeastern corner of the market.

As happy as I was to find the Highland Oval photo, my favorite photo by Tenney tells a different story.

At first glance, this image from Tenney’s Minneapolis Series 1883 was simply the 10th Avenue Bridge below St. Anthony Falls, looking east. The bridge no longer exists, although a pier is still visible in the river. What makes the photo remarkable for me are the forms in the upper left background being built for the construction of the Stone Arch Bridge. (See a closeup of the construction method here.) The Stone Arch Bridge was completed in 1883 — the same year the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners was created.

Nearly 100 years after the bridge was built, trains quit using it and several years later the park board, Hennepin County and Minnesota reached an agreement for the park board to maintain the bridge deck for pedestrians and bicyclists, thus helping to transform Minneapolis’s riverfront—a process that continues today.

Note also the low level of the river around the bridge piers. This was long before dams were built to raise the river level to make it navigable.

David C. Smith

© 2015 David C. Smith

Hiawatha and Minnehaha Do Chicago

The World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago hosted the debut of Minneapolis’s most famous sculptural couple, Hiawatha and Minnehaha, in 1893.

The Minnesota building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 featured Jakob Fjelde’s sculpture of Hiawatha and Minnehaha in the vestibule.

Hiawatha and Minnehaha greeted visitors to the state’s pavilion in their modest plaster costumes nearly two decades before sculptor Jakob Fjelde’s pair took their much-photographed places on the small island above Minnehaha Falls in their bronze finery in 1912.

Hiawatha and Minnehaha in their customary place above Minnehaha Falls. This photo, from a postcard, was probably taken in the 1910s. I chose this picture not only because Hiawatha appears to be climbing a mountain of rocks to cross the stream, unlike today, but also because it is a Lee Bros. photo, the same photographers who shot the photo of Fjelde below.

Jakob Fjelde, Lee Bros., year unknown. I like the cigar. (Photo courtesy of cabinetcardgallery.wordpress.com)

Jakob Fjelde was largely responsible for two other sculptures in Minneapolis parks. He created the statue of Ole Bull, the Norwegian violinist, in Loring Park in 1895. He also created the drawing that Johannes Gelert used after Fjelde’s death to sculpt the figure of pioneer John Stevens, which now stands in Minnehaha Park. Fjelde also created the bust of Henrik Ibsen, Norway’s most famous writer, that adorns Como Park in St. Paul. Fjelde’s best-known work other than Longfellow’s lovers, however, is the charging foot soldier of the 1st Minnesota rushing to his likely death on the battlefield of Gettysburg.

Fjelde’s simple commemoration of the sacrifice of Minnesota men at a pivotal moment in the Civil War. The sculpture was installed in 1893 and dedicated in 1897. (Photo: Wikipedia)

These thoughts and images of sculpture in Minneapolis parks were prompted in part by my recent post on Daniel Chester French, but also by another letter found in the papers of William Watts Folwell at the Minnesota Historical Society. Just two years after Fjelde’s successes with his sculptures for Gettysburg and Chicago, he wrote a poignant letter to Folwell in July 1895 seeking his support for an “extravagant” offer. Fjelde proposes to the Court House Commission, which was developing plans for a new City Hall and Court House, that he create a seven-foot tall statue of the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, John Marshall, and a bronze bust of District Court Judge William Lochren, both for the sum of $1,400. Fjelde calls the price of $1,000 for the Marshall statue “1/3 of its real value.” He explains his offer to Folwell:

“Anyone who knows a little about sculpture work will know that the sums above stated are no price for such a statue but as I for the last six months have been unable to get any work to do at all and have wife and four children to take care of and in spite of utmost economy, unable to make both ends meet, I am obliged to do something extravagant, if only I can get the work to do.”

Fjelde adds that $400 for a bronze bust of Lochren would only pay for the bronze work, meaning that he would be creating the bust free. He writes that he is willing to do so because by getting Lochren’s bust into the Court House, “it might go easier in the future to get the busts of other judges who could afford to give theirs, so I would hope that would give me some work later on.”

He concludes his plea by noting that with his proposition, “The Court House would thereby get a grand courtroom hardly equalled in the U.S.”

Although I have not searched the records diligently, I have not come across anything to suggest that the Court House Commission accepted Fjelde’s offer. That may be because barely two weeks after writing his letter, the Norwegian Singing Society, led by Fjelde’s friend, John Arctander, began to raise money for a statue of Ole Bull. Fjelde began work on that statue in 1895. When all but the finishing touches were completed on the image of the Norwegian maestro the next spring, Fjelde died. He was 37.

I can’t leave another sculpture story without returning a moment to Daniel Chester French. In a longer piece on French a couple of weeks ago, I noted that when his Longfellow Memorial at Minnehaha Falls didn’t materialize, he moved on to create an enormous sculpture for the Chicago World’s Fair. Here it is in its massive splendor. It stood 60 feet tall,

French’s Chicago sculpture was much larger than Fjelde’s, but Fjelde’s sculpture eventually found a home at Minnehaha Falls, where French’s proposed sculpture of Longfellow did not.

David C. Smith

© 2015 David C. Smith

Encore at the Library: The Jewel of Minneapolis

I hope you’ll be able to come to the Minneapolis Central Library on Saturday afternoon, October 3, from 2-3 pm for my encore presentation on how the Mississippi River Gorge in Minneapolis became a park. I first addressed the topic last winter in the Longfellow neighborhood.

Smith – Mississippi River Gorge

I think many people overlook what a spectacular asset has been preserved for our health and enjoyment. So often the emphasis on the Mississippi River in Minneapolis is on reclaiming the river at and above St. Anthony Falls—and that is an exciting development that is overdue—but I think we take for granted the truly unique resource that was preserved for us below the falls. I don’t know that a similar riverfront exists in an urban environment anywhere else in the world. Come and say “thanks!” with me to some people with extraordinary vision and persistence more than 100 years ago.

We would welcome any of our friends across the river in St. Paul to join us, because while my focus is on Minneapolis park history, St. Paul deserves equal credit in preserving the river gorge. As always, there will be plenty of time after my remarks to discuss park and river history.

David C.Smith

Update for Historians and Grammarians

A brief Minneapolis park history update. Essential for Minneapolis historians. Trivial for grammarians.

Grammarians first: King’s Highway, Bassett’s Creek, but not Beard’s Plaisance. (This apostrophic comment was begun here.) The “pleasure ground” was originally named “The Beard Plaisance.” Perhaps the ground had been Henry Beard’s, but without pleasure. Who knows? By the time the transfer of title to the land from Beard to the park board took place, Beard’s assets were in receivership—not much pleasure in that—and the park board did end up writing his receiver a check for about eight grand. But it’s never been clear to me if that payment was for The Beard Plaisance, Linden Hills Parkway or the Lake Harriet shoreline, all of which belonged to Beard at one point. (Beard built the city’s first consciously “affordable” housing for laborers and their families. He built a block of apartments on Washington Avenue—complete with a sewage system, before the city had one—near the flour mills.)

By the way, King’s Highway was a name given by the park board to a stretch of Dupont Avenue when it asked the city to turn over that section of street as a parkway. The park board did not name Bassett’s Creek; the name was commonly used as the name for the creek about 75 years before the park board acquired the land for a park with that name.

More trivia before we get to the important stuff. The Beard Plaisance is one of four Minneapolis park properties with “the” as part of the official name. There is another with a “the” that is widely used, but was not part of an officially approved name. Can you name the other three parks with an official “the”? Bonus points for naming the one with an unofficial “the”.

Spoiler: I’ll type the names backward to give you time to think. edaraP ehT, llaM ehT, yawetaG ehT. The park property with an unofficial “the”: selsI eht fo ekaL. The lake was named long before the park board was created, and it’s usage was so widely accepted that the park board never had to adopt or approve the name—much like Calhoun, Harriet and Cedar.

Speaking of lake names, which Minneapolis lake had the most names? I’d vote for Wirth Lake, or Theodore Wirth Lake for sticklers. Previously it had been Keegan’s Lake and Glenwood Lake. Part of the original Glenwood Park, which became Theodore Wirth Park, was first named Saratoga Park, but that didn’t include what was then Keegan’s Lake.

Now the Big News for Historians

Historic Minneapolis Tribune. The digital, searchable historic Minneapolis Tribune is now back online. Thank you, thank you to all the people at the Hennepin County Library and the Minnesota Historical Society who worked hard to make this happen. Here’s the link. Woo-hoo! (Thanks to Wendy Epstein for bringing this to my attention.)

Minnesota Reflections. The Minnesota Digital Library has posted about 150 items from park board annual reports at Minnesota Reflections. The items scanned were fold-out plans, maps, charts, tables and photos that could not be properly scanned during the efforts of Google Books, Hathitrust and other libraries to digitize annual reports. Most of the fold-outs had been printed on very fragile tissue paper, so digitization has not only made them accessible, but will preserve them. I hope you have a chance to look at some of them. All were produced while Theodore Wirth was Superintendent of Minneapolis parks, when he was also the landscape architect. So they are especially useful as a means of examining his view of parks and his design priorities.

Keep in mind that most of the plans Wirth presented in annual reports were “proposals” or “suggestions” and many were never built as he first proposed. Some designs were fanciful, others represented an ideal or a wish list of amenities from which the park board usually negotiated more modest facilities. During most of Wirth’s tenure, neighborhood parks were only developed if property owners in the area agreed in advance to pay assessments on their property. Property owners essentially had veto power over park designs they considered extravagant. As plans were scaled down and the price of improvements dropped, more owners were willing to approve the assessments. Wealthier neighborhoods were more likely to approve park facilities than poorer ones, and neighborhoods with more homeowners were more likely to approve plans than neighborhoods with more apartment owners.

After several of his plans were rejected for the improvement of Stevens Square, a residential area that then, as now, was primarily apartment buildings, an exasperated Wirth urged the park board to consult not only landlords, but their tenants as well.

If you’re looking for plans relating to specific parks, you might want to consult the index of annual report plans (foldouts as well as those printed on a single-page), which I published a couple of years ago in Volume I: 1906-1915, Volume II: 1916-1925 and Volume III: 1926-1935.

There will be much more to come from the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board on the Minnesota Reflections site, including Annual Reports and Proceedings in the public domain that are not yet on Google Books or Hathitrust, as well as, we hope, many more published after 1922. We also hope that many historical photos of Minneapolis parks will be added to the site.

Minneapolisparks.org. In case you missed it, the park board introduced a completely new website at minneapolisparks.org this spring One advantage of the new design from a history perspective is that the historical profile of each park property is accessible from its individual park page. You no longer have to download the profiles of all 190 or so parks to get the ones you want. Have a look. The park histories are a good starting point for more research. If you have questions or corrections — or interesting sidebars — on anything in those histories let me know, and I’ll either publish them here or, as appropriate, pass the corrections on to park board staff.

Since the new park pages were introduced, the links to those park histories in my posts here for the past five years are broken. I will try to update them soon, but with more than 230 articles published here, it may take me a while to get to them all.

David C. Smith

Comments (2)

Comments (2)