Keep Your Thomas Lowrys Straight

Just to be clear: the Thomas Lowry Memorial is not in Thomas Lowry Park. Neither is it in Lowry Place. (See February 25 post: Lost Minneapolis Parks: Virginia Triangle.)

The Thomas Lowry Memorial, with his statue, was originally erected in 1915 on Virginia Triangle across Hennepin Avenue and a bit south from Thomas Lowry’s mansion on Lowry Hill. Thomas Lowry’s mansion was eventually purchased by Thomas Walker who then created the Walker Art Center on the site.

Thomas Lowry’s home in 1886 looking north over what is now The Parade and the Sculpture Garden. (Minnesota Historical Society)

When Virginia Triangle was erased in 1967 by freeway plans, Thomas Lowry’s statue was not moved to Thomas Lowry Park, because it didn’t exist yet, at least by that name. And it wasn’t moved to Lowry Place, also called Lowry Triangle, another lost park property, because it had already ceased to exist. Virginia Triangle was where northbound Lyndale and Hennepin avenues met at Groveland; Lowry Place was where they parted again at Vineland and Oak Grove.

Lowry Triangle is on the immediate left as you look north on Hennepin Avenue toward the Basilica. Oak Grove Street and Loring Park are on the right. Vineland Avenue, leading to the Walker Art Center, is on the left. Virginia Triangle and Thomas Lowry’s Memorial are directly behind you in 1956. (Norton and Peel, Minnesota Historical Society)

Lowry Triangle, officially named Lowry Place on May 15, 1893, was acquired by the park board from the city in 1892. The park board asked the city to hand over the triangle on November 2, 1891. It was slightly smaller than Virginia Triangle to the south. Lowry Place was at one time intended to be the home of the statue of Ole Bull that in 1897 ended up in Loring Park. Park board president William Folwell wrote to Thomas Lowry to ask if he objected to Ole Bull’s statue being placed across Lyndale Avenue from Lowry’s house on a park property that bore his name. Lowry replied that he appreciated the courtesy of being asked and had no objection. I don’t know why the statue was then placed in Loring Park instead. If you do, please tell. That’s not all I don’t know: I also don’t know why Lowry’s memorial was placed originally on Virginia Triangle instead of Lowry Triangle.

By the time the Lowry Memorial had to be moved in 1967 it was too late to shift it to the Lowry Triangle; that little patch of ground (0.16 acres) had already been acquired by the State of Minnesota in 1964 in anticipation of reconfiguring streets for the construction of I-94.

Moving the memorial to Thomas Lowry Park wasn’t an option then because at that time what is now Thomas Lowry Park at Douglas Avenue, Bryant and Mt. Curve was named Mt. Curve Triangles. That isn’t a typo, it was officially named Mt. Curve Triangles, plural, in November 1925 when its name was changed from Douglas Triangle. That was perhaps done to distinguish it from Mt. Curve Triangle, singular, which had been the name of a tiny street triangle at Fremont and Mt. Curve since 1896. That triangle was renamed Fremont Triangle in 1925, when the Mt. Curve name was shifted a few blocks east to Douglas Triangle. Mt. Curve Triangles was nearly 1.5 acres while Fremont Triangle was only .02 acre.

Thomas Lowry Park in 1925 when it was still Douglas Triangle, before it became Mt. Curve Triangles. You can find other images of the property at the Minnesota Historical Society’s Visual Resources Database, but only if you search for Douglas Triangle or Mt. Curve Triangle, not Thomas Lowry Park. (Hibbard Studio, Minnesota Historical Society)

To confuse matters, the popular name for the property was neither Douglas Triangle, nor Mt. Curve Triangles, nor Thomas Lowry Park, but “Seven Pools” after the number of artificial pools designed for the park by park commissioner and landscape architect Phelps Wyman in 1923.

Thomas Lowry and his name had nothing to do with Mt. Curve Triangles, other than the fact it was located on Lowry Hill near his old mansion, until residents in the neighborhood campaigned to have the park renamed for Lowry in 1984. (Lowry did ask the park board to improve and maintain the land in 1899, but his request was refused because the park board didn’t own the land then. It didn’t purchase the land until 1923.)

Given that there was no other place named Lowry to put the memorial to Thomas Lowry the park board chose Smith Triangle at Hennepin and 24th. That’s where it still is. The only connection between Smith and Lowry is that they probably knew each other.

Of course neither the Lowry Memorial nor Lowry Park are anywhere near Lowry Avenue, which is miles away in north and northeast Minneapolis. Lowry Avenue is much closer to the former site in Northeast Minneapolis of the Lowry School, which no longer exists either. Lowry School figured prominently in plans for Audubon Park in the 1910s. When Lowry School was built in 1915, Buchanan Street between the school and Audubon Park was vacated with the idea that the park would serve as the playground for the school.

Thomas Lowry School in 1916 showing Buchanan Street vacated between the school and Audubon Park at left. (Minneapolis Public Schools)

Those plans were never formalized. While the park provided space, it didn’t provide play facilities. Playground facilities weren’t developed at Audubon Park until the late 1950s. By that time Lowry School was already outdated and destined for closure. (For more photos of Lowry School click here.)

You can learn more about all of these park properties and how they were acquired, developed and named at the web site of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: Rauen Triangle

Minneapolis lost one of its only parks named for someone with a German surname in 1939. Given that more Minneapolitans define their ancestry as German than any other nationality — nearly one in four — it seems a bit odd that a city with more than 180 parks would have so few named after people of German descent. As I was looking over a list I compiled of Minneapolis park properties that no longer exist, I was struck by the description of Rauen Triangle; a 1930s park inventory claimed that the triangle was named after “German settler” Peter Rauen. When that triangle was paved over in 1939, the only park property that remained with a German name was Humboldt Triangle in north Minneapolis. Alexander von Humboldt was a German naturalist and explorer who died in 1859. Even Humboldt’s name adorned a park property by default rather than by choice; the triangle took its name from its location on Humboldt Avenue.

Rauen Triangle was a small piece of land (0.03 acre) at the oddly configured intersection of 11th Avenue North, North Fifth Street and North Sixth Street. The park board purchased the land at the request of residents of the neighborhood in 1890 for $3,462 — a price that seems exorbitant for such a small, otherwise useless tract. The entire cost was assessed on property in the neighborhood. It was given the unimaginative name of Fifth Street Triangle.

If the Nomenclature Committee had had its way in May 1893 the triangle would have been renamed Iota Triangle. The committee of Harry Wild Jones, William Folwell and Patrick Ryan had suggested naming most of the small street triangles after letters of the Greek alphabet. The park board approved many other names recommended by the committee that day — Kings Highway, The Beard Plaisance, Logan Park, Windom Park, and Van Cleve Park — but returned the Greek alphabet names to the committee for further consideration. Good choice.

The only suggested park name recommended by the committee that was shot down completely by the board was the name Hiyata Park for Spring Lake Park, the small pond at the foot of Kenwood Hill behind the Parade Ice Arena. The board voted to keep the name Spring Lake. Hiyata, the committee claimed, was an “Indian name meaning Back-By-The-Hill.”

After further deliberation, instead of Iota Triangle the committee returned with a recommendation of Rauen Triangle in honor of Peter Rauen, a German who had arrived at St. Anthony in 1856. The name made sense because Peter Rauen’s home at 1101 North Sixth Street faced the triangle.

Peter Rauen’s house at 1101 North Sixth Street, about 1875. This photo was taken from approximately the site of the future Rauen Triangle. I like the board sidewalk. (Michael Nowack, Minnesota Historical Society)

Rauen operated a successful grocery and general merchandise store at the corner of Plymouth and Washington. He was an alderman on the first city council after the merger of St Anthony and Minneapolis in 1872 and he was mentioned in Horace Hudson’s early history of Minneapolis as a prominent president of the Harmonia Society, one of the more successful musical organizations in the early days of Minneapolis.

The park board gave up Rauen Triangle in 1939 to the city of Minneapolis. On the same lot that Rauen’s home had once stood, the city built Fire Station 4, which still stands on the site. It seems that the triangle got in the way of the long hook and ladder fire engines maneuvering into the station. The triangle was paved over to create a quite wide intersection.

In Rauen’s time the neighborhood was all residential, but it is now completely industrial and hemmed in by freeways.

Since the demise of Rauen Triangle, two other Minneapolis parks have been named for people with German surnames: Mueller Park (1973) and Gluek Park (1995).

I don’t mention the nationality or ethnicity of park names as something that needs to be addressed; it is simply an observation. The only name missing from a Minneapolis park that really must be added is Horace Cleveland’s.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Minneapolis Park Hero: Alice Dietz

Early in my research of Minneapolis park history for City of Parks, Alice Dietz caught my attention. She had a forty-year career in Minneapolis parks, 1916-1957. She rose to prominence in the park system quickly from her start as a recreation director. In January 1918, the park board received a letter from an appreciative mother asking that Dietz be reappointed as recreation director at Maple Hill (Beltrami) Park. She was not reappointed at Maple Hill; in the park board’s annual report for 1918 Dietz was singled out for praise for her work at bigger, busier Bryant Square Park. The next year Dietz moved again, this time to the most visible and important recreation job in the city as the director of the Logan Park field house, the only year-round facility the park board operated.

Dietz needed very little time to establish her reputation at Logan Park. In an article on the opening of the 1920 summer playground season, the Minneapolis Tribune (June 20) commented that Dietz had already “taught the Logan Park neighborhood what a field house was really meant to be.” Apparently in the seven years between its construction in 1912 and Dietz’s arrival the field house had been less successful.

By the end of that summer the Tribune (October 17) provided an unusual glimpse of park life “in a community where there are a dozen nationalities struggling with the intricacies of life in a new country.” In that environment, the paper reported, Mrs. Dietz was trusted by “children and mothers alike.” As a result, Dietz was able to “buoy the self-confidence of the women who are awed by the greater facility of their children in the new tongue and to make the children realize what they owe to their parents.”

Among her responsibilities were teaching drama, dance and arts and craft classes, directing all athletic activities for girls, and putting on plays and pageants. The previous year she had also managed boys athletic activities developing “proficiency in boxing and football that surprised even herself” the Tribune reported. The paper continued that “almost to her regret,” a man had then been brought in to look after the boys and young men. In between all this she “listens to all the troubles that everybody tells her…and never turns a hair through it all.” The Tribune also praised the “Logan Park spirit” she had instilled noting that “the children have come to feel that the place belongs to them and they look over a newcomer with stern eyes. He has to measure up to what they think is proper Logan Park behavior.”

Dietz’s work with pageants and performances at Logan Park led to her being handed responsibility for the citywide playground pageants staged at Lyndale Park at the end of each summer.

The first playground pageant on the hill above the Rose Garden at Lyndale Park attracted a crowd estimated at 10,000. (1918 Annual Report, Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners)

The first two pageants, “Mother Goose” in 1918 and “The Pied Piper” in 1919, were directed by Julia Beckman, a teacher at North High School, but from 1920 Dietz wrote and directed the playground pageants as they became one of the highlights of the summer playground program. Children from every Minneapolis park were involved in creating costumes and props for the program. Up to 1,500 children appeared in the pageants each year which were staged on the hill overlooking the Rose Garden in Lyndale Park. The two-night performances were attended by up to 40,000 people. The popularity of the pageants caused the park board to consider more than once (first in 1930) the construction of an amphitheater on the site. Except for a brief hiatus during the Depression, the pageants continued through 1941. The pageant was incorporated into the Aquatennial in 1940, the first year of that celebration. With the ascendancy of the Aquatennial, and with the nation at war, the pageant was discontinued a year later.

The pageants were original scripts written by Dietz. While she created small roles in her pageants for park commissioners, she never allowed commissioners to have speaking parts. After her second pageant in 1921, “Weaver of Dreams,” Dietz asked the park board to allow her to retain copyright of the pageant scripts. The park board agreed that she could retain those copyrights as her personal property. (I have seen no indication that Dietz ever licensed those or subsequent scripts for performances by others.)

I recently found in a scrapbook kept by Victor Gallant evidence that Dietz had a background in theater as a performer before she worked for the park board. I had found an item in park board proceedings that Dietz requested a leave of absence for a week in the 1920s to attend a dance workshop in New York at her own expense, which was granted by the board. From that reference I knew Dietz had an interest in dance beyond the classes she taught at Logan Park and the dances she had incorporated into her pageant scripts. But the undated newspaper clip that appeared at the time of her 40th anniversary of employment with the park board (her last year), mentions her own theater performances as a girl.

![dietz 002[1]](https://minneapolisparkhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/dietz-0021.jpg?w=480&h=330)

Alice Dietz in 1957 near the time of her retirement and as a child actor, from an undated newspaper clip.

As the Director of Community Centers in Minneapolis parks, Dietz played a central role in the redefinition of recreation in the park context. The range of activities and classes offered at Logan Park was unprecedented in Minneapolis. In addition to expanding the range of activities provided for both children and adults, Dietz oversaw the conversion in 1922 of the large social room at Logan Park into a gymnasium for sports. The other recreation centers in Minneapolis at that time were little more than warming houses for skaters. They were later criticized by a national park expert as too big for warming houses and too small for anything else. (Weir Report, 1944.) Despite the phenomenal popularity of Logan Park under Dietz’s direction, the park board did not build another similar facility until the 1960s. Perhaps park commissioners feared that while they could replicate the field house they could not replicate Dietz.

Dietz’s role in the development of park programming in the 1920s at Logan Park was significant, but her greatest achievement may have been in training the army of recreation supervisors who worked in parks across the city in the 1930s. With the onset of the Depression in 1930 and the slashing of recreation budgets, Dietz lost her three assistants at Logan. Summer recreation positions in parks across the city were slashed from seventy-five to zero in 1933. When the American Legion tried to fill the void in eleven parks by providing volunteer supervisors, they were sent to Dietz for training.

That was just a glimmer of what would follow. For the 1934 playground season the Works Progress Administration inaugurated a recreation program that at its peak would place more than 240 recreation supervisors in Minneapolis parks and playgrounds. The WPA recreation program continued until 1943. During those ten years, thanks to federal and state work-relief programs, Minneapolis parks offered the most comprehensive, year-round recreation programming in the city’s history. The entire program, including the training of hundreds of new personnel, was coordinated by Alice Dietz from her office at Logan Park.

That experience served her and the city well after WWII when the park board was able to expand recreation programming and offer year-round activities at a handful of parks. Dietz was once again responsible for training the first generation of full-time, year-round recreation supervisors employed by the park board.

These are the outlines of Alice Dietz’s remarkable career in the recreation department of Minneapolis parks. I know little about Alice Dietz beyond what I have related here other than the fact that she was president of the Minnesota Recreation and Park Association in 1947. If you can tell us more about Dietz — or you have another person to nominate as a Minneapolis Park Hero — please comment here or contact me at the e-mail address below.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Minneapolis Park History Resources: Maps

If you love history, you probably love maps. For students of Minneapolis history, including the history of the park system, two of the most fascinating maps are found at the website of the John R. Borchert Map Library at the University of Minnesota. Have a look at the digitized 1892 Minneapolis plat book and the 1903 Minneapolis plat book. Compare them to the city map at right that Horace Cleveland used to illustrate his “suggestions” for the Minneapolis park system in 1883. Search for your home, park, church, school; see how your neighborhood was created or has changed.

While your at the Borchert Libreary site be sure to investigate the aerial photos. Many excellent images of Minneapolis as it’s grown.

Warning: you could spend hours with these maps and photos. For me, they have the addicting power of video games. But the things you’ll discover! Such as: H. W. S. Cleveland owned a half-block of land in south Minneapolis in 1892. I know! Nobody cares! But it’s endlessly interesting for those curious about their surroundings and the people who created them.

If you have a favorite research tool or resource, let us know. Especially if it’s accessible while in pajamas.

David C. Smith

Lost Minneapolis Parks: Virginia Triangle

Can you tell where this photo was taken? The land in the foreground is a lost Minneapolis park: Virginia Triangle.

Virginia Triangle was at the intersection of Hennepin and Lyndale avenues; the cross street is Groveland Avenue. Hennepin crosses left to right and Lyndale right to left. The photographer was facing north. That’s the Basilica straight ahead, St. Mark’s to the right, with the trees in Loring Park between them. To your immediate right (out of the picture) is Hennepin Avenue Methodist Church. On your left, just past the cross street, is Walker Art Center. Beyond that is The Parade, athletic fields when this picture was taken, but now the home of the Sculpture Garden.

Isn’t this view lovely compared to the freeway interchanges, tunnels, etc. of today? The park board put up and decorated a huge Christmas tree in the triangle each year. I don’t know when that practice began or ended, but I’ll try to find out. If you know, send me a note.

An important memorial was installed at Virginia Triangle in 1915. The park board did not pay for the memorial but agreed that it could be placed in the park triangle. Whose memorial was it? This photo was taken at the dedication. ( That’s Hennepin Methodist church across Lyndale Avenue in the background, Hennepin Avenue in foreground.)

He had something to do with urban transit and his mansion was immediately to the left of the photographer when this picture was taken. An avenue in north Minneapolis is named for him. He donated part of the land for The Parade and paid to have it developed into a park.

Here is his statue as part of the memorial that was put on the triangle.

This is what Rev. Dr. Marion Shutter said when he spoke to the crowd gathered at the dedication above:

How grandly has the sculptor done his work! This heroic figure needs no emblazoned name to identify the original. It seems almost as if Karl Bitter (the sculptor) had stood by the door of that little Greek temple at Lakewood (cemetery), and had said: ‘Thomas Lowry, come forth.’

Virginia Triangle was acquired by the Minneapolis park board on the first day of the last century. A.W. French and his wife donated the property to the park board in a swap. The Frenches had originally donated a piece of land for Hennepin Avenue Parkway, but apparently wanted that piece back and offered what became Virginia Triangle instead. The park board accepted on January 1, 1900. The best guess is that the name of the triangle comes from “Virginia Flats,” the apartment building behind the memorial in the photo above according to a 1903 plat map.

Thomas Lowry was joined on the triangle by another statue for a time during the summer of 1931. The Knights Templar held their conclave in Minneapolis that year and requested permission to erect life-sized statues of knights on horses throughout the city. The request was approved by the park board on the condition that all park properties be returned to their original condition without cost to the park board at the conclusion of the conclave.

The statue at Virginia Triangle was probably similar to this one placed at The Gateway during the conclave. Other statues were placed at The Parade and Lyndale Park.

Virginia Triangle was eventually lost to freeway construction when I-94 was built through the city. With freeway entrances and exits needed for Hennepin and Lyndale, the triangle had to be removed even though the freeway itself was put underground below Lowry Hill and Virginia Triangle.

The state highway department paid the park board $24,300 for the triangle in 1966, plus the actual cost of relocating the Lowry Memorial. The park board chose another triangle about a half-mile south on Hennepin Avenue at 24th Street as the new site for Thomas Lowry. The low bid for moving the memorial to the new site at Smith Triangle in 1967 was $38,880.

The inscription on Lowry’s memorial reads:

Be this community strong and enduring — it will do homage to the men who guided its youth.

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Elusive Minneapolis Ski Jumps: Keegan’s Lake, Mount Pilgrim and Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park

The Norwegians of Minneapolis had greater success getting their music recognized in a Minneapolis park than they did their sport. A statue of violinist and composer Ole Bull was erected in Loring Park in 1897.

This statue of Norwegian violinist and composer Ole Bull was placed in Loring Park in 1897, shown here about 1900 (Minnesota Historical Society)

A ski jump was located in a Minneapolis park only when the park board expanded Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park in 1909 by buying the land on which a ski jump had already been built by a private skiing club. The photo and caption below are as they appear in the annual report of the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners for 1911.* While the park board included these photos in its annual report, they are a bit misleading. Park board records indicate that it didn’t really begin to support skiing in parks until 1920 — 35 years after the first ski clubs were created in the city.

Minneapolis, the American city with the largest population of Scandinavians, was not a leader in adopting or promoting the ski running and ski jumping that originated in that part of the world. Skiing had been around for millenia, but it had been transformed into sport only in the mid-1800s, around the time Minneapolis was founded. Ski competitions then included only cross-country skiing, often called ski running, and ski jumping — the Nordic combined of today’s Winter Olympics. Alpine or downhill skiing didn’t become a sport until the 1900s. Even the first Winter Olympics at Chamonix, France in 1924 included only Nordic events and — duh! — Norway won 11 of 12 gold medals.

The first mention of skiing in Minneapolis I can find is a brief article in the Minneapolis Tribune of February 4, 1886 about a Minneapolis Ski Club, which, the paper claimed, had been organized by “Christian Ilstrup two years ago.” That article said the club “is still flourishing.” Eight days later the Tribune noted that the Scandinavian Turn and Ski Club was holding its final meeting of the year. The two clubs may have been the same.

Ilstrup was one of the organizers two years later of one of the first skiing competitions recorded in Minneapolis, which was described by the Tribune, January 29, 1888, in glowing and self-congratulatory terms.

Tomorrow will witness the greatest ski contest that ever took place in this country. For several years our Norwegian cultivators of the noble ski-sport have worked assiduously to introduce their favorite sport in this country, but their efforts although crowned with success, did not experience a real boom until the Tribune interested itself in the matter and gave the boys a lift.

The Tribune mentioned the participation in the competition of the Norwegian Turn and Ski Club, “Vikings club” and “Der Norske Twin Forening.” The Tribune estimated that 3,000 spectators watched the competition held on the back of Kenwood Hill facing the St. Louis Railroad yard. Every tree had a dozen or so men and boys clinging to the branches, while others found that perches on freight cars in the rail yard provided the best vantage point.

The caption for this photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Visual Resource Database claims the photo is from the winter of 1887, but was almost certainly taken at the ski tournament held on Kenwood Hill late that winter in February, 1888.

The competition consisted of skiers taking turns speeding downhill and soaring off a jump or “bump” made of snow on the hill. Points were awarded for distance and for style points from judges.

The winners of the competition were reported as M. Himmelsvedt, St. Croix Falls, whose best jump was 72 feet, and 14-year-old crowd favorite Oscar Arntson, Red Wing, who didn’t jump nearly as far, but jumped three times without falling. Red Wing was a hot bed of ski-jumping, along with Duluth and towns on the Iron Range. (The winner was perhaps Mikkjel Hemmestveit, who along with his brother, Torger, came from Norway to manufacture skis using highly desirable U.S. hickory. The Hemmestveit brothers are usually associated with Red Wing skiing, however, not St. Croix Falls.)

A Rocky Start

Despite the enthusiasm of the Tribune and the crowds, skiing then disappeared from the pages of the Tribune until 1891, when on March 2, the paper reported on a gathering of thirty members of the Minneapolis Ski Club at Prospect (Farview) Park. “This form of amusement is as distinctively Scandinavian as lutefisk, groet, kringles and shingle bread,” the Tribune reported. “With skis on his feet a man can skim swiftly over the soft snow in level places, and when a slope is convenient the sport resembles coasting in a wildly exhilarating and exciting form,” the report continued. The article also described the practice of building snow jumps on the hill, noting that “one or two of the contestants were skilful enough to retain their equilibrium on reaching terra firma again, and slid on to the end of the course, arousing the wildest enthusiasm.”

The enthusiasm didn’t last once again. The Tribune’s next coverage of skiing appeared nearly eight years later — but it came with an explanation:

During recent winters snow has been a rather scarce article. A few flakes, now and then, have made strenuous efforts to organize a storm, but generally the effort has proven a failure. The heavy snow of yesterday was so unusual that it is hardly to be wondered at that there arose in the breasts of local descendants of the Viking race a longing for the old national pastime, skiing…The sport of skiing was fostered to a considerable extent in the Northwest, and particularly in this city, a few years ago, but the snow famine of late winters put a damper on it.

— Minneapolis Tribune, November 11, 1898

The paper further reported that the “storm of yesterday had a revivifying effect upon the number of enthusiasts” and that the persistent Christian Ilstrup of the Minneapolis Ski Club was arranging a skiing outing on the hills near the “Washburn home” (presumably the orphanage at 50th and Nicollet). The paper also reported that while promoters of the club were Norwegian-Americans, “they do not propose to be clannish in the matter.”

Within a week of that first friendly ski, Read more »

This is why we love our parks: Powderhorn Art Sled Rally

Creative use of space. It is the true gift of parks. If anyone ever needed convincing of the incredible benefits of public spaces, they should have been at Powderhorn Park yesterday for the 4th Annual Art Sled Rally. Thrills, chills and plenty of spills. Marvelous creativity. Wacky fun. It’s what a creative community can do when it has a place to do it.

Cheers to South Sixteenth Hijinks for the idea and energy. Be sure to click the link above to learn more about the event and organizers. Especially check out the sponsors and please support them.

I didn’t see all the sleds, but among my favorites were the bear from Puppet Farm, (picture a bear sliding on its stomach, and, yes, there was a child seated on top of the bear sled, too) and a wild dinner table on a sled, which I believe was called “Dinner at the Carlisle’s.” Other favorites were a couple of dragons, a dragon fly, a bunch of eyeballs and a London Bridge, which did indeed fall down. Some pictures are already posted on artsledrally.com from Dan Stedman. I hope others will soon follow.

The greatest tribute to the event and the people who made it happen: as we walked away my daughter asked, “Can we make a sled next year?”

David C. Smith

New Rodents at the U: Beavers, not Gophers

Beavers invade Minneapolis park near University of Minnesota!

That’s the gist of my favorite, undated newspaper clip from Victor Gallant’s scrapbook: Minneapolis Parks, 1923-1949. The article had to be from the late 1940s, I’ll tell you why in a moment.

Here’s the story. Three beavers have moved into the east river flats below the U. Need proof? They’ve been felling cottonwood trees along the river bank. Two dozen of them! (Cottonwoods are nobody’s favorite tree, in fact the park board once considered banning the planting of them in the city, but they do spring up on river banks and provide greenery and shade that is flood tolerant.)

The newspaper reports that the beavers are living under a sunken houseboat along the river bank. Park superintendent Charles Doell asks the game warden to remove the beavers so they don’t cut down more trees. (Seems to me it would have been smarter to remove the sunken houseboat to eliminate the avant garde urban beaver habitat.) But Dr. W. J. Breckenridge of the University’s Museum of Natural History points out the advantages of having a living natural history exhibit virtually on campus. Doell relents and instead of evicting Goldy’s cousins, he has a couple loads of poplar trees delivered to the riverbank so the beavers have something to eat other than living cottonwoods. It is believed that the beavers immigrated from known colonies on the Mississippi River at Dayton and Anoka. (Did they come over the falls or through the mill races?)

Big Yellow Taxi

That’s the first and last I’ve heard of beavers in Minneapolis. I suspect they didn’t stay long. I’m pretty sure that the article appeared between 1945 and 1949. It had to be after Doell became Superintendent in 1945 and before Gallant quit keeping the scrapbook in 1949. But I didn’t need to know that was the end of Gallant’s newspaper clipping to figure out that date, because it was in 1949 that the University and park board signed a ten-year agreement for the U to use the river flats as a parking lot. I’m guessing that the beavers wouldn’t have settled next to a busy parking lot. And if they had, everyone would have been happy to evict them if their gnawing was endangering cars instead of just trees. Nobody wants a cottonwood in their back seat, even if its young.

The U’s lease of the parking lot kept being extended beyond the original ten-year term. The park board didn’t take back the land for a park until 1976! Some cottonwood trees only live about as long as that lease lasted.

Do you know the official name of the park where the rodents lived for a while? It rhymes with beavers.

In 1894 the park board named the east river flats “Cheever’s Landing,” after the man who operated a ferry across the river there. I don’t believe the name ever has been changed officially.

And speaking of wildlife and the James Ford Bell Musuem of Natural History at the University of Minnesota, the coolest sculpture in the city is the wolf pack attacking a moose near the entrance to that museum. Worth a visit. Don’t jump when you see them.

A partial view of the sculpture by Ian Dudley outside the James Ford Bell Museum of Natural History at the University of Minnesota (Photo: Tara C. Patty)

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

Powderhorn Park Speed Skating Track: Best Ice in the United States

Many years before Frank Zamboni invented his ice resurfacer (in California!?), Minneapolis park board personnel had to prepare the speed skating track at Powderhorn Park mostly by hand for international competition and Olympic trials. They were very good at it.

Olympic medalist speed skater Leo Friesinger from Chicago (whom you already met in these pages here) had this to say after he won the Governor Stassen trophy as the 10,000 Lakes senior men’s champion in the early 1940s:

“It is a pleasure for me to return to Minneapolis and skate on the best ice in the United States.”

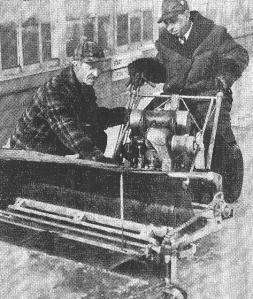

That was high praise for Elmer Anderson and Gotfred Lundgren, the park board employees who maintained the track at Powderhorn using this sweeper, a tractor-drawn ice planer and a bucket of warm water.

The ice sweeper that cleaned the Powderhorn speed skating track in the 1940s. Elmer Anderson (left) and Gotfred Lundgren kept the track in top shape.

They began to prepare the track 3-4 days before a meet by sprinkling it with water a few times. Then they’d pull out a tractor and a plane—a 36-inch blade—to smooth out any bumps from uneven freezing. The biggest problem was cracks in the ice. So the day before the race, Elmer and Gotfred would spend 8-10 hours filling small cracks by pouring warm water into them.

At times their crack-filling work continued right through the races. When large crowds showed up, and for some races attendance surpassed 20,000, the ice tended to crack more often. If Elmer or Gotfred spotted a crack during a race they’d hustle out with a bucket of water after skaters passed and try to patch it. The sweeper was used to remove light snow from the track.

Elmer and Gotfred, who began working for the park board on the same day 18 years before this picture was taken, agreed that the most speed skating records were set when the air temperature was about 30 degrees, which raised a “sweat” on the ice and produced maxiumum speed.

(Source: an undated newspaper clip in a scrapbook kept by Victor Gallant, the park keeper for many years at Kenwood Park, Kenwood Parkway and Bryn Mawr Meadows.)

It’s no wonder that speed skating (as well as hockey) eventually moved indoors to temperature-controlled arenas. But wouldn’t it be fun to see a big race at Powderhorn again?

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith

And the answer is….French

In a post on December 29, 2010 I asked how these two pictures were related to the creation of Minneapolis parks.

Nobody has come up with the right obscure answer! So I’ll tell you.

The photos are of the most famous works of American sculptor Daniel Chester French. (The best example of French’s work in Minneapolis is the statue of John Pillsbury at the University of Minnesota.)

Here is the connection — and the key word is “related”:

Daniel Chester French’s older brother was William Merchant Richardson French. That’s this guy:

(Their father was Henry Flagg French who was the number two man in the U. S. Treasury Department. For eight months in 1881 he worked under Secretary of the Treasury William Windom, a U. S. Senator from Minnesota who resigned his Senate seat to become Treasury Secretary for President James Garfield. After those eight months, Windom resigned at Treasury and was elected to fill his own open seat in the Senate. He served as Secretary of the Treasury again from 1888 until his death in 1891.)

The important connection of William French to Minneapolis parks is that after graduating from Harvard in 1864 and a year at MIT studying engineering he moved to Chicago and met a man in the new and unusual profession of landscape gardening. It’s not clear how it came about, but in 1870 William French became the partner of a man thirty years older than he was. That pioneering landscape architect was Horace Cleveland.

Of course, young William, who was eager I’m sure to earn his keep with his much more experienced partner, went through his list of connections to identify potential clients. He likely recognized that one name on his list might provide useful contacts in a young city west of Chicago, Minneapolis. That contact was his cousin, George Leonard Chase, who was rector at the episcopal church in the small town of St. Anthony, which was springing up beside the falls of that name. Now it just happened that Chase had married one of the Heywood girls, Mary. And that was a funny thing because Chase’s best friend married Sarah Heywood, Mary’s sister. He and his best friend had lived together while they were students at Hobart College in New York. In fact, Chase had apparently had some influence with the regents of the University of Minnesota when they were hiring the university’s first president in 1869. Chase’s friend and brother-in-law by marriage was hired for that job. His name was William Watts Folwell.

Comments (4)

Comments (4)