Archive for the ‘Minneapolis Park Board’ Category

Minneapolis Elections: All the Results

I was recently asked about a website that provided complete election results for Minneapolis city offices from City Council to Park Board, Library board and more. I first mentioned it in a post in 2011 and it’s bigger and better than ever.

It’s Minnesota Election Trends Project, which was created by Neal Baxter in 2004. For political geeks and policy wonks, it’s priceless. You can find not only fascinating anecdotes about city elections but a list of every elected official and the results of every city referendum since “Mni” and “polis” were mashed together. The site has also expanded to cover elections in more municipalities in the state.

The site might be a good place to start if you’re curious about past park commissioners and their roles in the issues addressed in my last post. What did they stand for? What motivated them? The site will have all the names to get you started. If you find something interesting, send it to me as a comment here.

Even if you aren’t interested in historical research but have already finished the NYT crossword and don’t have the stomach for more doomscrolling, take a look.

David Carpentier Smith

The Minneapolis Park Board Has Never Been and Shouldn’t Be the Deed Police

Horrors! The Minneapolis Park Board bought 49 acres of land near Lake Hiawatha and Minnehaha Parkway for $1. How dare they? They should have known the donor, er… seller, was a real estate developer who inserted racial covenants on the deeds to the surrounding property that prohibited ownership or occupancy by non-whites. Let’s cancel that sale from 100 years ago!

I recently wrote a letter to the editor of the Minnesota StarTribune, published November 29, in which I praised the Mapping Prejudice Project which identifies racial covenants in property deeds. The project has examined property deeds in Hennepin County to identify those that contain racial covenants inserted between 1910 and 1955. The covenants prohibited ownership or even residence by Black people on those properties. The project identified more than 8,000 racial covenants in Minneapolis deeds and three times that many in suburban Hennepin County.

Writing racial covenants in deeds was a deplorable practice, especially by the developers and realtors who created those covenants, and deserves to be exposed. They should be called out and held to account. If their heirs or successors have an explanation, let’s hear it. I urged caution, however, in what we attribute to those covenants.

I am writing today to explain in greater length than an editorial page in a newspaper permits why I objected to some claims in the StarTribune column and in the sources cited in that piece.

I took issue with a column “The link between racial covenants and the development of Minneapolis parks” in the November 16 paper that argued “agreements between land developers and the Minneapolis Park Board created a network of exclusive whites-only neighborhoods with ample public land.” I saw no evidence in the column that supported the claim that the park board agreed with anyone to create such neighborhoods. I don’t believe there is any evidence, at least I haven’t seen any. The acceptance of free or cheap land for parks proves nothing.

The claim in the StarTribune column was based in part on a deceptive graphic presentation on the Mapping Prejudice website entitled “Greenspace, White Space: Real estate, racial segregation, and the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.” Much of the same material is presented in articles at Landscape and Urban Planning and Annals of the American Association of Geographers.

In those pieces the authors justly castigate realtors and developers, particularly Edmund Walton and Samuel Thorpe, for promoting whites-only enclaves. Walton and the company he created, led by Henry Scott after Walton’s death in 1919, was responsible for racial covenants primarily in developments near Cedar Lake and in the Longfellow neighborhood near West River Parkway. Thorpe promoted racial exclusivity in his projects across southern Minneapolis, especially in Shenandoah Terrace just north of Minnehaha Creek between Chicago Avenue and 12th Avenue South, and even more prominently in Edina, most notably in the Country Club neighborhood.

As I pointed out in my letter to the StarTribune, however, “Throughout the period when racial covenants were used by some developers and realtors, the park board was acquiring land for parks wherever it could as cheaply as possible — as it always had done.”

The Context

From the creation of the park board in 1883, park commissioners tried to preserve open spaces and features of the landscape that were then considered especially attractive and worthy of preservation. They were also trying to locate parks in every neighborhood in the city, another laudable goal. Should they have ignored neighborhoods with some houses built or sold by racists? What would the city look like now if the park board had exercised such discrimination then?

Free or nearly free parkland helped make Minneapolis the city it is today, with ample open space for anyone who chooses to live here. Much of Minneapolis’s waterfront — creeks, lakes, and river — for instance, was donated or bought very cheaply for parks. The same is true for parts of the celebrated Grand Rounds, the parkways for pedestrians, bicycles, and cars that nearly encircle the city. No doubt some donors hoped the creation of parks would make their other land in the vicinity more valuable. But whether it did or not was beyond the park board’s mission. The park board was created to provide parks throughout the city, not police real estate transactions. The demand for parks was great, the supply of money to buy them wasn’t.

Park proponents at the time certainly argued that the creation of parks would increase the value of surrounding land, which would in time pay for the acquisition through higher property tax receipts. It was no secret that people would want to live near a park and would pay more to do so. Nothing nefarious about it. Supply and demand. Better views, it has been said, are one of the only things that money can buy. And land speculation in Minneapolis was rampant in the 19th and early 20th Century — with or without parks.

It was widely understood when the park board was created that the acquisition in the 1850s of the country’s most famous urban park, Central Park in New York, had increased surrounding property values so much that property tax revenue did pay for the park. The challenge for a younger city like Minneapolis was to acquire land for parks before it got too expensive, but also to provide parks near where people lived. Naturally, that meant acquiring land near more crowded neighborhoods first, which the park board did in the twenty-seven years before the first deed with a racial covenant. And they did so for the most part, Logan Park was an exception, without taking people’s homes.

Did some speculators or investors make money from giving land to the park board? Without a doubt — likely including some park commissioners, some of whom were in the real estate business. But did we all get a more livable city in return? I think we did. Should we care if someone made a few bucks by giving most of Lake Harriet, the Mississippi River banks, Minnehaha Creek, or many other acres of land to the people of Minneapolis, to us? More than 100 years later, we collectively still own that land and we get to argue over how to use it even as the city has become dramatically more diverse over the last century.

Admirable Objective

The exposure of racial covenants (some covenants in the 1910s also banned sale to Jews) takes on added importance today as some people insist on white-washing American history, refusing to acknowledge anything that is less than admirable in our nation’s past.

That effort is sad especially because what is most laudable in our history are efforts to overcome the errors, to correct the mistakes, to right the wrongs of those who came before us while maintaining the best of what they imagined.

The continuing struggle to expand their vision and ensure rights for all people, to bring “all are created equal” into the present day where it applies to every man, woman and child regardless of differences is what we should be most proud of. How can we be proud of that fight and the progress we have made if we can’t admit why the battles had to be fought. And still need fighting.

I appreciate that the intentions of the authors of pieces with which I disagree in part likely have the objective of getting us to match our actions with our lofty words. But the demand to acknowledge history, even its shameful moments, requires us to assess with clear eyes and some depth of understanding, context, and nuance the events of the past. I believe claims such as those made in the StarTribune, as well as some on Mapping Prejudice’s own website, fail that test.

A Fuller Picture

Mapping Prejudice identified more than 8,000 deeds in Minneapolis that contained racial covenants. What the project doesn’t tell us is what percentage of deeds that represents. A square mile in the most “gridlike” residential neighborhoods in north and south Minneapolis hold over 3,000 parcels of land. (That’s 8 blocks north-south by 16 blocks east-west, assuming 24-30 lots per block.) Minneapolis’s total land area is about 54 square miles. I won’t attempt to guess how much of that land is categorized as residential for the purposes of the mapping endeavor.

Complicating the calculations is that, to my eye (I haven’t counted), in the map that Mapping Prejudice has published it appears that perhaps nearly half of the covenanted deeds within Minneapolis city limits are located south of 54th Street on the southern border of the city. That’s an issue because the section of Minneapolis from 54th Street to 62nd Street (roughly the Crosstown Highway) was annexed from Richfield in 1927. A random sampling of the properties that had racial covenants in those areas suggest that many of them predated the annexation, which hardly implicates the Minneapolis Park Board in colluding to favor whites-only neighborhoods. Perhaps Mapping Prejudice has a breakdown of those numbers; it would be useful. If my observations are accurate, that would reduce the share of covenanted deeds in the rest of the city, perhaps considerably.

While even one racial covenant is deplorable, their frequency may be useful in understanding the scope of the problem, particularly when indicting decades of park planning and acquisition as racist or claiming problems are or were systemic or structural. The question “How common?” matters because it gets to the issue of whether people cherry-pick data to buttress an argument. Is confirmation bias at work? Are researchers looking only for data or anecdotes that confirm their biases and ignoring what doesn’t?

These are my biases: I admire the efforts and foresight of park proponents over a century-and-a-half who helped to create a park system that makes life better in this city; I believe their overall contributions to our lives are praiseworthy; I don’t believe all of them were greedy profiteers; I believe they could have done some things better. I try not to let those biases interfere with my writing about parks, but they may creep in.

The StarTribune column and Mapping Prejudice site claim that “three-fourths” of the parks created between 1910 and 1955, were in neighborhoods with racial covenants. The parameter they establish is a park within a half mile of a property with a racial covenant in the deed is in what they call a racial-covenant neighborhood. A racial covenant anywhere within a square mile around a park, therefore, would doom that park to the scorned heap of parks allegedly created to entrench white supremacy — or provide green space exclusively for white people.

By that measure, one per square mile, just 54 racial covenants could be enough to condemn every park in Minneapolis. What lends a bit of irony to the “half mile” measure is that the park boards of that time were trying to meet a goal of having a neighborhood park within a half mile of every residence in the city because a half mile was judged about the farthest a mother could walk with two young children to play in a park. (Yes, it was a different time.) There was no effort to determine if that hypothetical mother of two was worthy of having a park to walk to.

In the two journal articles I cited, the authors use a different measure of racially restricted neighborhoods. Those studies define a “racial covenant neighborhood” as one in which one property within roughly a city block (0.1 mi.) has a racial covenant in a deed. If one racist nut lived near a park and put a covenant in their deed does that mean the park board entered into “agreements” to create green space for exclusively white neighborhoods? And that park would get lumped together with any other park with a racist nut within a stone’s throw of it (if it were Shohei Ohtani making the throw).

To adjust for the narrower definition of a racial covenant neighborhood in the journal articles, the authors opt for a different claim: not that three-fourths of new parks were in such a neighborhood, but three-fourths of new park acreage was in a “racial covenant neighborhood.” A big difference, but equally misleading.

The journal article cited in the StarTribune column claims that park acreage acquired within city limits in the racial covenant years was 1,163 acres of which 846 were in a “racial covenant neighborhood.” Those numbers overstate the impact of large acquisitions like 234 acres at Lake Hiawatha, which was abutted at the time of acquisition on the southeast corner by a Thorpe Realty development that included racial covenants.

Samuel Thorpe’s company began development of that property after the park board had already spent considerable effort defining the shores of nearby Lake Nokomis. The park board had dredged the lake to make it deeper and to fill the lowland around the lake to make it usable as recreation space. (MaryLynn Pulscher’s description is “land dry enough to drive on and water deep enough to sail on.”) The park board waited years for that muck to dry and settle before creating playing fields, a beach and parkway west of the lake. That’s when Thorpe sold the park board 49 acres of land to the east along Minnehaha Creek for a buck.

The change in measurement from the number of parks to park acreage maintains the appearance of racist acquisition even as the definition of a racial covenant neighborhood is narrowed to a less ludicrous distance than half a mile. Because by the measure of a covenant within a city block of a park, the park board created many more parks in those 45 years in neighborhoods that were not racially restricted than those that were. So we get park acreage as a measure instead, which looks worse — but on closer examination doesn’t hold up either.

To understand the distortion of the acreage measurement, compare Lake Hiawatha’s 234 acres, for instance, with Sumner Park, a 4.5-acre park in north Minneapolis that was acquired in 1915 at the request of Associated Jewish Charities. Sumner was not in a racial covenant neighborhood. It would take more than 50 Sumners to balance one Lake Hiawatha by the acreage measure cited. And the park board couldn’t have created fifty Sumner Parks without knocking down considerable existing housing around the city, which it didn’t have to do at Lake Hiawatha.

The Lake Hiawatha land was acquired in 1922 for the specific purpose of creating a golf course in south Minneapolis. It was one of the only undeveloped sites in the southern half of the city that was big enough for a golf course, and as a wetland it wasn’t good for much else in the eyes of urban residents 100 years ago, and therefore more affordable. (For more on the acquisition of Minnehaha Creek see Accept When Offered: A Brief History of Minnehaha Parkway.) North Minneapolis already had two popular golf courses, Wirth and Columbia, and Gross and Meadowbrook would be added before the course at Hiawatha was completed nine years later, so the park board was eager to extend what many residents considered a benefit to the southern half of the city.

Different land-use choices might be made today than in the 1920s, but to attribute racist motives to creating that park and lake is a stretch. Ironically, for those of the racist-park-board ideology, that golf course became a favorite of Black golfers in the city. And the land is currently being considered for a major overhaul to meet contemporary demands — which of course wouldn’t be possible if the land weren’t already owned by us.

It’s also worth noting that in the 1920s the park board also acquired all of Minnehaha Creek west of Lake Harriet to ensure the people of Minneapolis, us again, owned the entire creek bed from Edina to the Mississippi River. That acquisition of nearly 1.5 miles of creek was tainted too by the racial-covenant measure, primarily by 16 lots south of the creek in the 5200 block between Morgan and Logan Avenues. The covenants were in deeds granted by Thomas J. Magee who apparently subdivided that block in the late 1920s. That cluster and one lot across the creek contain the only creek-adjacent lots with racial covenants for the approximately three miles of creek from Edina to Portland Avenue.

Another case is St. Anthony Parkway from the Mississippi River to the eastern border of Minneapolis, including Deming Heights. That parkway’s 103 acres are tainted by a couple dozen lots with racial covenants on its far eastern end three miles of parkway from the river. Those covenants did not exist when the parkway was created and the park board never exercised any control over those lots. Nor should it have, in my view.

More acreage. Shingle Creek Parkway and Creekview Park, nearly sixty acres in north Minneapolis with covenanted property (developed by Girard Investment Company) only on its southern end near Webber Park. The park board reluctantly acquired the land in 1948 during the post-war housing boom only at the insistence of the City of Minneapolis. The city wanted the park board to acquire Shingle Creek and lower the bed of the creek to help drain the surrounding wet neighborhood so more housing could be built there as the city was bursting its seams. Very few new lots developed on either side of the creek carried racial covenants.

There were, however, racial covenants on deeds on the east side of nearby Bohannon Park which was deeded to the park board in 1935 by the city after it closed the workhouse on that site. A free park. Again, no signs of collaboration with racist developers to create whites-only neighborhoods, just another inexpensive neighborhood park for the majority of families whose property deeds did not contain racial covenants.

There were many more reasons for the park board to acquire park land than creating white enclaves. As the city’s population soared past 500,000 in the 1940s and housing was being built out to the city limits, the park board found a new method of acquiring land for parks: scouring the State of Minnesota’s list of land forfeited by delinquent taxpayers. Keep in mind that this followed nearly two decades of painful depression and then World War II. Nearly free land from the state list helped acquire all or portions of Bossen, Perkins Hill, Northeast, McRae, Hi-View and Peavey Parks. Both Bossen’s forty acres and McRae’s eight were supposedly tainted by racial covenants in the neighborhood.

The land between Bossen and Lake Nokomis to the northwest has one of the greatest concentrations of racial covenants in the city and once again some of those covenants predate the annexation of that land by Minneapolis. (A sampling of those properties finds four “grantors” names repeated many times: George and Sophia Pahl, Fred and Mabel Genevieve Cummings, Martin and Annie Nelson, and Arne G. and Sigrid Bogen. The A.G. Bogen Company also developed much of the land east of Pearl Park and Diamond Lake and recorded nearly 300 lots with racial covenants there.) On the other side of Bossen Field from those developments, however, the land north and east of the park all the way to Minnehaha Park is largely free of racial covenants; there are 24 parcels with racial covenants in 1.3 square miles. Most of them written by two couples, the Addys (7) and the Bogens (9).

As for McRae Park, reportedly a garbage site when acquired, whether it was imagined as green space for white people or not, it became a vital amenity serving Black neighbors too, as is evident from photos I posted several years ago here. (Be sure to read the comments, too.)

Schools and Playgrounds

Another way to reduce the cost of parks and maximize their usage, long championed by some park commissioners, was working with the school board to develop a park and school together. That was done in former Richfield locations at Armatage and Kenny in the late 1940s and early 1950s where many nearby lots had racial covenants, an undetermined portion of them also dating prior to becoming part of Minneapolis. The park board and school board also collaborated at Keewaydin and Hiawatha schools, and at Holmes Park and Cleveland Park to create playgrounds for schools, none of which were in racial covenant neighborhoods.

Another joint school/park project was at Waite Park in the northeast corner of the city. A housing development by Dickenson and Gillespie, Inc. north and east of the school and park attached racial covenants to deeds in 1947, a few months after the park and school boards acquired land. (The same outfit sold properties with racial covenants along Lake Nokomis Parkway west of the lake.) South and west of Waite Park there is not another property in all northeast Minneapolis, more than six square miles, with a racial covenant according to the Mapping Prejudice map. Should the park board not have collaborated with the school board to develop the Waite Park property, partly as a school playground, because of the covenants put on adjacent property?

In none of those locations, however, except perhaps Kenny Park, did the parcels with racial covenants outnumber those without racial covenants. Did the owners of those parcels not deserve schools or playgrounds because some other lots carried racial covenants? Should the park board have been deed police before or after it acquired land?

There is also the question of individual knowledge or acceptance of those perfidious covenants. I learned from a friend whose father died recently that when he went to sell the old family home he discovered that the deed included a racial covenant. He was appalled and quickly had that covenant removed from the deed. Little did he know or imagine that he grew up in a home that by itself could have damned the entire neighborhood as a “racial covenant neighborhood” according to some measures.

Was his father a racist? He didn’t think so. Were his neighbors? Who knows? Racists live among us. People who can’t accept differences live among us. People who want to paint everyone with broad brush strokes live among us too — as some are wont to do with park commissioners of a century ago.

Were some of those park commissioners racist? I would expect that some were. The challenge is to identify them. It’s easy to claim “institutional” racism because it absolves everyone, both accuser and accused. If injustices are “institutional” both everyone and no one is guilty, depending on the whims of the accusers and accused. It makes for lazy history.

In addition to accepting free or nearly free land for parks that are part of the alleged green space for whites only, the park board also accepted free or mostly free land during those years for Dorilus Morrison Park (the site of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts), Clinton Field, Stewart Park, Cedar Avenue Field, and Currie Park.

Disproportionate Claims

One entry on the Mapping Prejudice site claims: “Park acquisitions during this era were disproportionately in south Minneapolis, particularly along Minnehaha Creek, in the Nokomis neighborhood, and in the neighborhoods along the west bank of the Mississippi, parts of the city most densely blanketed with covenants.”

That is simply not true. Disproportionately? Compared to what? Minnehaha Creek I’ve already mentioned. In the area along the west bank of the Mississippi (the west riverbanks were acquired in 1902 after decades of trying) where Edmund Walton’s Seven Oaks Company inserted racial covenants in some the city’s highest concentrations, the park board made only three acquisitions in the 45 years that racial covenants existed: Brackett Park, Longfellow Park, and Seven Oaks Oval.

Seven Oaks Oval, which the developer gave to the park board, is a sink hole of two acres that has never been developed and probably didn’t attract many buyers to the neighborhood. It is shown as platted as a park in a 1903 map, long before racial covenants. As I have noted elsewhere, the park board has probably spent less money on Seven Oaks than any other park in the city.

Longfellow Park was a replacement for a park that was sold to the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company in 1917 during World War I (read more here) as the neighborhood became more industrial and after the school board had closed the adjacent Longfellow School. The new site was as close as the park board could come to replacing the surrendered land near East 28th Street and Minnehaha Avenue. It was on two undeveloped blocks that contained no houses in a thinly settled section of the city. The park board considered adding a third block, but because three houses had already been built on that block it’s assessed valuation was too high for the park board’s budget.

Brackett Field was in a section of the city that had some covenanted lots (a minority of property in the neighborhood, however) deeded mostly by Mary Greer east of the park and the Seven Oaks Company south and west of the park. A few lots with covenants were sold before the park was acquired but most were sold after park acquisition.

The park board acquired land on the margins of the city precisely because that’s where the city was growing and those sections did not have playgrounds yet. Minneapolis was overflowing and neighborhoods were expanding onto the last unbuilt land. The population of Minneapolis grew from 301,408 in 1910 to 521,718 in 1950. By contrast, the most populous suburb in 1950 was St. Louis Park at 22,644, triple what it was only a decade earlier. Minneapolis’s Black population increased from 2,592 in 1910 to 6,807 in 1950, or from 0.9% to 1.3% of the total population. (In 2020, 18.9% of Minneapolis’s population was Black.)

Not Much Happened for Nearly Two Decades

I noted earlier that the park board acquired some tax-forfeited land in the 1940s following the Great Depression and World War II. When considering the relationship of parks and racial covenants it’s worth noting that from the beginning of the Depression in 1929 until well after the war in the Pacific finally ended, the park board acquired very little land and didn’t pay for most of it. From 1930 until 1947, the park board added only six parks: Hiawatha School Playground was acquired from the school board; Bohannon Park was turned over by the city; the swamp of Todd Park was donated by the developer; Northeast Park was acquired largely through tax forfeiture; and Currie Park was purchased mostly with a cash donation for that purpose. The only acquisition the park board paid for was part of Bassett’s Creek Park, and that purchase in 1934 was to take advantage of a donation of thirteen acres of Bassett’s Creek a few years earlier by Arthur Fruen, a former park commissioner, adjacent to the mill he owned. The acquisition connected Bryn Mawr Meadows Park to Theodore Wirth Park (still named Glenwood Park then) along Bassett’s Creek and gave the park board ownership of all of that creek within city limits that’s above ground. {Read more about Bassett’s Creek here.)

By the “racial covenant neighborhood” measurement, two lots with racial covenants in their deeds a block west of Bassett’s Creek Park in the Bryn Mawr neighborhood, executed three and four years after the park was acquired in 1934, condemned all 60 acres of that park to the list of parks allegedly created for exclusively white neighborhoods.

The “racial covenant neighborhood” status of Bryn Mawr Meadows, which was acquired in 1910 isn’t quite clear as the western tip of that fifty-acre park is about 500 feet, just under a tenth of a mile, from the eastern tip of one lot in a development of about 60 lots west of Penn Avenue that Frank M. Groves and Hazel O. Groves attached racial covenants to 28 years later — not really a good example of the park board creating green space for a white enclave but perhaps classified as such for arguments sake.

Park acquisition isn’t the only thing that ground to a halt through part of the 1930s and 1940s. Especially during the war, there was almost no new residential construction. Both labor and materials for building were scarce. The result was a pent-up demand after the war for houses, schools and parks which led in part to the park and school collaborations in the late 1940s in the far south and north of the city.

Further complicating analysis of park acquisition during the time of racial covenants was a state law called the Elwell Law which permitted the park board to assess neighborhood property for the cost of acquiring and developing parks, if the neighborhood agreed to those assessments.

At the time it was viewed as a way to put decision-making in the hands of the people. In retrospect, however, it became evident that this method of park acquisition favored newer neighborhoods, wealthier neighborhoods, and neighborhoods with more single-family homes where people could afford assessments or where a park would increase the value of their property. Landlords of multi-unit buildings were not so keen to have a park developed nearby and have their costs increased.

Racial covenants on deeds did not always predict homeowners’ willingness to be assessed for parks, however. An example is the neighborhood around Kenny Park, part of the land annexed from Richfield, where many deeds contained racial covenants. That neighborhood declined to be assessed for a park in 1932, which delayed land acquisition as a joint project with the school board until 1948 and delayed any improvements until 1953.

From that perspective it doesn’t look like the park board provided an “exclusive whites-only neighborhoods with ample public land.” The people who bought property with racial covenants in the late 1920s had to wait more than two decades to get the parks the park board allegedly agreed to provide for their segregated neighborhood.

The park board formally ended the use of the Elwell Law in 1968, recognizing that acquiring park land should be a citywide responsibility, not dependent on a neighborhood’s willingness or ability to pay.

I have presented some examples of park acquisition issues that aren’t as simple as “racist or not” and don’t fit the narrative some researchers have created from Mapping Prejudice data. Those narratives contain little if any evidence to support claims that the park board participated actively or even passively in creating “whites-only” neighborhoods or favoring them with parks. There is neither correlation nor causation to support claims of collusion. I find it impossible to discern a racist pattern in park board acquisitions during the racial covenant years.

It is also quite clear that racist behaviors limited where Black people could live during those years. “Stories” on the Mapping Prejudice website provides some examples, and I have read others, of individuals encountering viciously discriminatory behavior in neighborhoods across the city with or without racial covenants. (See especially Eric Roper’s “Ghost of a Chance” podcast.) Even Bob Williams, the first Black player for the Minneapolis Lakers in 1955 encountered hostility when he bought a house on Clinton Avenue in South Minneapolis, although initial reactions cooled when neighbors learned from the cover story in the Picture magazine of Minneapolis Sunday Tribune that he was an NBA player.)

People should be held to account for racist and bigoted behavior, for a failure to treat people fairly and respectfully as individuals. That goal is not achieved by making unsupported generalized claims that merely suppose people’s motivations — past, present, or future — or convict them of the crimes of others.

I have had the good fortune to have lived and traveled extensively in other countries and I often encountered people who had firm opinions of the United States and Americans. I know if I were abroad now, I would face questions about present US government policies on several fronts. I would protest that I disagree strenuously with many current policies and I would be met at times with a shrug, “Well, it’s your country.” That’s a broad brush I would not want to be painted with. Would those who stretch the data from a worthwhile project like Mapping Prejudice to the breaking point judge me guilty anyway?

David Carpentier Smith

Forfeited Land, Creative Additions

I recently received a note from Etch Andrajack about his fond memories of growing up near Hi-View Park in Northeast Minneapolis and what an important part the park played in the lives of his family and friends. His note prompted me to revisit the history tab on the Park Board’s page about Hi-View Park at minneapolisparks.org. (Every park has a history tab. I wrote most of them in 2008, but they are updated by park board staff as new developments warrant.)

In reviewing Hi-View’s history I was reminded of a tool the park board used to create or expand several recreation parks that are likely remembered as fondly as Etch remembers Hi-View. Landowners who don’t pay their property taxes eventually may forfeit their land. That land can be sold by the state or managed for “public benefit.” The Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners, as the Park Board was once officially called, acquired the land for Hi-View Park–free–under the public benefit provisions. I’ve cited below a section of the history of Hi-View Park, which I wrote for the park board’s website, that mentions other park land acquired through tax forfeiture.

“Hi-View Park was acquired from the state in 1950. The state had acquired the property for non-payment of property taxes. The original park was 3.74 acres, but was expanded by 0.12 acres in 1961 at a cost of $4,900. The park board acquired the land at a time when it was looking to fill gaps in playgrounds identified in a 1944 study of park facilities. While the neighborhood around Hi-View was not on the list of neighborhoods needing playgrounds, the park board seized the opportunity to obtain free land from the state, when it discovered the land was on the state’s list of tax-forfeited properties. The undeveloped land had been used as a playing field by children in the neighborhood for years.

The first instances of the park board seeking land on state tax-forfeiture lists was in 1905 when it acquired several lots to expand Glenwood (Wirth) Park and in 1914, when it acquired Russell Triangle. With the acquisition of four lots to enlarge Peavey Park and the acquisition of Northeast Field partly from the state’s tax forfeiture list in 1941, the park board began looking to the state as a source of cheap land.

In a matter of a few years after World War II, the park board acquired nearly all of Bossen and Perkins Hill parks and portions of McRae and Kenny from the state for no cost. The park board also eventually acquired part of North Mississippi Park from the state. By the late 1940s, the park board routinely scanned lists of land the state had acquired for non-payment of taxes and spotted the Hi-View land on such a list.”

I mention the acquisition of tax-forfeited land because it underscores the many creative methods used to acquire the land that became a celebrated and heavily used park system. Some parks are used primarily by neighborhood kids, others by people from across the entire city, state and beyond.

The park system is the result, in the end, of dedicated, persistent, efficient, and creative public servants. And it is still operated, managed, and adapted to our ever-changing needs and desires by the same type of praise-worthy public servants to whom we all owe a debt of gratitude. At the very least some respect.

David C. Smith

Lake Hiawatha Water Management

The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board (MPRB) recently published background documents on water management issues at Lake Hiawatha and Hiawatha Golf Course that have guided priority-setting and decison-making for the past two years. I would encourage everyone with an interest in the subject to have a look at the papers in the “What’s New” tab at the bottom of the linked page. For many of those most involved in the issue, this review of the project may be redundant, but for many others it will establish a useful starting point for discussion. Even for experts, these documents may provide a good review of the analysis and evaluations upon which park board staff have relied.

What I have not found in those otherwise useful briefings was a recap of historical events to put water levels in perspective. So….here goes. Let’s turn the clock back again. (For more background on the creation of Lake Hiawatha and the adjacent Hiawatha Golf Course and some cool “before” photos, read my recent post Troublesome Lake Hiawatha.)

Lake Depth

Theodore Wirth’s initial plan for dredging Lake Hiawatha was to dredge to a depth of 14 feet. Due to budget concerns, however, he had reduced his dredging plan to a depth of ten feet when contracts were let. In his 1929 annual report (dated January 1, 1930), he wrote that ten feet “as called for in the present contract is the very minimum depth a lake should be, and the only reason for specifying such a minimum depth was to keep the cost…down.” He added, however, that due to money saved through a very competitive bidding process, “it is my earnest recommendation that it be increased to fourteen feet.” His argument was twofold: one, it would produce a “cleaner” sheet of water with less vegetation; two, it would bring the land area to a “higher and more desirable grade at a reasonable cost of $35,000.” That additional four feet of dredging, he noted the next year, had produced an additional 270,000 cubic yards of material.

By the time grading of the new golf course was done, Wirth wrote in his 1932 report that a low lake level and favorable weather had “permitted the creation of much more undulation than hoped for in the great area of level land devoted to the golf course…with the happy result that the eighteen holes will be a more interesting course than it was anticipated could be made.” Had more extensive grading also produced more low areas that could eventually flood?

Lake Level

The lake level used as the average in the contemporary water management study reached via the link at the top of this post is 812.8 ft MSL or above mean sea level. The measurement of levels has changed a few times in the last century. The water levels cited in park board reports from its beginning in 1883 through the time Lake Hiawatha was dredged were in feet above “city datum.” Never mind what that means for a moment. In his 1931 annual report Wirth gives a “normal” elevation of Lake Hiawatha as 100 city datum. To translate city datum measures to contemporary MSL measures requires the addition of roughly 710 ft to the city datum. (If a geodesist finds that I’m off, please let me know a better translation.)

Yikes! That means today’s “normal” of 812.8 ft. MSL is nearly three feet above normal in Wirth’s time of about 810 ft MSL. Take three feet of water off Lake Hiawatha today and most of the golf course and all surrounding neighborhood basements are dry.

But wait, there’s more!

Although 100 was considered the normal level for Lake Hiawatha in 1931 the actual water level that year—the year dredging was finished in a very dry year—was only 96.25! In today’s terms that would be about 806.25 ft MSL, or six-and-a-half feet, roughly one Kawhi Leonard, below today’s normal!

Wirth provided this data in a section of his 1932 report that explained how the park board had contracted with the city to pump city water into the lakes to raise levels. In 1931 the park board paid the city $1,422.25 to pump 113,780,090 gallons of city water into Lake Hiawatha to raise its level to 98.62 ft or roughly 208.62 ft MSL, still four feet below today’s normal! The same year the park board paid the city $3,071.09 to pump 245,687,400 gallons into the Chain of Lakes (Cedar, Isles and Calhoun) and $1,201.19 to pump 96,095,580 gallons into Nokomis.

Why did they do it? Wirth’s words:

“As an experiment to find out definitely how practical and at what cost it would be feasible to raise our lake levels during dry periods, and in order to have the appearance of our lakes in presentable condition for the Knights Templar Conclave in June, together with a desire to have the bathing beaches at certain lakes made available for use…It will be difficult to operate our Lake Calhoun and Lake Nokomis bath houses efficiently with the present elevation of water.”

While noting that given the board’s finances it would be difficult to find the funds to pump water into the lakes in 1933, the Great Depression was grinding people and landscapes to dust, Wirth estimated it would cost $21,762.50 to pump the 1.741 billion gallons of water needed to raise the lakes to normal elevations. (Precision was one of Wirth’s strong suits—as was his compulsion to make his parks “presentable”.) That money was not forthcoming from the park board’s budget, and that year the situation was the “worst in memory,” Wirth wrote. But water was pumped thanks to the city council which had “come to the rescue”.

Not the End

That beneficence was not, of course, the end of water level problems in Minneapolis lakes. By the mid-1950s the situation was so bad that a pipeline was built from Bassett’s Creek to Brownie Lake to pump water into the lakes and ultimately Minnehaha Creek. Unlike Minnehaha Creek, Bassett’s Creek seldom went completely dry. Even that wasn’t a long-term solution. The park board considered a famous hydrologist’s recommendation in the 1960s to capture water from the air conditioners of downtown office buildings to recycle through the lakes. But the owners of those buildings knew a good idea when they heard one and began recycling their air conditioning water back through their own plants. So the park board eventually built a pipeline from the Mississippi River to the lakes, but that failed too when high phosphate levels in river water threatened lake health. So as you can see, through most of park board history the big challenge was how to raise lake levels, not lower them.

Despite the park board’s ownership of the land fronting on lakes and creeks—one of the marvels of the city—we should keep in mind that the park board cannot manage water tables. Has the park board altered shore lines and creek beds? Absolutely. And anytime that is done there can be unintended consequences that can play out over many years. (“Don’t mess with Mother Nature,” some would say! I am presently writing about one of those decisions that still could have very sad consequences.) But water tables, precipitation and run-off (climate change!) are not within the park board’s control—even when, as at present, park commissioners envision a role for the park board in issues outside the purview of historical park and recreation management. And although I am not a hydrologist, it does not seem logical to me that past park board water-shaping efforts—short of building dams, which they did not do except at Longfellow Lakelet and Shingle Creek—could have been the cause of higher water tables across a wide section of the city.

In my opinion, informed by what I know of the history of the area, the groundwater issue is one for which the park board should not take primary responsibility. I think it demands a broader solution that the city or county and state should address—with input from the park board as a significant stakeholder. Just because the easiest place to dump water from south Minneapolis is into property controlled by the park board (Lake Hiawatha) does not make excess water the park board’s unique problem.

The larger issue in this as in so many issues we wrestle with today is the relative weight of individual interests and collective interests. Striking that balance has always been at the core of the American Experiment. Pursuing that line of thinking, I checked when some of the houses now threatened by high water levels were built. Of all those houses that were actually surveyed for the water management study conducted in 2017 for the park board, only one of 28 was built after 1954 according to Hennepin County property records. Nearly half were built before 1932 when the park board finished dredging Lake Hiawatha. In other words, they were built when water levels did not seem to pose a threat.

I hope you will take a closer look at the background information posted by the park board at minneapolisparks.org. I would also encourage you to subscribe to email updates from the park board on the status of plans for Lake Hiawatha and other park areas of interest.

David Carpentier Smith

Closing Parkways: Not a New Idea, or a Good One

The Minneapolis Park Board considered chopping up the Grand Rounds once before. That proposal was rejected, as I hope this one will be.

On May 30, the park board published a draft of its “preferred concept” for the Minnehaha Parkway Regional Trail from where Minnehaha Creek enters Minneapolis from Edina, east to Hiawatha Avenue near Minnehaha Park. I would encourage everyone to review the draft concept, especially page 7 of the linked document, which addresses “Parkway Vehicluar Circulation.” I believe that is where the plan fails, because it proposes to place roadblocks at some intersections that will force cars to leave the parkway, which creates in essence more “missing links” in the Grand Rounds. It will essentially end the practice of driving Minnehaha Parkway for pleasure. Continue reading

G’day Maka Ska, G’bye Calhoun?

Efforts to eradicate the name Lake Calhoun and replace it with Bde Maka Ska have generated a great deal of discussion and passion on many sides. The usage of the recommended new name and its meaning and pronunciation have been badly muddled, however, which confuses the issues unnecessarily.

Let me, a non-Dakota speaker, try to clarify. Bde Maka Ska is one of the Dakota names for the lake that was named Lake Calhoun by white surveyors or soldiers sometime before 1820. We have been told often that the term translates as White Earth Lake. So far, so good. But let’s break it down further.

Translation

Bde: lake

Maka: earth

Ska: whitePronunciation

Bde: The “e”, as in Spanish, is more like “ay” as in day. Hear Crocodile Dundee saying “G’day, mate.” Say b’day like an Australian caricature says “g’day” — rather than b-day which suggests a pronunciation more like a fixture in a French bathroom. G’day. B’day. Closer to one syllable than two.

Makaska: I’ve cheated and put the two words together, which to my ear is how Dakota speakers pronounce them. All a’s are pronounced as in “Ma” for mother. Accent the middle syllable, as if you were saying “my Costco.” MaCostco. Makaska.

This is the easy part and should not have any bearing on the merits of changing the name. It’s not hard to say, so let’s not use that excuse. How do you know how to pronounce “Isles” in “Lake of the Isles” with two of five letters silent? You learned — and thought nothing of it. Not difficult.

Usage

This is a little trickier. I don’t know Dakota patterns of usage, but to my view the Minneapolis park board’s master plan entitled Calhoun/Bde Maka Ska-Harriet, which recommended the name change, is confusing. If we are dropping “lake” from Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet, in this context shouldn’t we also drop “bde” from Bde Maka Ska. Otherwise it would be Lake Lake White Earth.

In other words, Bde Maka Ska replaces Lake Calhoun, not just Calhoun. Maybe Dakota grammarians would box your ears if you said the equivalent of, “I’m going to bike around Maka Ska this afternoon.” Maybe in Dakota “lake” or “bde” must always be part of a lake name. But if the “bde” doesn’t have to bde there, couldn’t the park board have approved renaming the lake “Maka Ska”? I ask in part because I haven’t heard any objection to the word “lake” itself, although Tony Lake, Lake Street, and Veronica Lake all have had detractors. (I’ve never seen her right eye!)

It matters because any use of Calhoun alone then is unaffected, which is a bit exasperating, because that’s the objectionable part. So on the parkway signs that say East (or West) Calhoun Parkway it was incorrect to add Bde Maka Ska, as was done last year. Only signs that say “Lake Calhoun” should have been changed. Even the vandals of signs at Lake Calhoun last year didn’t know what they were doing when they replaced only Calhoun, but not Lake, with Bde Maka Ska. Pretty ignorant activism.

I raise this issue primarily for clarification. We know some lakes around the world by their indigenous names, Loch Ness comes to mind, and others have retained names given by non-English speakers, such as Lac qui Parle in western Minnesota (not just a lake but a county), a French translation of the Dakota words “lake that speaks”. (Was “bde” part of that Dakota name?)

Something to Consider

So… how should we treat Bde Maka Ska? Wouldn’t it be easier to discuss the merits of a name change if we said we wanted to change the name from Lake Calhoun to Lake Maka Ska? Dakota and Ojibwe names for lakes and places abound in Minnesota and no one seems to have a problem with that. Yet I’ve never seen any other lake named Bde Anything. There are many a “mni” — Dakota for “water” — anglicized to Minnetonka, Minnesota, Minnehaha, but not a “bde” that I know of.

I suspect that some people opposed to renaming the lake get hung up on “bde” for “lake”. It’s a diversion from the real issues, which are, “Calhoun or not?” And, “If not, what?” Lake Maka Ska might eventually be adopted by those who don’t speak Dakota. Bde Maka Ska will take decades longer — if the bde isn’t dropped quickly anyway.

Where Does the Name Come From?

Knowing a bit of the history of Lake Calhoun since 1820, I’m also curious how the lake got the name “White Earth”. We know that parts of the shoreline, especially on the south and west, were quite marshy by the mid- to late-1800s and had to be filled eventually to hold parkways. But we also know from dredging reports that the beach on the north side at the site of the bath house built in 1912 was created or greatly augmented by considerable dredging from sand found on the lake bottom.

Lake Calhoun’s northwest shore and Bath House in late 1910s, before a parkway existed on the west side of the lake, although there is a light-colored trail or path. The north beach was mostly man-made. Photo likely taken from near the Minikahda Club. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

To my knowledge the dredging at Lake of the Isles and Cedar Lake produced little sand from those lake bottoms. Lake Harriet has never been dredged. It’s not obvious from any accounts I’ve seen of why “maka ska” or “white earth” was used to distinguish this lake from neighboring lakes in Cloud Man’s time or earlier.

Maybe a geologist could enlighten me. Were there relatively white deposits of sand in the vicinity at some point? What is the geological explanation? (For those of us who still believe in science anyway.) Were the shores of Lake Calhoun once sandy — before beaches, parkways and retaining walls?

If anyone can enlighten us about the Dakota language or can explain the park board’s garbled use of Bde Maka Ska, sometimes as a substitute for Lake Calhoun and others for Calhoun only, or can tell us about “white earth”, please do. I won’t post comments on whether we should keep or erase the Calhoun name; many other venues provide space for those arguments.

David C. Smith

Defining Wirth

The Minneapolis Park Board and Hennepin County Library report that we are probably only weeks away from the transfer of the park board’s historical archives to the downtown Minneapolis library. A valuable trove of historical information will be preserved, protected and made available to the public as never before.

Theodore Wirth outside the house built by the park board at Lyndale Farmstead in 1910. This 1927 Christmas card was found in the park board files moved from the City Hall clock tower to park board headquarters to prepare them for their imminent transfer to the Hennepin County Library. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.)

Among the more intriguing documents discovered in preparing those archives for transfer to a better place was a letter from Theodore Wirth to Charles Loring, July 4, 1905, after Wirth visited Minneapolis to consider taking the position of Superintendent of Parks. Upon returning to his home in Hartford, Connecticut, where he held a similar position, Wirth wrote to thank Loring for his hospitality and, more importantly, to outline his terms for accepting the position in Minneapolis.

The letter was an exciting discovery because for many years I and others have looked for evidence that Loring and the park board had agreed in 1905 to build a house for Wirth. That house was eventually built in 1910, four years after Wirth came to Minneapolis, at Lyndale Farmstead on Bryant Avenue near Lake Harriet. Theodore Wirth lived in the house until 1945, ten years after he retired as park superintendent. It was occupied by succeeding superintendents from then until David Fisher moved out of the house to one of his own choosing in the mid-1990s. The house became the residence of the superintendent once again in 2010, however, when Jayne Miller chose to live there when she moved to Minneapolis.

The construction of a house on park property for Wirth was very controversial in 1910. The park board’s authority to build it was challenged in court. The park board justified its decision in part by claiming that the structure was not just a residence, but an administration building—and also claimed that the house fulfilled a condition of Wirth’s employment years earlier.

Although park board plans to build the house as a residence for Wirth survived a court challenge—by a split vote in the Minnesota Supreme Court—historians, including me, had found no proof that the park board had agreed to provide housing for Wirth. I had seen a copy of Wirth’s five-page letter from 1905 proposing the terms of his employment, but the pertinent portions of that copy were utterly illegible. Now, we can read them in Wirth’s original ink.

In his July 4, 1905 letter Wirth wrote that among his conditions for accepting the park superintendent’s job in Minneapolis, “I would expect that as soon as circumstances permit I be furnished a house and privileges similar to what I am having now.” As superintendent of parks in Hartford, Connecticut, Wirth and his family lived on the second floor of a large house that stood on land donated as a park to Hartford. The ground floor of that house served as a concession stand and visitors center. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

In a subsequent letter to Loring, Wirth wrote that while he was torn between staying in Hartford or moving to Minneapolis, he had stated his terms for accepting the Minneapolis job and the park board had agreed to them, so he felt honor-bound to accept the new job. That is as close as we can get, without seeing Loring’s actual response to Wirth, to knowing that Loring and the park board had agreed to meet Wirth’s expectation of a house.

Why had the original letter been missing for so long? We found it in a file of park board correspondence not from 1905, but 1911! No one ever would have looked for it there. I suspect it was filed there after the court case had been decided and the supporting documents were no longer needed and were thrown into a current file. It probably hadn’t been looked at between 1911 and last summer.

Proper Attribution: A Park within a Half-mile of Every Residence?

Another discovery of interest to me in the documents soon to take up permanent residence at the library was a memorandum from Wirth that sheds light on the often-repeated claim that he championed a playground within a half-mile of every residence in the city.

The attribution of that claim to Wirth often presumes that he not only supported it but that it originated with him. I have scoured Wirth’s writing and the park board’s published records for the source of that particular measure for playground location. No luck. I couldn’t find that standard proposed by Wirth even in the hundreds of pages he wrote for his annual reports.

The only similar claim I was able to find was in the autobiography of Wirth’s son Conrad, who was the director of the National Park Service 1951-1964. In Parks, Politics and the People, published in 1980, more than 30 years after his father’s death, Conrad associated the “park within a half mile” concept with his father.

Then came the deep dive into once dusty archive boxes. A 1916 committee file contained many petitions signed by residents of south Minneapolis asking for a park at 39th and Chicago — what eventually became Phelps Field. Theodore Wirth submitted his opinion to a joint committee considering the issue. He opposed the playground because it was within the district already served by Nicollet (Martin Luther King) Field and Powderhorn Park. He explained,

“It is conceded by playground authorities from all parts of the country that one good-sized playground per square mile of city area is sufficient for even densely populated districts.”

That hardly seems the statement of a man who had created the standard. While I have not researched the subject on a national scale to see where the standard did originate, it appears that the park per square mile standard was already widely used. Keep in mind that Minneapolis was fairly late to the practice of establishing playgrounds under the auspices of a park board, so it was an unlikely pioneer in developing standards for playground locations. To the credit of Minneapolis and Theodore Wirth, however, Minneapolis probably came closer to meeting that standard eventually than almost all other cities.

By the way, the park board did not take Wirth’s advice in this instance and approved the acquisition of Phelps Field despite its proximity to other playgrounds and the large amount of grading that Wirth asserted would be required to make the land into usable playground space.

Hundreds more documents, like these, that provide information and insights into the creation and evolution of Minneapolis’s parks will soon be available to everyone at the library.

Congratulations!

The transfer of the park board archives culminates the work of several years. Park commissioners, led by Scott Vreeland, superintendent Jayne Miller, and park board staff, especially Dawn Sommers and former real estate attorney Renay Leone, deserve thanks for their commitment to preserving park historical records. The project also owes a great deal to the cooperation of Josh Schaffer in the City Clerk’s office, and Ted Hathaway, director of Special Collections at Hennepin County Library.

I would encourage local historians, especially those with an interest in the first half of the 20th Century, as well as park enthusiasts, to take a look at the archives once Ted and his staff at the library can make them available. They provide a fascinating historical view of not just a park system, but a city.

David C. Smith

100 Years Ago: Altered Electoral Map and Shorelines

What has changed in 100 years? A few times on this site, I have looked back 100 years at park history. I’ll expand my scope this year because of extraordinary political developments. Politics first, then parks.

The national electoral map flipped. The electoral map of the 1916 Presidential contest is astonishing. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, won a close re-election against Republican candidate Charles Hughes, a Supreme Court Justice. Compare red and blue states below to today. Nearly inverted. The Northeast, Upper Midwest and Far West — well, Oregon — voted alike. Republican. And lost.

The 1916 electoral map was nearly opposite of the 2016 electoral map in terms of party preference. Unlike 2016, President Wilson won both the popular vote and the electoral vote, but his electoral-vote margin was smaller than Donald Trump’s. If the total of votes cast in 1916, fewer than 19 million, seems impossibly low even for the population at that time, keep in mind that only men could vote. (Source: Wikipedia)

While Minnesota’s electoral votes were cast for the Republican — although Hughes received only 392 more votes than Wilson out of nearly 400,000 cast — Minneapolis elected Thomas Van Lear as its mayor, the only Socialist to hold that office in city history. One hundred years later, Minneapolis politics are again dominated by left-of-center politicians.

The population of Minneapolis in 1916 and 2016 was about the same: now a little over 400,000, then a little under. Minneapolis population peaked in mid-500,000s in mid-1950s and dropped into mid-300,000s in late 20th Century. One hundred years ago, however, Minneapolis suburbs were very sparsely populated.

The world 100 years ago was a violent and unstable place. World War I was in its bloody, muddy depths, although the U.S. had not yet entered the war, and Russia was on the verge of revolution. Now people are killed indiscriminately by trucks, guns, and bombs. People worldwide debated then how to address the excesses of capitalists, oligarchs and despots unencumbered by morality. We still do.

One notable change? Many Americans campaigned in 1916 to put women in voting booths, in 2016 to put a woman in the Oval Office.

Continuing Park Growth: North and South

How about progress in parks? The Minneapolis park board added significantly to its playground holdings in 1916 and 1917 as public demand for facilities and fields for active recreation increased. In North Minneapolis, Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park was expanded and land for Folwell Park was acquired. In South Minneapolis, Nicollet (Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.) Park and Chicago Avenue (Phelps) Park were purchased and land for Cedar Avenue Park was donated. In 1917, the first Longfellow Field was sold to Minneapolis Steel and steps were initiated to replace it at its present location.

One particular recreational activity was in park headlines in 1916 for the very first time. A nine-hole course was opened that year at Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park, the first public golf course in Minneapolis. Golf was free and greens weren’t green, they were made of sand. In less than ten years, the park board operated four 18-hole courses (Glenwood [Wirth], Columbia, Armour [Gross], and Meadowbrook) and was preparing to add a fifth at Lake Hiawatha.

The Grand Rounds were nearly completed conceptually, when first plans for St. Anthony Boulevard from Camden Bridge on the Mississippi River to the Ramsey County line on East Hennepin Avenue were presented in 1916. Park Superintendent Theodore Wirth also suggested that the banks of the Mississippi River above St. Anthony Falls might be made more attractive with shore parks and plantings, even if the railroads maintained ownership of the land. One hundred years later we’re still working on that, but have made some progress including the continuing purchase by the Park Board of riverfront lots as they have become available.These have been the only notable additions to park acreage in many years.

One important result of the increasing demand for playground space in Minneapolis one hundred years ago was the passage by the Minnesota legislature in 1917 of a bill that enabled the park board to increase property tax collections by 50%. In 2016, the Park Board and the City Council reached an important agreement on funding to maintain and improve neighborhood parks.

Altered Shorelines

In a city blessed with water and public waterfronts, however, some of the most significant issues facing the Minneapolis park board in 1917 involved shorelines — beyond beautifying polluted river banks.

The most contentious issue was an extension of Lake Calhoun, a South Bay, south on Xerxes Avenue to 43rd Street. Residents of southwest Minneapolis wanted that marshy area either filled or dredged — dry land or lake. There was no parkway at that time around the west and south shore of Lake Calhoun from Lake Street and Dean Parkway to William Berry Parkway. As a part of plans to construct a parkway along that shoreline, the park board in 1916 approved extending Lake Calhoun and putting a drive around a new South Bay as well.

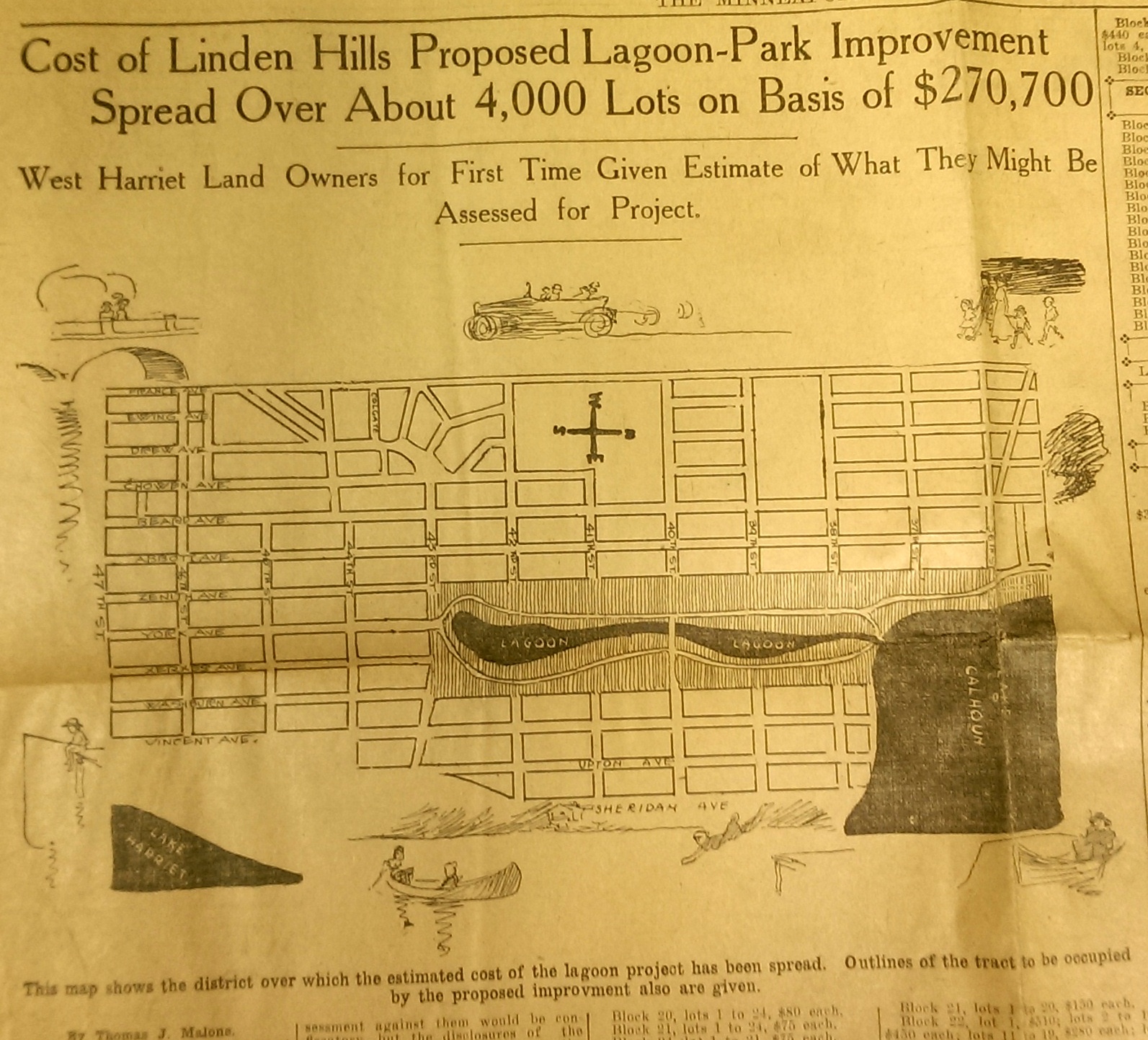

This drawing from a 1915 newspaper article shows the initial concept of a South Bay and outlines how it would be paid for. (Source: Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, June 20, 1915)

The challenge, of course was how to pay for it. The park board’s plan to assess property owners in the area for the expensive improvements was met with furiuos opposition and lawsuits. Many property owners thought that assessments they were already paying for acquisitions and improvements over the years at Lake Calhoun, Lake Harriet and William Berry Park were too heavy. The courts eventually decided in favor of the park board’s right to assess for those improvements, but by then estimated costs for the project had increased and become prohibitive and the South Bay scheme was abandoned.

Instead land for Linden Hills Park was acquired in 1919 and the surrounding wet land was drained into Lake Calhoun in the early 1920s. Dredged material from the lake was used to create a better-defined shoreline on the southwestern and northwestern shores of the lake in 1923 in preparation for the construction of the parkway.

Flowage Rights on the Mississippi River and a Canal to Brownie Lake

Minneapolis parks also lost land to water in 1916. The federal government claimed 27.6 acres of land in the Mississippi River gorge for flowage rights for the reservoir that would be created by a new dam to be built near Minnehaha Creek. Those acres, on the banks of the river and several islands in the river, would be submerged behind what became Lock and Dam No. 1 or the Ford Dam. In exchange for the land to be flooded, the park board did acquire some additional land on the bluffs overlooking the dam.

The other alteration in water courses was the dredging of a navigable channel between Cedar Lake and Brownie Lake, which completed the “linking of the lakes” that was begun with the connection of Lake of the Isles and Lake Calhoun in 1911. The land lost to the channel was negligible and probably balanced by a slight drop in water level in Brownie Lake. (A five-foot drop in Cedar Lake was caused by the opening of the Kenilworth Lagoon to Lake of the Isles in 1913.)

Another potential loss of water from Minneapolis parks may have occurred in 1917. William Washburn’s Fair Oaks estate at one time had a pond. I don’t know when that pond was filled. The estate became park board property upon the death of Mrs. Washburn in 1915. Perhaps in 1917 when the stables and greenhouses on the southwest corner of the property were demolished, the south end of the estate was graded and the pond was filled. Theodore Wirth’s suggestion for the park, presented in 1917, included an amphitheater in part of the park where the pond had once been.

The Dredge Report

The year 1917 marked the end of the most ambitious dredging project in Minneapolis parks — in fact the biggest single project ever undertaken by the park board until then, according to Theodore Wirth. The four-year project moved more than 2.5 million cubic yards of earth and reduced the lake from 300 shallow acres to 200 acres with a uniform depth of 15 feet.

That wasn’t the end of work at Lake Nokomis, however. The park surrounding the lake, especially the playing fields northwest of the lake couldn’t be graded for another five years, after the dredge fill had settled.

Dredging may again be an issue in 2017 if the Park Board succeeds in raising funds for a new park on the river in northeast Minneapolis. Dredges would carve a new island out of land where an old man-made island once existed next to the Plymouth Avenue Bridge. But that may be a long time off — and could go the way of South Bay.

Park Buzz

One other development in 1917 had more to do with standing water than was probably understood at the time. The Park Board joined with the Real Estate Board in a war on mosquitoes. However, after spending $100 on the project and realizing they would have to spend considerably more to achieve results, park commissioners terminated the project. It was not the first or last battle won by mosquitoes in Minneapolis.

As we look again at new calendars, it’s always worth taking a glance backward to see how we got here. For me, it is much easier to follow the course of events in Minneapolis park history than in American political history.

David C. Smith

Comments: I am not interested in comments of a partisan political nature here, so save those for your favorite political sites.

Defending Minneapolis Parks

For decades, public and private parties have claimed that they need just a little bit of Minneapolis parkland to achieve their goals. And now even Governor Dayton has joined the shrill chorus of those who think taking parkland is the most expedient solution to political challenges. The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board (MPRB) is justified in examining very skeptically all desires to take parkland for other purposes and in rejecting nearly all of them categorically.

Commentators writing in December in the StarTribune asserted that the Park Board is wrong to object to just 28 feet of bridge expansion over Kenilworth Lagoon for the construction of the Southwest Light Rail Transit (SWLRT) corridor. They write as if that bridge and expansion of rail traffic across park property were the only alternative. Gov. Dayton seems to repeat the error. Other political jurisdictions involved in the proposed light rail corridor have objected to this or that provision of the project and their objections have been given a hearing, often favorable.

I didn’t hear Governor Dayton threaten to slash local government aid to St. Louis Park when officials there objected to the Met Council’s original proposals for SWLRT. But the Park Board is supposed to cave into whatever demands remain after everyone else has whined and won. Minneapolis parks are too valuable an asset – for the entire state – to have them viewed as simply the least painful political sacrifice.

Should the SWLRT bridge be built? I don’t know—but I do want the Park Board to ensure that all options have been investigated fully. That desire to consider all feasible options to taking parkland for transportation projects that use federal funds was first expressed in 1960s legislation. The legislation was meant to ensure that parkland would be taken for the nation’s burgeoning freeway system only as a last resort. In the present case, the Park Board was not convinced that the Met Council had investigated all options thoroughly once it had acquiesced to the demands of other interested parties.

A Park Board study in 1960 identified more than 300 acres of Minneapolis parkland that were desired by other entities both private and public. Hennepin County wanted to turn Victory Memorial Drive into the new County Highway 169. A few years later, the Minnesota Department of Highways planned to convert Hiawatha Avenue, Highway 55, into an elevated expressway within yards of Minnehaha Falls—in addition to taking scores of acres of parkland for I-94 and I-35W. In the freeway-building years, parkland was lost in every part of the city: at Loring Park, The Parade, Riverside Park, Murphy Square, Luxton Park, Martin Luther King Park (then Nicollet Park), Perkins Hill, North Mississippi, Theodore Wirth Park and others, not to mention the extinction of Elwell Park and Wilson Park. Chute Square was penciled in to become a parking lot.

In 1966, faced with another assault—a parking garage under Elliot Park—Park Superintendent Robert Ruhe, backed by Park Board President Richard Erdall and Attorney Edward Gearty, urged a new policy for dealing with demands for parkland for other uses. It was blunt, reading in part,

“Those who seek parklands for their own particular ends must look elsewhere to satiate their land hunger. Minneapolis parklands should not be looked upon as land banks upon which others may draw.”

With that policy in place, the Park Board resisted efforts by the Minnesota Department of Highways to take parkland for freeways or, as a last resort, pay next to nothing for it. Still, the Park Board battled the state all the way to the United States Supreme Court over plans to build an elevated freeway within view of Minnehaha Falls—a plan supported by nearly every other elected body or officeholder in the city and state, including the Minneapolis City Council.

Robert Ruhe, middle, Minneapolis Superintendent of Parks 1966-1978 proposed a tough land policy to defend against the taking of parkland for freeways and other uses. In this 1968 photo he is accepting a gift of 60 tennis nets from General Mills. Before that time, nets were not provided on most city courts. Players had to bring their own. (MPRB)

The driving force behind the park board’s defense of its land was better known as a Minnesota legislator and President of the Minnesota Senate from 1977-1981. Ed Gearty, far right, was President of the Minneapolis Park Board in 1962 when he was elected to the Minnesota House of Representatives. He had to resign his park board seat, but was then hired by the park board as its attorney. He helped devise a pugnacious strategy that helped keep park losses to freeways as small as they were. This photo with other state lawmakers was taken in 1978. Gearty deserves credit along with Ruhe, counsel Ray Haik and park board Presidents Dick Erdall and Walter Carpenter for trying to keep Minneapolis parks intact as a park “system.”

While the Supreme Court chose not to hear the Minnehaha case, its decision in a related case involving parkland in Memphis, Tenn. established a precedent that forced Minnesota to reconsider its Highway 55 plans and provides the basis for the Park Board today to investigate alternatives to taking park property for projects that use federal funds.

The Park Board is right to do so, even at the high cost it must pay—which the Met Council should be paying—and regardless of the results of that investigation. The Park Board needs to reassert very forcefully that taking parkland is a very serious matter and not the easiest way out when other arrangements don’t fall into place.

In a report to park commissioners on a proposed new land policy on April 1, 1966 Robert Ruhe concluded with these words,

“The park lands of Minneapolis are an integral part of our heritage and natural resources and, as such, should be available to all present and future generations of Minneapolitans. This is our public trust and responsibility.”

That trust and responsibility has not changed in the intervening 50 years. And it is not exercised well if the Park Board allows land to be lopped away from parks—even 28 feet at a time—without the most intense scrutiny and, when necessary, resistance. It could help us avoid horrors like elevated freeways near our most famous landmarks.

What I find most troubling about events of the past year relating to Minneapolis parks is the blatant disregard by elected officials—from Minneapolis’s Mayors to Minnesota’s Governor—of the demands and complexity of park planning and administration, as if great parks and park systems happen by accident. They don’t. They take conscientious, informed planning, funding, programming and maintaining. We can’t just write them into and out of existence as mere bargaining chips in some grander game. Parks should not be an afterthought in the crush of city or state business.

I worry when an outgoing mayor negotiates an awful agreement for a “public” park for the benefit of the Minnesota Vikings without the input of the people who would have to build and run it. I wince when an incoming mayor trumpets a youth initiative without input from the organization that has the greatest capacity for interaction with the city’s young people. And I am really perplexed when a governor makes so little effort to engage an elected body with as important a stake in a major project as the park board’s in the SWLRT.

Other elected officials seem more than happy to rub shoulders with park commissioners and staff when the Minneapolis park system receives national awards, or a President highlights the parks on a visit, or when exciting new park projects are unveiled. But they seem to forget who those people are when they are sending out invitations to the table to decide the city’s future. That is a serious and easily avoidable mistake.

David C. Smith

© 2015 David C. Smith

1911 Minneapolis Civic Celebration: Junk Mail

I have neglected these pages in recent months, yet I have so many good park stories to tell, some of them from readers. I will get to them soon I hope. In the last eight months I have discovered more fascinating information about Minneapolis parks and the people who created them than at any time since my initial research for City of Parks. But until I can get to those stories, I wanted to show you one of the more interesting bits of history I’ve encountered recently. Garish, but oddly charming.