Archive for the ‘Minneapolis parks’ Category

Longfellow Field: The Park that Bombs Bought

If any park in Minneapolis should be a “memorial” park, perhaps it should be Longfellow Field, because it was bought and built with war profits. It would be hard to explain it any other way. The neighborhood around present-day Longfellow Field is one of the few in the city that didn’t pay assessments to acquire and develop a neighborhood park. That’s because the park board paid for it with profits from WWI.

The story begins with the first Longfellow Field at East 28th St. between Minnehaha Avenue and 26th Avenue South. (There’s a Cub Store there now.) It was once one of the most popular playing fields in the city—and it is the largest playground the park board has ever sold.

The park board purchased the field in the upper right of this photo in 1911 and named it Longfellow Field. This photo, looking northwest, was taken from the top of Longfellow School at Lake St. and Minnehaha Ave. shortly before the land was purchased for a park. Minnehaha runs through the center of the photo and ends at E. 28th St. where the vast yards of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway begin. Minneapolis Steel and Machinery is on the left or west side of Minnehaha. (Charles Hibbard, Minnesota Historical Society)

The origins of that field as a Minneapolis park go back to 1910 when the park board’s first recreation director, Clifford Booth, recommended in his annual report that the city needed a playground somewhere between Riverside Park and Powderhorn Park.

Clifford Booth, shown here in 1910, was the first recreation director for Minneapolis parks and an unsung hero in park history.

It was the only addition he recommended to the playground sites he already supervised around the city.

The following year, the park board found the perfect place within the area Booth suggested: an empty field just off Lake Street, about equidistant from Powderhorn and Riverside, a stones throw from Longfellow School, easily accessible by street car, and it was already used as a playing field. The park board purchased the 4-acre field in 1911 for just over $7,000 and spent another $8,000 to install football and baseball fields, tennis, volleyball and basketball courts, and playground equipment.

An architect was hired to create plans for a small shelter at the south end of the park, but when bids for the shelter came in at more than $10,000, double what park superintendent Theodore Wirth had estimated, the park board decided it couldn’t afford the shelter.

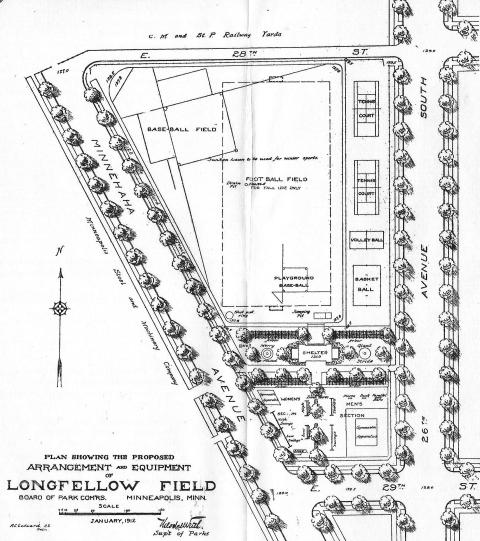

This plan for the development of Longfellow Field was published in the 1911 Annual Report of the park board. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

Despite the absence of a shelter, Wirth wrote in 1912 that Longfellow was one of the most active playfields in the city. Longfellow Field and North Commons were the venues for city football and baseball games for two years while the fields at The Parade were re-graded and seeded. The popularity of the field was attested to by the police report in the 1913 annual report of the park board, which claimed that additional police presence was necessary to control the crowds at football games at Longfellow Field and North Commons.

This Is Where the Intrigue Begins

I was surprised when I learned that the park board sold the park in 1917. The park board had never sold a park before. Why then—after 34 years of managing parks? And why this park? The park board’s explanation in the 1917 annual report was pretty weak, stating only that the field “became unavailable for a playground on account of the growth of manufacturing business in the vicinity.” The property was already on the edge of an industrial zone—see photo above—when it was purchased, so this was no revelation.

Longfellow School, on Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue, was built in 1886 and used until 1918. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The park board resolution on October 17, 1917 to sell the land provided a bit more explanation, but it still seemed less than forthcoming. It wasn’t just the growth of manufacturing business, the resolution claimed, it was also the school board’s decision to close Longfellow School and build a new school farther south. Moreover, the park board claimed that to make the playground useful it would be necessary to invest in improvements and a shelter. Given the other shortcomings of the site, the park board didn’t think it prudent to make those investments at that site.

So the park board declared that the site was no longer useful for a park, a legal requirement to get district court permission to sell the land, and it was sold for $35,000 to the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company.

At the time the park board decided to sell the field it also expressed its intention to find a “more suitable area” for a park and playground nearby in south Minneapolis. Less than two weeks after the sale was announced, the board designated land for a second Longfellow Field, the present park by that name, about a mile southeast in a much less populated neighborhood. The park board paid the $16,000 for the new land—not just four acres, but eight—and for initial improvements to the park from the proceeds of the earlier sale. It was a boon for property owners in the vicinity of the new Longfellow Field: a new park without property assessments to pay for it. The owners of three houses that had just been built across the street from the park must have been thrilled.

When I learned all of this a few years ago, I assumed that in the end the land deal was about the money—the opportunity to sell for $35,000 land the board had bought only six years earlier for $7,000. Even if you subtract the $8,000 spent on improvements, that was a nice return. And to keep that sum in context, remember that the park board shelved plans for a park shelter when bids exceeded estimates by $5,000. Thirty-five grand was a lot of money for a cash-strapped park board.

But the deal still puzzled me, especially because of the unusual way the transaction was introduced in park board records.

Park board proceedings, October 9, 1917, Petitions and Communications:

“From the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company —

Asking the Board to name a price at which it would sell the property included in the tract of park lands known as Longfellow Field.”

Talk about asking to be gouged! Who starts negotiations that way? Name a price? That seemed fishy. So did the speed of the deal. Two committees were asked to report back on the issue the following week, the first indication that someone was in a big hurry to get a deal done. The joint committees not only reported back a week later, they had come up with a price, $35,000, and had essentially concluded the deal. There hadn’t been time for much dickering over the number; the park board had a very motivated buyer. Moreover the board selected land to replace Longfellow Field only two weeks later. As decisive as early park leaders often were, this was unprecedented speed. Too much money. Too fast. Too little explanation.

Perhaps too little deduction on my part as well, but that’s where the matter stood for me the last few years until I decided recently to look into it a bit more as I was compiling a list of “lost parks” in Minneapolis. What I learned is that the decision to sell Longfellow Field had less to do with demographic shifts or manufacturing concentration in south Minneapolis than what was happening in the fields of France and the waters of the North Atlantic.

The United States Joins a World at War

For more than two years, the United States had stayed out of the Great War that embroiled much of the rest of the world. But in early 1917 Germany took the risk that a return to unrestricted submarine warfare and a blockade of Great Britain, including attacks on American ships, could bring about an end to the war before the United States could mobilize its army and economy to have a significant impact on the ground war in Europe. Germany knew that its actions would bring the U.S. into the war—and they did. The U.S. Congress declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917—and began to mobilize in earnest. Part of that mobilization was the enactment of the selective service, or draft, law in May 1917 to build an army. Another part was the procurement of weapons and equipment needed to fight a war.

Of course the manufacturing capacity for war couldn’t be built from scratch. Existing expertise, process and capacity had to be converted to war products. That meant beating plowshares into swords.

That’s where Minneapolis Steel and Machinery came in. In the fifteen years since its founding, Minneapolis Steel had become one of the leading suppliers of structural steel for bridges and buildings in the northwest. That was the “steel” part of the name. The “machinery” was represented most famously by Twin City tractors, but also by engines and parts it manufactured for other companies.

Doesn’t the logo for a line of products from the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company remind you of the logo of our favorite boys of summer? (Thanks to Tony Thompson at twincitytractors.tripod.com)

All I knew about Minneapolis Steel and Machinery was that in the 1920s it was one of the companies that merged to become Minneapolis-Moline and that it was notoriously anti-union. I didn’t know that it was an important military supplier, too.

The first evidence I found of the company’s production for war was a November 10, 1915 article in the Minneapolis Tribune that claimed the company would begin shipping machined six-inch artillery shell casings to Great Britain by January 1, 1916. The paper reported that the initial contract, expected to be only a trial order, was for almost $1.5 million.

Less than two weeks later, another Tribune report made it clear that the company’s involvement in the war was much broader. The paper reported on November 23 an order from Great Britain for 100 tractors from Bull Tractor, another Minneapolis company, for which Minneapolis Steel did the manufacturing and assembly. The tractors, still a relatively new invention, would be shipped from Great Britain to France and Russia to supplant farm horses drafted for war service or already killed in the war. Minneapolis Steel was also shipping 50 steam shovels to be used to dig trenches on the Russian front. Both orders were placed by the London distributor for both Minneapolis Steel and Machinery and Bull Tractor.

Shell orders must have continued for Minneapolis Steel and Machinery after the initial order in 1915, too, because on August 16, 1917 the Tribune reported a new order for the company. Under the headline, “Steel and Machinery Plant to Be Enlarged to Meet Uncle Sam’s Demand for Shells,” the paper reported,

“War orders just taken will necessitate a considerable enlargement of the buildings of the Minneapolis Steel & Machinery company. The company, after completing its shell contract with the British government last spring, decided not to accept any more shell orders, but the United States insisted and a large contract is the result.”

Artillery played an unprecedented role in a war in which both sides were dug into trenches. Blanket bombardments preceded most offensive actions. The result was a French countryside that resembled nothing earthly.

The report, which quoted Minneapolis Steel vice president George Gillette, continued that the company was also manufacturing steam hoists for ships and expected more contracts as the building program progressed. More contracts, unsolicited according to Gillette, did indeed materialize in the next month for carriages for 105 millimeter guns and steering engines for battleships. Those contracts reportedly required a doubling of the company’s manufacturing capacity. At that time government contracts accounted for 75 percent of the company’s output. By early 1918, the Tribune reported that Minneapolis Steel and Machinery had already been awarded $23 million in government contracts.

In the midst of this rash of new military contracts, Minneapolis Steel asked the park board to name its price for Longfellow Field. Even before the district court finished its hearings on the park board’s proposed sale, the company had obtained building permits for three new warehouses, two of them in the 2800 block of Minnehaha Ave., a short foul pop-up from home plate at the former Longfellow Field.

A Civic Duty

The spirit of the times suggests that while money may have been a factor in the park board’s prompt action, it likely was not the primary motivation for selling Longfellow Field. The park board probably viewed the sale as its civic and patriotic duty to assist the war effort—especially given the other valid reasons for moving the playground.

An example of the patriotic fervor generated by the war—to which park commissioners could not have been immune—was a dinner held at the Minneapolis Club, June 12, 1917, to raise funds for the American Red Cross, which was preparing field hospitals to treat wounded soldiers. (Did the army not have a medical or hospital corps?) The next morning the Tribune reported that in one hour the 200 business and civic leaders at the dinner pledged more than $360,000 to the Red Cross. That amount eclipsed the city’s previous one-evening fund-raising record of $336,000 for the building fund for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts a few years earlier.

The report is noteworthy especially for the accounts of the number of men present, among the wealthiest and most influential citizens of Minneapolis, who had sons and nephews on their way to France—so different from the wars of the last four decades.

“Almost every man who rose to name his contribution had a son already in France or on his way. So often did the donor, in making his contribution, add that his boy was wearing the khaki of the army or navy blue that Mr. Partridge (the emcee of the evening) called the roll to ascertain just how many present had sons or nephews in the service. Including two who announced that they themselves were entering the service, the total was 56—mostly sons.”

One of the two men present who was entering military service himself was introduced as Dr. Todd, son-in-law of J. L. Record, who was president of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery. Record pledged $10,000 to the Red Cross on behalf of his company that night.

Ernest G. Wold was one of two WWI pilots from Minneapolis who died in the air over France. The other was Cyrus Chamberlain. (Minnesota Historical Society)

Among others who pledged money were two bankers who had sons in the military aviation services, F. A. Chamberlain, chairman of First and Security National Bank, and Theodore Wold, governor of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank. Both men—and Chamberlain’s wife—were leaders in raising funds for the Red Cross and in selling Liberty Bonds. Their sons never came home. Ernest Wold and Cyrus Chamberlain died in the air over France in 1918. They were jointly honored by having Minneapolis’s airport named Wold-Chamberlain Field, a name that still stands. This was several years before the Minneapolis park board assumed control of building and operating the airport.

The Park Board During the War

Also making pledges at the Minneapolis Club dinner were park commissioners William H. Bovey and David P. Jones. Two other park commissioners who took active roles in the war effort were Leo Harris who resigned from his seat on the park board to enlist and Phelps Wyman who took a leave of absence from the park board to serve as a landscape architect for a group designing new towns for the workers needed at military factories and shipyards.

But it was the president of the park board in 1917 who had the most to lose—or prove—during those days of heated anti-German rhetoric. Francis Gross was the president of the German-American Bank in north Minneapolis. Gross had worked his way up from messenger to the presidency of the bank, which was said to be the largest “non-centrally located” bank in Minneapolis. The bank, founded in 1886, had been located on the corner of Plymouth Avenue and Washington Avenue North since 1905. Gross eventually served 33 years as a park commissioner between 1910 and 1949, earned the nickname “Mr. Park Board,” and had a Minneapolis golf course named for him. He must have been indefatigable, because his name pops up in association with many civic and financial endeavors.

Of all the park commissioners in Minneapolis history, Frank Gross is one of the most intriguing to me. If I could find some cache of lost journals of any of the city’s park commissioners since Charles Loring and William Folwell, I would most want to find those of Frank Gross. He’d be a great interview subject.

In the second year of the war, before the U. S. entry into the conflict, Gross was quoted in the Tribune expressing his view that Germany’s desire for peace was “sincere.” He urged the U. S. and other neutrals to push for peace. “I have no sympathy with the assertion that one side must be victor,” he said. “There can be a fair settlement now on nationality lines.”

Gross’s role in the war effort changed considerably after the U.S. entered the war. The tension of war in the U.S. was underscored when in March 1918, the German-American Bank officially changed its name to North American Bank. Gross asserted that the old name no longer represented the bank’s business or clients, adding “it is not good or desirable that the name of a foreign nationality be attached to an American institution.” In announcing the name change, Gross emphasized that his bank had been the first Minnesota bank to join the federal reserve system in 1915 “to do its part to establish a national banking system in our country so strong and efficient that it could meet any demand our country might make upon it.” (Tribune, March 8, 1918.) Gross’s implicit message: those demands could even include making war on the fatherland of the bank’s founders.

Only three weeks after Gross’s bank changed its name, he went on a speaking tour of towns outside Minneapolis that had large populations of German immigrants or descendants. The Tribune described his visit to Waconia on March 28, 1918. “In line with the belief of the state war savings and Liberty Loan committees that there is a distinct desire in German communities to have the war explained by persons of German birth or descent, Frank A. Gross, president of the North American bank, has spoken to several meetings composed entirely of Germans in the last few days,” the Tribune’s report began. Gross told of how he had circulated among the estimated crowd of 300 people of German descent, mostly farmers, before he spoke and found a “feeling that anyone of German birth or German descent is not wanted as a citizen of this country.”

He ascribed the feeling to the manner in which “overzealous orators” had attacked the German people, “not distinguishing between German imperialism, against which we are making war, and the German people.” Gross said that he then told the people of Waconia they “certainly were wanted as American citizens, but that the citizenship carried with it the responsibility of 100 per cent loyalty to this nation.” Gross said he also dispelled the notion that this was a “rich man’s war,” asking if they thought the “rich would send their boys to war just so their fathers could make a little more money.”

Family experience: My father, who grew up in a small town in rural Minnesota, recounts that his older brother and sister, born before WWI, spoke primarily German before they went to school, but my father and another sister, born after WWI, were never taught German.

Gross later was a prominent speaker at meetings promoting the purchase of Liberty bonds, especially in predominantly German communities such as New Ulm, Hutchinson and Glencoe, and he spoke at “Americanization” meetings—scheduled in Minneapolis neighborhoods with large “foreign elements” according to the Tribune—about “Patriotism.” He shared the podium at one such meeting in north Minneapolis with Rabbi S. M. Deinard whose subject was “The Obligation of the New Generation to the Old” and Mr. E. Avin of the Talmud Torah who gave a patriotic address in Yiddish. Gross also became an instructor, along with future Minneapolis mayor Wallace Nye, at a school for Minneapolis draftees before they were sent off to military camps.

The park board’s annual reports written while Gross was president of the board in 1917 and 1918 reveal very little of the impact of war on parks other than brief references to the heavy burden of taxes and contributions to welfare organizations and the lack of funds for park maintenance. From Gross’s other activities, however, as well as those of other park commissioners, it is apparent that the board would have had a strong sense of patriotic obligation to do what it could to assist the war effort. And that certainly extended to providing expansion space for one of Minneapolis’s largest military suppliers. So the original Longfellow Field became a casualty of war—and the neighborhood surrounding the new Longfellow Field acquired a park without having to pay property assessments.

The Last Link

One connection remains between the descendants of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery and Minneapolis parks. Minneapolis Steel and Machinery built Bull tractors, but the engines were supplied by another local company, the Toro Motor Company. Bull, Toro, get it? One contemporary newspaper account (November 17, 1918), describes Toro as a subsidiary of Minneapolis Steel and Machinery, but the website of The Toro Company today does not claim that connection. (The Toro website does claim the company produced steam steering engines for ships during WWI, however, a product that newspaper reports in 1917 attributed to Minneapolis Steel and Machinery.) Regardless of legal relationship, the two companies were closely connected and Toro is the sole survivor of the Bull, Minneapolis Steel, and Toro tractor trio.

Toro later focused its efforts on lawn-care products, famously lawn mowers, and still specializes in turf management products mostly for parks, athletic fields and golf courses. Each year in recent times, Toro and its employees, along with the Minnesota Twins Community Fund, have donated the materials, expertise and labor to rehabilitate or upgrade a baseball field in a Minneapolis park. These little gems of ball parks now exist in several Minneapolis parks, from Stewart Park to Creekview Park. Thank you, Toro. I don’t know specific park board needs now, but wouldn’t it be appropriate if Toro helped put in a fabulous field at Longfellow Park in honor of the connection long ago?

I’ll leave the final word on WWI in Minneapolis to a preacher.

“I rejoice that I am no longer needed as a partner in the grim business of killing.”

— Rev. Elmer H. Johnson, pastor of Morningside Congregational church who had worked for 11 months at the artillery shell factory of Minneapolis Steel to augment his church salary. (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, December 22, 1918)

David C. Smith

NOTE: Bob Wolff of The Toro Company provides additional details on that company in a “Comment” on the David C. Smith page. (May 31, 2012). In a separate note, Bob said he’d also look into finding photos of the first Toro turf management products used in Minneapolis parks. Stay tuned.

© David C. Smith

Canoe Jam on the Chain of Lakes

The newspaper headline hinted of a sordid affair: “Long Line Waits Grimly in Courthouse Corridor.” Many were so young they should have been in school. Others had skipped work. They stood anxiously in the dim hallway, waiting. News accounts put their numbers at 500 when the clock struck 8:30 that April morning. Many had already been there for hours by then. They prayed they would be among the lucky ones to get permits to store their canoes at the most popular park board docks and on the lower levels of the lakeside canoe racks, so they wouldn’t have to hoist their dripping canoes overhead.

The year was 1912 and nearly 2,000 spaces were available on park board canoe racks and dock slips at Lake of the Isles, Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet. Nearly all of them were needed, which represented a huge increase over the 200 permits issued only two years earlier. The city was canoe crazed.

By contrast, in 2011 the park board rented 485 spaces in canoe racks at all Minneapolis lakes, in addition to 368 sail boat buoys at Calhoun, Harriet and Nokomis.

Canoeing was extremely popular on city lakes, especially after Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun were linked by a canal in 1911, followed by a link to Cedar Lake in 1913. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The demand for canoe racks was so great that park superintendent Theodore Wirth proposed a dramatic change at Lake Harriet at the end of 1912 to accommodate canoeists.

Wirth’s plan (above), presented in the 1912 annual report, would have created a five-acre peninsula in Lake Harriet near Beard Plaisance to accommodate a boat house that would hold 864 canoes. The boat house would have been filled with racks for private canoes, as well as lockers for canoeists to store paddles and gear. The boat house, in Wirth’s words, “would protect the boat owners’ property, and would relieve the shores of the unsightly, vari-colored canoes.”

The board never seriously considered building the boat house and that summer the number of watercraft on Lake Harriet reached 800 canoes and 192 rowboats. Most of the rowboats and about 100 of the canoes were owned and rented out by the park board. Even more crowded conditions prevailed at smaller Lake of the Isles where the park board did not rent watercraft, but issued permits for 475 private canoes and 121 private rowboats.

Rental canoes were piled up on the docks near the pavilion at Lake Harriet ca. 1912. (Minnesota Historical Society)

The park board’s challenge with so many watercraft wasn’t just how to store them, but how to keep order on the lake. An effort to maintain decorum on city lakes began in April 1913 when another year of permits was issued. The park board announced before permits went on sale that because of “considerable agitation about objectionable names” on boats and canoes the year before, permits would not be issued to canoes that bore offensive names.

The previous summer newspapers reported that commissioners had condemned naughty names such as, “Thehelusa,” “Damfino,” “Ilgetu,” “Skwizmtyt,” “Ildaryoo,” “O-U-Q-T,” “What the?,” “Joy Tub,” “Cupid’s Nest,” and “I’d Like to Try It.” The commissioners decided then that such salacious names would not be permitted the next year, even though Theodore Wirth urged the board to take the offending canoes off the water immediately.

When the naming rules were announced the next spring, park board secretary J. A. Ridgway was given absolute power to decide whether a name was acceptable. To begin with he allowed only monograms or proper names, but used his discretion to ban names such as “Yum-Yum” even though that was the name of a character in Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Mikado.” Even proper names could be improper.

Despite the strict naming rules, all but 75 of the park board’s 1400 canoe rack spaces were sold by late April, and practically all remaining spaces were “uppers” scattered around the three lakes.

The crackdown on canoe-naming wasn’t the end of the park board protecting the morals of the city’s youth on the water however. Take a close look at the 1914 photo below by Charles Hibbard from the Minnesota Historical Society’s collection.

The photo shows canoeists listening to a summer concert at the Lake Harriet Pavilion. Notice the width of the typical canoe and how two people could sit cozily side-by-side in the middle of the canoe. Now imagine how easy it would be to drift into the dark, get tangled up with the person next to you and make the canoe a bit tippy. Clearly a safety issue.

The Morning Tribune announced June 28, 1913 that the park board would have no more of such behavior. “The park board decided yesterday afternoon, ” the paper reported, “that misconduct in canoes has become so grave and flagrant that it threatens to throw a shadow upon the lakes as recreation resorts and to bring shame upon the city.”

The solution? A new park ordinance required people of opposite sex over the age of 10 occupying the same section of a canoe to sit facing each other. No more of this side-by-side stuff, sometimes recumbent. According to the paper, park commissioners said the situation had become one of “serious peril to the morals of young people.” Park police were given motorized canoes and flashlights to seek and apprehend offenders.

The need for flashlights became evident after seeing the park police report in the park board’s 1913 annual report. Sergeant-in-Command C. S. Barnard, referring to the ordinance that parks close at midnight, noted a policing success for the year. To get canoeists off the lake by midnight, the police installed a red light on the Lake Harriet boat house that was turned on to alert lake lovers that it was near 11:30 pm, the time canoes had to leave the lake. Barnard reported that the red light “has been a great help in getting canoeists off the lake by 11:30 p.m., but owing to the large number who stay out past that time (emphasis added), I would suggest that the hour be changed to 11 o’clock in order to enable the parks to be cleared by 12 o’clock.”

Indignant protest against the side-by-side seating ban arose immediately. Arthur T. Conley, attorney for the Lake Harriet Canoe Club, suggested that the park board show a little initiative and arrest those whose conduct was immoral rather than cast a slur on “every woman or girl who enters a canoe.” If Conley believed the ordinance was a slur on men and boys as well he didn’t say so, but he did add, “We dislike to hear that we are engaged in a sport which is compared with an immoral occupation and that we are on the lake for immoral purposes.”

In the face of protests, the new ordinance was not vigorously enforced and was repealed before the start of the 1914 canoe season. The Tribune noted in announcing the repeal that “the public did not take kindly to the ordinance last year and boat receipts at Lake Harriet fell off considerably on account of it.”

Despite the repeal of the unpopular ordinance, boating fell off even more in 1914. In the annual report at the close of the year Wirth attributed the decline partly to a terrible storm that passed over Lake Harriet on June 23 resulting in the drowning of three canoeists. Newspapers reported dramatic rescues of several others. By 1915 the number of canoe permits had dropped under 1400 even though canoe racks had been added to Cedar Lake, Glenwood (Wirth) Lake and Camden Pond.

The popularity of canoeing continued to decline. Wirth noted in 1917 that there had been a very perceptible decrease again in the number of private boats and canoes on the lakes. While he attributed that decline partly to unfavorable weather, he also noted the “large number of young men drawn from civil life and occupations to military service” as the United States entered WWI.

There were only six sail boats on city lakes in 1917, and all six were kept on Lake Calhoun. The first year that the park board derived more revenue from renting buoys for sail boats than racks for canoes was not until 1940. From then until now sailing has generated more revenue for the park board than canoeing.

The number of canoe permits leveled off for a while in the 1920s at about 1000 per year, but the canoe craze on the lakes had passed, much as the bicycle craze of the 1890s. During the bicycle craze the park board had built a corral where people could check their bikes while at Lake Harriet. That corral held 800 bicycles. At the peak of the much shorter-lived canoe craze in the 1910s, the park board provided rack space at Lake Harriet for 800 canoes. Popular number. Fortunately, the park board did not build permanent facilities—or a peninsula into Lake Harriet—to accommodate a passing fad.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Minneapolis Park Memory: Ski Jumping at Wirth Park

I have received several very interesting comments from Jim Balfanz on my post about the history of ski jumping in Minneapolis. Today he sent me this photo of him (left) and his brother John, both champion skiers, in a double jump at Wirth Park in 1956. Jim copied the photo from the West High School yearbook of 1956. The original photo was “courtesy of the Minneapolis Tribune.”

In his comments, Jim has provided the names of many people who were important in Minneapolis ski jumping at a time when Minneapolis was producing national champions and Olympians.

If anyone else has memories, stories or photos to add either as comments on that post or in e-mails to me, I’d be delighted to post them.

Thanks to Jim and also to Jay Martin for his comments.

David C. Smith

Yard and Garden Show: Trees in Minneapolis

I’ll be the entertainment on the Yard and Garden Show, Saturday, February 4 at noon on WCCO radio, 830 AM. I’ll talk about how the Minneapolis park board became responsible for all the street trees in the city. Did you know that most of Minneapolis south and west of the Mississippi was once open prairie? Then where did all these trees come from? The park board planted most of the trees along our streets—and still owns them. But did you know that’s also one reason the Minneapolis park board has its own police force? Of course, Charles Loring deserves most of the credit; his love of trees was well-known.

Portius Deming, writing in the park board’s 1916 annual report, described a major event that year that so logically connected Loring and trees:

It was a splendid idea to convert the conventional “Arbor Day” into “Charles M. Loring Day,” and it is to the credit of Minneapolis that this suggestion met with instant and universal approval.

“Loring Elms” were planted and dedicated to Loring by children at 78 public schools in the city that day and the Mayor planted a “Loring Elm” in Loring Park. Loring was in his 80s at the time and was still at his winter home in Riverside, California, but his papers at the Minnesota Historical Society include many telegrams he received from well-wishers that day.

Learn more at noon Saturday. Perhaps I’ll recap here afterward.

David C. Smith

The Preservation Instincts of Charles M. Loring

Charles Loring’s view on preserving natural landscapes was so well-known that this anonymous poem appeared in the St. Paul Daily Globe on September 8, 1889 in a humor column, “All of Everything: A Symposium of Gossip About Minneapolis Men and Matters.”

A grasping feature butcher,

With adamantine gall,

Wants to build a gallery

At Minnehaha’s fall.He wants to catch the people

Who come to see the falls,

And sell them Injun moccasins

And beaded overalls.He wants to take their “phizes,”

A dozen at a crack,

With the foliage around them

And the water at the back.But the shade of Hiawatha

No such sacrilege would brook:

And he’d shake the stone foundations

Ere a “picter had been took.”C. M. Loring doesn’t like it,

For he says he’d like to see

The lovely falls, the creek, the woods,

Just as they used to be.

Loring had chaired a commission appointed by the governor to acquire Minnehaha Falls as a state park in 1885. The land was finally acquired, after a long court fight over valuations, in the winter of 1889. (The total paid for the 180-plus acres was about $95,000.) See City of Parks for the story of how George Brackett and Henry Brown took extraordinary action to ensure the falls would be preserved as a park.

The poem in the Daily Globe appeared because the park board was considering permitting construction of a small building beside the falls for the express purpose of taking people’s photos with “the water at the back.” And of course charging them for the privilege.

That proposal elicited a sharp response from landscape architect H. W. S. Cleveland who also opposed having any structure marring the natural beauty of the falls. Cleveland used language much harsher than the reserved Loring likely would have used. In a letter to his friend William W. Folwell, Cleveland wrote on September 5, 1889,

I cannot be silent in view of this proposed vandalism which I am sure you cannot sanction, and which I am equally sure will forever be a stigma upon Minneapolis, and elicit the anathema of every man of sense and taste who visits the place.

If erected it will simply be pandering to the tastes of the army of boobies who think to boost themselves into notoriety by connecting their own stupid features with the representation of one of the most beautiful of God’s works.

The preservation passion of Loring and Cleveland is evident today in the public lakeshores and river banks throughout Minneapolis. The next time you take a stroll around a lake or beside the river, or fight to acquire as parks the sections of the Mississippi River banks that remain in private hands, say a little “thank you” to people like Loring and Cleveland who saw the need to acquire lakes and rivers as parks more than 125 years ago—and nearly got them all.

And the photography shack was never built.

David C. Smith

Recommended Reading from Horace W. S. Cleveland

We haven’t had much of a winter yet in Minnesota, but it’s inevitable. When it comes and you’re imprisoned in your cozy den, your thoughts may turn to spring and the gardens you’ll plant or visit. To get you thinking about warmer weather, I’m providing a reading list from the man who envisioned Minneapolis’s park system and designed the first parks acquired by the Minneapolis park board in the 1880s.

In 1886, the secretary to the Minneapolis park board, Rufus J. Baldwin, apparently asked landscape architect Horace W. S. Cleveland to recommend books on his profession. It’s not clear if Baldwin was interested in furthering his own education (he was a prominent Minneapolis attorney) or if he was acquiring books for the park board. Below is Cleveland’s reply dated 23 Sep. 1886.

(All of the books Cleveland cited are now available free online at Google Books. The links in the letter take you to the online volume of the work cited.)

In considering your request that I would furnish you a list of desirable works on landscape gardening I find the subject growing in my mind so rapidly and attaining such dimension that the chief difficulty lies in making a judicious selection. The literature of the last century was especially rich in the discussion of the principles on which the art is founded. “Repton’s Landscape Gardening” is perhaps the ablest and most elaborate of the works of that date, but I think I learned more of first principles from the “Essays on the Picturesque, By Sir Uvedale Price,” than from any book.

It is doubtful however whether either of these books can be purchased in this country unless by chance at a second-hand store. “Loudon’s Encyclopedia of Horticulture,” contains perhaps the most detailed, practical instructions of any English work and is still a standard of reference and can be had in England though it has not been republished here.

“Downing’s Landscape Gardening” is at the head of all works on the subject in this country and is in fact a compilation and adaptation to our wants of all the essential principles of the best foreign writers. Next to that and in fact supplying much in which Downing’s work is deficient is “Country Life By Robert Morris Copeland.” He was for many years my partner and was a man of rare taste and skill, and his book is an admirable one. “Scott’s Suburban Homes,” is also an excellent treatise and full of judicious advice in regard to the arrangement of grounds and tasteful use of trees and shrubbery. These books can be procured of any of the leading booksellers or at the seed stores of the principal cities. In ordering Downing’s book, be sure to get the edition which has the appendix by Winthrop Sargent, which contains a vast amount of very valuable information.

I do not think of any other work directly devoted to the subject that would add to the value of what is contained in the above.

“The Horticulturist” during the time it was edited by Downing was rich in essays on different branches of useful ornamental gardening, but it is doubtful if a complete set could be had, and indeed the three works above enumerated comprise I think all the essential principles so far as they can be given by print and illustration.

If I think of others that would be desirable I will let you know.

The letter is signed, “Very truly yrs, H.W.S. Cleveland.”

(The original letter is in the files of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board at Special Collections, Minneapolis Central Library, Hennepin County Library.)

Amazing, isn’t it, that works Cleveland cited as unavailable in the United States in 1886 — or available at “the seed stores of principal cities” — are now free to anyone with access to a computer. Some people have a problem with a company such as Google having so much control over information — I just read The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry) by Siva Vaidhyanathan — and while I agree with concerns over the concentration of information control, the widespread availability of so much information, even as old and arcane as these texts, is an invaluable resource.

Happy reading.

David C. Smith

P.S. Minneapolis still doesn’t have a park named for Horace W. S. Cleveland — and we should. I’m still in favor of naming the west side of the Mississippi River Gorge for him.

Ostrich in the Park: This Month’s Contest

Here’s your chance to win a free subscription to minneapolisparkhistory.com. Do what the Minneapolis park board said it couldn’t afford to do—put an ostrich in a Minneapolis park. Of course the park board refused an offer to put real ostriches in parks, but all you have to do to be this month’s lucky winner is photoshop an ostrich into your favorite park picture and send it to us at minneapolisparkhistory[at]q.com.

An ostrich admiring Minnehaha Falls, canoeing in Lake of the Isles, stealing a golf ball at Gross, or skating at Logan Park. Imagine the possibilities.

The inspiration for this contest was an item in the February 24 issue of the Minneapolis Morning Tribune in 1913. The headline proclaimed:

No Ostriches This Year

Park Board Can’t Buy Birds

Yet Because of Slimness in

Public Pocket Book

“There are to be no ostriches imported this year to add to the attractions of the parks,” the Tribune reported. “Much though Superintendent Wirth would like to see the large birds roaming through the parks, he readily acquiesced when the park board, for reasons of economy, refused the offer of a California ostrich farmer to stock the parks with ostriches at relatively small cost. Mr. Wirth and some of the park commissioners hope, however, that by next year the board’s finances will allow the purchase of at least a limited number of ostriches.”

And John Erwin and Jayne Miller think they’re being squeezed by lack of funds!

If the park board had found the funds to buy ostriches in 1913, the birds would have joined deer, elk and buffalo that roamed the hillside at Minnehaha Park in the park board’s menagerie. The much larger animal collection kept at the Minnehaha Park from the mid-1890s—including bear, mountain lion, sea lions, alligators and exotic birds—were given to Fish Jones for his private zoo at Longfellow Garden in 1907. The park board kept the deer and elk at Minnehaha until 1923.

Wirth’s other notable contribution to the Minneapolis bestiary was the gray squirrel. Wirth imported the gray squirrels from Kansas in 1909 to replace the red squirrels he hired someone to shoot in Loring Park because they were eating songbird eggs. Wirth believed the less aggressive grays would make better neighbors. He noted in 1919 that the gray squirrels had extended their range throughout the city.

I doubt the ostriches would have been quite as adaptable. And I bet they would have made a bigger mess than the geese that many park visitors and neighbors despise.

Do you know what Fish Jones paid for the animals he got from the park board’s Minnehaha Park zoo in 1907? He had to provide free admission to his zoo one day a week—usually Saturday.

David C. Smith

The Two Pieces of Thomas Lowry Park

After an exchange of several e-mails with Bill Payne on the history of Thomas Lowry Park, I thought I should post the rest of what I know about the former Mt. Curve Triangles. (See the first of my exchanges with Bill in the comments section of the “About” page; and see the posts that generated his questions here and here.) After reading my posts and the historical profile of Thomas Lowry Park at the park board’s website, Bill questioned whether all of the park had ever been called Douglas Triangle before the park was officially named Mt. Curve Triangles on November 4, 1925. I think Bill is right that the larger part of the park—perhaps all of it—never had an official name until then.

On this 1903 map there is no “triangle” of land bounded by Bryant, Douglas and Mt. Curve, center right, at what would become Thomas Lowry Park. (John S. Borchert Map Library, University of Minnesota)

The questions arise because Thomas Lowry Park comprises two parcels of land acquired at different times: the tiny triangle—0.07 acre—bordered by Douglas Avenue, Mt. Curve Avenue and Bryant Avenue South and the much larger quadrangle—2.25 acres—between Douglas and Mt. Curve, Colfax and Bryant. This was before Bryant Avenue between Douglas and Mt. Curve was closed.

The 1903 plat map of Minneapolis at left doesn’t show a triangle of land at all east of Bryant. So it’s nearly certain that requests in 1899 from residents of the area, including Thomas Lowry, whose house is upper right on the map, that the park board maintain the grounds between Mt. Curve and Douglas apply to the lot between Bryant and Colfax. The park board denied that request because it didn’t own the land.

The park board’s first acquisition there is a bit cloudy. For all the details…

Stone Quarry Update: Limestone Quarry in Minnehaha Park at Work

I was technically correct when I wrote in October that the park board only operated a limestone quarry and stone crushing plant in Minnehaha Park for one year: 1907. But I’ve now learned that the Minnehaha Park quarry was operated for nearly five years by someone else—the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

From early 1938 until 1942 the WPA, a federal program that provided jobs during the Depression, operated the quarry after “tests revealed a large layer of limestone of hard blue quality near the surface” in the park near the Fort Snelling property line at about 54th, according to the park board’s 1937 Annual Report. The WPA technically operated the plant, but it was clearly for the benefit of the Minneapolis park system.

“Although this plant is operated by the WPA, our Board supplied the bed of limestone, the city water, lighting, gasoline and oil, and also some small equipment, since it was set up primarily for our River Road West project, which included the paving of the boulevard from Lake Street to Godfrey Road, and also to supply sand and gravel to the River Road West Extension project (north from Franklin Avenue) where there was a large amount of concrete retaining wall construction.”

— 1938 Annual Report, Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners

In 1938 the park board estimated that 85% of the product of the stone crushing plant was used on park projects, the remainder on other WPA projects in the city.

The quarry was established in an area that “was not used by the public and when the operations are completed, the area can be converted into picnic grounds and other suitable recreational facilities,” the park board reported. (I bet no one thought then that a “suitable” facility would include a place where people could allow their dogs to run off leash!)

“The Stone-crushing Plant at Minnehaha Park” (1938 Annual Report, Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners) Doesn’t look much like one of our favorite wild places, does it?

The plant consisted of “two large jaw crushers” and a conveyor that lifted the crushed rock to shaker screens over four large bins. It was operated by gasoline engines and was lit by electric lights so it could operate day and night. (The fellow with the wheelbarrow in the photo might have liked more conveyor.)

The crushed stone was used in paving River Road West and East, Godfrey Road and many roads, walks and tennis courts throughout the park system. The rock was also used as a paving base at the nearby “Municipal Airport,” also known as Wold-Chamberlain Field, which the park board owned and developed until it ceded authority over the airport to the newly created Metropolitan Airports Commission in 1944. According to the 1942 Annual Report of the park board, in four-and-a-half years the quarry produced 76,000 cubic yards of crushed limestone, 50,000 cubic yards of sand and gravel and 36,000 cubic feet of cut limestone.

The cut limestone was used to face bridges over Minnehaha Creek, shore retaining walls at Lake Harriet, Lake Nokomis and Lake Calhoun and other walls throughout the park system.

The plant was used to crush gravel only in 1938. The gravel was taken from the banks of the Mississippi River, “it having been excavated by the United States Government to deepen the channel of the Mississippi River just below the dam and locks.” After that, the WPA acquired the sand and gravel it needed from a more convenient source in St. Paul.

The project was terminated in 1942 near the end of the WPA. In his 1942 report, park superintendent Christian Bossen wrote in subdued tones that, “For a number of years, practically the only improvement work carried on was through WPA projects. In 1942, WPA confined its work almost exclusively to war projects: and under these conditions considerable work was done at the airport and a very little work was done on park projects.” The WPA was terminated the following year.

The next time you take your dog for a run at the off-leash recreation area at Minnehaha, have a look to see if there are any signs of the quarry and let us know what you find.

David C. Smith

Name That Park

1. This Minneapolis park is commonly refered to by a name that indirectly commemorates one of the most famous people in the history of the United States, a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the U. S. Constitution.

2. The man for whom the park is named built this house at 5th Street and 12th Avenue SE in 1883.

3. The namesake of this park, pictured below, was one of three civic leaders in Minneapolis in the 1870s and later who acquired their social, political and economic influence after serving in the Confederate army, unusual for this famously “Yankee” town.

This Kentuckian entered the Confederate army at age 19 and finished the Civil War as a prisoner of war. The other prominent Confederate soldiers in Minneapolis were Thomas Rosser, a Confederate general, who was the city engineer in 1878, and Phillip “P. B.” Winston, Rosser’s aide during the war, who was elected Minneapolis mayor in 1890. Winston married Katherine Stevens, the daughter of Minneapolis pioneer Col. John Stevens. Katharine donated the sculpture of her father that now stands near Minnehaha Falls.

In the History of the City of Minneapolis, Minnesota, Isaac Atwater addressed in 1893 this man’s Civil War service thirty years earlier:

A generation has passed since the war of the Rebellion. The survivors of its contests in arms have passed the meridian of life. Their animosities have softened, their judgments matured, and their love for a common Union strengthened, or if once alienated, has been restored. Those who once wore the blue fraternize with those who donned the gray, and the acrimonies which were once bitter between them have melted into common respect. Minneapolis entered into the struggle with enthusiasm and sent her choicest citizens to the front. But she has always been kind and tolerant to those who were on the other side. Her cosmopolitan citizenry cherish neither bigotry nor proscription…With courtesy and forbearance she received Mr.______ after the war was over and entrusted to him her dearest interests and placed upon him her chief honors. And no one born within her own limits, and following her tattered flags, could more loyally or honorably bear them than he.

More than a bit flowery, but apparently a subject that Mr. Atwater believed needed to be addressed. The man described served on the city council from the late 1870s, the first park board in 1883 and the school board 1884-1891. He was a trustee of Hamline University, a regent of the University of Minnesota, and president of the state agricultural society.

4. He made his fortune in lumber, but he also founded a planing and shingle company that bore his name and once occupied the property that is now a park.

This is the view of the mystery park looking east from Boom Island in 1901 — when Boom Island was still an island. (Minnesota Historical Society)

And the Answer Is…

The park in question has never been named officially, but it is commonly referred to as the B. F. Nelson site, after the company that occupied the property for nearly 100 years. The company was created by Benjamin Franklin Nelson in the 1880s.

B. F. Nelson was not one of the commissioners named in the legislation that created the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners in 1883, but shortly after the act passed the legislature and was approved by a referendum in Minneapolis, one of the named commissioners, Andrew Haugan, resigned. The other commissioners elected Nelson to take Haugan’s place until the first election of park commissioners in 1884. Since then park commissioners have been elected, although as in Nelson’s case, vacancies between elections are filled by a vote of the other commissioners. Nelson chose not to stand for election to the park board in 1884, opting instead for a seat on the school board.

Nelson was one of three park commissioners who resided east of the river—Samuel Chute and John Pillsbury were the others—who selected the site of Logan Park as the first east-side park in 1883.

David C. Smith

More Bassett’s Creek

Interesting thoughts from readers on city and park board treatment of Bassett’s Creek:

Is it possible that Minneapolis spent as much or more tunneling Bassett’s Creek in an attempt to improve north Minneapolis than it spent building a parkway along Minnehaha Creek? Someone would have to go through financial reports to determine the city/Bassett’s Creek figures. Building two tunnels, the second one 80 feet beneath downtown Minneapolis, must have had a fairly hefty price tag. What if you threw in the federal and park board dollars from the time of Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration projects in the 1930s until now on Bassett’s Creek above ground from Bryn Mawr into Theodore Wirth Park?

Perhaps the park board’s biggest missed opportunity in dealing with Bassett’s Creek was the decision to build a competition-quality youth sports complex—the one named for Leonard Neiman—at Fort Snelling instead of in Bryn Mawr/Harrison. I don’t recall what Bryn Mawr or Harrison residents thought of the idea when it was considered in the late 1990s. Does anyone remember that discussion? It would certainly be a better location for youth sports than the distant fields of Fort Snelling (for people living almost anywhere in Minneapolis—south, north, northeast, or southeast). Whether building that complex in the central city would have spurred other development or at least raised awareness of Bassett’s Creek is hard to say, but it could’ve been positive for the neighborhoods beside and above the creek.

David C. Smith

The Myth of Bassett’s Creek

I heard again recently the old complaint that north Minneapolis would be a different place if Bassett’s Creek had gotten the same treatment as Minnehaha Creek. Another story of neglect. Another myth.

You can find extensive information on the history of Bassett’s Creek online: a thorough account of the archeology of the area surrounding Bassett’s Creek near the Mississippi River by Scott Anfinson at From Site to Story — must reading for anyone who has even a passing interest in Mississippi River history; a more recent account of the region in a very good article by Meleah Maynard in City Pages in 2000; and, the creek’s greatest advocate, Dave Stack, provides info on the creek at the Friends of Bassett Creek , as well as updates on a Yahoo group site. Follow the links from the “Friends” site for more detailed information from the city and other sources.

What none of those provided to my satisfaction, however, was perspective on Bassett’s Creek itself after European settlement. A search of Minneapolis Tribune articles and Minneapolis City Council Proceedings, added to other sources, provides a clearer picture of the degree of degradation of Bassett’s Creek — mostly in the context of discussions of the city’s water supply. This was several years before the creation of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners in 1883 — a time when Minnehaha Creek was still two miles outside of Minneapolis city limits. The region around the mouth of Bassett’s Creek was an economic powerhouse and an environmental disaster at a very early date — a mix that has never worked well for park acquisition and development.

Idyllic Minnehaha Creek, still in rural surroundings around 1900, quite a different setting than Bassett’s Creek, which had already been partly covered over by then. (Minnesota Historical Society)

“A Lady Precipitated from Bassett’s Creek Bridge”

Anfinson provides many details of the industrial development of the area around the mouth of Bassett’s Creek from shortly after Joel Bean Bassett built his first farm at the junction of the river and the creek in 1852. By the time the Minneapolis Tribune came into existence in 1867, industry was already well established near the banks of the creek. A June 1867 article relates how the three-story North Star Shingle Mill had been erected earlier that year near the creek. The next March an article related the decision to build a new steam-powered linseed oil plant near the creek on Washington Avenue.

Even more informative is a June 27, 1868 story about an elderly woman who fell from a wagon off the First Street bridge over the creek. “A Lady Precipitated from Bassett’s Creek Bridge, a Distance of Thirty Feet,” was the actual headline. (I’m a little embarrassed that I laughed at the odd headline, which evoked an image of old ladies raining down on the city; sadly, her injuries were feared to be fatal.) But a bridge height of thirty feet? That’s no piddling creek — even if a headline writer may have exaggerated a bit. The article was written from the perspective that the bridge was worn out and dangerous and should have been replaced when the city council had considered the matter a year earlier. Continue reading

Comments (13)

Comments (13)